The Ukraine Reparations Loan: How to fix Europe's financial plumbing

As US support for Ukraine vanishes, Europe must overcome Belgian opposition and improvise fiscally to provide Kyiv with €210 billion.

The new US National Security Strategy and the Russia-friendly proposals given to Moscow by Steve Witkoff, US President Donald Trump’s all-purpose ‘peace’ envoy, for ending the war in Ukraine have sent a clear message to Kyiv – and Europe. Whatever security guarantees it offers, sooner or later the Trump administration will abandon Ukraine.

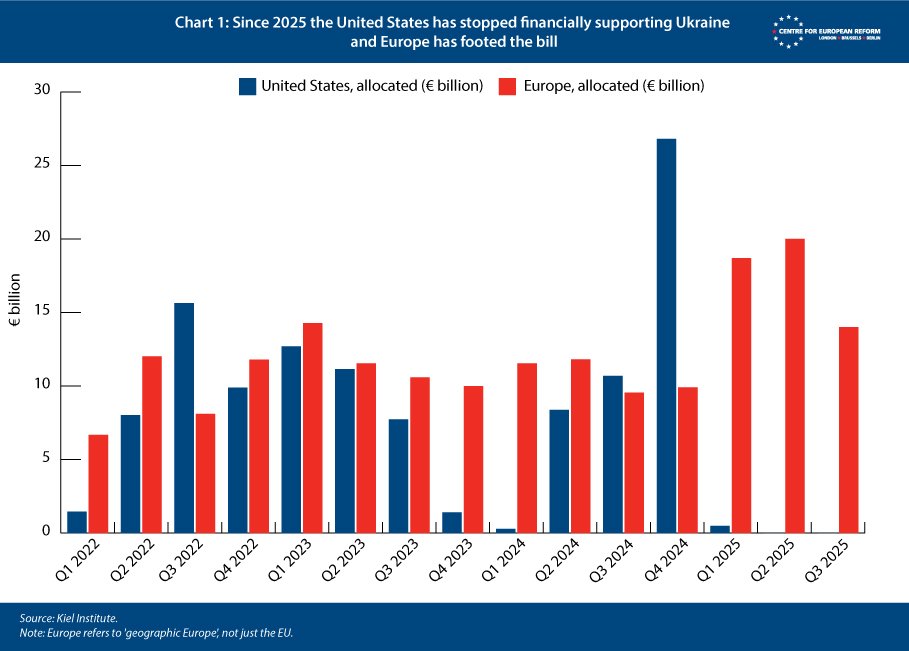

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, the US has been Ukraine’s biggest individual donor – allocating €114.63 billion in military, financial, and humanitarian aid since 2022, according to the Kiel Institute (see Chart 1). It is nearly twice as much as the EU’s €69.6 billion, more than five times Germany’s €22.49 billion, and nearly seventeen times France’s €6.76 billion – although it lags the cumulative €161.36 billion from the EU and its member-states. Ukraine now needs €135 billion in funding for 2026–2027 alone and there are few easy ways to raise it without a US contribution.

EU leaders are struggling to unlock a €210 billion ‘reparations loan’ to Ukraine by the time they meet on December 18th-19th, using the Russian Central Bank’s immobilised assets – after Washington’s peace plan suggested that the US and Russia would decide how to use these assets. In addition to financing Ukraine for the next year, the European Council meeting will probably initiate a debate on how to deploy more of Russia’s assets for Ukraine and related policy priorities.

If EU leaders fail to agree on the reparations loan, there is no obvious alternative. EU common borrowing to provide extra funds for Ukraine would require unanimity (which remains elusive), as would changing the rules of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) – the eurozone bailout fund– to fund an external partner. Bilateral loans from member-states would increase their debt levels to provide Ukraine with funding. The reparations loan’s design, however, avoids an immediate rise in member-states’ debt, and keeps outcomes contingent on the course of the war and eventual Russian reparations.

The Reparations Loan: How it works

The Commission has proposed that the reparations loan should take the form of a zero-coupon (interest-free) loan of up to $210 billion to Ukraine. Those financial institutions where Russian assets are frozen (now mainly cash balances) would lend €210 billion to the Commission, which would in turn lend it to Ukraine. This would be a ‘limited recourse loan’, which means it would only be repaid if Ukraine received equal reparations from Russia. Those reparations would allow the frozen assets to be returned to the Central Bank of Russia (CBR).

The €210 billion would comprise three elements:

- The bulk – €115 billion – would be dedicated to integrating Ukraine’s defence industry into Europe’s and expanding its manufacturing capacity. The Commission’s plan also includes a ‘Buy European & Ukrainian’ provision: the cost of components originating outside the EU, EEA EFTA, and Ukraine could not constitute more than 35 per cent of the total.

- A further €50 billion in macro-financial assistance would provide direct budget assistance and cover Ukraine’s financing gap.

- Finally, €45 billion would be used to repay the G7’s ‘Extraordinary Revenue Acceleration’ (ERA) loan to Ukraine, fulfilling a G7 agreement to repay the ERA from revenues generated by immobilised Russian assets.

Belgium’s concerns

The majority of Russia’s frozen assets – €193 billion – are held by Euroclear, a central securities depository based in Belgium. In 2025, Russian assets at Euroclear generated €3.9 billion in interest earnings, 25 per cent lower than the prior year, because of ECB rate cuts. The EU’s ‘windfall contribution’ regulation required Euroclear to transfer €2.6 billion of this to the European Commission. The Commission’s plan would tap into the assets themselves rather than just the interest earnings for the first time.

The reparations loan would be backed by frozen Russian assets beyond those in Euroclear – such as approximately €18 billion of Russian assets in France. The exceptionally large exposure of Euroclear worries Belgium, however. Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever has expressed concern that the sanctions regime underpinning the reparations loan may collapse, triggering premature repayment for which Euroclear may lack the cash; that Russia will sue Belgium under a bilateral investment treaty and win its assets back; or that the eventual resolution of the war will not require Russia to make a full reparations payment to Ukraine. For this reason, De Wever has demanded political, legal, and financial guarantees. As we discuss below, there are contractual, regulatory, and legal reasons, however, why Euroclear would not enter into default. These should take the pressure off Euroclear, Belgium, and future designs to use frozen Russian assets.

Legal concerns

Last week the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) announced that it was suing Euroclear. The case was filed with the Moscow Court of Arbitration. The fact that CBR filed the case here shows that Russia’s case against Euroclear and Belgium is weak. The Moscow Court of Arbitration has no capacity to recoup Russian seized assets.

If Russia had a robust case, it could take Euroclear and Belgium to arbitration under the Belgium-Luxembourg-USSR Bilateral Investment Treaty of 1989. This treaty has nominally been the source of Belgium’s legal concerns. But those concerns seem ill-founded. The treaty stipulates that any case would be held either at the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce or the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). Russia, however, does not accept the jurisdiction of either body.

The last time a Russian entity faced arbitration before the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (Uniper v. Gazprom 2024), it did not appoint an arbitrator, honour the arbitration award, or issue a post-award statement. Gazprom’s comments were limited to rejecting the tribunal’s authority. The last time a case involving Russia went before UNCITRAL (Krymenergo v Russia 2025), Russia similarly argued that the tribunal “did not have jurisdiction to hear the dispute.” It went on to lose both cases. In any case, the legal risk here would have arisen in 2022, when Belgium and Euroclear immobilised the CBR’s assets in compliance with EU sanctions.

To the extent that legal concerns still exist, Belgium and other EU countries can further insulate themselves from lawsuits by withdrawing from any relevant treaties, as Ursula von der Leyen has proposed. The EU and the member-states can also do more work to pass legislation that insulates countries from potential legal concerns by specifically authorising the immobilisation of sovereign assets and prohibiting the return of assets that would finance the illegal invasion of a third country.

Liquidity concerns

Belgium was also worried that if a problem occurred, EU member-states would be unable to immediately honour their guarantees. That would push Euroclear into default and enable the CBR to pursue Euroclear’s assets. For this reason, Prime Minister De Wever called for financial guarantees to Euroclear to be available ‘on demand’.

His assumption seems to be that EU member-states would be blindsided by a negative event – such as a court ruling, the collapse of the sanctions regime underpinning the reparations loan, or a resolution to the war that did not require Russia to pay full reparations – and that the member-states would tap markets en masse to raise €210 billion all at once. Countries could pre-fund part of their guarantees to allay this concern; but in any case it is unlikely that such an important event would come as a surprise, enabling EU member-states to scale up the funding of their guarantees in advance.

The liquidity concern is overblown for more material reasons. Euroclear would benefit from contractual, regulatory, and legal buffer periods before having to return assets to the CBR.

- The contractual buffer is that Euroclear would have an easy force majeure claim – a standard operating procedure for financial institutions – that would contractually excuse a temporary payment delay until guarantees were honoured.

- The regulatory buffer is that under Article 178 of the EU Capital Requirements Regulation, a default is only registered if ‘the obligor is past due more than 90 days on any material credit obligation’. This means that Euroclear would have three months for its guarantors to pay up before it technically entered into default.

- The legal buffer is that under Belgian law – Book XX of the Belgian Code of Economic Law – a Belgian entity is only legally in bankruptcy when two conditions are met simultaneously. The entity must be in a state of ‘persistent cessation of payment’ (être en cessation de paiement persistant) and in a ‘credit crisis’ (être en ébranlement de credit). It is highly unlikely that either condition would be met. Euroclear will remain current on all liabilities except those subject to EU sanctions. Its cessation of payments cannot be described as ‘persistent’. Euroclear would be temporarily illiquid rather than insolvent: guarantees from other EU member-states and perhaps the European Investment Bank (EIB) would be registered as a contingent asset greater than or equal to Euroclear’s liability to the CBR. This would make it eligible for Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) from a national central bank, so Euroclear would not enter default under Belgian law. Moreover, a liquidity crunch simply due to a delay in governments honouring guarantees would be obvious to markets, probably enabling Euroclear to continue raising funding from capital markets.

The indefinite freeze on Russian assets

Last week, the EU took an extraordinary step to remove internal political risks from the reparations loan plan – which should also have greatly reduced Belgium’s concerns. It used Article 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to freeze the €210 billion of CBR assets permanently, by qualified majority voting.

Article 122 states: “The Council, on a proposal from the Commission, may decide, in a spirit of solidarity between Member States, upon the measures appropriate to the economic situation…”. Using Article 122 prevents a single member-state from vetoing the measure. Previously, sanctions on Russia (including the immobilisation of CBR assets) had to be reauthorised every six months. This created the recurring risk that Moscow-leaning Hungary or Slovakia would veto sanctions reauthorisation, and Euroclear would be obliged to return Russian sovereign assets that it had lent out to Ukraine (via the Commission).

The use of Article 122 to eliminate these risks is novel but appears robust. The Commission’s explanatory memorandum makes two strong arguments linking the immobilisation of Russian assets to Article 122’s economic remit.

First, the Commission observes that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has had a clear economic impact on the EU and that Russia’s ability to continue the war will continue to generate ‘significant direct fiscal costs’ for member-states. An extra €210 billion would certainly contribute to Russia’s war effort, so there is an obvious urgency to ensuring that those assets are not returned.

Second, the Commission notes that member-states’ continuing need to support Ukraine ”constitutes an important economic challenge.” This is clearly true. Direct fiscal funding of €210 billion to finance Ukraine would put serious pressure on EU member-states. Ensuring that cash balances remain in place to fund the reparations loan is therefore a fiscal necessity, tying it to Article 122’s core mandate. The Commission observes that it is “therefore inextricably linked to mitigating the serious economic consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.”

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has indicated that Hungary may initiate legal proceedings against this use of Article 122. The expansion of Article 122 as a crisis legal basis is not uncontested: the European Parliament is testing it in a pending case on its use for the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) defence lending programme. Still, the Court has traditionally afforded the EU institutions wide discretion in emergency contexts, and in any event the Commission’s approach buys the Union critical time. Credit rating agency Fitch put Euroclear on negative watch without downgrading it, reflecting concerns about liquidity risk. Other credit rating agencies have not done this for good reason. The assets in question are indefinitely frozen – meaning the associated liquidity risk of an unexpected unfreezing has been eliminated – and in the off chance this were still to occur the Commission has lined up multiple layers of guarantees to provide liquidity.

The quest for national guarantees and the EIB option

Even with the CBR assets permanently frozen, the reparations loan could not proceed without national backstops. The loan would be financed by forcing Euroclear and other central security depositories to reinvest the cash balances generated by the frozen CBR assets into an EU debt instrument. But those assets remain the property of the Russian state. If, at some future point, sanctions are lifted, or if Russia successfully challenges the measures in court, Euroclear and Belgium could be exposed to a repayment claim.

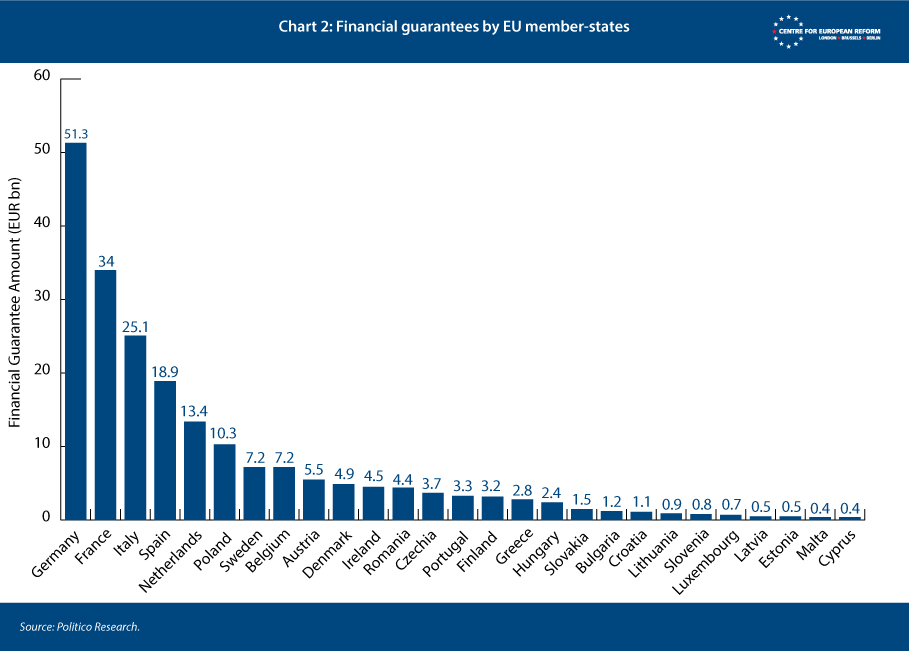

To ensure that Belgium is not left carrying the liability alone, the Commission proposes a system of member-state guarantees (see Chart 2). These guarantees, totalling €210 billion, would be divided proportionally across the EU according to a country’s share of EU GNI, with Germany covering 24.4 per cent of any potential losses (€51.3 billion). France’s obligation would be €34 billion, Italy’s €25.1 billion, and Spain’s €18.9 billion.

These guarantees would function as a collective insurance pool. They should reassure Belgium that if the assets were unfrozen for any reason, the entire financial burden would be shared across the Union. Defections could leave a material gap in Belgium’s guarantee coverage, however. Hungary and Slovakia are unlikely to provide their €2.4 billion or €1.5 billion respectively. Czechia’s Prime Minister Andrej Babiš has also rejected the proposal, which would involve Czechia providing €3.7 billion. Bulgaria and Malta, responsible for €1.2 billion and €400 million respectively, have also called for alternatives to the reparations loan.

The list of current defectors would create a €9.2 billion hole in the guarantee architecture. Italy’s governing parties have also expressed reservations about the plan, potentially adding €25.1 billion to the gap. Fortunately, the EU has another readily available option for plugging the hole in the form of the EIB.

The EIB, the official multilateral development bank (MDB) of the EU and the largest in the world, is flexible in what it can offer: direct sovereign lending, guarantees, debt and equity financing for private firms, fund investments, and the like. In 2022 shareholders established ‘EIB Global’ to lend beyond the EU. But the EIB’s financing to Ukraine has been small, totalling just €4 billion since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, as of November 2025. The EIB has chronically under-utilised its balance sheet and is now sitting on €190 billion in spare financing capacity. This is primarily because the EIB, unlike other MDBs, has stagnated its lending over the past decade. EIB lending has stagnated over the past decade. While the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s (IBRD) has increased financing by 71 per cent, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) by 73 per cent, EIB lending has grown by just 1.5 per cent.

The EIB has the financing capacity and, via EIB Global, the mandate to guarantee an obligation of Ukraine, such as the reparations loan. There is a clean and cost-free way to do this, mirroring how other MDBs use their excess cash, which they tend to dedicate to important priorities. At present, all the EIB’s profit at the end of the year flows back into its equity base, leaving the bank with €58 billion in excess cash, which banks like the EIB can leverage to loan out a much higher sum. A small portion of this could easily be allocated internally as a guarantee against EIB Global’s exposure. The EIB could then cover any gaps in guarantees left by the defections of member-states. The use of the EIB route has become less urgent since the Commission used Article 122. But even post-Article 122 the underlying mechanics can fill gaps in the architecture to support the reparations loan, and the EIB’s €190 billion in balance sheet capacity could be crucial more broadly in supporting Ukraine in the future.

Conclusion

The Ukraine reparations loan is not a legal curiosity or a fiscal sleight of hand; it is a test of Europe’s ability to take essential action when traditional tools fail. By mobilising frozen Russian assets, navigating entirely manageable legal risks, and using Article 122 to overcome veto threats, the EU has assembled a workable prototype for large-scale foreign policy financing without overburdening national budgets. National guarantees can shore up the funding, while the EIB’s underused balance sheet offers a credible backstop if some member-states fail to do their share. If the EU can make this mechanism work, it will have done more than keep Ukraine in the fight: in a more contested world, it will have hardened the fiscal-financial plumbing needed to protect itself in crises to come.

Stephen Paduano is a postdoctoral fellow at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford and an economist at the Finance for Development Lab.

Sander Tordoir is chief economist at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment