Dead or alive? A UK-US trade deal

The Chequers proposal would likely come at the cost of a transatlantic trade deal, but Theresa May is right to prioritise ties with the EU.

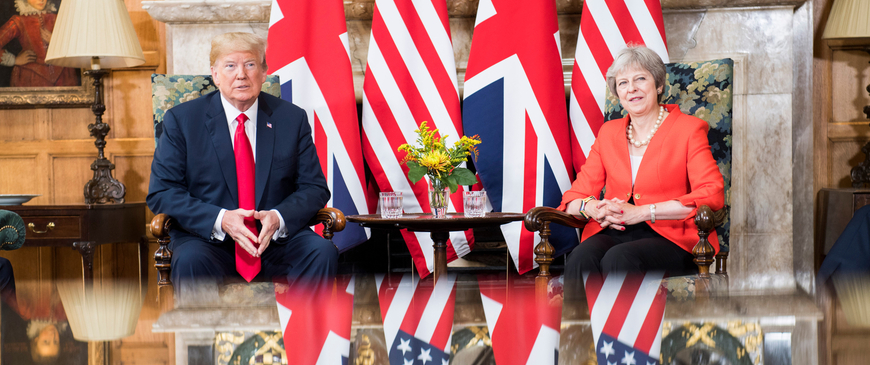

In his infamous interview with The Sun, US President Donald Trump warned that Theresa May’s Chequers plan would “kill” a trade deal with the US. He later backtracked, but the president was right the first time.

May’s proposal involves regulatory alignment with the EU on goods. Some EU rules conflict with America’s, making a trade deal with the US very difficult to conclude. However, it remains overwhelmingly in the UK’s economic interest to prioritise a close economic relationship with the EU over any potential trade deal with the US.

The promise of a UK-US trade agreement has political value, but no economic rationale.

The government’s recent white paper commits the UK to follow the EU’s rulebook on goods and food. Additionally, it would see the UK remain in a de facto customs union with the EU until new systems could be agreed. These systems would allow the UK to apply its own tariffs at the border, alongside the EU’s, depending on the final destination of an imported good. The prime minister hopes that such a partnership would obviate the need for additional infrastructure and checks at the EU-UK border (including the Irish land border), and secure British manufacturers’ position in pan-European supply chains.

But minimising trade barriers with the EU will come at a cost. The EU’s approach to goods standardisation and food and plant hygiene (SPS) has been frequently criticised by the US, most recently in its 2018 report on foreign trade barriers. The EU’s single standard model for goods is accused of unfairly discriminating against US and internationally recognised alternative product standards. European SPS rules effectively shut out American products like beef, chicken and pork, due to restrictions on the use of growth hormones and anti-microbial washes.

The EU’s SPS regime is particularly strict. If a country does not apply EU rules both domestically and in relation to third country imports, all of its exports of products of animal origin to the EU must enter through a veterinary border inspection post, where up to 50 per cent of containers are subject to physical inspections. If the UK were to accommodate American demands, the EU would be required to implement new checks on food imports from the UK, causing serious disruption for British suppliers currently selling, for example, Angus beef into the EU.

Furthermore, the US remains unconvinced that the EU will accept the UK’s ‘facilitated customs arrangement’, viewing it as a stalking horse for a permanent customs union, which would leave the UK unable to unilaterally lower its goods tariffs as part of a transatlantic trade agreement.

When caught in a tug of war between two regulatory superpowers, better the devil you know.

The UK faces a harsh dilemma. If it chooses to accommodate American demands as part of a transatlantic trade agreement, it will face a hard border with the EU and potentially on the island of Ireland, and disruption to trade.

The UK will attempt to square the circle. The white paper talks about gaining the flexibility to negotiate with third countries on issues such as mutual recognition of conformity assessment, which would allow a US-based certification body, for example, to confirm that a product produced in the US can be sold in the UK. The UK’s Department for International Trade has also had an internal discussion on a carve-out in Switzerland’s agreement with the EU, which allows the Swiss to import labelled hormone-grown beef from around the world on the condition that it is not forwarded to the EU market. However, the US is not interested in negotiating new agreements on mutual recognition of conformity assessment and the EU is unlikely to grant the UK the same flexibility as the Swiss. Even if it did, British farmers would be less sanguine about facing potential competition from cheaper US beef than the heavily protected Swiss agricultural sector.

The promise of a UK-US trade agreement has political value, but no economic rationale. It suits May to avoid acknowledging that the Chequers plan is incompatible with a US trade deal. Her Cabinet is split, and she cannot afford to incense hard-line Brexiteers, who view a US trade deal as the big prize of Brexit. The British government’s most optimistic estimate is that a UK-US trade agreement would boost the economy by just 0.3 per cent. But the type of Brexit needed to realise the gains of such a trade deal would leave the UK’s economy 4.8-7.8 per cent smaller than if it had remained inside the EU, according to the government’s own analysis.

May cannot afford to incense hard-line Brexiteers, who view a US trade deal as the big prize of Brexit.

It is unclear whether the EU-27 will accept May’s proposal, or whether it will survive the domestic political backlash. Dissent is currently raging through Parliament, and May has already been forced to make concessions to the hard-right of her party on the Customs Bill vote. But the prime minister was right to prioritise existing economic ties with the EU over much smaller future potential gains with the US. When caught in a tug of war between two regulatory superpowers, better the devil you know.

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow and Beth Oppenheim is a researcher at the Centre for European Reform.