Learning to live with debt

- The Biden administration has passed a massive stimulus bill and has proposed a large investment package. That will put pressure on European governments to commit to more spending too, and beef up the EU’s recovery fund and national investment plans. It will also add fuel to the European debate around public debt and when to start reducing deficits.

- European states can sustain high debts, and have to play the role of insurer for large risks such as the pandemic. Unlike households, states are long-lived, have a fair amount of control over their own revenues and issue bonds that are attractive because they offer safe stores of value for investors.

- But Europe’s consensus on debt and inflation remains relatively hawkish, and assumes that the inflationary forces of the 1970s are still intact – when in fact the world economy has changed dramatically. The effects of ageing, high levels of income and wealth inequality, and of private debt, alongside strong global demand for safe assets, all indicate that aggregate demand and inflation will continue to be weak for the foreseeable future, unless governments act very boldly.

- Europe needs a new consensus that recognises the benefits of higher public debt, such as increased public investment and more safe assets to invest in, and is less obsessive about the potential costs of debt. Low interest rates are most probably here to stay; and faster growth, not austerity is the best way to stabilise public debt.

- Nor should that new consensus shy away from debt monetisation as a potential safety valve. Central banks are public institutions, and can be enlisted to help states fund themselves in times of rising interest rates. The risk of temporarily higher inflation should be seen as part of a cost-benefit analysis, and not something to avoid at all costs.

At the time of writing, the pandemic is continuing to take a heavy toll on the European economy, and even though an economic collapse has been prevented, Europe’s growth prospects are far from encouraging. Policy-makers across Europe have supported firms, workers and families through furlough schemes, income support and loans – often with remarkable pragmatism – and are continuing to provide new forms of aid. The European recovery fund offers €750 billion in grants and loans to poorer and harder-hit countries. But policy-makers in Europe are reluctant to use the full arsenal of the government balance sheet to spur a full and swift recovery in the way the new US administration is doing, as the fear of higher public debt starts to dominate the European debate (again).

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and the ensuing crisis in the eurozone, those in favour of a swift end to fiscal support won the argument, causing widespread economic harm. This time, European policy-makers should act differently. Their foremost concern should not be public debt, but how to support a swift economic recovery, reach full employment, and bring inflation back to its target level of 2 per cent. This policy brief reviews the costs and benefits of higher public debt in Europe and how today’s world economy is very different from the one that inspired the old consensus.

The state as insurance

A crucial function of the state is to provide and organise insurance to guard against risks, such as health, unemployment, poverty and ageing. These risks include ‘macro risks’ against which the individual cannot take out any form of private protection, such as economic crises, deindustrialisation, natural catastrophes or pandemics.

A crucial function of the state is to provide and organise insurance to guard against risks such as pandemics.

There are three reasons why states can and must provide this insurance. First, states are long-lived. States do not have to repay debt, unlike people (if they want to protect their credit score). States can simply roll it over or pass it on to the next generation. If that sounds worrying, it also means that state debt provides a perpetual piggy-bank for investors. The state will be there for generations, paying interest, repaying old debts and issuing new ones.

Second, states have coercive tax powers, which means that they have a degree of control over their own revenues, and do not need to put up collateral even when borrowing large amounts of money. A government, unlike a firm or a household, is not dependent on a limited income stream from a job or line of products. Whether a factory produces, say, diesel or electric cars, the government has the power to tax all forms of economic activity, and ultimately, the state’s revenue source is the economy’s GDP. Since governments are very reluctant to default on their debt, a government bond is implicitly collateralised by future tax revenues.

Third, rich countries issue the currency in which they take on debt; individuals do not. (Poorer countries often issue debt in a foreign currency to attract investors.) That makes the public debt of rich countries the safest possible asset, as governments can technically never run out of money. They can simply order the central bank to provide more. Because of that status as a safe asset, government bonds have not faced a shortage of demand during the pandemic. On the contrary, in dire circumstances government bonds are often the safest place for private investors to hide.

The euro is a shared currency, issued collectively by the members of the eurozone through an independent institution, the European Central Bank (ECB), that cannot easily be forced to print money as it is the sole decision-maker on monetary affairs. The main reason is that the eurozone is a monetary union without a strong fiscal and political union. There is thus self-inflicted doubt over whether it will live forever or break apart. That means future tax revenues, which form the implicit collateral of government debt, could be denominated in a different, lower-valued currency if the euro broke apart.

But those are political rather than economic problems. No country has left the euro, despite the crises, and most populist parties no longer advocate euro exit. Moreover, since 2012 the ECB has finally started behaving like a normal central bank, and taken on, in all but name, the role as the eurozone’s lender of last resort. During the pandemic, the ECB has followed up with a big programme of bond purchases called the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), making it clear that the bank stands behind European public debt – so long as debt is deemed sustainable – should markets turn against governments.

The old macroeconomic consensus no longer fits

A bold central bank that unequivocally stands behind public debt gives governments further freedoms. Not too long ago, that was a cause for concern. Democracies, it was argued, were prone to inflation due to profligate government spending and other policies that resulted in unsustainable wage growth. The stagflation of the 1970s – when low growth and high unemployment went hand-in-hand with high inflation – seemed to prove the sceptics right. Central bank independence became a key element of the macroeconomic reforms that followed, not least because the famously independent German Bundesbank curtailed inflation earlier than its peers in the 1970s.

The other defining component of the macroeconomic rethink of the 1970s was an emphasis on limiting budget deficits and keeping public debt low. The fear was that governments, stripped of their direct control over monetary policy, would be tempted to go on a spending spree instead. The resulting high debt would eventually undermine the independence of the central bank, as governments could try to force the central bank to buy bonds to fund governments. That in turn could generate inflation. Moreover, high debt could lead to high interest rates, as investors lost trust in the government’s ability to keep debt stable, burdening future governments and taxpayers.

Applying these policy principles in the early 1980s delivered a severe shock to the US and European economies. Unemployment surged as inflation was brought under control. What followed is often called ‘the Great Moderation’ by economists, a period of low inflation, declining interest rates and relatively stable public debt. But several economic forces have changed considerably since the 1970s and 1980s, and should inform Europe’s policy response today.

The first is the relative power of inflationary forces, notably the bargaining power of labour. Since the 1970s, labour’s share of income, as opposed to income that flows to the owners of shares and other forms of wealth, has declined considerably across advanced and emerging economies for many reasons including the decline of labour unions, globalisation, technological progress and government policies. When a larger share of income goes to the rich, who save more of it than the poor, demand declines – unless new investment creates additional demand.

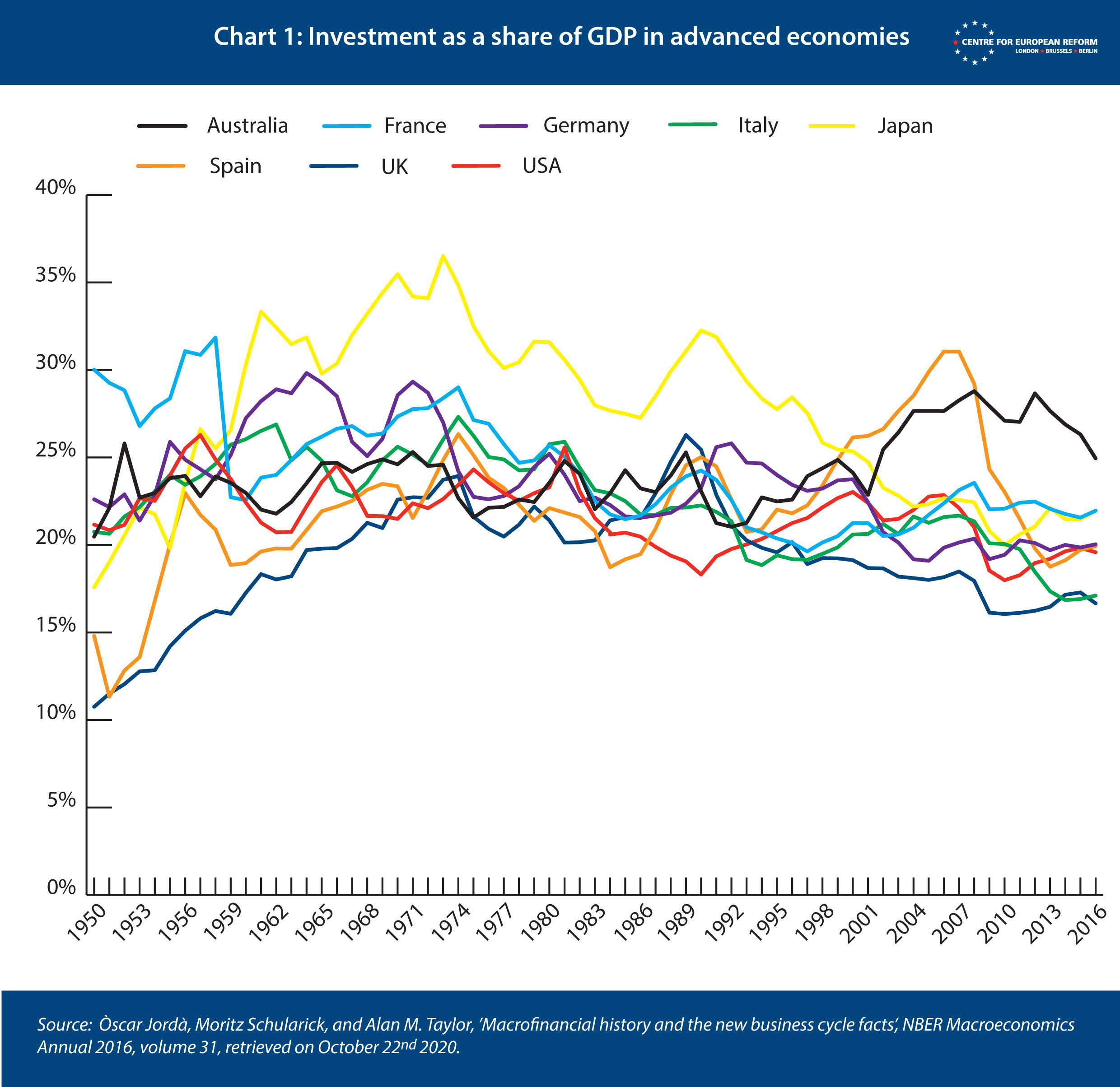

But the world is running low on investment opportunities to offset the lower consumption demand that comes with unequal distribution of income. Investment as a share of GDP has been remarkably stable for decades (see Chart 1), and there may be less need for machines and factories in the era of digital technology and globalisation. Other ways of recycling the surplus savings of the rich have failed, too. The subprime mortgage boom and bust of the 2000s has showed the limits of the US as the consumer of last resort. And China’s state-led investment boom – China invests more than 40 per cent of its national income – cannot compensate for under-consumption at home and abroad for much longer. The world has a demand problem, and unless there is a major shift in bargaining power towards workers and thus a shift in income away from the rich, it will continue to have one for the foreseeable future. A large short-term stimulus might generate some inflation, but the re-emergence of sustained inflationary pressure, as seen in the 1970s, is unlikely.

Second, the world has run up private debt to unprecedented levels, and the pandemic has increased that debt further. Such a large stock of private debt may have a deflationary effect. Those that might desire debt – households that want to buy a house or firms seeking to invest – have strained balance sheets, and cannot take on more; instead they use more of their income to service and pay down debt. In aggregate, firms in advanced economies have become net lenders over the past decades: instead of borrowing money to invest, like they used to, they save and accumulate assets. By outpacing companies’ willingness to invest, corporate sector saving is contributing to the demand problem – and there is little reason to believe the trend will reverse.

Firms in advanced economies have become net lenders: instead of borrowing money to invest, they save.

Third, many advanced economies have ageing populations. The effect of ageing on inflation and interest rates is controversial. In theory, older societies may save less as retirees spend their savings; there may also be a shortage of workers, inducing firms to invest more in technology and machinery to replace labour, and leading to higher wages for the workers that remain. Both effects would tend to drive up inflation and interest rates. But so far at least, ageing has been deflationary. Politically, people also tend to become more averse to inflation with age because retirees usually own assets that pay them a regular nominal income, and that loses value if inflation rises.

Fourth, there is a huge demand for safe assets around the world. Safe assets play a crucial economic role. Some investors seek high, risky returns, but many just want a safe place to store their wealth. That includes businesses looking for somewhere to stash their cash holdings, workers close to retirement and also savers in emerging market economies that lack comprehensive pension schemes or a stable currency. In addition, banks are mandated through regulation to hold safe assets, while official investors such as central banks accumulate foreign reserves in order to stabilise their own currencies and financial markets.

As the strongest economy in the world and the issuer of the world’s reserve currency, US government debt is the benchmark safe asset. But European public debt is also viewed as safe, with a few exceptions. The EU’s first batch of bonds, issued to fund the bloc’s COVID-19 assistance packages, attracted huge interest from financial markets. Prices were high and interest rates low. That demand for safe assets will remain high for the foreseeable future – in fact, the crises since 2008 have only raised it, as the world is perceived to be less safe than before. And even if all advanced economies have much higher public debt after this pandemic, there are very few assets that risk-averse investors can turn to instead. No matter what is happening in the world, European public debt will remain among the safest of assets, keeping borrowing costs low.

A new approach to public debt

For these reasons, Europe needs a new consensus on public debt. The first tenet should be that low public debt can be costly, just as high debt can be.

Politicians fear that high debt could spark inflation, that rising interest rates may render government debt unsustainable, or that the cost of servicing high public debt could lead to higher taxes and have a detrimental effect on economic growth.

But the costs of low debt can be bigger, depending on the circumstances. The failure of governments to engage in debt-financed expenditure can result in a chronic lack of demand when the private sector is struggling. That can raise unemployment and lower growth and inflation. Low public debt contributes to the global shortage of safe assets, leaving investors with fewer ways to safely store money in liquid assets. And spending cuts that are designed to lower debt usually mean under-investment in infrastructure and public services, education or research. Such under-investment often hurts the poor more than the rich, undermines cohesion in society and can have long-lasting political ramifications.

What is more, public sector thrift in Europe can lead to financial instability elsewhere. When Europe consumes and invests too little, and saves instead, those savings must be put to use, so they get invested abroad through the financial system. Thus, the debt that Europe did not want to incur builds up elsewhere. That build-up of debt can suddenly go into reverse in a financial panic, causing financial crises. That means that both borrowing and saving countries lose. The global financial crisis and the euro crisis should provide ample warning.

Low public debt can also have severe political ramifications. The US has provided an outsized contribution to global demand in recent decades, but its willingness to be the consumer of last resort had limits. Donald Trump’s obsession with the US trade deficit – the flipside of being the consumer of last resort – and his protectionism have hurt Europe. Likewise, the UK’s vote to exit the EU was driven in part by high unemployment in the eurozone and the flows of migrants into the UK that followed and by austerity in Britain itself.1 There are also geopolitical considerations outside the West: so long as Europe is relying on China to provide demand that keeps European workers in jobs, European leaders may be timid about criticising Chinese expansionism or human rights abuses. And a global role for the euro as a reserve currency is simply unimaginable without an ample supply of European safe assets to invest in, that is, a deep, liquid market of European government bonds.

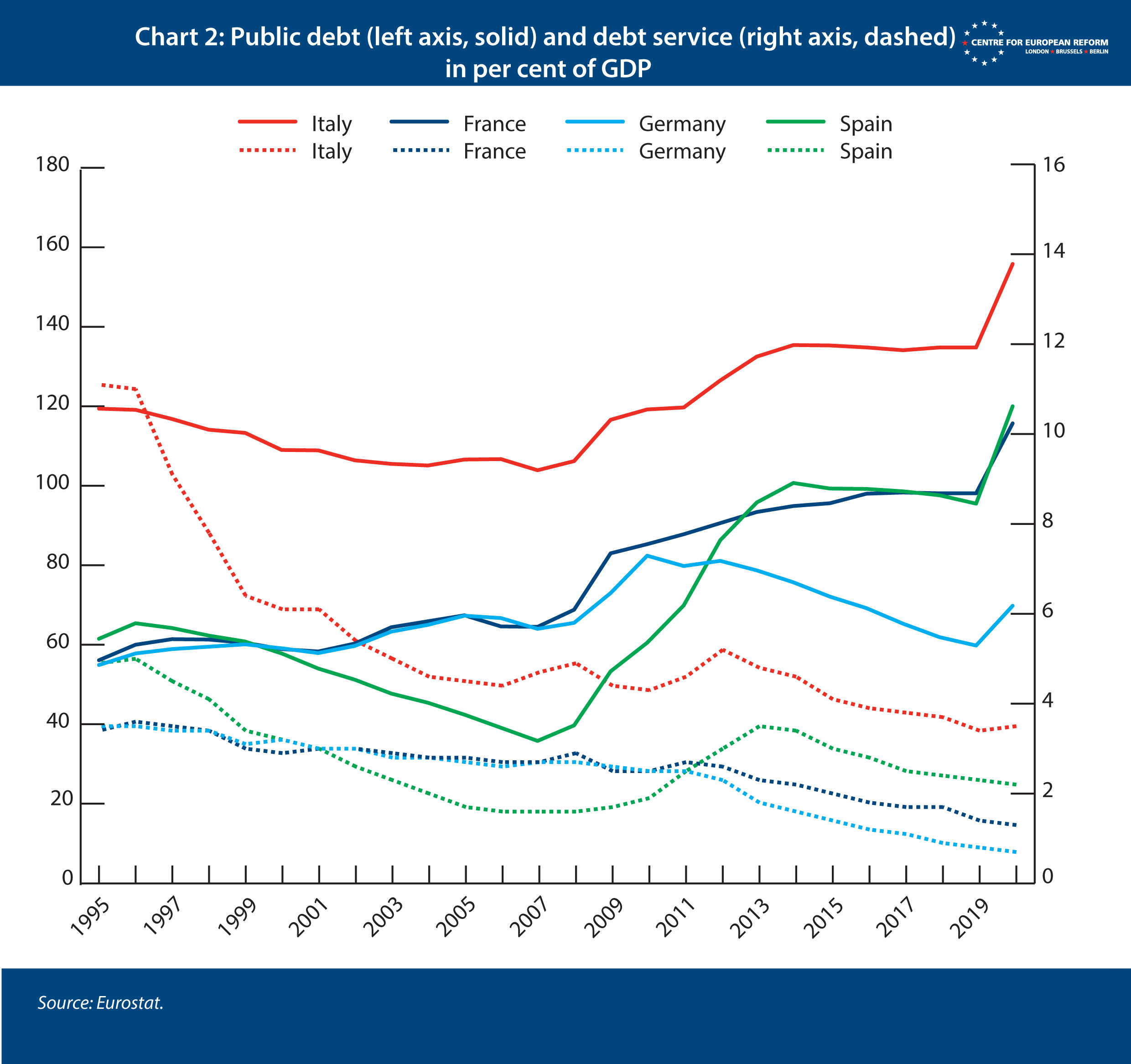

The second tenet of the new consensus should be that high levels of public debt are more sustainable than previously thought. European member-states need to be able to service their debt with future tax revenues. But in a world of excessive demand for safe assets and a chronic shortfall of demand, debt servicing costs are considerably lower than they used to be (see Chart 2).

Despite higher public debt, eurozone governments paid less in annual debt service in 2019 and than they did in 1995. France’s debt was almost 100 per cent of GDP in 2019, while Germany’s was 60 per cent, but the difference in the cost of debt service between them was very small. Currently, Germany and France are being paid to borrow, not just for short maturities but even for ten-year bonds. The German public debt that matured in 2019 had an interest rate of, on average, two per cent, whereas newly issued bonds had an average rate of just below zero.2 Recent calculations by the German finance ministry show that, if current interest rate levels continue, Germany’s debt servicing costs will fall to zero by 2029.

If current interest rate levels continue, Germany’s debt servicing costs will fall to zero by 2029.

Would it not be too risky to count on such low rates forever? After all, if rates increased, debt servicing costs would, over time, increase too. To see why this risk is lower than is often assumed, one must look at the relationship between the interest rate that governments need to pay on debt and the growth rate of the economy.

A rise in interest rates is not sufficient cause to worry about debt levels. The interest rate on public debt needs to be higher than the nominal growth rate of the economy – real growth plus inflation – for debt to become a problem. So long as the interest rate remains below the growth rate, the public debt stock is sustainable because it will automatically fall relative to the size of the economy over time. In these circumstances – as even the German ‘council of economic experts’ argued in their 2007 study that laid the foundation for Germany’s ‘debt brake’ – a debt limit cannot be convincingly justified.3

Interest rates that surpass growth rates are very unlikely to happen in the foreseeable future. Higher interest rates for government debt will almost certainly stem from higher growth and inflation – interest rates do not magically increase all on their own. The reason that the interest rates on US government debt began to rise at the beginning of 2021 was precisely because investors became dramatically more optimistic about the prospects for the US economy, on the back of a large fiscal stimulus by the Biden administration. They were not worried about the increase in debt. It is true that in the past, some European countries have seen interest rates higher than their nominal growth rate. But the world has changed, and for most countries in Europe (and certainly for Germany and France) higher levels of public debt are far more sustainable than previously thought.

The third tenet should be that economic growth, and not austerity, is the best way to stabilise debt. Consider the budget surplus that Italy needs to run to keep its public debt at the current level. That surplus depends on the nominal growth rate of the economy, the nominal interest rate and the debt stock, which now stands at roughly 160 per cent of GDP. If the Italian economy had no growth or inflation at all in the future – and assuming an average interest rate of 2 per cent on Italian debt – the Italian government would have to run a 3.2 per cent budget surplus (before interest payments) indefinitely to keep public debt at today’s level relative to GDP. If Italy’s growth rate plus inflation was instead 0.5 per cent, stabilising the debt level at 160 per cent of GDP would require a surplus of just 1.6 per cent of GDP.

The focus of policy-makers therefore needs to be on fostering growth, not on cutting deficits and debt. Fiscal spending is part of that focus on growth: public investment has high overall returns, especially so in times of high uncertainty and low inflation. Investment in education, innovation and research needs to be a priority if Europe is to face the challenges of an ageing society and rapid technological change. And tackling climate change through investment is an imperative for the sake of the younger generation.

The common argument that public debt burdens future generations is false, if money is spent productively. The capital stock of the economy grows as a result of public investment, and the economy derives a benefit from that larger capital stock. If that benefit from a larger capital stock and the overall growth of the economy turns out to be higher than the current interest rate on public debt, there is no burden on future generations. Instead, they gain from the increase in borrowing. Considering that interest rates are currently around zero, many debt-funded public investments will be a net gain for future generations, even accounting for the fact that returns on public investment and economic growth may vary.

The fourth tenet should be that the ECB’s balance sheet is a legitimate safety valve to manage public debt. Central banks around the world have bought large amounts of longer-term public debt, not to finance governments but to stimulate the economy after short-term interest rates hit zero. This has made funding for governments easier, but the fiscal impact is often overestimated: the deeper reasons for low interest rates, including on government bonds, lie elsewhere. The ECB has, in all but name, also made itself the lender of last resort to governments, meaning that the ECB will contain market panic in government bond markets if there is a crisis, as long as the bank deems debt levels to be sustainable.

But if, in the future, interest rates did rise by more than the nominal growth rate for some reason, and the sustainability of, say, Spanish debt came into question, the ECB would have to make a choice: whether to help the Spanish and other governments fund themselves or not. There are several options. The ECB could keep Spanish government bonds on its books and roll them over when they come due, in effect becoming a regular buyer of EU government bonds, even when interest rates are above zero. But that would only be small relief, as the effect of ECB bond-buying on interest rates is small. The ECB could also more actively manage long-term interest rates – like the Bank of Japan has done recently to raise growth and inflation, and the US did after the World War II to keep funding costs of public debt low. One way to do so would be to cap long-term interest rates at a certain level, and buy as much government debt as is needed to maintain that cap. That way, the ECB could more directly control the longer-term interest rates that governments have to pay on their debt, even if that risks inflation.

By using all the monetary tools available, the ECB can act as a safety valve to prevent a too-rapid increase in the interest rate on government bonds in the future. That might help governments with the transition to a higher interest rate world, if and when it comes. It is conceivable that using the ECB’s balance sheet in this way might involve higher inflation. But after years of undershooting the inflation target, temporarily overshooting the target could hardly be regarded as imperilling price stability. Given the prevailing balance of power in the labour market and the slack within most labour markets in Europe, the chances of unleashing a sustained period of high inflation are low. The inflationary expectations of investors and consumers are firmly anchored, and the last decade shows that convincing people to change their expectations in either direction is, in reality, quite hard.

If inflation does need curbing in the future, the ECB would know what to do – raise interest rates to the appropriate level. It is far easier to tackle inflation than to fight a deflationary spiral, which would be the probable outcome of governments trying to reduce debt levels rapidly once the pandemic is over. Temporarily higher inflation, and the resulting weaker euro, may cause a small adjustment in income and wealth between different types of asset holder. But it would simply reverse a balance which for so long has favoured those who do well under low inflation, like owners of bonds who have low debts themselves. All policies involve such trade-offs. Not everyone benefits from an obsessive focus on fiscal rectitude and price stability, and that simple fact should be part of the debate.

Using the ECB as a safety valve for public debt will not lead to high inflation, and certainly not hyperinflation. Partial debt monetisation should not be a taboo, but part of any cost-benefit analysis of public debt and the democratic deliberation around it. After all, higher public deficits have benefits, such as protecting people’s incomes through the pandemic or investing in much-needed public goods. Those benefits are the flipside of a small risk of somewhat higher inflation in the future. Europe’s fiscal framework and monetary setup was put together with a different world in mind than the one we live in today. It is high time to adjust that framework, to ensure that Europe can fully and swiftly recover from COVID-19.

2: German Federal Ministry of Finance, ‘Kreditaufnahmebericht des Bundes 2019’, July 2020.

3: Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung, ‘Staatsverschuldung wirksam begrenzen‘, March 2007.

Christian Odendahl is chief economist at the Centre for European Reform

Adam Tooze is director of the European Institute, Columbia University

May 2021

View press release

Download full publication