The ECB's bid to strengthen the euro's global role

As dollar dominance wobbles, Europe should boost the euro’s reach, led by bolder liquidity lines from the ECB.

Europe and the dollar jitters

The dollar, long seen as the ultimate safe haven, recorded one of its sharpest declines since the 1970s in April last year. After President Donald Trump announced his ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs, the S&P 500 fell by around 12 per cent, the dollar weakened by roughly 6 per cent, and long-term US interest rates rose – an unusual simultaneous decline across American asset classes.

Large long-term investors have remained cautious since then. Danish and Dutch pension funds recently reduced their holdings of US government bonds, spurred on by US threats towards Greenland’s territorial integrity. Much of the pressure on the dollar reflects currency hedging rather than outright sales, but it signals that high portfolio concentration in US assets is becoming a concern, given the political risks, including to the independence of the US central bank.

Globally, the dollar system is beginning to fray. Russia, India and China are increasingly settling trade, especially commodities, in their own currencies to circumvent US sanctions, while central banks continue to buy gold. Above all, investors are growing less confident in the predictability of US policy and institutions.

Globally, the dollar system is beginning to fray …investors are growing less confident in the predictability of US policy and institutions.

All this is prompting investors to question an old assumption: that the US – and therefore the dollar – will always provide the stable centre of the global financial system. This creates a strategic opportunity for Europe. Strengthening the international role of the euro could generate structurally higher demand for European assets and allow capital to be raised more cheaply, including for defence spending and other forms of ‘strategic autonomy’.

But Europe also faces risks: the euro’s current role as a distant second to the dollar is not unassailable. It could yet lose ground to the dollar, for example if dollar-denominated stablecoins encourage digital dollarisation. And the renminbi could challenge the euro, as China increasingly uses its prowess in global trade to promote the international role of its currency.

Europe lacks the consolidated capital markets, institutional coherence and supply of safe assets that underpin a truly dominant currency, and much of the necessary work lies beyond monetary policy. But as the global financial order becomes more contested, the actions of the European Central Bank (ECB) will determine whether, how far, and how fast, the euro’s international role can expand.

Europe lacks the consolidated capital markets, institutional coherence and supply of safe assets that underpin a truly dominant currency.

At last week’s Munich Security Conference, ECB President Christine Lagarde announced that the bank will make its euro repo lines permanently available to central banks worldwide from 2026 – a choice of venue underscoring the geopolitical context of the move. Repo lines allow foreign central banks to access euros against collateral. By converting them from a discretionary emergency instrument to a standing facility in principle open to all central banks, the ECB is signalling a more strategic approach to supporting global euro funding markets.

The ECB’s shift is timely and necessary, but also insufficient. The ECB can capitalise on favourable tailwinds. EU member-states are ramping up defence spending – if the EU can provide more safety, it would support demand for euro-denominated assets from allies. The EU also remains a relatively stable anchor of central bank independence and the rule of law. But the euro’s structural weaknesses mean progress will not happen automatically. The ECB’s liquidity lines are among the few instruments capable of delivering near-term gains, but only if they are expanded more deliberately and at greater scale.

Geopolitical power

The international role of a currency ultimately rests on three pillars: first, geopolitical power and security; second, strong institutions and the rule of law; third, economic scale, liquidity and well-functioning financial markets. If a currency lacks any one of these pillars, it cannot dominate internationally.

That power and money are intertwined is not a new insight. The British pound lost its central role when the UK’s geopolitical dominance faded. Today, too, geopolitical power and monetary status remain closely linked. And it is precisely on that first point – power and security – that Europe is changing rapidly. Joint European defence spending now stands at around €380 billion per year and is heading towards roughly €650 billion, and even €800 billion if you add in the non-EU European NATO countries. By around 2028, McKinsey expects NATO Europe to spend more on military equipment than the US currently does.

Historical research by Barry Eichengreen, Livia Chitu and Arnaud Mehl shows that security guarantees and military alliances can raise a currency’s share in allies’ foreign reserves by almost 30 percentage points. A Europe capable of organising its own security, and extending it to others, would also be taken more seriously as a financial anchor. Allied countries, from Canada and Japan to Turkey, would hold more euro reserves in such a world.

A Europe capable of organising its own security, and extending it to others, would also be taken more seriously as a financial anchor.

The second pillar, institutions and rule of law, is where a stark contrast with the US has emerged. The dollar’s international appeal has always been based on the combination of America’s large, open capital market and the predictability of its system: an independent central bank, stable, rules-based policies, and a government that respects contracts and property rights.

Yet these certainties are under pressure. Trump has openly attacked the independence of the Federal Reserve and has allowed prosecutors to investigate chair Jerome Powell and board member Lisa Cook. It is unclear whether prospective new Fed chair Kevin Warsh would act as an independent central banker or as Trump’s loyal servant. The Fed risks being drawn explicitly into the political arena, raising the spectre of fiscal dominance – monetary policy increasingly determined by the need to finance the government cheaply, historically often resulting in high inflation.

Meanwhile, US economic policy is becoming more arbitrary: ad-hoc tariff exemptions for individual companies, trade policy that shifts from month to month, and even sudden interventions such as halting nearly completed offshore wind projects, challenging as fundamental a principle as property rights.

For an international currency, this is highly damaging. By contrast, the eurozone has the ECB, one of the most independent central banks in the world. And if there is one thing the European Union certainly is, it is a predictable legal order.

The euro’s underlying weaknesses

The euro’s Achilles heel is the lack of a deep capital market. Central banks hold foreign exchange reserves – usually in the form of government bonds such as US Treasuries – to stabilise their currencies during financial shocks. The world cannot simply convert existing dollar reserves, which run into the trillions, into euros. The supply of safe European government bonds is too limited. In the EU, highly-rated sovereign debt amounts to less than 50 per cent of GDP, compared with over 100 per cent in the US.

The world cannot simply convert existing dollar reserves, which run into the trillions, into euros. The supply of safe European government bonds is too limited.

But this is beginning to shift. Germany, with its high credit rating, will issue significantly more debt in the coming years, with its debt ratio potentially rising towards 80 per cent of GDP. That would put a lot more euro-denominated safe assets into the market. In addition, more than €1.4 trillion in joint European debt is now outstanding thanks to borrowing by the European Commission, the European Investment Bank and the European Stability Mechanism.

That EU supranational debt is in demand is clear from its small yield premium over German government bonds. New joint spending on defence and strategic investments, such as European satellites to reduce reliance on systems like Starlink, owned by Elon Musk, is on the table too.

What is less of a barrier is that the eurozone runs a current-account surplus: it lends to the rest of the world rather than attracting foreign savings. But, historically, the UK and US still managed to internationalise their currencies while running surpluses by recycling them into foreign assets in sterling or dollars rather than importing more goods (As Karthik Sankaran notes, this is a possible pathway for China, with its supersized surpluses, to internationalise the renminbi).

Unfortunately, the EU’s capital markets union is progressing far too slowly. Whether EU leaders are willing to give up national sovereignty to truly integrate capital markets – integrating supervision, shuttering regional stock markets and aligning corporate insolvency and securities law, remains very much in question.

What is already changing in Europe is the ECB’s stance. Where it once remained neutral towards the euro’s international role, it has since 2019 officially committed to strengthening it.

The price of stronger euro demand is a structurally higher exchange rate, which would dampen European exports. In the short term, this could potentially be mitigated by an appropriate monetary policy such as ECB rate cuts, as the stronger euro reduces imported inflationary pressures. The benefit of euro internationalisation would be lower interest rates, and stronger internal demand would be beneficial as Europe’s export-led growth model is being eroded by China’s export surge and US tariffs.

The price of stronger euro demand is a structurally higher exchange rate, which would dampen European exports.

The ECB’s liquidity lines

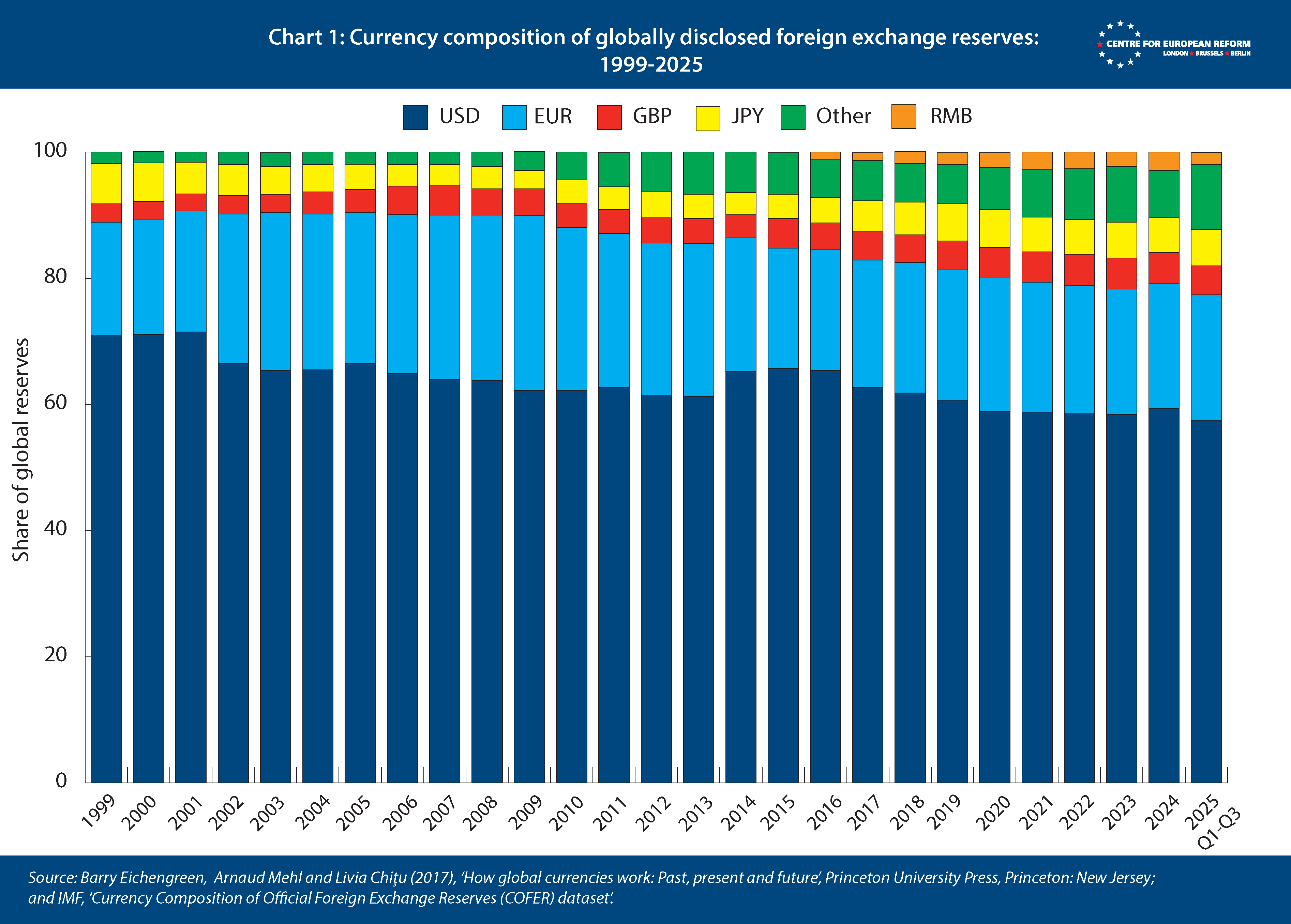

Resting on the three pillars above (geopolitical power; the rule of law; and large and liquid capital markets), a truly dominant currency will be significant across several economic functions. For example: as a currency in which central banks hold foreign exchange reserves; as a currency in which debt securities are issued internationally and bank loans are granted; and as a currency in which global payments are made and trade is invoiced. What is more, these functions are mutually reinforcing and can create powerful network effects. Across such metrics, the euro is currently the second-largest international currency (see Chart 1). A credible strategy for the international role of the euro would have to span all dimensions of an international currency’s role.

The ECB’s liquidity lines with foreign central banks are an essential component of any such strategy. By providing euro liquidity to other monetary authorities, the ECB makes the international availability of euro funds more reliable, strengthening the common currency’s role in cross-border banking and finance. In turn, this can boost the euro’s use for ‘real economy’ transactions such as international trade and remittances.

The ECB’s announcement last weekend is therefore a major positive step. By extending the euro liquidity-providing repo facility (EUREP) it will strengthen the international role of the euro. This shows that geopolitical considerations increasingly shape the ECB’s actions.

However, the ECB can do far more with its international liquidity provision tools to strengthen the international role of the euro.

The euro’s near abroad. The internationalisation of the euro should start in the eurozone’s immediate neighbourhood, which is most economically and politically integrated with it.

- While making EUREP globally available in principle is a necessary first step, the ECB and European diplomacy may need to actively pursue the establishment of these lines beyond the existing ones with European microstates and Western Balkan EU accession candidates. For example, the use of the euro in countries of its southern neighbourhood is, on average, higher than in the rest of the world. In the Maghreb countries, the euro even plays a more important role than the dollar.

- The ECB should offer swap lines with the central banks of all EU member-states that have not adopted the euro (in a swap line, the ECB lends euro against the receiving central bank’s currency, rather than euro-denominated collateral, as in the case of EUREP). This would involve upgrading existing repo lines with the central banks of Hungary and Romania to swap lines. Because of their more precarious geopolitical situation, Ukraine and Moldova could be offered swap lines ahead of official EU membership as soon as this is feasible.

The global euro. Beyond Europe’s immediate geographic vicinity, recent geopolitical tensions and the resurgence of protectionism with major trading partners have provided new impetus for intensifying the EU’s trade relations with other major economies and blocs – most recently, South America’s Mercosur, and India. Such closer partnerships are also an opportunity to advance the international role of the euro. The ECB should therefore:

- Expand its network of swap lines to the central banks of the Mercosur countries, the Reserve Bank of India, and potentially the central banks of other major global trading partners that are not already covered by such agreements. Currently, the ECB operates a network of reciprocal swap lines with globally systemic advanced economies (the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the Federal Reserve and the Swiss National Bank); and has agreements to provide euro to Sweden’s Riksbank, Denmark’s National Bank, and the People’s Bank of China.

The ECB should not use its balance sheet – via its swap lines – as a financial assistance mechanism for foreign countries, as seems to be the case with some of the swap lines of the People’s Bank of China. We are merely proposing that the ECB enters into standard agreements with a larger set of central banks. Since the terms of those agreements protect central banks from financial losses, any additional risk is at most marginal.

Provision of a global public good. By making euro funding more widely available internationally, the ECB would also contribute towards the provision of a public good: global financial stability. In times of financial market turbulence, demand for international liquidity – particularly for the US dollar as the dominant currency – soars. This demand is satisfied mostly through liquidity provision by the US Federal Reserve via swap lines with other central banks. However, the Trump administration’s repudiation of US global leadership means it is prudent to no longer take for granted the Fed’s role as global lender of last resort. The ECB should be ready to take on the responsibility for the stewardship of the global financial system that comes with Europe’s desired role for the euro.

Legal mandate. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and the Statute of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) grant broad legal authority to the ECB to enter into these agreements. To the extent that any additional financial risk would appear to be relevant for the ECB’s financial strength, the ECB could invoke Article 127(1) TFEU, which allows it to support the general economic policies of the EU as long as price stability is not jeopardised. The ECB has invoked this article to justify policies to counter the risks from climate change.

Conclusion

Euro internationalisation matters. The larger the euro’s role in the global financial system, the greater the structural demand for European assets, and the lower financing costs for European governments and companies. That makes it easier to invest in defence, strategic industries and the green transition. Monetary power is not a prestige project but a productive asset.

The larger the euro’s role in the global financial system, the greater the structural demand for European assets, and the lower financing costs for European governments and companies.

What is more, a greater systemic role for the euro acts as a geopolitical shield. The US can enforce sanctions by restricting access to dollar clearing and the wider international financial system. Reducing reliance on the dollar would make Europe less vulnerable, should transatlantic relations deteriorate further.

The world is not on the verge of a rapid change of throne in currency dominance. The euro will not replace the dollar, and nor will China’s renminbi: China faces too many self-imposed constraints, including capital controls, a relatively small bond market and a government that does not always respect private property rights.

But the currency world is becoming less monolithic, and the dollar’s role as global anchor is no longer guaranteed. In that environment, the ECB’s liquidity framework becomes strategically important. By expanding and institutionalising its euro liquidity lines, the ECB can help translate shifting global conditions into lasting demand for euro assets – and ensure that Europe captures a larger role in a less dollar-centred system.

Spyros Andreopoulos runs the consultancy Thin Ice Macroeconomics and Sander Tordoir is chief economist at the CER. Both are former ECB economists.

Add new comment