UK foreign and security policy after Brexit

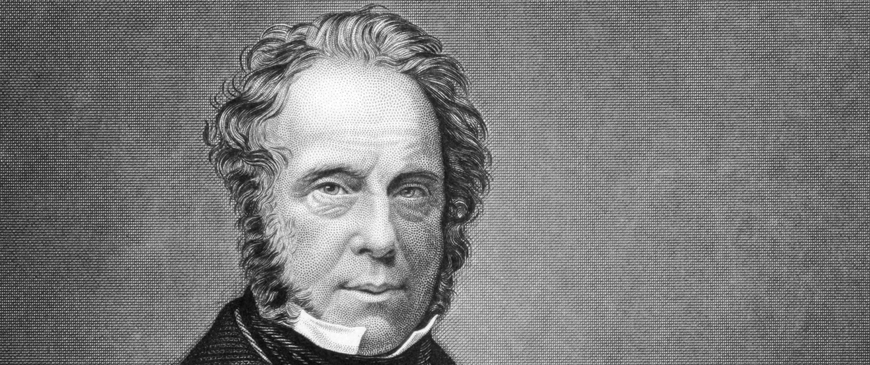

Nobody works in the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office for long without hearing the dictum of 19th century Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston: “We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow”. Palmerston may have treated Britain’s relations with other states as ephemeral, but from the beginning of the Cold War until the Brexit referendum, the UK treated the preservation of its alliances as one of its perpetual interests.

In December 2019, however, the British government announced an ‘integrated security defence and foreign policy review’ that will “reassess the nation’s place in the world, covering all aspects of international policy from defence to diplomacy and development”. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that this would be the deepest review since the end of the Cold War – implying that it might lead to a radical reshaping of the UK’s approach to its relations with other European powers.

The UK government has announced an ‘integrated security defence and foreign policy review’ “to reassess the nation’s place in the world”. Boris Johnson said that this would be the deepest review since the end of the Cold War.

When she was prime minister, Theresa May shied away from any drastic change in foreign and security policy relations with the EU. The government’s July 2018 white paper called for “a single, coherent security partnership between the UK and the EU”, covering both internal and external security co-operation. And in a presentation for EU negotiators in May 2018, the UK set out in some detail the arrangements that it hoped to negotiate with the EU, preserving as much as it could of its access and influence as a member-state.

At the time, the EU was unwilling to get into the details of the future relationship with the UK, whether in relation to trade and economic arrangements, or a foreign and security partnership. Even so, the relevant sections of the political declaration accompanying May’s withdrawal agreement pointed to a continued close relationship – described as a “broad, comprehensive and balanced security partnership”.

The Johnson government left this part of the political declaration almost untouched. But at some point Johnson will have to decide whether he, like May, wants a close security and foreign policy relationship with the EU, or something that enables him to claim that the UK has ‘taken back control’ of its internal and external security policy (even if it never lost it).

The current foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, came into office philosophically inclined to seek new allies outside the EU. Soon after his appointment, he wrote an article for The Sunday Telegraph in which he argued that while the UK wanted a strong relationship with European partners, “Brussels isn’t the only game in town”. Raab seemingly wants to avoid frequent formal meetings with the EU, and to work instead through ad hoc coalitions and small groups, and in NATO. Such bilateral and ‘minilateral’ approaches would enable the UK to influence some of its former partners, such as France and Germany, before they go off to formulate EU policy – but they would not fully replace a seat at the EU table.

Dominic Raab seemingly wants to avoid frequent formal meetings with the EU, and to work instead through ad hoc coalitions and small groups, and in NATO. Such arrangements would not fully replace a seat at the EU table.

After the debacle of the Suez crisis in 1956, when the US pressured the UK into withdrawing from Egypt, the UK has almost always aligned itself with the US on foreign policy issues, even when some of its European partners have not, most notoriously in the 2003 Iraq war. Recent events have shown the limitations and risks of such a policy, however.

US President Donald Trump has shown himself to be a particularly unreliable ally. He withdrew from the nuclear deal with Iran in the teeth of opposition from the UK as well as the rest of the EU; he announced that he was pulling US forces out of northern Syria without warning, still less consulting, the UK and others with troops in the area; and he authorised the assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani without giving his allies any chance to get their troops out of harm’s way in case of retaliation. The UK’s defence secretary, Ben Wallace, told The Sunday Times that the assumption made in the UK’s ‘Strategic Defence and Security Review’ in 2010 that the UK was “always going to be part of a US coalition is really just not where we are going to be”.

Meanwhile, China is increasingly assertive in Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere, and its foreign and security policy aims are rarely likely to correspond with those of the UK. Like most EU member-states, the UK has tended to let the EU speak out about China’s human rights record, while it has focussed on increasing British trade and investment relations with China. Now it will have to decide whether to stick with its principles or its economic needs. London may find that dealing with Beijing by itself is a lot harder than working as part of the EU.

Weakening foreign policy ties with the EU might make sense if the UK wanted to pursue a radically different international course after Brexit; but there is no sign of that – indeed, the UK has remained aligned with the EU over issues including Iran and sanctions against Russia. In the parliamentary debate on the new government’s programme in December 2019, the British priorities Raab listed – free trade, human rights, democracy and the international rule of law – are indistinguishable in substance from those set out by the EU in its 2016 ‘Global Strategy’, or espoused by leading member-states like France, Germany or Italy. At this point, it would make more sense for the British government to say explicitly that it expects to stay aligned with its EU partners on almost all international issues. That might at least create some good will – which may be in short supply in other parts of the negotiations on the future relationship.

Handled well, the negotiations on future law enforcement and judicial co-operation could also benefit both parties: the only winners from less effective information sharing or extradition arrangements will be criminals and terrorists, and the UK has much to contribute in terms of intelligence and policing capabilities.

The UK, however, has got off on the wrong foot with its negotiating partners after making unauthorised copies of the Schengen Information System database, to which – though not a member of the Schengen area – it has had access for border control purposes; and for failing over several years to pass on information to other EU member-states when their nationals were convicted of criminal offences in the UK. The Dutch liberal MEP Sophie in ’t Veld described the UK as “behaving like a bunch of cowboys”. The political declaration speaks of considering data exchange arrangements that “approximate those enabled by relevant Union mechanisms”. But the European Parliament, always sceptical of proposals to share EU citizens’ data with third countries, may well ensure that information sharing is much more limited. Co-operation with ‘Five Eyes’ intelligence partners or other non-EU countries will not compensate for what the UK loses.

Notwithstanding the bravado of Johnson & Raab, protecting the UK’s security & projecting its values in the world will be made harder by Brexit. The rest of the world could not fill the lacunae left by Brexit even if they wanted to.

Notwithstanding the bravado of Johnson and Raab, protecting the UK’s security and projecting its values in the world will only be made more difficult by Brexit. The rest of the world could not fill the lacunae left by Brexit even if they wanted to. The EU itself would certainly puzzle Palmerston, were he alive today. But he would have been just as bewildered by the approach of his successors, who risk unnecessarily alienating their European allies and simultaneously damaging the UK’s interests.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform.