How Greece can recover from Covid

- Greece has not been in the European spotlight since its economic and financial assistance programme ended in 2018, bringing eight years of economic crisis to a close. But the country still faces three major economic challenges over the coming decade.

- First, the scars of its long debt and economic crisis are still visible, with high unemployment on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, the loss of workers through a high rate of emigration and bad debt on banks’ books continuing to constrain lending.

- Second, the economic fallout of COVID-19 is adding to the hangover from the last crisis. While Greece managed the first wave well, its large tourism sector suffered severe losses.

- Third, the structural weaknesses that have held Greece’s growth back have not been resolved. While the country undertook heroic fiscal consolidation over the last decade, its reforms have not been as successful as hoped.

- The European recovery fund provides a unique opportunity to address some of the country’s challenges, such as its lack of sophisticated export industries, its failure to attract significant foreign investment, the paucity of financing for domestic entrepreneurs and its weak administration and judicial system.

- The national recovery and resilience plan that the Greek government has submitted to the EU contains many sensible proposals to deal with these problems. Its implementation will be tricky, but Greece may be about to turn a corner.

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit Greece hard. The Greek government was relatively successful in containing the first wave, but the tourism sector – which accounts for over 20 per cent of Greek GDP and is concentrated in the summer months – suffered from a steep fall in tourist arrivals from abroad. Domestic restrictions to contain the virus also took their toll. With a second wave underway that is hitting Greece harder than the first did, it is clear that the country will suffer huge economic damage from the pandemic. But there is hope. The arrival of multiple vaccines will probably end the pandemic in 2021. And with the EU recovery fund offering a unique opportunity for investment, Greece has the chance to tackle the obstacles that have held its growth back in the past. However, this will require bold policies and a laser-like focus on the most important reforms and investments.

Greece is facing three economic challenges over the next decade. The first is managing the economic fallout of the pandemic. The virus is hitting its economy hard because some activities, especially ‘social consumption’, such as restaurants and tourism, need to be restricted to contain the spread. The better the authorities keep infection rates low, and track and isolate infections that do occur, the stronger the economy. But some economic harm is unavoidable, and may well cause long-term scars: Greece’s economic potential will decline if businesses become too indebted or go bust, if banks sit on further bad loans, or if workers remain jobless for too long. Several vaccines are being distributed, but it will be late spring at least until the most vulnerable in society are vaccinated. The OECD reckons that Greece’s output contracted by 10 per cent in 2020, and that it will stagnate at a similar level for much of 2021 (that is a significant downgrade from previous forecasts, and quite pessimistic considering that the economy may bounce back strongly after vaccinations).1

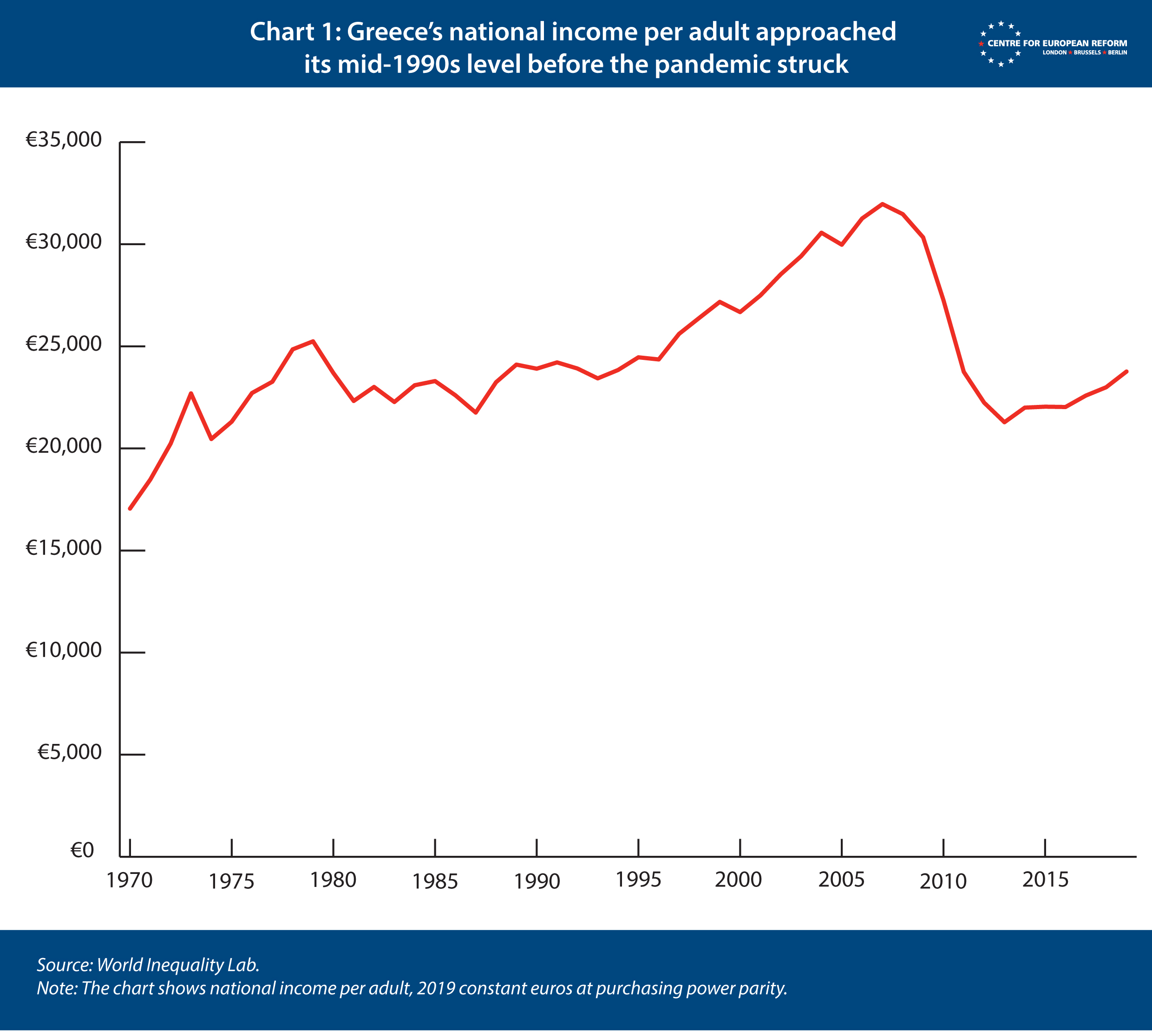

The second economic challenge, compounding the first, is that the scars of Greece’s decade-long economic crisis are still visible. Greece’s national income per adult was only creeping up to the levels of the mid-1990s at the end of 2019 (see Chart 1). Unemployment is still high: while the unemployment rate has fallen, it stood at 16 per cent on the eve of the pandemic, and an estimated 300,000 people (roughly 6 per cent of the labour force) have left the country for work or education. Moreover, another 300,000 are underemployed or have dropped out of the labour force altogether.

The Greek financial system was only slowly healing before the pandemic. The economic collapse of the 2010s left many homeowners with mortgages underwater and businesses in default. Before COVID-19 hit Europe, Greek banks still had around €65 billion (roughly 40 per cent of their loans) of ‘non-performing exposures’ on their books, such as loans in default or overdue on their interest payments. The impact of the pandemic on banks’ balance sheets can only be estimated, but so far, Greek banks have allowed borrowers to pause debt service on loans worth an additional €21 billion. The central bank of Greece estimates that around €9 billion of those loans will eventually turn sour.2

The third economic challenge is increasing the rate of economic growth. Greece undertook a heroic fiscal consolidation after 2010, and implemented some important reforms, under pressure from the ‘Troika’ of official lenders (see Box 1). But on measures of institutional quality, Greece still scores poorly. Measuring the quality of institutions is difficult, but the data does paint a consistent picture: registering property, enforcing contracts and getting access to finance, for example, is still very difficult.

Why has Greece not made more progress with its reforms? The first reason is practical. Implementing reform plans of such wide scope and depth requires capacity in the public administration. Modernising the judiciary, for example, is not a simple task of passing legislation, but requires many processes in courts to change. When problems with the implementation of reforms became apparent, the official creditors ended up micro-managing the process, with little success. Once the assistance programmes ended, the painful reform process stopped or went into reverse gear. There are only so many institutions and rules that a country can reform at the same time without being overwhelmed.

Second, to change the growth path of an economy, reforms need to be targeted at the crucial bottlenecks that are currently holding back growth and investment. Finding such bottlenecks is not easy. From the creditors’ perspective, the overarching problem was Greece’s high public debt and deficit. As a result, many reforms were fiscal in nature, to bring about the huge fiscal adjustment deemed necessary for long-term fiscal stability. Some other reforms were targeted at areas that were not the key obstacles to growth at the time – such as weakening collective bargaining or making it easier to fire workers, which tends to lower spending in a depressed economy or pushes more workers onto an already congested labour market. Reforms directed at the key bottlenecks, which we discuss below, were rare.

Third, some reforms only work in combination with others. There is little use in reforming business and contract law if the judicial system remains unable to enforce it in a timely manner. Cases in civil and administrative courts take years to be resolved, according to several studies.3 The system is bogged down by inefficiencies and a huge backlog of cases. In Greece, some of the most basic underpinnings of a successful economy are in need of reform, which means that reforms of higher-level economic policy – such a more growth-friendly tax code or a simpler insolvency regime – are limited in their effect.

Those three challenges combined – the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, the scars of the euro crisis and the structural obstacles to economic growth – require a bold policy response, from the Greek government as well as European institutions, to ensure that Greece makes a full recovery from a decade of crises and grows sustainably thereafter.

The most important task is to manage the current crisis well. Many European countries, Greece included, are undergoing long lockdowns to bring infections down, which shows that governments acted too late to contain the virus effectively. This is economically much more costly than locking down early to contain the virus’s spread. Greece has also been hit hard this time, with deaths per 100,000 citizens reaching much higher levels than during the first wave.

Greece has done well in supporting workers, households and businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lockdowns are economically very costly, so it is important that governments provide ample support to workers and businesses. The factories, stores, brands and know-how of firms are worth protecting as those features of a business are costly to rebuild. The same is true for workers’ firm-specific knowledge, which would be lost if they became unemployed. Maintaining businesses that were profitable before the pandemic and keeping workers in jobs, even if they currently cannot work, is good economic policy. What is more, governments need to support part of workers’ incomes in any case. Sending workers into a crowded labour market in search for work just means the income support will be needed in the form of unemployment benefits.

Greece has done well in supporting workers, households and businesses: it has provided cash payments to workers and the self-employed and allowed employees to work shorter hours. It has subsidised hiring by firms under certain conditions and has provided them with cheap loans. It has extended some social benefits, and it introduced rent relief and contributed to the mortgage payments of eligible households. The entire support package is expected to cost €31 billion, which is around 16 per cent of 2019 GDP. Despite its high public debt, Greece needs to continue with these measures, and top them up if needed, to allow most of the economic fabric of the country to survive the crisis.

Greece’s banks also need to continue on their long path to repair their balance sheets. The banks’ situation was already difficult before the crisis hit. They had devised plans, which are now common in Europe, to reduce their non-performing loans: put the distressed assets into a fund, issue two or three different claims on that fund (‘securitise’ it), some of which (the ‘senior’ claims) rank higher than others and thus face a lower risk of default than the ‘junior’ claims, and sell the junior tranches to the market. The senior tranches then represent the relatively healthy parts of the assets – but a public fund, aptly called Hercules, adds guarantees to these senior tranches so that they count as good assets.

The pandemic is adding more bad loans, but interestingly also more demand from international investors for those securitised assets, because they are seeking higher returns in a period of very low interest rates. The government should use this high demand to make the clean-up of the banking sector one of its highest priorities. Greece’s central bank has proposed a ‘bad bank’ to take on distressed assets that the private sector struggles to offload elsewhere. That proposal is worth pursuing, as it may speed up the clean-up, which would benefit the economy as a whole – a positive effect that banks do not take into account when making decisions on how to deal with bad debt. The economy will always struggle without a healthy banking sector that is ready to fund businesses.

The next task is to get the Greek economy to grow sustainably in the future. That requires both Greece and the European Union to contribute.

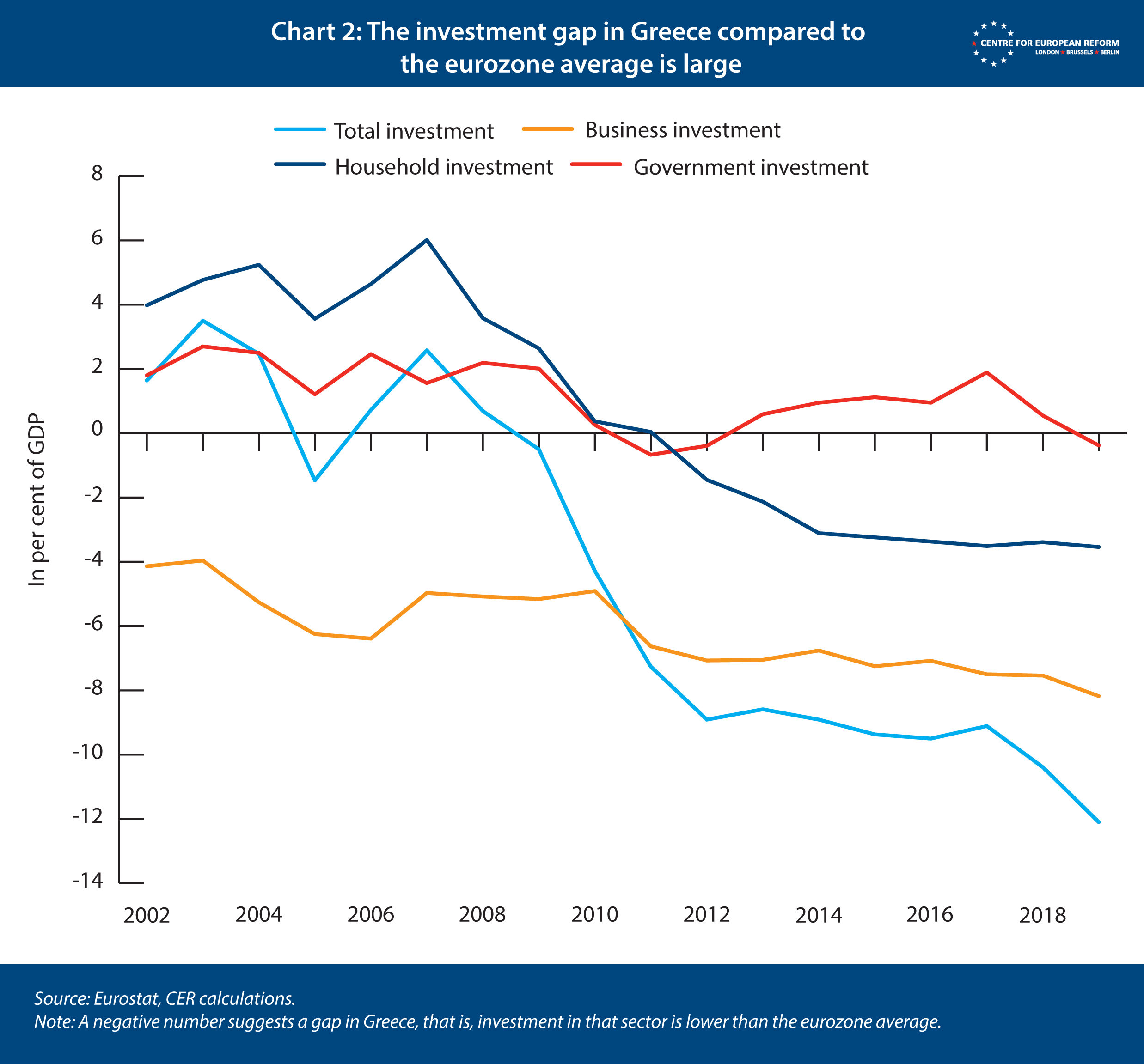

Greece needs to continue to tackle the bottlenecks that hold back its growth. In a ‘growth diagnostics’ framework pioneered by Harvard economist Dani Rodrik and co- authors, the starting point is to ask why there is low investment.4 As Chart 2 shows, Greece has had lower business investment than the eurozone for a long time. This can be either because the returns on investment are low, or because funding such investments is too difficult.

Investments serving the Greek market are limited not just by the market’s size, but also by weak demand after years of crises and strained balance sheets. Investment focused on serving export markets stands a much better chance of being profitable.

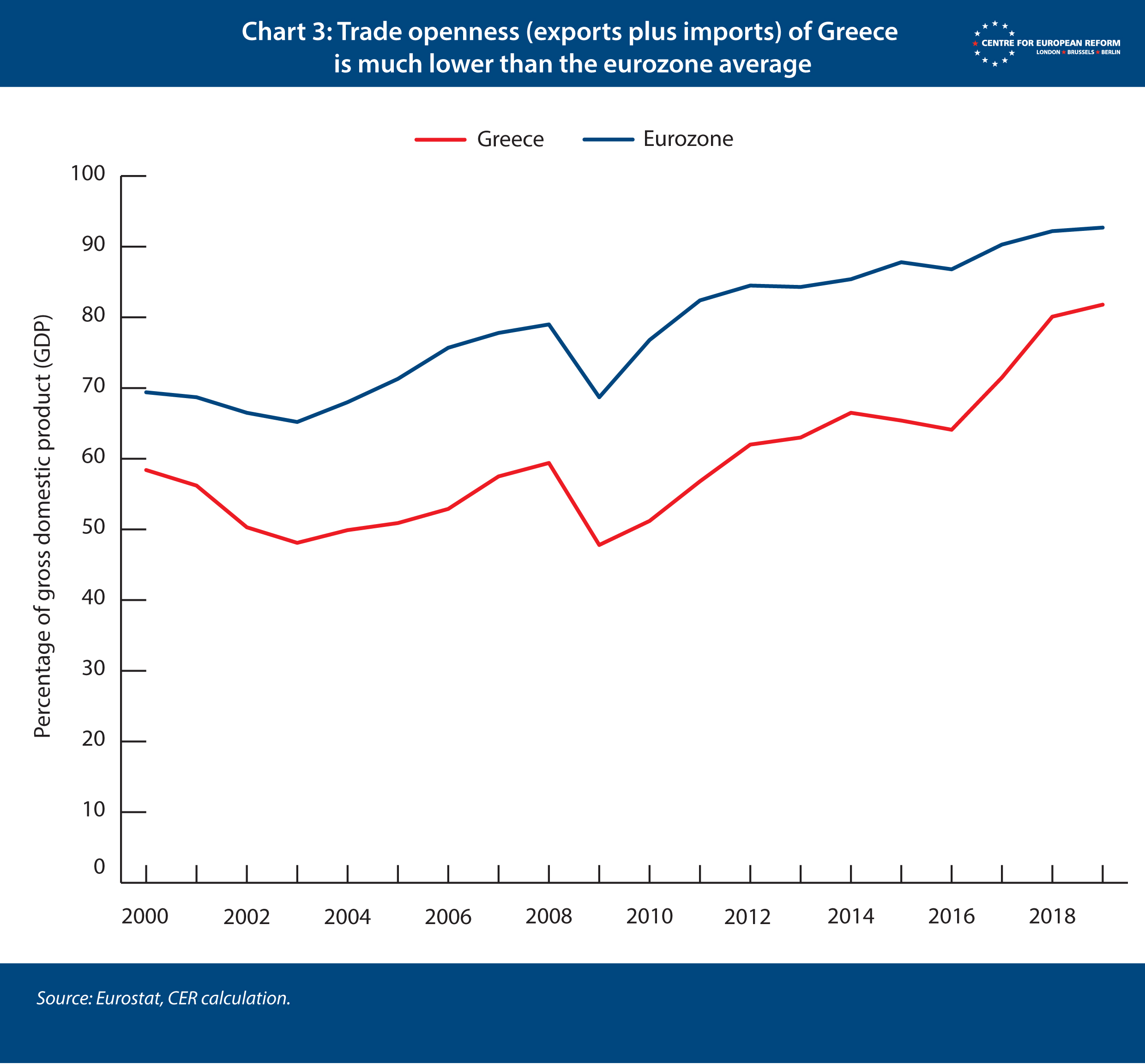

But one striking feature of Greece’s economic performance over the last decade is the weakness of exports. Considering that all EU countries, being members of the single market, have similar export opportunities and face few obstacles to trade within the EU, the reasons must be domestic.

Unable to devalue its currency, Greece resorted to ‘internal devaluation’ after 2010 – cutting wages to lower producer prices. But this has not worked well. The country’s unit labour cost – a measure of labour costs per unit of output – has come down considerably since 2010, as has its real effective exchange rate – a weighted average of exchange rates with its export partners, corrected for inflation. Both signal a sizable gain in price competitiveness, but export growth has nevertheless been disappointing (see Chart 3).

Greece’s mix of exports is unusual. It exports tourism, shipping and trade services as well as refined petroleum products in large amounts, but is underrepresented in categories that other high-income countries typically export. Put differently, Greece’s export mix is not that of a highly developed country: it exports too few sophisticated goods and services – its share of high technology exports in total exports is the lowest in the EU27 – and cannot compete on price or expand production of some of the less sophisticated products as easily as emerging markets.5

There is thus a large upside in investing in potential export sectors, which can build on existing clusters. Tourism is a prime example: the tourist season in Greece is too short, the offers too limited and the combination with conference travel or medical tourism underdeveloped. Food processing and generic pharmaceutical production are other examples of existing sectors with export potential to build on.

But can individual companies tap into that potential? One problem is that many Greek firms are small. Bigger companies are needed in the high-end tourism sector, for example, because size facilitates the necessary investment in marketing, technology and scale. Bigger companies could also more easily co-operate with other sectors, for example in building brands in medical tourism. Finding qualified staff is another issue, as studies have found weak digital skills among the Greek adult population, which are needed for more sophisticated jobs.6 Increasing exports is hard. It requires a bold combination of policies, including a clear industrial strategy, to make progress.

The Greek government has submitted its National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) to the European Commission to access the new EU recovery fund.7 It is based on recommendations by a high-level commission, chaired by Nobel laureate Christopher Pissarides. The plan rightly puts an emphasis on increasing private sector exports, and aims to increase the size of firms, improve their digitalisation and provide the workforce with more training. Achievements in these areas should allow the profitability of further investments to rise.

Turning to whether funding of investments is a critical bottleneck, there are two ways to gauge this: first by looking at access to finance for domestic entrepreneurs, and second by assessing investment funding from abroad.

Domestic funding is severely impaired by the troubled state of Greece’s banking sector, and because many firms, which may be willing to invest, cannot do so because they owe debts that they cannot repay. Adding to that, the Greek tax system demands tax payments upfront from small entrepreneurs, even though start-ups make losses in their first years in business, especially in the most risky, innovation-driven sectors of the economy. The pandemic has added to these funding problems for Greek entrepreneurs, leaving profitable investments that could propel growth unrealised.

In response to the pandemic, the government has provided an estimated €6 billion in liquidity to firms, with a focus on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This programme, via the Hellenic Development Bank (HDB), should now be turned into a strategic instrument to support the funding of Greek entrepreneurs and growing export businesses. The Greek NRRP proposes precisely that: using the loans offered by the EU to fund long-term private investments. For a fiscally constrained country such as Greece, this is arguably the best use of the cheap loans on offer. Greece’s EquiFund, which pools resources from European and domestic sources to provide start-ups with equity funding, could also be expanded, as risky equity funding is what mostly drives innovation.

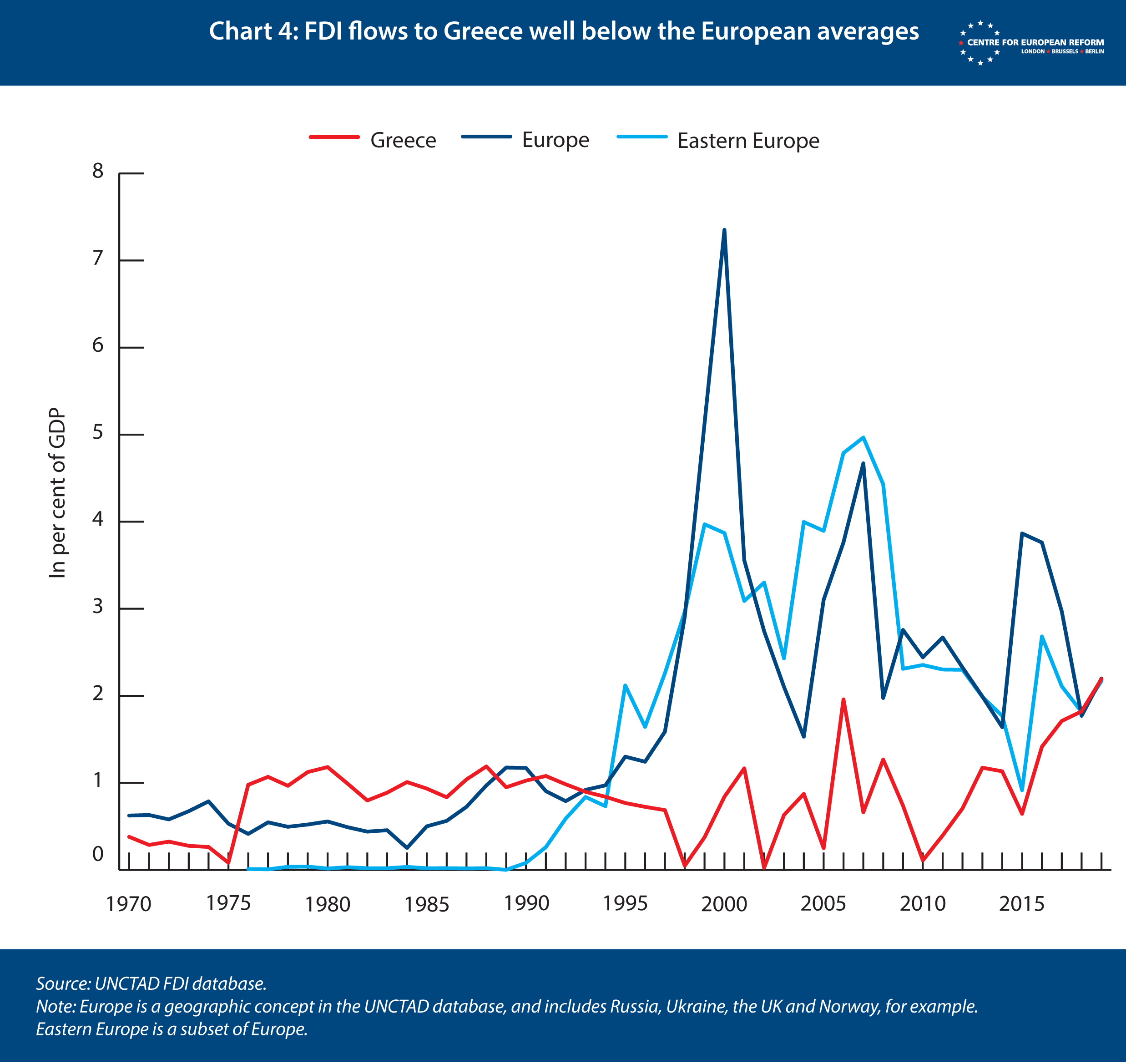

Funding from abroad for investments comes in two forms. Foreign investors might lend via Greek banks or buy shares in the Greek capital market. The alternative is foreign direct investment (FDI), that is, investors from abroad providing large amounts of risk capital to Greek firms or setting up firms directly. The more important of the two for economic growth is FDI, and Greece has performed poorly on attracting it in the past (see Chart 4).

FDI to Greece serves multiple purposes. It provides funding – which is domestically in short supply – for relatively risky ventures. FDI is often in export-oriented sectors and helps to create larger firms than Greece currently has. Foreign investors also tend to bring technological or organisational knowledge and capital, which ideally spills over to local firms, for example through connecting local and global supply chains, or by workers moving to other firms. Empirical research is mixed, but there is some evidence that FDI needs to be matched with domestic policies to promote innovation by domestic firms for such spill-overs to work well.

Spill-overs also tend to be bigger when domestic firms are larger.8

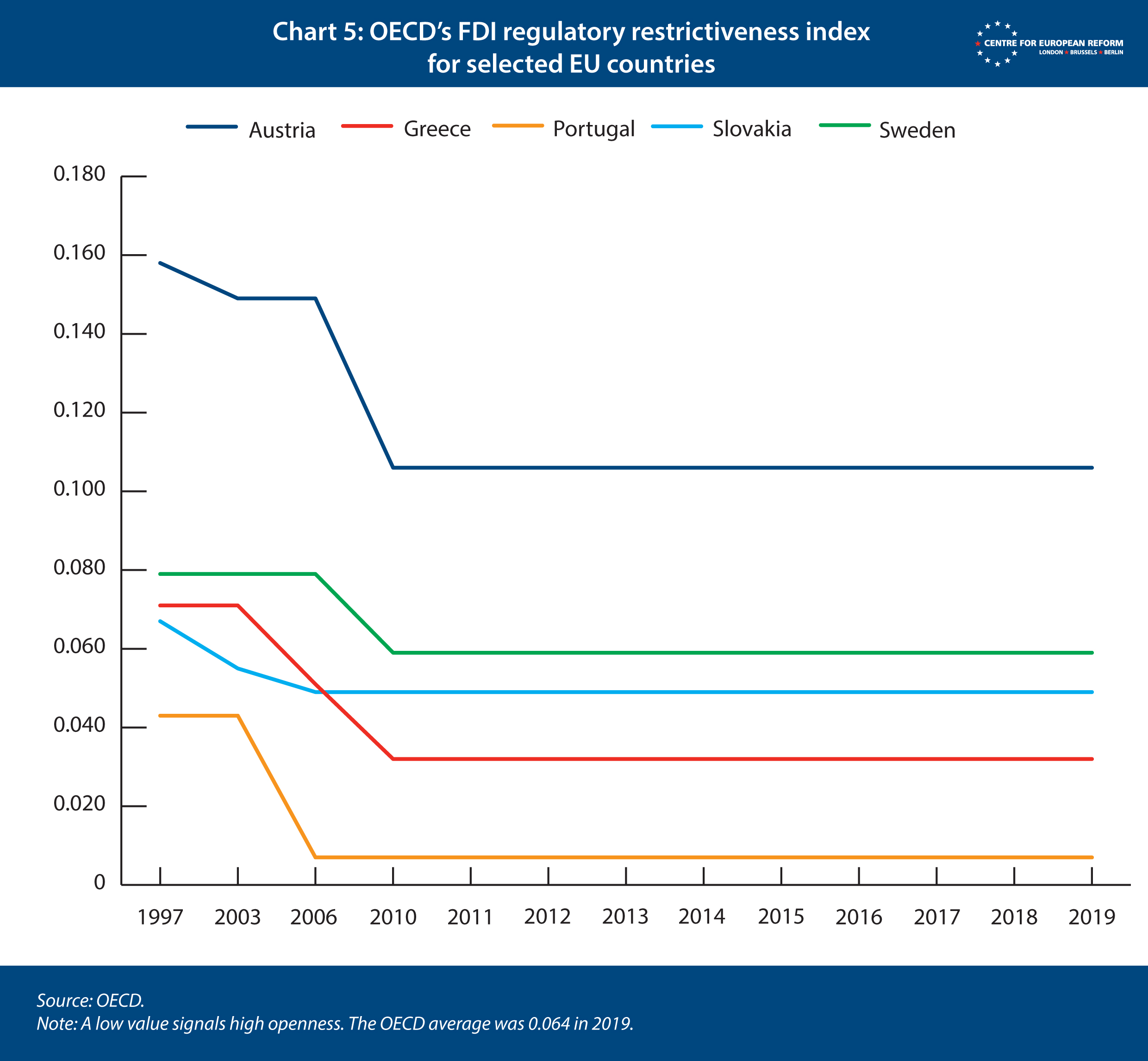

Just as with exports, the reasons for Greece’s underperformance on FDI are complex. Legal restrictions are not the culprit: in the OECD’s index of legal regulatory constraints on FDI, Greece is more open than the average OECD country (see Chart 5).

Research on the determinants of FDI shows that the quality of institutions and rules matter for potential investors – for example, predictable administration and business regulation, a functioning land registry, a speedy and fair judicial system and the like. Every Greek government proposes policies to improve the country’s administration and judicial system, and the current government is no exception. But the EU’s recovery fund provides a unique opportunity to make a big investment in the modernisation and digitalisation of the Greek public sector and judicial system. The government plans to do just that, in addition to using the funds to promote innovation in local companies and increase the size of firms, which should improve the spill-overs from future FDI to the local economy. But Greece has a steep hill to climb, and such far-reaching reforms and investment programmes will require a strong focus on implementation. Greece should make use of all the technical help that is on offer from the EU and other institutions.

But it is not just Greece that needs to support its own growth; the EU has a role to play, too. The first is to help the weaker countries through this crisis, which has already caused further divergence in Europe.9 The EU’s recovery fund is the boldest spending initiative in the EU’s history and rightly considered a major success of European integration. The amount that Athens can expect to receive in grants over the 2021-28 period is around €19.5 billion (roughly 12 per cent of 2020 GDP, plus another €12.4 billion in cheap loans). Greece can expect a very large growth boost of about 2 per cent a year from the grants alone for the first few years of the programme.

The EU should take bold steps to further reform the eurozone and strengthen aggregate demand.

It is now crucial to make that spending a success. That requires the European Commission to critically and consistently evaluate the national reform and investment plans that governments are obliged to submit. While national governments could well complain about this ‘interference’ in national affairs, they may privately welcome such stringency because it gives them a stronger hand in domestic negotiations over how the money is spent. Greece’s plans on investment and reform have set the right priorities. Contrary to the record of the last ten years, the reforms can be paired with considerable investment funding, as opposed to spending cuts. Like every country, Greece’s efforts should be measured against the goals it set out in its plan.

The second thing the EU should do is to take bold steps to further reform the eurozone. The banking union remains incomplete and the capital markets union is more of an ambition than a reality. Both ‘unions’ would help the entire eurozone, but they hold great promise for smaller countries: the funding of their economies would be made easier and more diversified, and their place in the monetary union would become more secure.

The third priority for the EU is to make sure that aggregate demand is strong enough to help all economies to recover, not just the strongest. Both fiscal and monetary policy need to be very accommodating in the years to come. Europe’s fiscal rules were conceived in a different time, when public debt was – in many ways wrongly – seen as a major problem in Europe. In truth, the funding costs of public debt have fallen so much since, that reducing debt will offer little economic benefit over the coming years. But cutting spending to reduce debt levels has large costs if it inhibits a full recovery. Instead, the focus needs to be on economic growth and how to promote it, at all levels of European policy-making. That will bring down levels of public debt in the process, and leave future generations with stronger, fairer economies and a more united Europe.

2: Macropolis, ‘BoG warns pandemic will leave trail of bad loans, hastening need for new tools‘, January 22nd 2021.

3: Macropolis, ‘The Greek justice system explained‘, 2017 a European Commission, ‘The 2019 EU justice scoreboard’, 2019.

4: Ricardo Hausmann, Dani Rodrik and Andrès Velasco, ‘Growth diagnostics’, mimeo, 2005.

5: Ilias Lekkos, Paraskevi Vlachou, Irini Staggel and Vasilis Pilichos, ‘Greek export performance: tangible signs of improvement but much more is required‘, Piraeus Bank, March 2019.

6: OECD, ‘Skills matter’, November 2019.

7: Government of Greece, ‘Strategic directions of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan‘, November 25th 2020.

8: Researchers have looked at the link between growth and FDI from various perspectives. An overview is provided in Nuno Crespo and Maria Paula Fontoura, ‘Determinant factors of FDI spillovers – what do we really know?‘, World Development, March 2007.

9: Christian Odendahl and John Springford, ‘Three ways COVID-19 will cause economic divergence in Europe’, CER policy brief, May 2020.

Yiannis Mouzakis is co-founder of MacroPolis and Christian Odendahl is chief economist at the Centre for European Reform

February 2021

View press release

Download full publication