Europe shouldn't worry about inflation

The fear of inflation is stalking Europe again. Policy-makers are right to be relaxed.

Inflation is no near-extinct tortoise that suddenly reappears unprompted. Nor is it a short-term fluctuation in the prices of certain goods and services during a disruptive pandemic. Inflation is a general rise in the level of prices in response to underlying economic forces such as employment, growth, the economic expectations of people, and policy-makers’ actions. For central bankers, inflation is a useful thermometer for the economy: if it is too low, it points to a cool economy that has unused capital or labour that can be put to use; if it is too high, it shows that demand is higher than capacity, which drives up prices too fast. A steady and predictable inflation of 2 per cent is ideal for Europe.

Europe’s problem over the last decade has been a cool economy: too little inflation pointed to an economy that was running below its potential. Policy-makers seemed unable (though mostly, just unwilling) to generate enough demand to bring the European economy back to its potential, and inflation back to a healthy 2 per cent.

As Europe is exiting the pandemic, it is crucial that policy-makers do not choke off the economic recovery out of a misplaced fear of inflation. In fact, a period of above-target inflation would be helpful to make sure that the economy really has fully recovered and that all capital and workers are employed. But pushing the European economy sustainably out of its low inflation mode of the last decade towards rates above 2 per cent is not easy. Of the five ingredients that are needed to achieve sustained inflation, Europe currently has none.

Getting #inflation sustainably above 2% is not that easy. It requires 5 ingredients, of which Europe has none.

Ingredient 1: Overstimulate your economy

In the US, the Biden administration quickly got to work after the inauguration and announced major spending plans. The most important was the ‘Rescue Plan’ of $1.9 trillion, which sent $1,400 checks to individuals (and their children) earning less than $75,000 per year, extended child tax credits and ‘earned income’ tax credits, and extended an uplift in unemployment benefits. In particular, those in the bottom half of all income earners were given a sizeable boost to their take-home income, with those in the bottom fifth receiving a 20 per cent increase. Poorer people tend to spend extra take-home income quickly, boosting consumption across the economy. The Rescue Plan came on top of an economic relief plan of $900 billion in December 2020. Even considering the pandemic, $2.8 trillion for economic relief and a stimulus is a very large amount.

Some economists feared at the time that such spending would overheat the US economy – that is, bring the US economy above what economists call ‘potential GDP’, when all resources of the economy are fully employed and additional demand merely leads to rising prices. Estimating potential GDP is very difficult. A reasonable estimate, made at the beginning of 2021 when the plan was announced, put the ‘output gap’ between economic activity and potential GDP at $900 billion, that is, not even half the spending of the Rescue Plan. That would imply that the plan, if most of the stimulus was spent quickly, would overheat the economy. Others argued that more demand would in fact expand the potential of the economy, for example by encouraging firms to invest and by motivating more people to return to work because of plenty of jobs with attractive salaries.

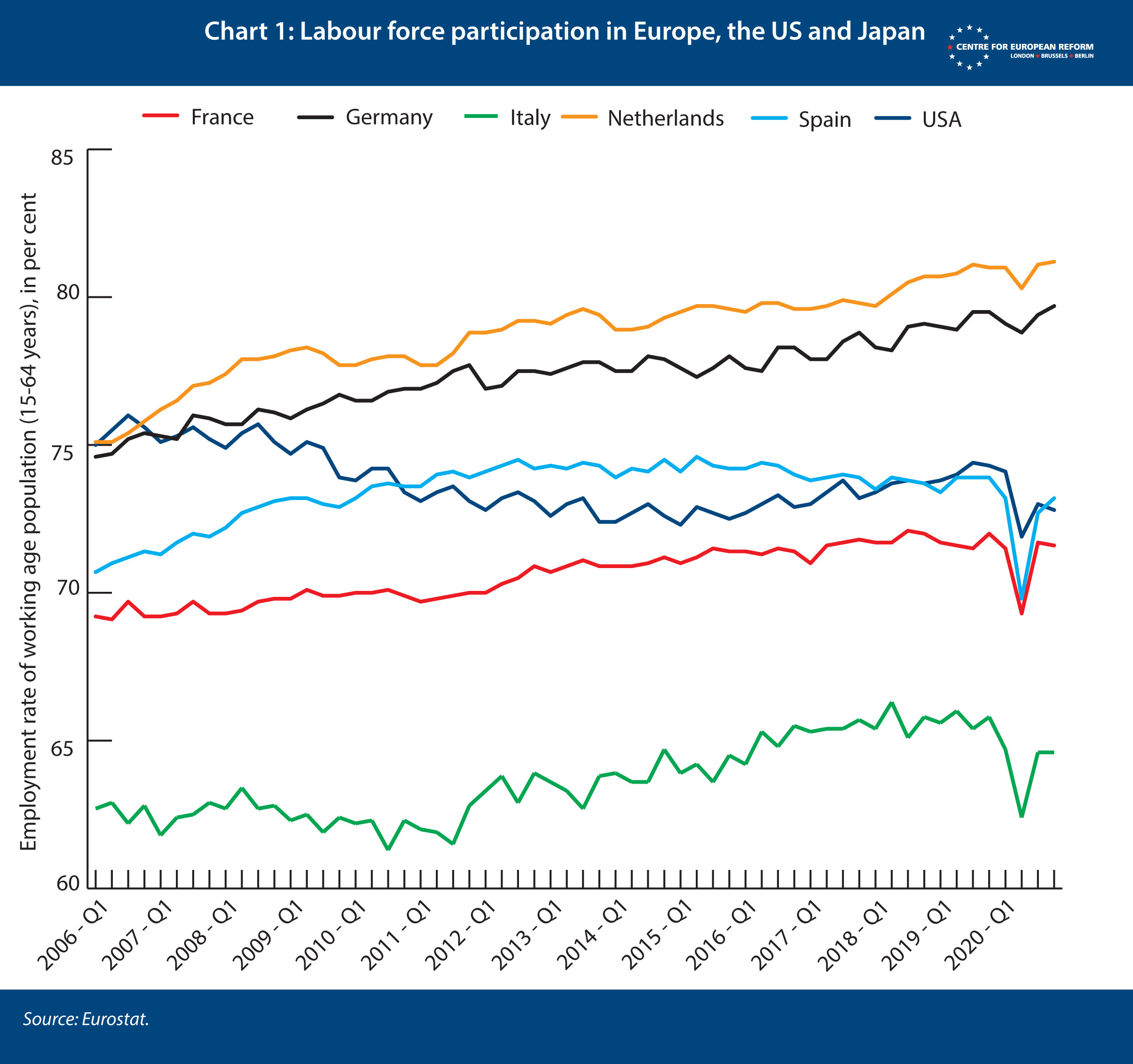

The proportion of working-age adults in employment in the US has fallen since the mid-2000s, and an 8 percentage-point gap with the employment rate in Germany and the Netherlands has opened up where there was none before (see Chart 1). More demand could close that gap instead of generating wage and price inflation. The Congressional Budget Office, a body that evaluates budget plans, seems to agree that US potential GDP is large and that Biden’s stimulus will not overheat the US economy much, despite a recent rise of inflation to 5 per cent. It now expects US consumer price inflation to reach 3.4 per cent on average in 2021, before coming down to 2.5 per cent from 2022 onwards – a level that the Federal Reserve is happy with, as it aims to let inflation run slightly above target for a while.

Estimates of output gaps in Europe have almost comically misjudged the state of the economy over the last decade. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) thought that Germany had reached its potential output and thus full employment in 2012, after which employment continued to grow, generating more than 3 million additional jobs by 2019 but no out-of-the-ordinary wage growth or inflation. The European Central Bank (ECB) famously predicted for a decade that inflation was just around the corner – except that inflation never came. Because European policy-makers constantly underestimated the potential of the economy, they failed to enact sufficient stimulus to reach full employment, leaving millions underemployed, and inflation and growth too low.

So how big is potential GDP in the eurozone today? The honest answer is: nobody knows. Institutions like the IMF or the ECB have to estimate potential output because it is part of their regular assessment of the European economy. But considering their track record and the current pandemic-related uncertainty, their estimates are not a helpful guide to the post-Covid economy. Chart 1 gives some indication that there is a lot of untapped potential in European labour markets, which could be tapped into with the right mix of policies. The gap in employment rates between France and Germany, or between Italy and Spain, is roughly 8 percentage points. The gap between Belgium and the Netherlands is even larger at 13 percentage points. That shows that some countries still have large untapped potential. It would take a very large stimulus, especially in Europe’s South, to overheat the European economy.

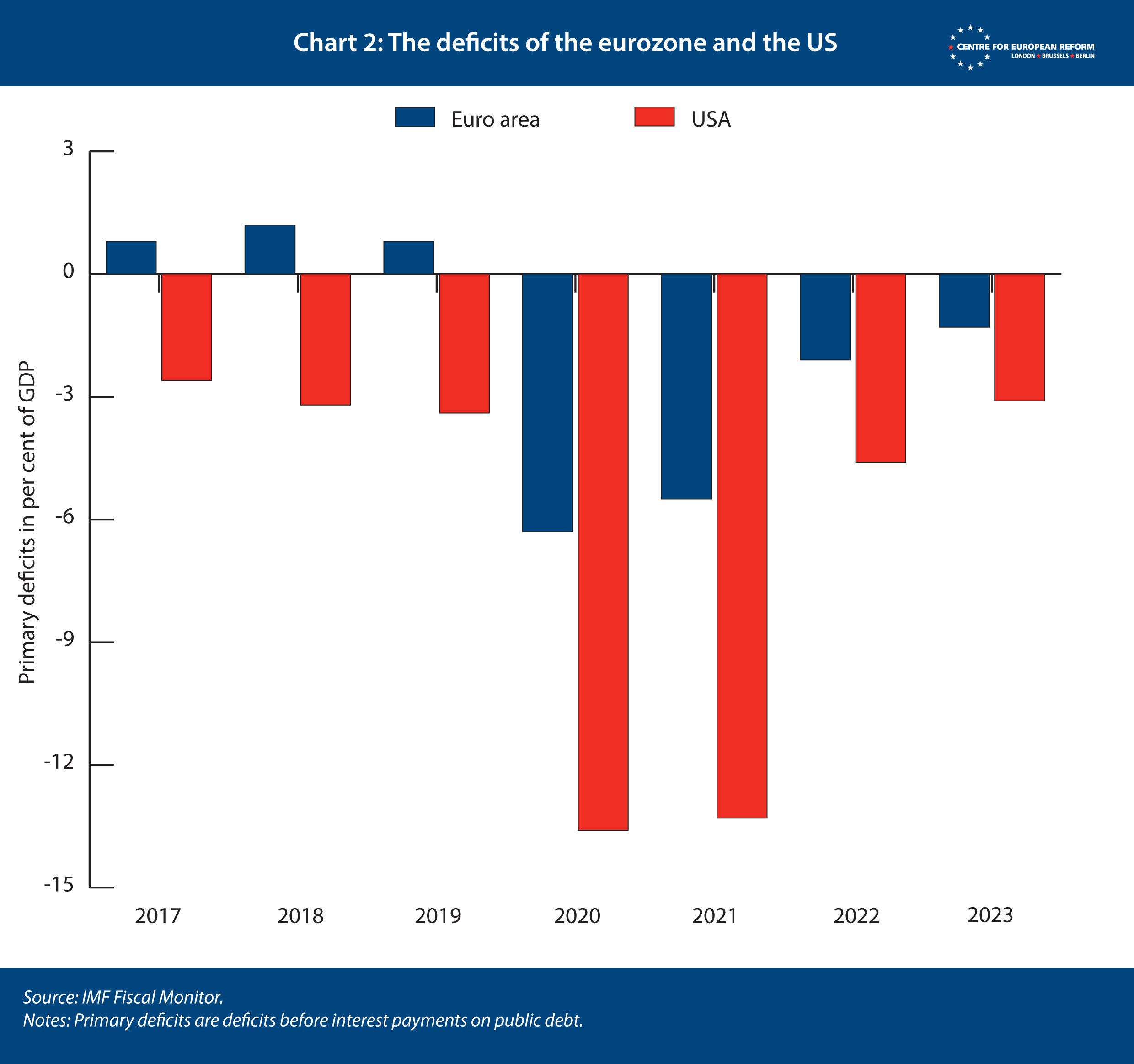

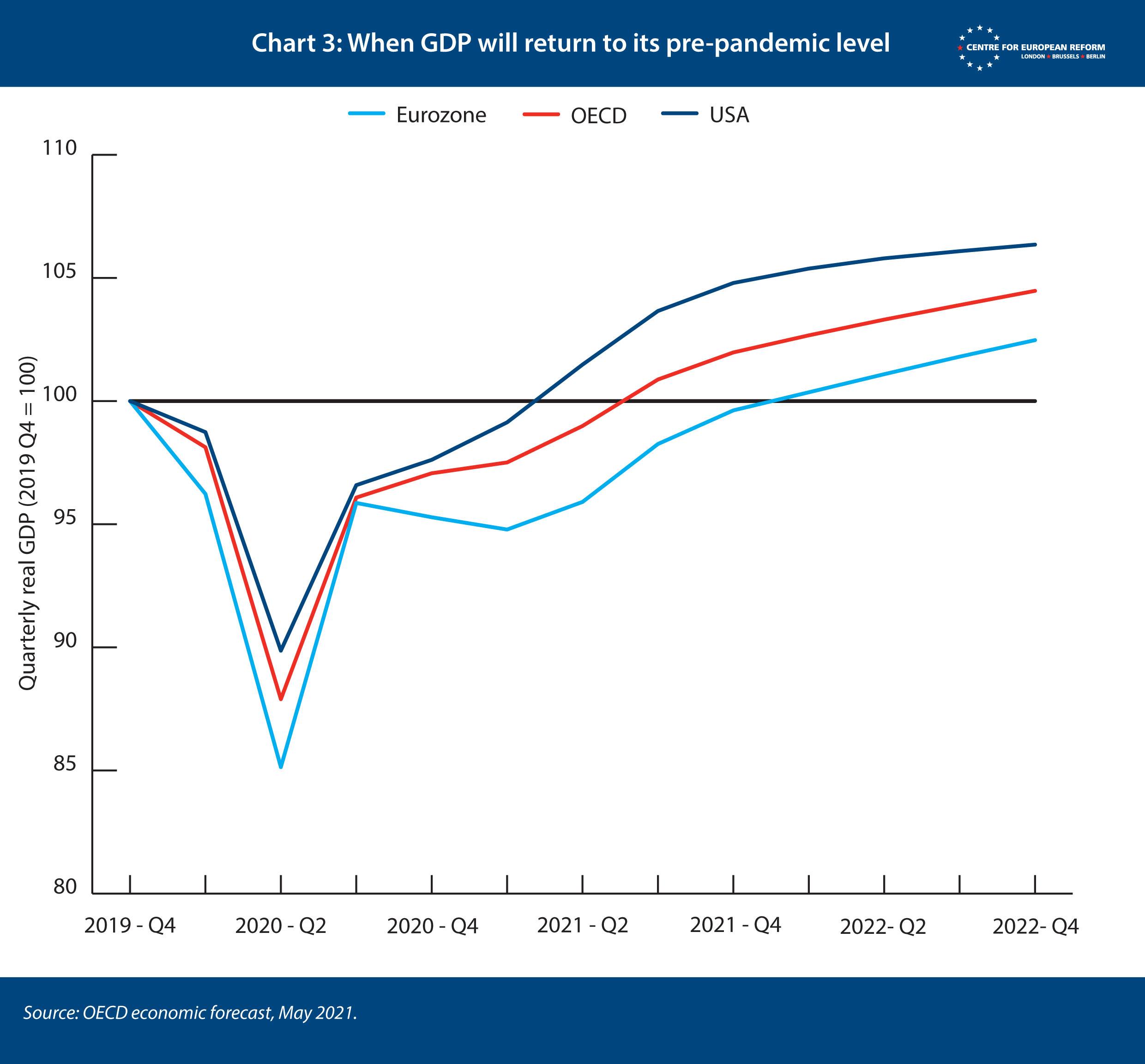

European member-states did spend to counter the pandemic and supported incomes in addition to the spending of their welfare states, which tend to be more generous than the US’s. National investment packages and the EU recovery fund will add demand over time, too. But the US was bolder in expanding its deficit to support its economy and recovery (see Chart 2) – despite being less hard hit than Europe in economic terms during the pandemic and already making a faster recovery (see Chart 3). It is thus unlikely that Europe will manage to stimulate its economy above potential.

Ingredient 2: Keep the economy over-stimulated above its potential

Over-stimulating the economy for a short while would not be enough to generate inflation that stays above 2 per cent. Policy-makers would need to keep the economy above potential for some time, in order to make people adjust their expectations of inflation, and work those into their investment plans and wage contracts.

Even though current projections deem it unlikely, the US may end up over-stimulating its economy for some time. There is a clear political commitment from the Biden administration to run a ‘high-pressure’ economy – an economy always close or even a bit above its potential – and to spend whatever it takes to get there. In Europe, on the contrary, the pressure is already on politicians to bring deficits down, even though the economy has not reached its pre-pandemic levels – which on current projections may take until 2022 (see Chart 3).

The eurozone’s current economic, fiscal and monetary setup is simply incompatible with running a high-pressure economy. It continues to run big trade surpluses, suggesting that its policy-makers value exports more than domestic demand and will resist wage increases that would threaten its export industries. Without a significant increase to wages, however, domestic consumption is bound to be sluggish. Europe’s fiscal rules and debt targets – and just as importantly, its economic narrative that makes low public debt and deficits a primary concern – all limit the extent to which fiscal policy can boost demand for a sustained period. And the ECB has mostly shown over the last decade that it sees avoiding inflation above 2 per cent as more important than ensuring full employment, even if that means running the risk of severely undershooting the inflation target. Whether the new ECB leadership is ready to tolerate somewhat higher inflation that is driven, say, by supply bottlenecks or energy prices remains to be seen (see Ingredient 5).

So even if Europe did bring its economy above potential after the pandemic, policy-makers would be unlikely to keep it there.

Ingredient 3: Throw in a few special effects to change expectations

Let us assume that European policy-makers managed to overstimulate the economy for a sustained period. Then temporary factors would help to drive some prices through the roof (at least for a while) and make people believe that higher inflation was here to stay. Such expectations matter a lot for future inflation (see Ingredient 4).

One such special effect is bottlenecks on the supply side. The pandemic has changed consumption patterns: the economy was put into a partial coma and re-awakened quickly, workers have lost jobs and are re-considering careers or have re-located, and consumers are now very keen on certain types of goods and services like travel and restaurant food. We should expect substantial supply bottlenecks when the economy starts to run on all cylinders. If firms cannot meet demand, they tend to increase prices.

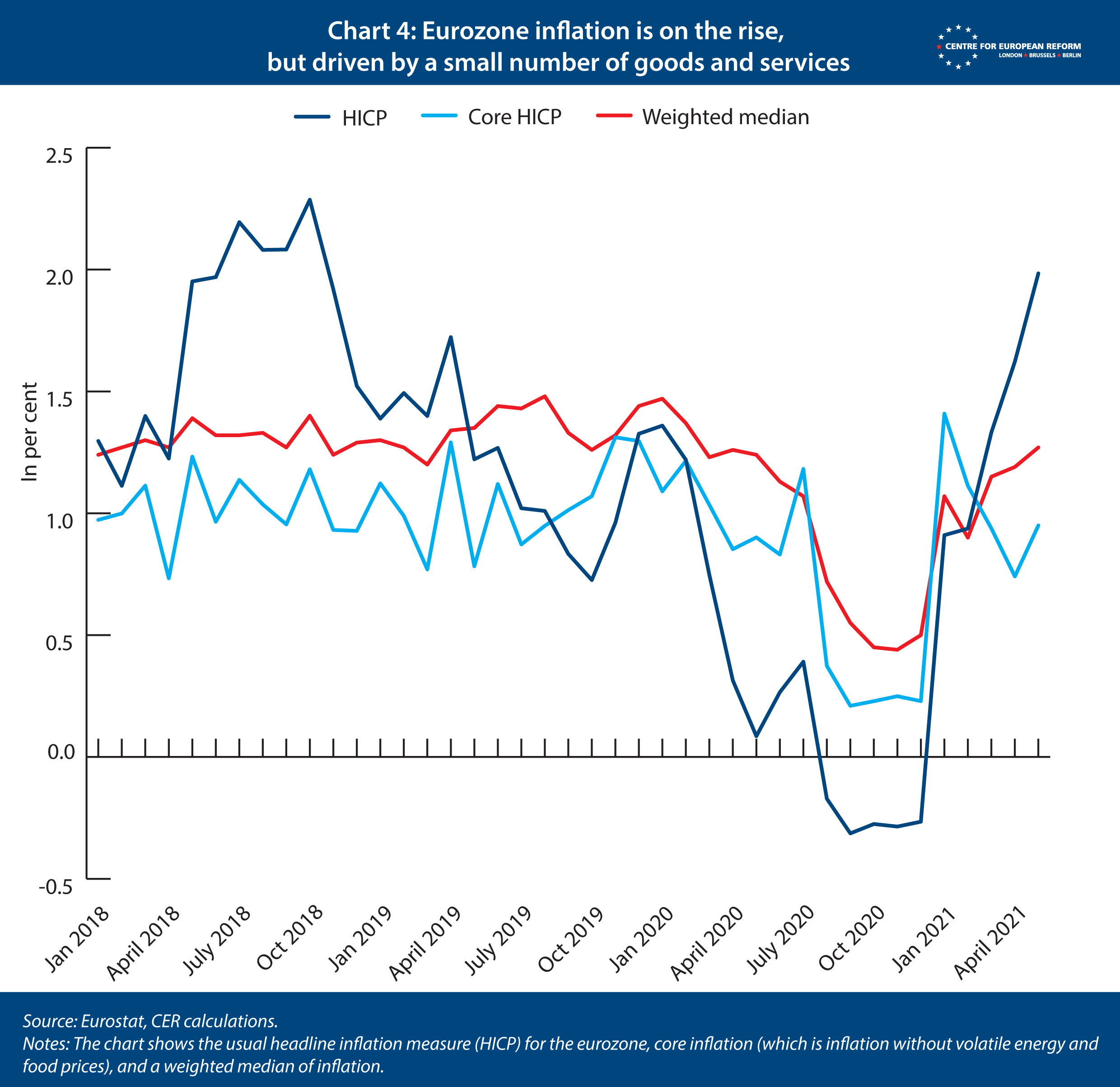

And this is what the data shows so far. Inflation has just reached 2 per cent in May (and preliminary data for June show a similar number), but that was mostly driven by ‘bottleneck’ outliers such as energy, fuel, travel and accommodation. The less volatile price indices, such as core inflation, which strips out less stable energy and food prices, are just back where they had been before. The best gauge of underlying inflation is the weighted median of price increases, that is, ranking all items in the consumer basket according to how much their price has increased, and finding the weighted middle one. That reduces the influence of goods and services with the biggest price rises or falls. Median inflation is not even back at its 2019 level, let alone above it (see Chart 4).

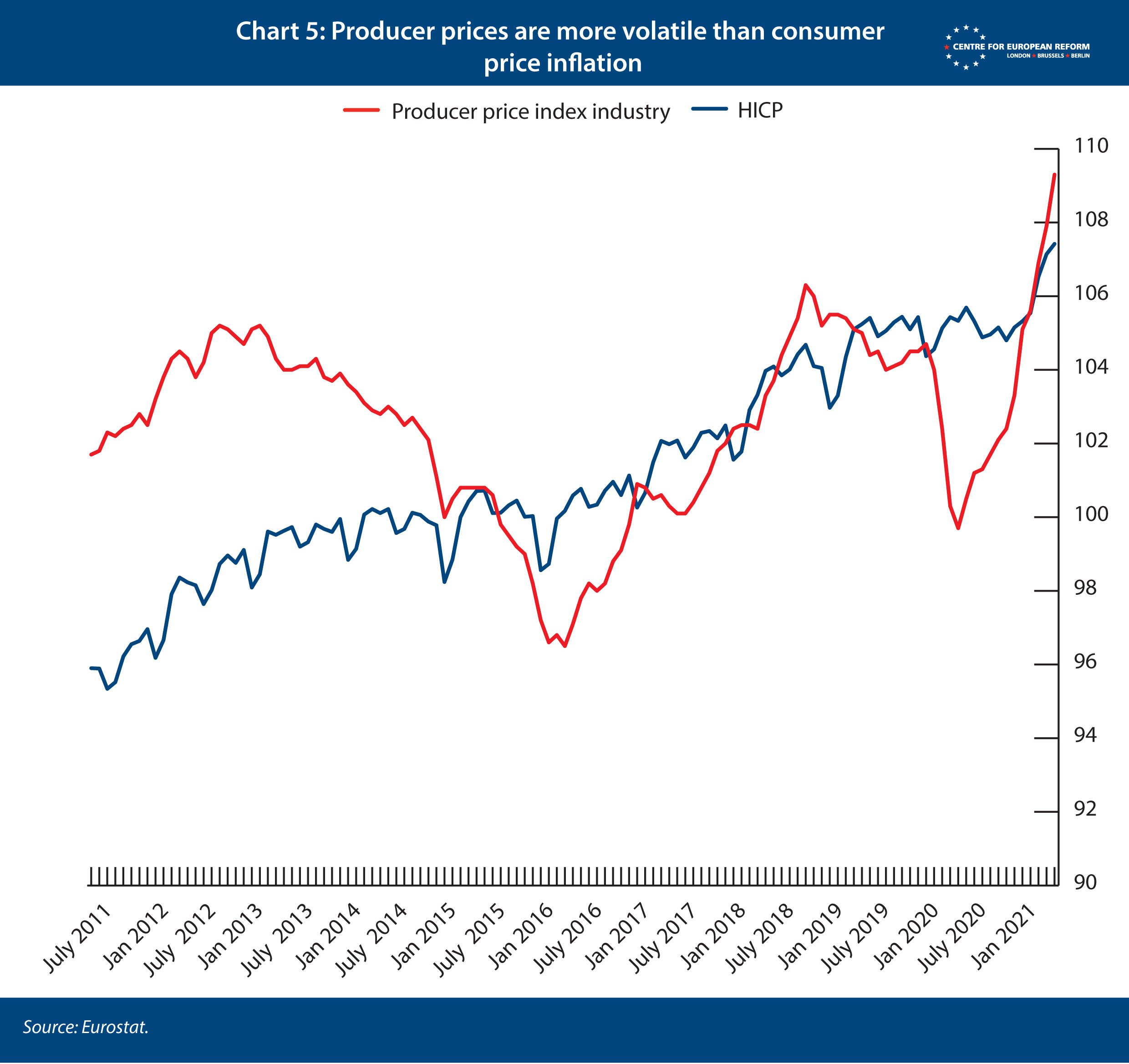

But will such supply-induced inflation be enough to make people reconsider their expectations? Industrial producer prices are a case in point. They have risen steeply, as would be expected after this pandemic. Production inputs like lumber, microchips and coffee beans, for example, have soared in price. But producer prices do not usually keep rising indefinitely (see Chart 5). A steep rise from 2016 to 2018, for example, ended abruptly when the world economy cooled. The price of lumber has already collapsed. What is more, it takes quite a bit of rising producer prices before consumer prices start to move, too. A temporary spike in producer prices is thus unlikely to provide enough inflation to change expectations.

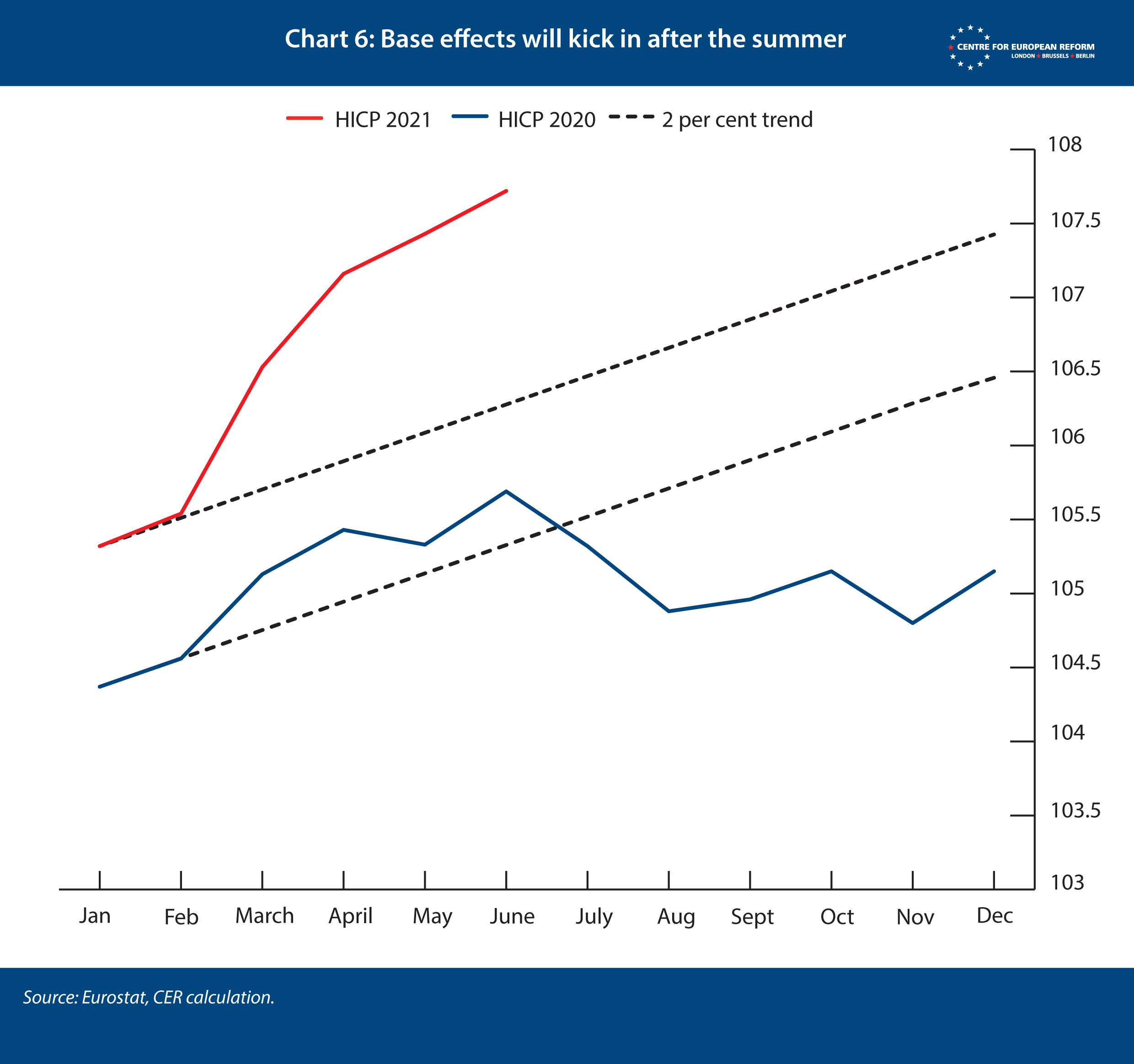

Another temporary effect is so-called ‘base effects’: when the price index from a year earlier was low for some reason, even a normal price rise a year later would yield a high inflation number. Such base effects happen all the time, but they may be especially large after this pandemic. Chart 6 shows that indeed in the second half of 2021, there will be high inflation rates because of base effects: in 2020, the consumer price index followed its roughly 2 per cent trend line until June, but then flat-lined because prices did not rise when demand was weak and temporary VAT cuts lowered prices. Inflation, which is the gap between the red and blue line, will inevitably widen considerably in the second half of this year. But most investors and many consumers are aware that base effects can affect inflation temporarily, and they are unlikely to be scared into believing that high inflation is here to stay.

Ingredient 4: Strong labour unions incorporating high inflation into labour demands

European policy-makers may thus have some of Ingredient 3, but that only works in combination with Ingredient 4, the power of labour. Inflation can only be sustained if it is incorporated into expectations, for example when wage negotiators take into account that inflation is now higher and therefore demand higher wages than they otherwise would. If wages in fact rise as a result, and companies in turn raise prices, temporarily higher inflation begets further inflation.

Is labour in Europe strong enough to demand such wage hikes? Chart 1 already shows that there is considerable untapped potential in some European labour markets. But even in supposedly tight labour markets such as Germany’s, wage increases have, so far at least, mostly been below 3 per cent a year in recent years. In part that is because firms could tap into a larger EU labour market to fill positions, and in part because workers demanded better working conditions rather than higher pay. Firms in manufacturing could also point to the competitive international environment in order to refuse sizeable pay rises.

In services industries in the private sector, labour unions do not tend to be very strong. In the ‘gig economy’, workers are usually self-employed. So even if inflation expectations edged higher, workers would struggle to swiftly turn those into higher wages. And even if employers agreed to compensation for the somewhat higher inflation of 2021, they would almost certainly make this through one-off payments, where they can, not through a general rise in wages and thus prices.

Ageing may increase the bargaining power of labour over time: demographic change, not just in Europe but also in Asia, means fewer skilled workers are available to do the complex tasks of a modern economy. Already today, some sectors in Western European countries can only thrive because workers from the East moved there. But that will not happen in time to translate any post-pandemic economic stimulus and price spikes into persistent inflation. And it may not happen at all. Europe may be able to tap into the labour markets of its wider neighbourhood and technological progress may replace many tasks that workers currently perform. A country like Japan offers a cautionary tale: it is famously closed to immigration, and its population is much older than the EU average; it also has a high employment rate (see Chart 1) and an unemployment rate of 2.4 per cent. And yet, it does not achieve wage growth worth writing about. In 2019, wages even fell for the first time in six years.

Ingredient 5: An irresponsible or politically captured central bank

Let us assume Europe managed to over-stimulate its economy for a sustained period, people expected higher inflation was here to stay, and workers’ bargaining power was strong enough to turn that into wage increases. There would still be one ingredient missing. The salt, if you will: a central bank too weak to fight excessive inflation.

The ECB’s mandate is to deliver price stability. Just recently, it updated its strategy and will now aim for a 2 per cent inflation rate, treating deviations above and below that target equally. The ECB will no longer tighten policy prematurely in order to prevent inflation rising above 2 per cent, as it previously did. Instead, the ECB will tolerate some inflation above 2 per cent in 2021 without stepping on the brakes by raising interest rates or scaling back its bond purchases.

But there is no indication that the ECB could be tempted to veer off course and let inflation and inflation expectations rise uncontested. The ECB always has the power to contain demand, for example by steeply raising interest rates. Since that power is well-established, the mere mentioning of interest rate rises by the ECB is usually enough to cool the economy. That is a reputation that the ECB has built up over the last decades, and the pandemic has not affected it.

But what if the now much higher public debt in Europe forced the ECB to tolerate inflation? The ECB has, the argument goes, bankrolled essentially insolvent governments like Italy’s. When inflation starts rising, and the economy recovers strongly, the ECB will not be able to raise interest rates as it should without sending Italy into insolvency. To prevent that, the ECB behaves irresponsibly, and lets inflation rise too high.

But that line of reasoning also falls short. First, neither higher interest rates in markets nor higher inflation fall from the sky. If both rise, it will be because of a stronger European and world economy that will also benefit Italy. Only if interest rates rose a lot more than Italy’s growth rate would Italy start to struggle.

Second, the global downward pressure on interest rates and inflation over the last four decades continues because its causes are still alive and kicking:

- high inequality in both industrialised and emerging economies, which leads to high savings because richer people tend to save more;

- ageing, which induces societies to save more to prepare for retirement;

- technological progress and global trade integration that has brought down the costs of many goods;

- a high global demand for safe assets, which the pandemic has only reinforced, that makes European public debt a prime asset for risk-averse investors; and

- still large, untapped labour markets around the world that could and will be integrated into the world economy, keeping wages and thus inflation contained.

Third, countries have used low interest rates to take on longer maturity debt. The OECD average maturity of public debt has increased from 6.3 years in 2007 to 7.7 years in 2020. Debt servicing costs have never been lower for governments, as a share of GDP – including for Italy. So even if inflation and interest rates on markets started to rise, the full effect on government deficits would be felt slowly over years, during which governments would have time to adjust if needed. (For a detailed discussion, see our recent CER policy brief on public debt.)

The #ECB will meet on Thursday to put its new strategy into practice. A fear of inflation should be left at the door.

It is true that the ECB is the final line of defence for eurozone government debt (even though the ECB could never admit that publicly). And that is a good thing: using the ECB’s ability to buy sovereign debt and manage interest on that debt as a safety valve against market panics or for the transition to a higher interest rate world is a legitimate use of a public institution in the common interest. But between today’s situation and the ECB deviating from its inflation target to stop an Italian insolvency lie a lot of assumptions: some unlikely, some heroic.

Conclusion

Getting inflation to sustainably rise above 2 per cent would be difficult, even if policy-makers wanted to. It takes all of the ingredients above, of which Europe has none. Policy-makers are right to be relaxed: the somewhat higher inflation in the second half of 2021 will be temporary and should not distract them from achieving a rapid and full recovery from this pandemic. Policy-makers should even welcome strong wage growth, if it happens, to make up for the shortfall in the last decade. They should use that opportunity to keep inflation up at 2 per cent, and not let it slip below target again, as the ECB is currently projecting. After securing a consensus on the ECB’s new strategy, ECB president Christine Lagarde should be bold in seeing it implemented.

Christian Odendahl is chief economist at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment