Brexit and rules of origin: Why free trade agreements ≠ free trade

Without an EU-UK customs union British exporters will face a new barrier to trade: rules of origin. No amount of positive thinking and innovative solutions can eliminate this problem.

Where is the phone in your hand actually from? Designed in California, assembled in China, it says. But what about the components: the battery, the screen, the processor? Modern supply chains span continents – sometimes the globe – dipping in and out of countries as value is added along the way. The global factory, atomised among many locations, is mind-boggling to contemplate, it can also make it tricky to determine the provenance of any given product. This throws up a specific challenge for post-Brexit, ‘free-trading’ Britain: preferential rules of origin.

Because of rules of origin, even if the UK enters into a trade agreement with the EU, UK manufacturers embedded in pan-European supply chains are going to face new bureaucracy and costs, with long-run implications for their continued viability.

Rules of origin are one cost of #Brexit that no amount of positive thinking and innovative solutions can eliminate.

What are preferential rules of origin?

In brief, to benefit from the preferential tariff rates offered by a trade agreement, a UK exporter must prove that the product it is selling is actually from, or has had sufficient work done on it in the UK (subject to myriad terms and conditions). This is easy enough if the product is wholly obtained in the UK – for example, a cow – but it becomes more difficult if the product consists of inputs (components) sourced from all over.

For example, in order to sell a car to Korea tariff-free under the EU-Korea trade deal, an EU car exporter must demonstrate that over 55 per cent of the value of the car was created within the EU.

These preferential rules of origin exist to ensure that the product being sold under the terms of a free trade agreement is from one of the countries party to the agreement, and not, for example, from a Chinese firm exporting a widget to the EU via Vietnam (which will soon have a trade agreement in force with the EU) so as to avoid the EU tariffs normally levied on Chinese widgets.

The only way that the UK can remove the need for rules of origin is to remain in the EU customs union, or enter into a new one. If the UK remains committed to levying the EU’s external tariff on all goods entering from outside the customs union, then rules of origin do not become an issue because EU-level tariffs will have been paid on any components brought in from outside the Union. Without an EU-UK customs union, rules of origin create three immediate problems for post-Brexit Britain:

1) UK exporters selling a product to the EU27, under any free trade agreement, will be required to prove that the product they are selling is actually from the UK. Rules-of-origin-compliance can be costly. While a certificate of origin (usually certified by a UK Chamber of Commerce) only costs around £30 in the UK, the additional administration, legal and audit fees can be significantly higher. Estimates vary but have been put at between two and six per cent of product’s final value. If a false claim is made the exporter risks being sued by the importer.

These additional costs will reduce the competitiveness of UK exports to the EU vis-à-vis EU27-based producers. The additional border administration will also disrupt just-in-time supply chains, where even those who comply with ease will be held up by those who do not.

2) UK exports that incorporate a significant proportion of non-UK components may struggle to qualify as ‘British’ for a UK-EU free trade agreement. The rules for meeting the origin requirements of a free trade agreement vary sector-by-sector.

Sectors that traditionally find rules of origin burdensome include vehicles, textiles and some food and machinery. The requirements placed on chemicals can also be tricky to navigate. Mike Hawes, the CEO of The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, has said that there is a danger UK-built cars will not qualify under a normal free trade agreement: “Generally rules of origin require around 50 to 55 per cent local content. Currently in the UK, the average car has about 41 per cent local content.” In reality the UK originating content is even lower, with the 41 per cent encompassing all inputs bought from UK suppliers, which may have imported them from elsewhere.

Some sectors will be less affected (although they may still be required to produce non-preferential rules of origin declarations) because, thanks to specific WTO agreements, many products can be traded tariff-free regardless of any free trade deal. These include IT goods such as laptops; civil aircraft (although not all of the inputs); and some pharmaceutical products. Other exporters will have little difficulty claiming substantial work was done on the product in the UK due to easily demonstrable changes. For example: clay being moulded into a pot, or malted barley being distilled into Scotch whisky.

Chart 1 estimates the percentage of foreign inputs contained in UK exports. Of the sectors particularly vulnerable to rules of origin-based disruption, cars, chemicals and machinery are notably reliant on foreign inputs, with a significant proportion of those inputs originating from the EU-27.

3) UK exporters currently making use of EU free trade agreements with other countries may be used to complying with rules of origin. But they will face difficulties complying with existing rules if and when the UK replicates the EU’s free trade agreements with third countries post-Brexit. While currently ‘EU value-added’ counts as ‘local value-added’ for the purpose of qualifying for a given agreement, post-Brexit this will not necessarily be the case.

This may of course prove a problem for EU exporters as well. However, EU exporters are far less reliant on UK inputs than the reverse.

Even with a UK-EU trade agreement in place, rules of origin will lead to some UK exporters being less price-competitive in EU markets; choosing not to export at all; or, due to the complexity and/or cost of compliance not being greater than the potential tariff savings, choosing to export under WTO most favoured nation tariff rates. Exporters have under used trade agreements thanks to rules of origin (as well as failing to realise that a helpful trade agreement exists, in some cases). UNCTAD estimates that only two-thirds of EU exports are sold using the preferential tariff rates available under the EU’s trade agreements. EU exports are subject to additional tariff costs of around $79 billion as a result.

Damage limitation

Without a customs union, Brexit will inevitably impose new administrative costs on exporters. But there are policy options that could mitigate the damage.

As part of a new UK-EU free trade agreement, both parties could agree to allow for bilateral cumulation. This would allow exporters from the UK to consider EU inputs as being from the UK (and vice versa), allowing exports to meet the requirements of the agreement. This is a fairly common provision, found in existing EU free trade agreements such as EU-Korea and EU-Canada.

As demonstrated by Chart 2, this would make clearing any 50-60 per cent local value added threshold much easier.

This principle could, theoretically, be taken further to help UK exporters selling to existing EU FTA partners.

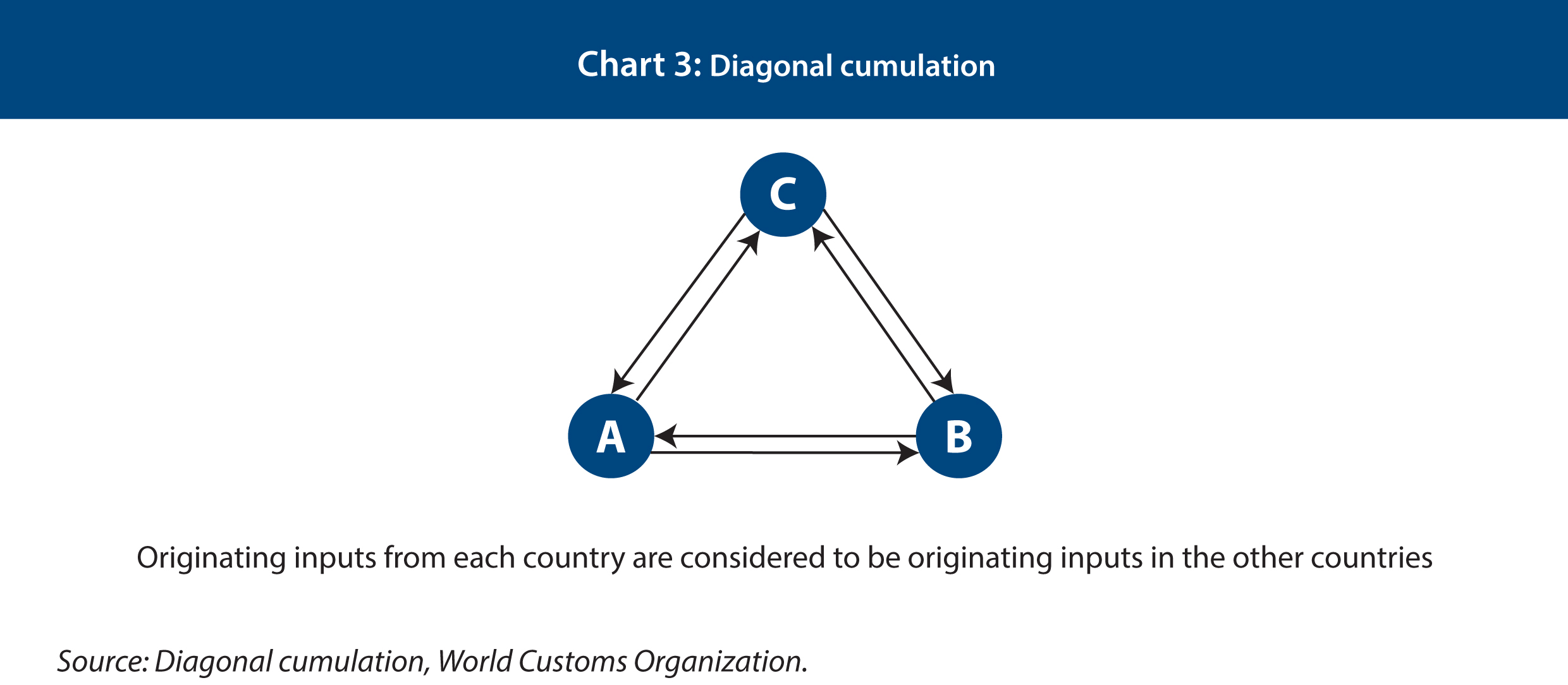

When (if) the UK replaces the existing EU free trade agreements, it could press for the EU, UK and the third country concerned to allow any input originating in one of the three parties to be ‘local’. This is called diagonal cumulation.

Diagonal cumulation is a solution that might help some exporters reliant on existing EU free trade agreements. But it’s not necessarily on the table.

There is in fact a ready-made treaty, called the Regional Convention on pan-Euro-Mediterranean preferential rules of origin (PEM convention), available to the UK allowing for diagonal cumulation with the EU and 22 other signatories (including Turkey, Israel, the EEA countries and Egypt). New EU free trade agreements such as EU-Japan have provisions allowing for the possibility if both the EU and Japan have a free trade agreement with the same partner. However, it is unlikely that the EU will rush into reopening negotiations with existing FTA partners in order to make life easier for the UK. Post-Brexit, if EU-based exporters do struggle to use EU FTAs due to UK content no longer qualifying it will ultimately lead to them buying components from businesses in the 27 instead.

The UK government has floated diagonal cumulation in the replaced EU free trade agreements, but without involving the EU. Under this approach, the UK would convince the FTA partner to continue to allow EU inputs to be treated as UK-originating, and leave it up to the EU whether they want to negotiate the reverse. However, such a concession will not come cheap. British officials have said that, in return, Korea is asking for Chinese inputs to its cars to be treated as though they were Korean. Such a concession would incense UK car makers.

The UK could also explore ways to reduce the compliance burden of rules of origin, for example by requiring 30 per cent local value added, rather than 55. Other measures could be taken to waive rules of origin on goods attracting a tariff of, say, below 5 per cent. This will, however, not be something Britain can decide unilaterally, and will require agreement from its FTA partners. Unfortunately for the UK, existing trends suggest qualifying requirements will get tougher rather than looser: Trump is pressing for higher thresholds in his renegotiation of NAFTA.

Ultimately, the impact of leaving a customs union is binary. Even retaining membership of the single market via the EEA agreement would not resolve the rules of origin problem (exports from Norway to the EU still have to prove origin). In the absence of a customs union, businesses exporting to the EU – many of whom have no experience exporting elsewhere – will face new administrative costs and bureaucracy. Assuming the UK manages to replace the EU’s FTAs, even those companies which now comply with the rules of origin will face new challenges proving that their products qualify. Steps can be taken to mitigate the damage, but rules of origin are one cost of Brexit that no amount of positive thinking and innovative solutions can eliminate.

Sam Lowe is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Add new comment