No pain, no gain? The Digital Markets Act

- The Digital Markets Act (DMA) is a single set of rules for the largest digital platforms, intended to help improve competition in the EU. The rules will force big tech firms to change the way they operate, to promote more open markets.

- EU law-makers – the European Commission, member-states and Parliament – will finalise the DMA in the coming months. Negotiations will focus on the Parliament’s desire for the DMA to regulate fewer large platforms, but to impose more onerous restrictions on those which are regulated.

- Critics of the DMA argue that it will reduce innovation and make services worse for consumers.

- The DMA can enhance innovation – but only if law-makers keep its focus on each big tech firm’s core platforms (for example, Google’s search engine) where their dominance is most enduring. To promote innovation, EU member-states should be cautious about the Parliament’s desire for increased restrictions on big tech’s newer services.

- The DMA could make some online services worse for consumers in the short term. But a degree of short-term consumer inconvenience may be needed to promote greater competition. Greater competition will serve consumers better in the long run – for example, by giving them more choices and speeding up innovation.

- EU law-makers need to be pragmatic. If the DMA annoys users too much – or worse, causes new security vulnerabilities – it could lose credibility. The Commission therefore needs the power to exempt big tech firms from the rules in some cases. Without this type of safeguard, the DMA may become unpopular before it has the chance to succeed.

At the end of 2021, the European Parliament agreed on its preferred version of the Digital Markets Act (DMA), a set of rules intended to improve competition online. The DMA will shortly be followed by the Digital Services Act (DSA), which aims to make tech platforms responsible for tackling illegal and harmful content online. The DMA and DSA together form key parts of the EU’s plans to tame the power of big tech platforms in Europe.

The EU law-making institutions – the Commission, the Council of Ministers representing member-states, and the Parliament – will negotiate the final form of the DMA in the coming months. France took over the presidency of the Council of Ministers on January 1st 2022 and wants the DMA finalised rapidly, before the French presidential election in April. This is achievable: there are few areas of fundamental disagreement between law-makers. Broadly, compared with member-states and the Commission, Parliament wants the DMA to regulate fewer platforms; to set stricter rules on the platforms which are regulated; and to impose harsher penalties on platforms which do not follow the rules.

The DMA has many critics. Among them are several of the world’s largest tech companies – Amazon, Apple, Alphabet (which owns Google) and Meta (formerly Facebook) – whose core platforms, along with those of Microsoft, will be regulated by the DMA. These companies’ main concerns include that the DMA will reduce innovation in the long term and that it will worsen services in the short term.1 This policy brief explains the DMA’s approach to improving competition and then assesses these two concerns. It concludes that they have partial merit. However, these criticisms can still be addressed when the law-making institutions finalise the DMA. The EU institutions should keep the DMA targeted – the rules for those firms should focus on unlocking competitive bottlenecks, and allow some pragmatic exceptions. If they can manage this, then the benefits of the DMA should outweigh its shortcomings.

How the DMA will work, and what it will achieve

Digital platforms allow businesses to find and connect with vast numbers of consumers. In doing so, they have created new business opportunities for app developers, retailers, advertisers and others. They have increased competition in many markets, where previously only very large businesses could compete.

Competition authorities have observed that platform markets can become dominated by just one or two large players.

However, businesses are attracted to the platforms with the most consumers, and vice-versa. Competition authorities around the world have therefore observed that platform markets can become dominated by just one or two large players. These large players can then lock in consumers and businesses – who either have no viable alternative to the platform or face high costs of switching to a competitor.2 Platforms can then treat business users unfairly (because businesses must participate on the popular platform or lose their access to customers), lower the quality of their platform (for example, by reducing consumers’ privacy), or generally become less efficient.

To address this problem, the DMA will impose new rules on ‘gatekeepers’. ‘Gatekeepers’ are firms that meet two criteria. First, the firm must provide a ‘core platform service’. The DMA will define a list of these services, which will include search engines, operating systems and online marketplaces.3 Second, the firm must have a significant impact on the EU’s single market and have an entrenched and durable position. If a firm has a sufficiently high annual European turnover or market capitalisation, and its core platform service has a sufficiently large user base, the firm can be assumed to meet these second criteria. The three EU law-making institutions all want to set the criteria so that some European firms will be assumed to be gatekeepers – not just the well-known American platforms. The EU probably intends to dampen US concerns that the DMA unfairly targets American companies.4 In truth, the DMA is still focused on American big tech: most of the DMA’s rules are targeted at the services of the largest global platforms, which happen to be US-based, and most regulatory attention will be focused on them too.

The rules will apply to each gatekeeper’s largest platform services. The DMA would regulate Facebook’s social network; Google’s search engine; operating systems like Microsoft Windows, Apple iOS and Google Android; and online marketplaces like Amazon. Other regulated platform services could include video-sharing sites like Google’s YouTube; instant messaging services like Facebook’s WhatsApp; Google’s and Facebook’s digital advertising services; and other online services that connect businesses and consumers, like online travel and accommodation booking sites and food delivery platforms.

The DMA privileges efficiency over precision. All gatekeepers who operate the same type of platform need to comply with the same set of rules. This differs from the EU’s economic regulation of dominant players in other sectors, such as telecoms, where regulators design rules tailored to each regulated firm and continually update those rules to reflect market changes. In areas such as telecoms, regulation is often rolled back as competition improves.

The DMA’s rules partly aim to force platforms to treat their business users and consumers more fairly.5 But most of the rules aim to inject more competitive pressure into digital markets. These have three objectives:

- Increasing competition for core platforms – like Google’s online search engine, Amazon’s marketplace, or Facebook’s social media network. To do so, the rules do two things. First, they tackle platforms’ ability to lock in their customers and business users. For example, these platforms could no longer prevent businesses from contacting their customers directly and have future transactions take place outside of the platform. Second, the rules make it easier for competing platforms to be commercially viable without needing the vast amounts of data that some of the largest platforms enjoy today. A smaller competitor to Google’s search engine would, for example, be allowed access to Google’s own datasets.

- Creating a level playing field within gatekeepers’ marketplaces. Some gatekeepers run marketplaces or app stores where they sell their own products but also allow other businesses to compete with them. The DMA tries to ensure gatekeepers cannot use their platforms to unfairly advantage their own products.

- Increasing competition for a gatekeeper’s ‘ancillary services’ – those services that are not part of the core platform, but are often sold with it. For example, merchants can list their goods on Amazon’s marketplace, and they can pay for Amazon to deliver their items, or use a third-party delivery service. The DMA limits how a gatekeeper can use their core platform to promote or improve their ancillary services. A search engine like Google could list its own ancillary service as the first search result if it is not the best answer to the user’s search query. In this way, big tech firms would have fewer advantages over smaller businesses which do not have their own large platform.

Big tech firms would have fewer advantages over smaller businesses which do not have their own large platform.

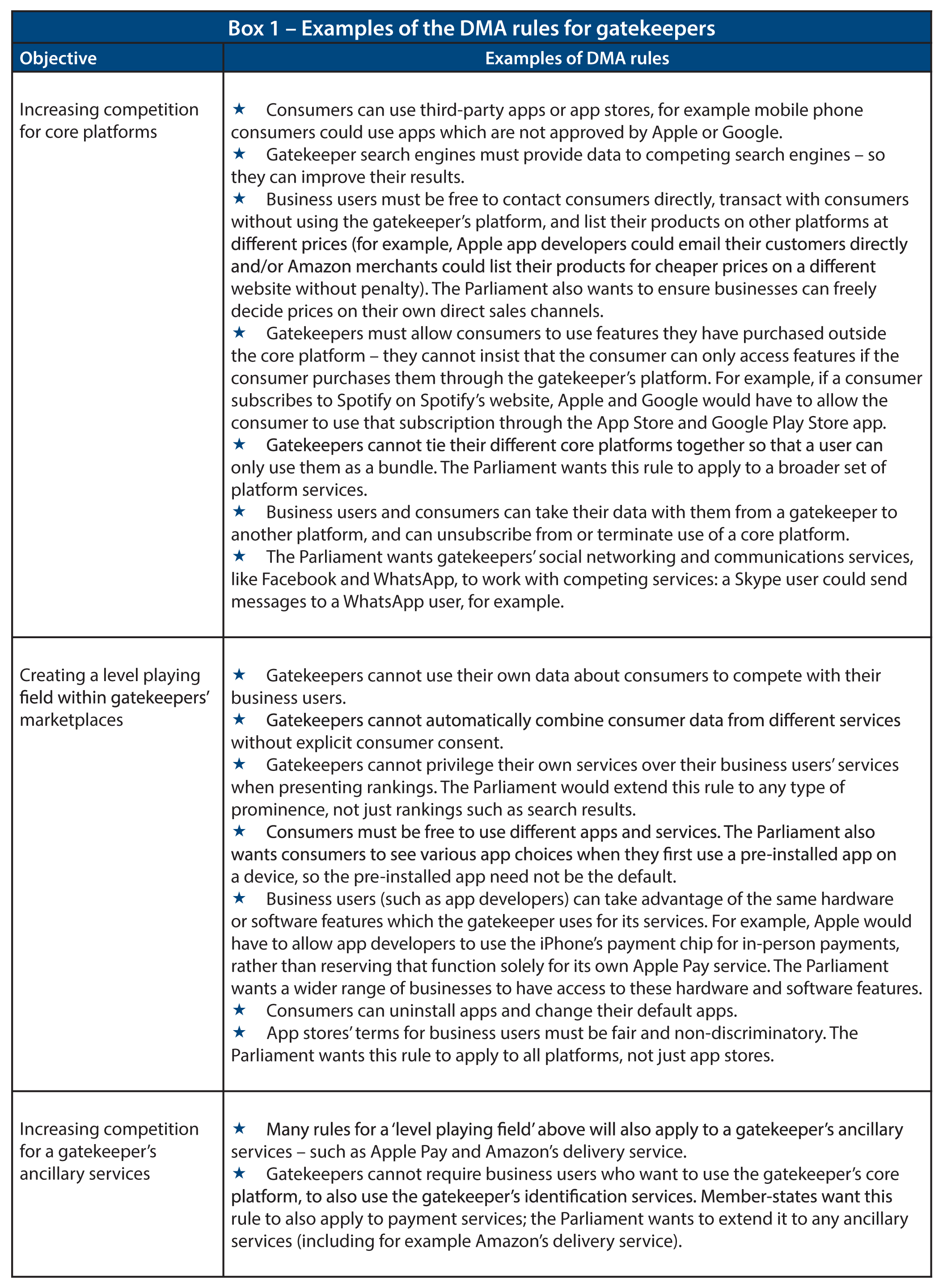

Box 1 sets out the three types of rules in more detail, and explains where the Parliament wants more rules than the Commission or EU member-states. A few rules simply codify existing business practices. In those cases, the DMA would still help smaller businesses, by giving them more certainty that the gatekeeper will not change that business practice in future.

The DMA’s impacts on competition are likely to be mixed. In most cases, strong direct competitors to the largest platforms probably will not emerge. Consumers now use Google search, Amazon’s marketplace or the Apple app store on their iPhone by ingrained habit. Even a well-resourced competitor would struggle to change these habits – Microsoft’s Bing search engine has had little traction. And in some cases, a platform is the most valuable to consumers or businesses simply because it is the biggest and can therefore provide the best service – so a smaller competitor is unlikely to succeed.

But the DMA could still increase competitive pressure on platforms in other ways. Take mobile app stores – the DMA would allow users to download apps directly from the internet rather than needing to use Apple’s and Google’s app stores (or a competing app store). If just a few consumers start buying apps more cheaply that way, then Apple and Google may lower the commission they charge app developers on their app stores to keep consumers on their platforms. Similarly, the DMA will close off some methods gatekeepers may use to hinder potential competitors, and will therefore force gatekeepers to focus harder on innovating and improving their platforms to stay ahead. In this way, the DMA can have positive outcomes even if gatekeepers do not lose much market share.

The DMA may also increase competition within gatekeepers’ marketplaces. But the results here may be more mixed, because the DMA tends to assume some gatekeeper practices are anti-competitive, even though this is not always clear. As an illustration, alternative delivery services dislike that Amazon gives special advantages to retailers who use Amazon’s own delivery service. But if this allows Amazon to give consumers a better service, then it should not be objectionable – so long as Amazon does not drive all competing delivery services out of the market. In some EU member-states, Amazon’s market share is not especially large,6 so competing delivery services can partner with other online retail marketplaces. The same might not be true in other EU member-states where Amazon’s market share is much larger.7 However, the DMA is not nuanced enough to distinguish between these two cases. The DMA may therefore improve competition within marketplaces in some cases, but also dampen competition unnecessarily in others.

Similarly, the DMA might improve competition for gatekeepers’ ancillary services, by tackling cases where gatekeepers effectively lock consumers and businesses into the gatekeeper’s additional services, thereby excluding competitors. For instance, when consumers make payments within mobile apps, they currently must use Apple’s and Google’s payment services. The DMA will give consumers more choices. But for other ancillary services, there is already a degree of competition and innovation. For example, all of the big tech firms are developing new features and devices – like mapping and translation tools. Many of these new services already work on multiple platforms, so they do not contribute to consumer ‘lock in’. There is not much need for the DMA to intervene and ‘fix’ competition for these services.

Will the DMA kill innovation in the long term?

In many markets, the immediate objective of competition policy is to reduce prices. This is also true in some digital markets. Competition might reduce Amazon’s marketplace fees, or the commission Google and Apple charge on app store sales, and it could make digital advertising cheaper for businesses. Consumers also pay a price for using ‘free’ digital services, by allowing their personal data to be collected and used for targeted advertising. Greater competition could lead to more privacy-conscious services emerging (making those services ‘cheaper’), or to services improving (so consumers get better value).

The most significant potential benefit of competition in the long term, however, is not price reductions, but increased innovation – which gives consumers and businesses new features and new services. If the DMA ends up harming innovation, that would eventually overshadow any short-term benefits from lowering prices.

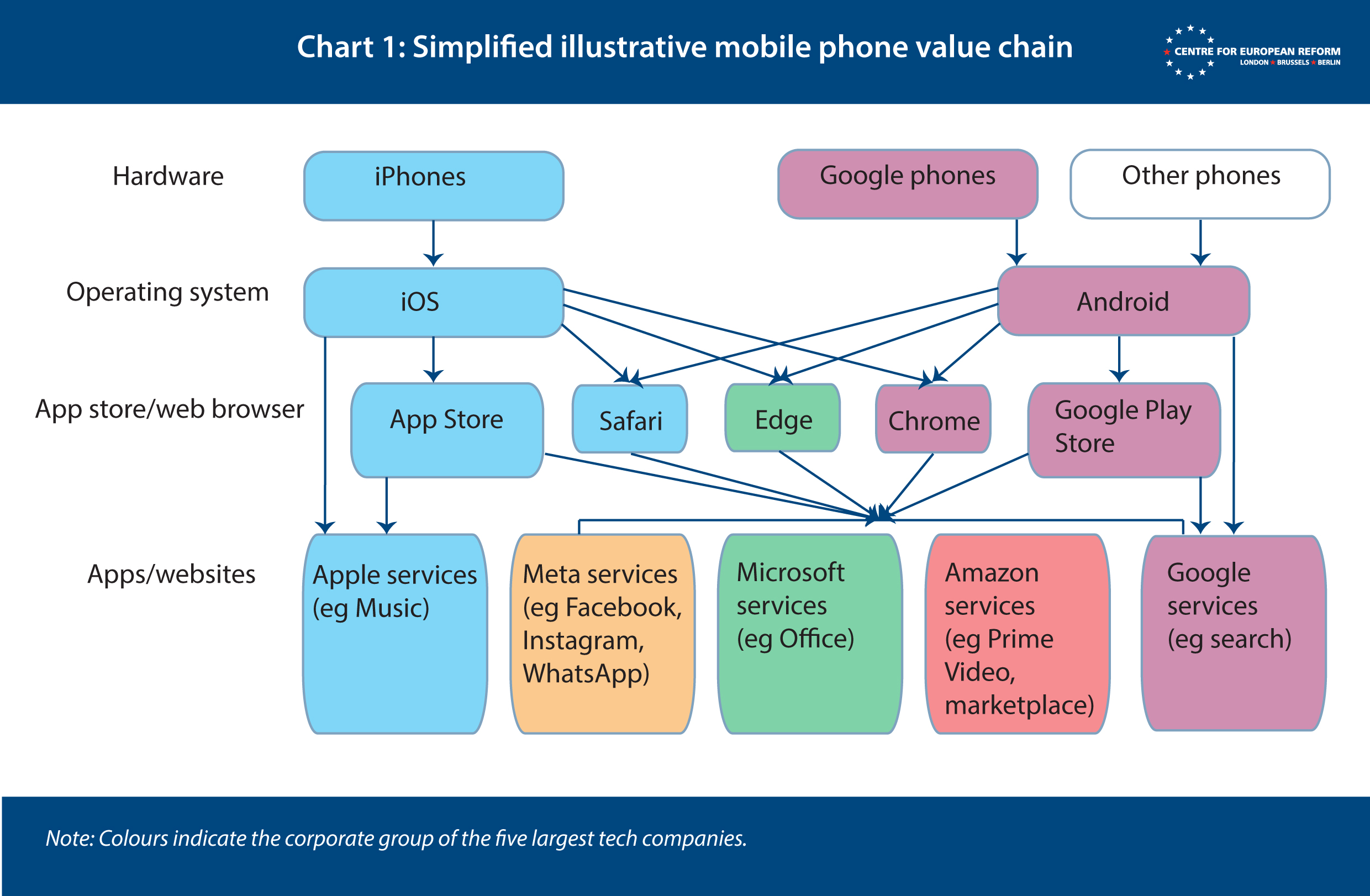

Big tech firms are concerned that the DMA might harm innovation. In their account, they are not stereotypical lazy monopolists – they spend large amounts on R&D. Chart 1 explains one reason why they spend so much on innovation: many of the largest big tech firms rely on other big tech firms’ hardware, operating systems, app stores and browsers to reach consumers. This interdependency of big tech firms poses strategic risks for each of them individually – a gatekeeper could at any time start disadvantaging another big tech firm. Vulnerability to other platforms’ commercial decisions gives many big tech firms incentives to innovate in order to avoid this dependency.

For example, Facebook and Google recently experienced the risks of dependency. Many consumers access Facebook and Google through Apple’s devices. Apple recently imposed new rules on its app developers, requiring them to ask consumers whether they wanted to be tracked across the internet.8 Most consumers did not consent. As a result, Facebook and Google’s advertising revenues dropped.

Gatekeepers are innovating to remove these dependencies and avoid new ones. Google created its own operating system, Android, to better steer users to its own apps; Facebook is investing in virtual 3D spaces, so consumers will use its own Oculus and Portal hardware to access its services rather than computers and mobile phones; and all big tech firms are exploring new ways to reach consumers, such as through voice assistants, automated cars, and smart devices. If big tech’s account is true, the DMA could reduce the pace of innovation for two reasons:

- If each gatekeeper platform must be more neutral and predictable, as the DMA will require, then each gatekeeper will be more relaxed about its own dependencies on other gatekeepers. There will be fewer reasons to innovate to avoid them.

- If gatekeepers face limits on how they use their existing services to promote or improve their newer services, then these newer services could be lower quality and less likely to succeed.

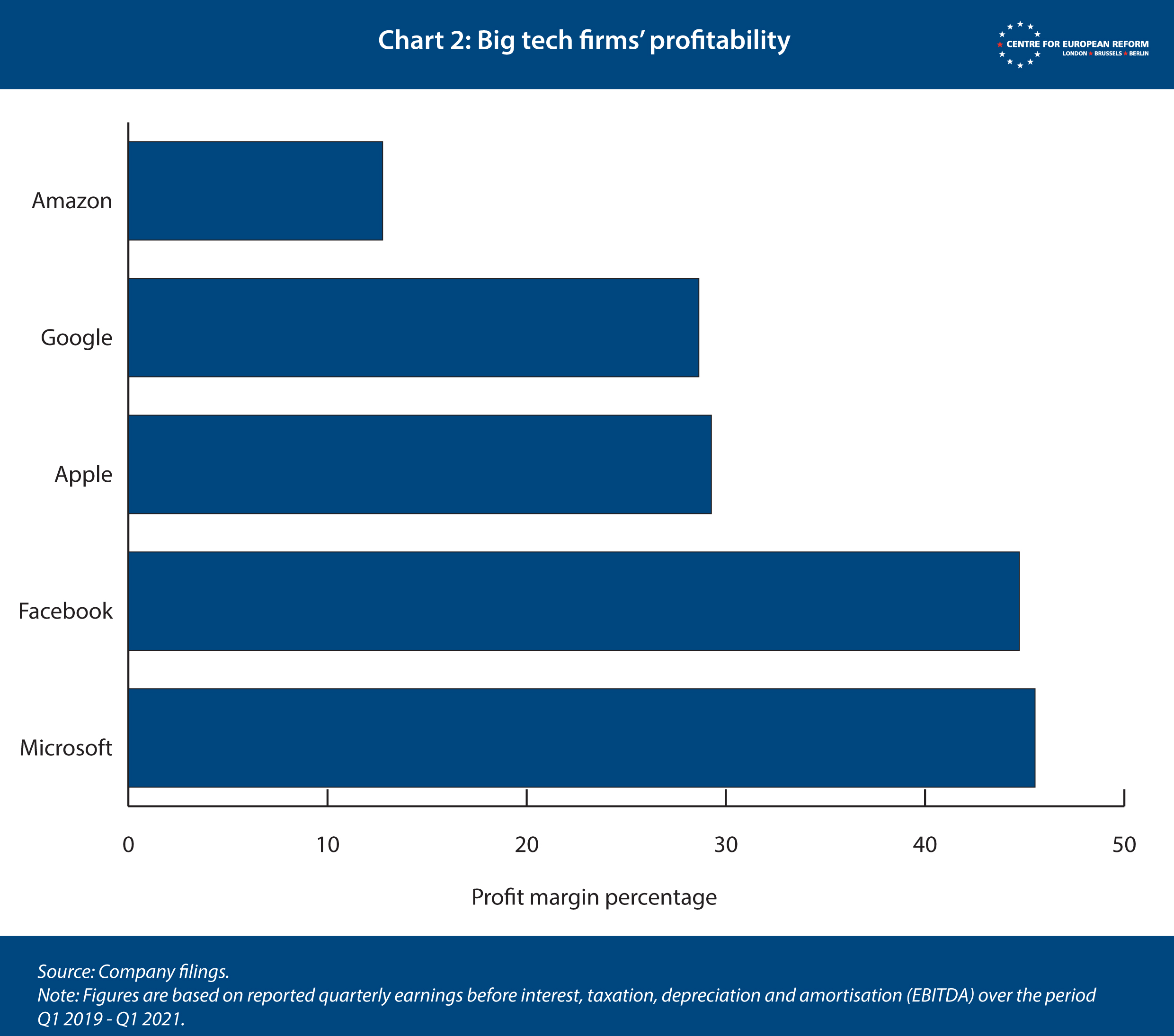

But the relationship between tech firms is rather less antagonistic than big tech suggests. For one thing, many big tech firms’ core platforms are so entrenched that their reliance on other gatekeepers is merely inconvenient, not life-threatening. For example, when consumers started spending more money on mobile devices, Microsoft famously failed to successfully adapt – and the mobile sector is now dominated by Apple and Google. But, as Chart 2 shows, Microsoft did not suffer the same fate as Yahoo, AltaVista and similar tech firms which failed to adapt in the 1990s, and have since faded into oblivion. Instead, Microsoft has the highest profit margins of any of the largest platform companies. Even if consumers now spend more time on their mobiles, they still have personal computers and need pricey Windows and Office software.

Similarly, although Facebook and Google no doubt disliked Apple’s recent privacy changes, which prevented them from tracking consumers who did not consent, the impact on their advertising revenue was hardly catastrophic. A privacy-focused business like Apple is unlikely to try to replace data-heavy businesses like Google’s search or Facebook’s social networks. So big tech firms are probably already quite relaxed about many of their dependencies.

Gatekeepers rarely compete against each other in their core markets. And when they do, they seldom succeed.

This relaxed attitude points to a broader problem: gatekeepers rarely compete against each other in their core markets. And when they do, they seldom succeed – think of the Microsoft Bing search engine, the Google+ or Apple iTunes Ping social networks, or Amazon’s Fire Phone, none of which achieved much success. Instead, there is evidence of co-operation. For example, Google pays Apple up to $15 billion each year to make Google search the default on iPhones.9 This practice deprives other search engines of perhaps the only way to rapidly get a critical mass of mobile users. According to The New York Times, Facebook also agreed not to support a challenger to Google’s advertising business.10 The larger gatekeepers’ core platforms grow, the greater their desire to compete only at the margins of each other’s businesses and to focus on their own ecosystems instead. This incremental innovation benefits consumers – but not as much as radical, disruptive innovation which seriously threatens gatekeepers’ core platforms.

The DMA is therefore justified in regulating the core platforms of gatekeepers, where there is often little competitive pressure, to help nascent or potential competitors. Innovation will increase if the DMA puts more competitive pressure on gatekeepers’ core platforms, forcing big tech to work harder to improve or evolve their core services. Big tech might also have stronger incentives to develop newer services if their core platforms stopped being entrenched ‘cash cows’.

Innovation is more at risk, however, when the DMA tackles big tech’s ancillary services. Ancillary services do need some regulation. In certain cases, big tech firms entirely exclude competitors. But at the same time, big tech firms are investing heavily in other ancillary services, often in competition with each other – and the DMA could impose constraints on how they do this. Take the DMA rule which prevents a gatekeeper from using its core platform to promote an ancillary service, or limits the use of data from the core platform to improve an ancillary service. The ancillary service might never be rolled out at all – for example, if it required a huge critical mass of consumers to succeed, and a gatekeeper could only achieve this by using its core platform to encourage consumers to try it out. The Parliament’s suggestion to extend more of the DMA rules to ancillary services is therefore dangerous. Where the DMA rules cover more than gatekeepers’ core platforms, those rules should be limited to where gatekeepers exclude competitors entirely, or seriously restrict consumers’ freedom of choice – they should not stop a gatekeeper from giving its own ancillary service an advantage.

Fortunately, the EU does not need to rely solely on the DMA to stop big tech firms from giving advantages to their ancillary services. The European Court of Justice recently accepted in the Google Shopping case that when a gatekeeper advantages its ancillary services unfairly, this can violate EU competition law. This ruling only directly applies to results on Google’s search engine (which the court considered “superdominant”). In addition, the Italian competition authority recently found that Amazon contravened competition law, when it gave preferential treatment to merchants who used Amazon’s delivery service. These cases show that competition law is already capable of considering, on a case-by-case basis, whether gatekeepers are acting anticompetitively when they use their platforms to promote or improve their other services. If regulation is used to achieve the same result, that regulation should be nuanced and flexible – like Germany’s digital markets regime or the proposed UK regime, both of which would allow the competition regulator to set individual rules for specific firms. It should not rely on an inflexible instrument like the DMA.

Therefore, to protect innovation when finalising the DMA:

- The Commission, EU member-states and the Parliament should adopt the proposed rules to improve competition on gatekeeper’s core platforms. Some of Parliament’s proposals to strengthen these rules are generally helpful – in particular, its proposal to force gatekeeper social media platforms like Facebook to work with competitors (known as ‘interoperability’). These rules would allow consumers to move to competitors and still see their friends’ information, even if their friends remained on Facebook. This means Facebook would have to compete with alternatives based on its quality – not just its incumbency. While interoperability rules will take time, they will put the most competitive pressure on big tech firms’ core businesses over the long run.

- The Commission and the EU member-states should be more cautious about the Parliament’s proposed new rules for these services. These rules are already excessive, as they prevent gatekeepers from using their core platforms to develop, promote and improve their ancillary services, even though this can often improve competition. But the Parliament’s suggestions go even further. To illustrate, when a consumer first uses a gatekeeper device, the Parliament wants the gatekeeper to proactively offer a consumer a range of app choices. This would inevitably harm innovation. To take one case, Google would never have developed its free Android operating system if it was prohibited from using Android to encourage consumers to use Google’s other services. The Commission and member-states should ban gatekeeper practices that exclude competitors entirely, or seriously restrict consumers’ freedom of choice. For other cases, the EU should rely on competition law.

Will the DMA harm consumers in the short term?

The second argument made by critics of the DMA is that it will almost immediately make big tech’s services worse. Here are some possible examples:

- A gatekeeper could no longer combine consumers’ data from across the firm’s different services into a single profile without consent. Gatekeeper services could therefore become less well integrated and personalised, and at worst consumers could be plagued by even more ‘cookie banner’-style requests for consent.

- Business users would be allowed to reject Apple and Google’s identification or payment services, and force consumers to use the business’s preferred alternative. This could require fiddly logins to access business users’ preferred payment providers, compared to the simplicity of Apple Pay and Google Pay.

- Apple and Google would have to allow users to install unapproved apps and app stores, which could lead to consumers being more easily misled into installing unsecure software.

The DMA will have to make services ‘worse’ to generate more competition, so that consumers are prompted to explore their choices.

These consequences are a feature of the DMA – not a bug. Big tech platforms make their own services work together seamlessly and securely, precisely because many consumers do not bother, or do not want the risk of, leaving the platform’s ecosystem. The DMA will have to make services ‘worse’ to generate more competition, so that consumers are prompted to explore their choices. As one illustration, it is often easiest for consumers to pay within apps using Apple Pay and Google Pay. But Apple Pay and Google Pay have high fees, which app developers indirectly pass on to consumers. Businesses should be able to give consumers the choice to use cheaper but more fiddly payment options, even if this makes the process less streamlined. By putting more friction in the consumer experience, the DMA is therefore a significant step away from EU competition law – which generally tries to avoid short-term consumer harm.

The Parliament, the Commission and member-states should acknowledge the trade-off between short-term consumer convenience and the longer-term benefits of making digital markets more competitive. They should also recognise that these problems should resolve themselves over time. For instance, big tech firms could adapt their services so they do not require as much personal data. New payment methods will probably become more seamless, if they are more widely adopted. And secure and trustworthy third-party app stores, or means of proving an app is safe, will probably emerge to compete with Apple and Google – probably from other large tech firms like Microsoft.

Rather than eliminating inconvenience entirely, law-makers should therefore focus on ensuring any inconvenience is not so sudden and severe that consumers hate the DMA. If the DMA annoys users too much or – worse – causes new security vulnerabilities, it could lose credibility before it even has the chance to make a difference. Gatekeepers may themselves act in ways that favour such an outcome, in the hope of persuading law-makers to roll back the DMA. Law-makers will remember, for example, that Google withdrew its Google News services in some countries, after laws were introduced requiring it to pay news outlets for content.

Numerous experts, including the EU’s own, have therefore called for the Commission to allow particular gatekeepers exemptions from specific DMA rules if this is necessary to avoid unjustifiable negative effects for consumers.11 This is a sensible safeguard, given the DMA’s crude approach to setting a single set of rules for all platforms of the same type.

Currently, the Parliament and the EU member-states have agreed on one exception: a gatekeeper can introduce its own measures to protect cyber security, before allowing unapproved apps to run on its devices or use the device’s full functionality. Cyber security undoubtedly justifies an exception: the DMA’s reputation would be enormously damaged if it significantly increased the risks of data breaches.

However, the Parliament and the EU member-states have not fully understood that this is a broader problem with the DMA, and the exception they have proposed is too narrow:

- Threats to cyber security are just one example of a possible negative consequence from the DMA. Exceptions should be broad enough to allow the Commission to avoid other negative consumer consequences, too, as long as the inconvenience is serious enough and the exception does not undermine competition in the long run.

- Exceptions should apply to all the rules, not just those for apps and app stores. For example, the DMA constrains gatekeepers from combining datasets from different services. But there may be good security reasons to do so, which are unrelated to competition – such as to detect fraud more effectively.

The Parliament and the EU member-states have also designed the exception to be a ‘quick fix’, by allowing each gatekeeper to invoke the exception itself. This would allow gatekeepers to design security measures with one eye on hindering competitors, rather than applying exceptions in a way which preserves the DMA’s intent as far as possible. The Commission instead needs to work with gatekeepers on a case-by-case basis, individually approving how each big tech firm will rely on any exemption and which measures it will adopt, to ensure exceptions are not abused.

The Parliament and the EU member-states do not want the Commission to have this level of flexibility or close engagement with gatekeepers. Instead, they want the DMA to be as ‘self-executing’ as possible, so that once a firm is a gatekeeper, the rules will automatically apply and the Commission will rarely need to make any further judgements. This approach is intended to avoid Commission decisions being endlessly appealed, and reflects a fear that the Commission will be inundated with requests and technical detail. The desire to ‘set and forget’ a single set of rules is understandable. However, setting a single set of rules for a diverse set of companies inevitably risks creating serious unintended consequences. Regulators constantly update regulation in other regulated markets, like telecoms, to reflect changing market circumstances. It takes time and significant resources to do so properly. The EU will find the risks even greater in the dynamic and complex tech sector if the Commission cannot properly engage with gatekeepers and design targeted exemptions to avoid negative effects on consumers.

Conclusion

The DMA will inevitably be a crude instrument – but it can still achieve more good than harm. For this, the EU institutions will need to tweak some of its proposals.

The French presidency of the EU began on January 1st. French President Emmanuel Macron wants to finalise the DMA before the French presidential election in April, to prove to voters he is tough on big tech. The EU institutions will be under significant pressure in trialogue negotiations to finalise the DMA quickly. But the EU will be living with the DMA for years to come, and it is not just American big tech firms who will have to comply – the three EU institutions agree that some European platforms should be regulated too. Law-makers therefore need to ensure the DMA promotes innovation and does not cause too much short-term harm.

To protect innovation, the DMA should continue to focus on regulating the core services where gatekeepers have been dominant for many years. The Commission and member-states should therefore take up MEPs’ proposal to mandate that social media services work with competitors. But to protect innovation, EU member-states should be more cautious about the Parliament’s plans to put more restrictions on big tech’s newer and more innovative services – limiting those rules to where competitors are excluded from the market, or consumers’ freedom of choice is severely restricted.

Some consumer inconvenience is unavoidable if more competition is to be achieved in the long run, but the EU needs to balance short-term pain against long-term gain. A broader and better designed exception would help protect consumers – including ensuring they are not subjected to major cyber security risks, without giving gatekeepers an opportunity to undermine the DMA. Without such a broader exception, Europeans may end up hating the DMA as much as they hate endless cookie requests. If consumers are not on its side, the DMA may be dead on arrival.

2: Zach Meyers, ‘Taming ‘Big Tech’: How the Digital Markets Act should identify gatekeepers’, CER insight, May 4th 2021.

3: Law-makers largely agree on this list, but the European Parliament also wants to include web browsers, virtual assistants and connected TVs as platform services.

4: In December 2021, US commerce secretary Gina Raimondo said she had “serious concerns” the DMA would “disproportionately impact” American firms.

5: One example is Parliament’s proposal to prohibit targeted advertising for minors and for adults who do not repeatedly consent to it. While regulators have concerns about competition in digital advertising markets, this proposal does not appear to address those problems – instead it is focused on consumer protection.

6: Mimi Billing and Kit Gillet, ‘Amazon is a minor ecommerce player across much of Europe – here’s why’, Sifted, December 9th 2020.

7: The Italian competition authority has alleged this is true in Italy. See Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato, ‘Sanzione di oltre 1 miliardo e 128 milioni di euro ad Amazon per abuso di posizione dominante’, December 9th 2021.

8: UK Competition and Markets Authority, ‘Mobile ecosystems market study interim report’, December 14th 2021.

9: Daisuke Wakabayashi and Jack Nicas, ‘Apple, Google and a deal that controls the internet’, The New York Times, October 25th 2020.

10: Daisuke Wakabayashi and Tiffany Hsu, ‘Behind a secret deal between Google and Facebook’, The New York Times, January 17th 2021.

11: German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, ‘A new competition framework for the digital economy’, September 2019; Heike Schweitzer, ‘The art to make gatekeeper positions contestable and the challenge to know what is fair: A discussion of the digital markets act proposal’, SSRN, May 2021; Jacques Crémer, Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye and Heike Schweitzer, ‘Competition policy for the digital era’, European Commission, 2019.

Zach Meyers is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

January 2022

A number of technology companies including Amazon, Apple and Facebook are corporate members of the CER. The views expressed here, however, are solely the author’s, and should not be taken to represent the views of those companies.

View press release

Download full publication

Comments