Europe's clean tech industry between Trump's policies and Chinese pressure

- The second Trump administration has made a U-turn on industrial policy designed to support decarbonisation, while making a protectionist trade policy its hallmark. US tariffs make the global trade environment extremely volatile, while the rollback of generous US subsidies creates both challenges and opportunities for European clean tech producers:

- First, US demand for many clean technologies has started to fall, and is set to contract further as some consumer subsidies for clean tech are phased out sooner than expected and others entirely stopped.

- Second, the future US supply of clean technologies will be lower than expected, but because not all manufacturing subsidies for clean tech are cut simultaneously, the drop in demand may be larger than that in supply.

- Third, the new tariffs might squeeze remaining Chinese clean tech exports out of the US market, possibly providing some opportunities for EU exporters to capture China’s market share.

- If US demand falls by less than domestic supply and Chinese imports combined, EU exporters could benefit from this opportunity. Otherwise, exports to the US will likely fall.

- In the short term, the prospects for exports of EVs and wind energy equipment will be particularly damaged, since they benefited from provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the post-pandemic stimulus package launched by former US President Joe Biden to support climate and clean tech investments. US domestic capacity for battery manufacturing is growing, so it will be difficult for EU battery producers to seize a large market share. Some smaller industries could benefit from Chinese goods such as heat pumps and electrolysers being largely excluded from the US market.

- At the same time, China’s oversupply of many clean tech products – from electric vehicles to solar panels – has increased. This puts EU-based manufacturers under pressure from low-cost, often subsidised competition, and risks deepening Europe’s dependency on Chinese tech. Due to US trade barriers, cheap Chinese exports are being redirected towards Europe, amplifying these pressures.

- In sum, European clean tech producers are being hit by two policy shocks, originating in the US and China: they suffer from weaker sales abroad and tougher competition at home.

- But the EU still has global leaders in clean tech manufacturing, in areas such as wind equipment, heat pumps, next-generation batteries and electrolysers. By building on its industrial and technological base, and leveraging its large internal market, the EU can claim a leading position – but it needs to deploy a coherent clean tech strategy quickly.

- A policy response is needed urgently to prevent these temporary shocks from destroying the EU clean tech industry, and from leading to long-lasting import dependency on a few suppliers of clean tech. Having recognised too late the danger of import dependency on natural gas from Russia, Europe should learn from its past mistakes.

- An effective EU policy strategy for clean tech should encompass trade defences against Chinese overcapacity, EU-level production support to complement national state aid for clean tech, and regulatory stability to boost domestic demand for clean tech. The EU should:

- Step up trade defences against Chinese overcapacity in strategically selected clean technologies, including through targeted tariffs, European preferences in public procurement and screening foreign direct investments.

- Support clean tech demand in the EU to offset the US demand shock, by sticking to a clear and predictable regulatory framework, and by providing purchase incentives where needed.

- Boost EU-level support to enable strategic emerging industries to grow, complementing national state aid with EU instruments such as Important Projects of Common European Interest, the planned European Competitiveness Fund and Horizon Europe.

1. Introduction

When presenting the Green Deal Industrial Plan in 2023, Ursula von der Leyen stated that “the race is on to determine who is going to be dominant in the clean tech market in the future”. In 2025, this race has shifted substantially: Europe’s clean tech producers are now hit by two powerful shocks. US tariff policy under Trump 2.0 is creating massive uncertainty for trade, while the rollback of clean industrial policy puts clean tech investments in the US on hold, dampening US demand for European clean tech exports. At the same time, China’s structural oversupply, combined with low manufacturing costs for many clean tech products – from electric vehicles to solar panels – has intensified. Additionally, US trade barriers have led to the redirection of cheap Chinese exports towards Europe, amplifying price pressure on EU-based manufacturers and deepening Europe’s dependency on Chinese tech. The immediate effect is a squeeze on European producers from weaker sales abroad and tougher competition at home.

The window for the EU to respond is narrow. Without timely action to shore up its industrial base, the current squeeze could harden into lasting dependency on a few foreign suppliers of critical clean technologies. Letting Europe’s clean tech base erode through inaction would be a serious strategic mistake, given that the global importance of these industries will only grow in coming years. Despite current challenges, the EU, with its strong industrial and technological base, has all the potential to be a leader in the clean tech race. The EU still has global leaders in wind equipment, heat pumps, next-generation batteries and electrolysers, as well as a large internal market that can create economies of scale. By building on these strengths the EU can claim a leading position – but only if it moves fast and decisively.

The EU therefore needs a short-term, sector-specific response to enable it to weather the immediate shock – protecting European clean tech industries from the impact of US tariffs and redirected Chinese exports – while laying the groundwork for longer-term competitiveness once global demand rebounds. An effective EU policy strategy for clean tech should encompass trade defences against Chinese overcapacity, EU-level production support to complement national state aid for clean tech, and regulatory stability to boost domestic demand for clean tech.

In this paper, we discuss how recent shifts in US trade and industrial policy are changing the prospects for Europe’s clean tech industry, focusing on equipment for wind and solar energy generation, batteries, EVs, electrolysers and heat pumps. We conclude with detailed policy recommendations to strengthen these key industries.

2. Tariffs up, industrial policy down: How US actions affect EU clean tech producers

This section examines how recent US policies are reshaping Europe’s clean tech industry in two distinct ways. Section 2.1 looks at the impact of trade turmoil on the EU market – how renewed US tariffs and Chinese overcapacity are redirecting low-priced Chinese exports toward Europe, intensifying price competition and import dependency. Section 2.2 then turns to the impact on EU exporters, analysing how the rollback of US climate support and weaker domestic demand under Trump affect European producers selling into the American market.

2.1 Trade diversion: ith new US trade policy, the EU market is facing greater inflows of cheap Chinese clean tech

For years, China has been providing ample industrial policy support to its clean tech sectors, including massive subsidies. The result is a persistent supply glut: despite record-high clean tech deployment at home, large parts of Chinese capacity remain underutilised. Facing a saturated home market, Chinese firms are increasingly exporting excess output. Thanks to their willingness to reduce export prices and accept the resultant losses,1 China’s market share in the global market for clean tech has been increasing quickly.

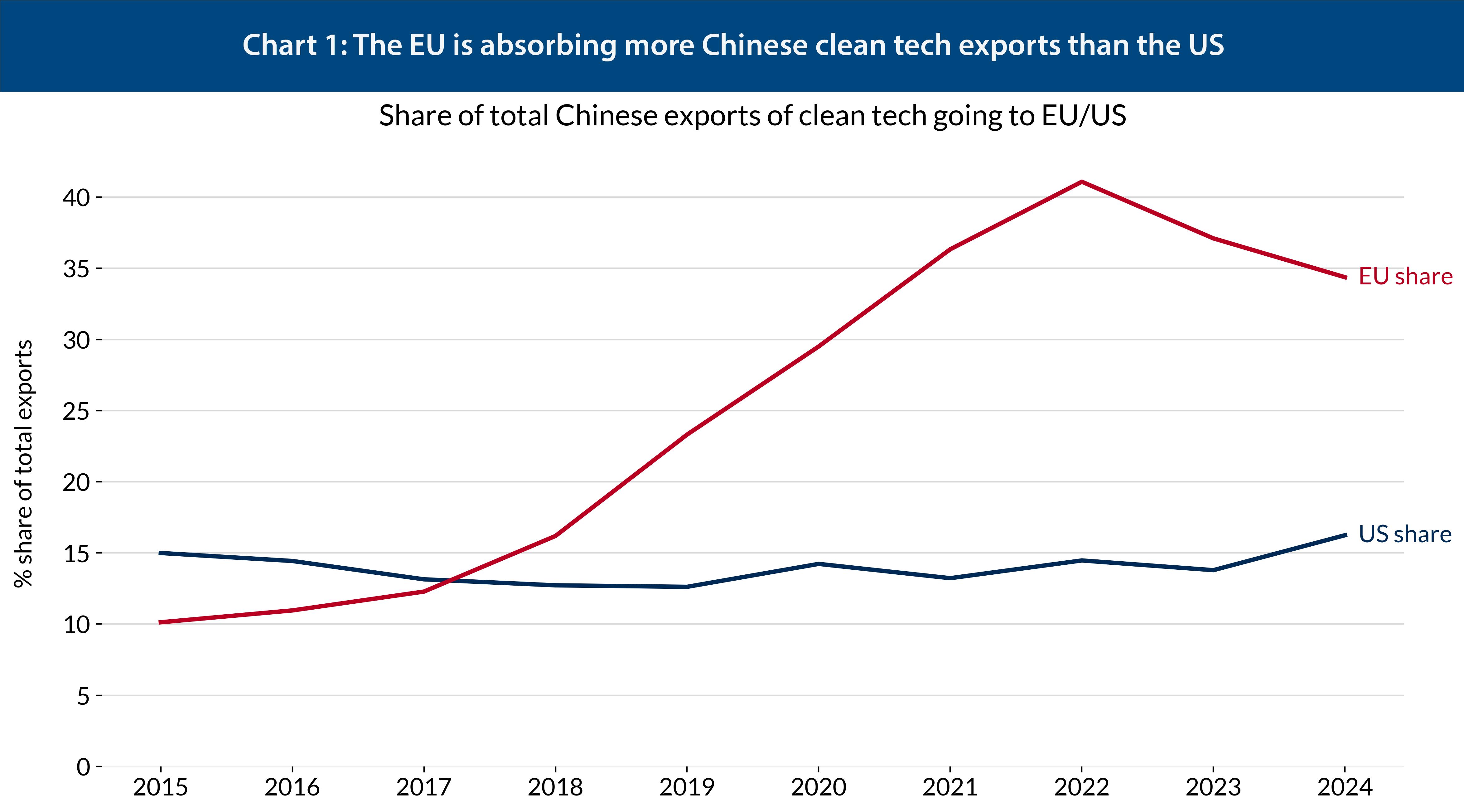

Past US tariff hikes increased the inflow of Chinese clean tech to the EU market. Under the first Trump administration, the US created widespread trade barriers to China. The Biden administration broadly maintained this protectionist strategy: the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the post-pandemic stimulus package supporting climate and clean tech investments, largely excluded foreign producers, including EU ones. Moreover, the Biden administration kept high tariffs, especially on China. As a consequence, Chinese exports have been redirected away from the US and towards more open markets such as the EU. As shown in Chart 1, in 2023, around 40 per cent of China’s clean tech ex-ports across six major technologies went to Europe, up from 12 per cent in 2016. At the same time, the share of Chinese clean tech exports to the US stagnated. This indicates that the EU has absorbed some of the Chinese export volume displaced from the US market.

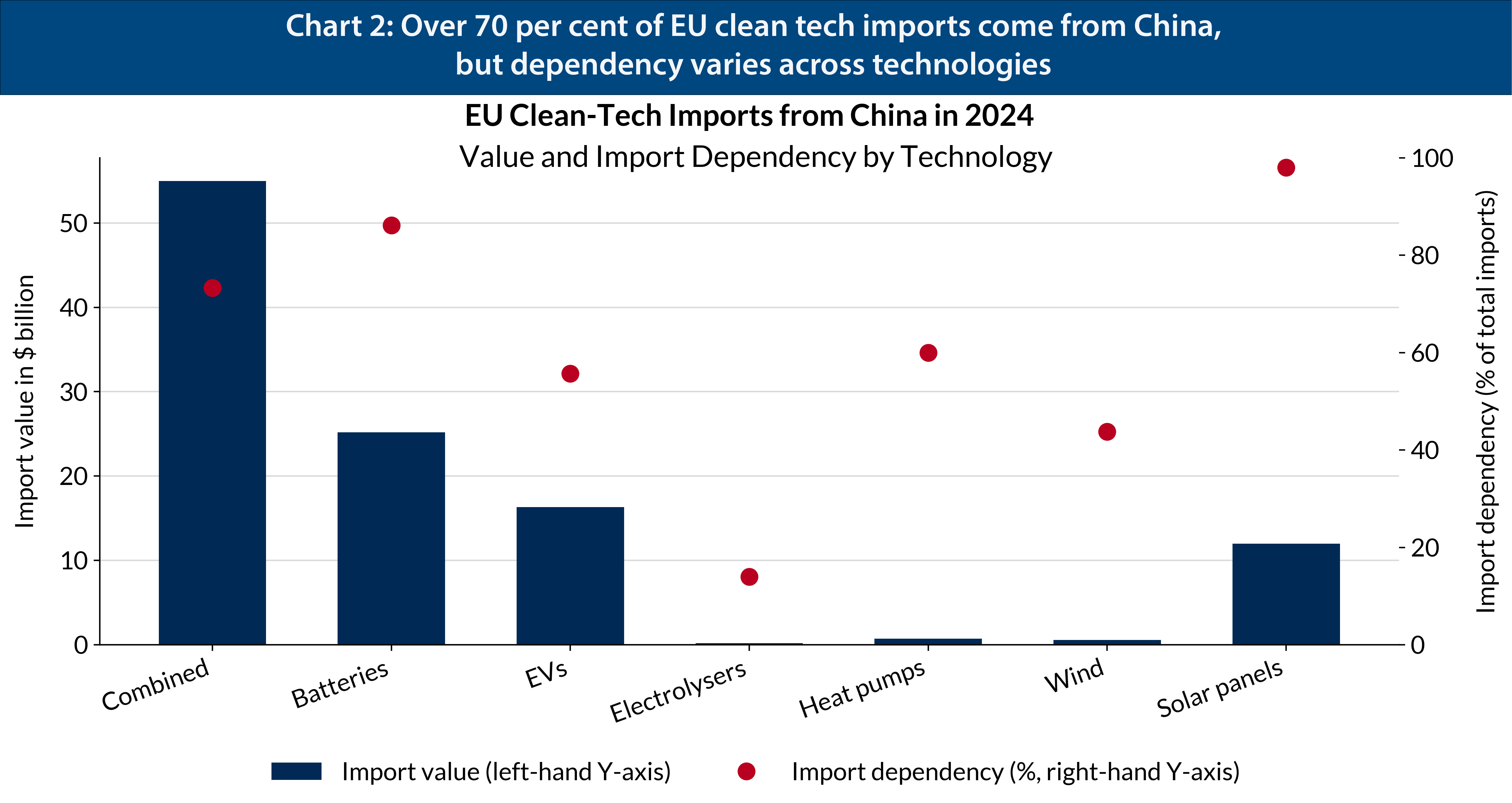

By 2024, about 73 per cent of the EU’s clean tech imports originated in China (Chart 2). This growing import concentration makes Europe highly vulnerable to tariff-induced price competition from Chinese firms, as new US trade barriers instituted by President Trump in 2025 continue to redirect low-priced Chinese exports into the EU market.

At the same time, it is important to distinguish between the share of EU imports coming from China for a given good and China’s market share in the EU: these metrics indicate different levels of dependency. For example, Chinese EVs make up about 60 per cent of EU imports, as illustrated in Chart 2, but EVs made in China only represented about 20 per cent of EV sales in the EU in 2023 (and 8 per cent if we consider Chinese brands only).2 Conversely, in 2024 the EU imported more solar panels from China than it installed.3

While clean tech products have not been a key focus for Trump, both country-specific and sectoral tariffs affect them heavily. In sectors where China has still been exporting large quantities of goods to the US, the EU will likely face an even greater inflow of cheap Chinese products than is currently the case. Simulations suggest that the scale of trade diversion under a renewed US–China tariff escalation could be substantial. In a severe scenario, EU imports from China could rise by 7–10 per cent, according to estimates by the European Central Bank (ECB).4

Trade diversion is highly uneven across sectors. In the short run, highly standardised goods, whose demand is highly sensitive to price, are most prone to redirection following a tariff shock.5 This includes goods like solar panels and batteries: China could increase its supply of these goods to non-US markets by nearly 30 per cent, according to estimates.6 Likewise, these sectors are also the most responsive to tariffs. In contrast, complex, regulation-intensive technologies are less sensitive to short-term price shifts, and hence less prone to rerouting. These products include electric vehicles, wind turbine systems and to some degree electrolysers. Their supply chains rely on certification, standards alignment, and high capital investment, which protect them from short-term shocks but also make them harder to rebuild once displaced.

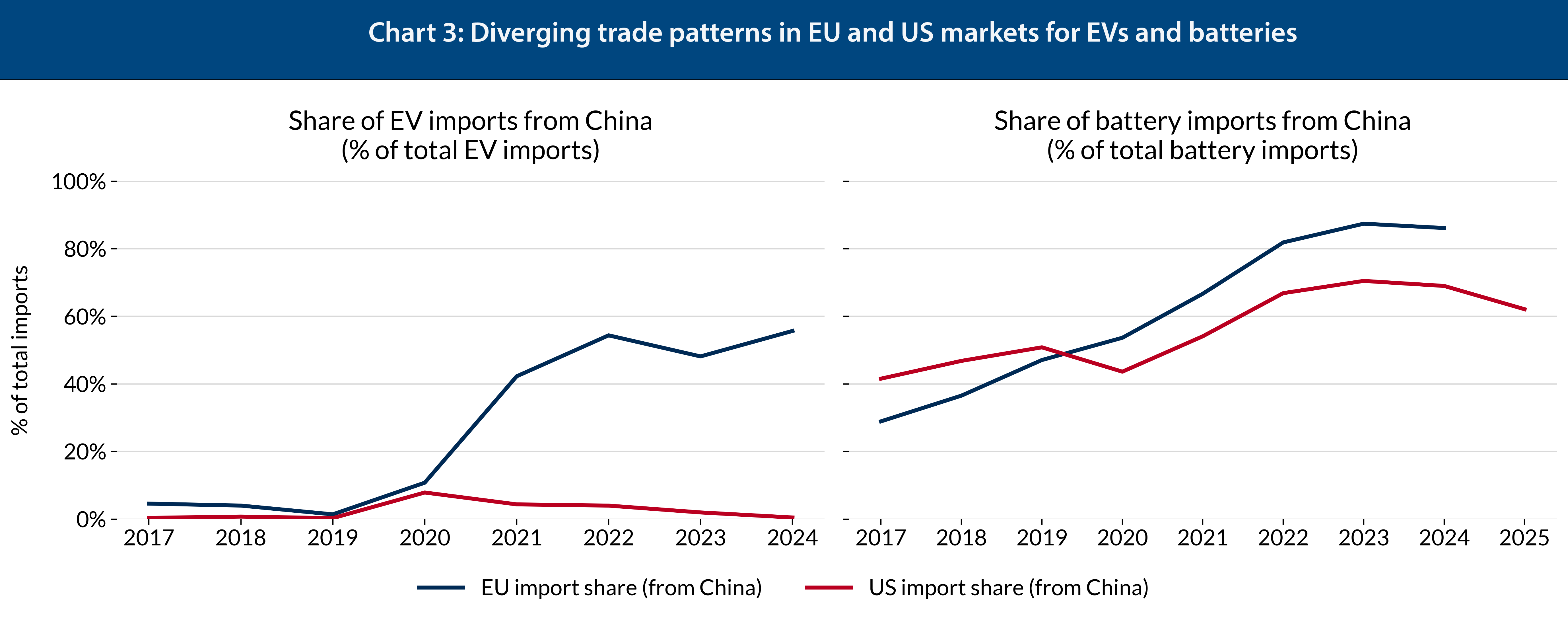

A striking example of trade re-routing in the first US-China trade war was lithium-ion batteries. Batteries are the only clean technology where the US and the EU imported comparable volumes from China ahead of the 2018-2020 trade war. The US did not entirely close its market to Chinese batteries (unlike EVs), but introduced a series of harsher trade restrictions than the EU. As a result, Chinese import concentration in the US declined in 2019-2020 – showing that the US diversified its battery imports in response – while it continued to rise in the EU. Afterwards, import concentration from China picked up again in the US, though at a slower pace than in the EU (Chart 3).

This pattern appears to be repeating itself under Trump 2.0: since the start of 2025, US battery imports from China have fallen sharply while EU imports have continued to rise, hinting at a possible renewed diversion of Chinese supply from the US market towards Europe. As trade redirection towards the EU increases, Chinese export prices are bound to go down even further. There is already some evidence of this for batteries: unit prices of Chinese batteries imported into the EU (in US dollars per kg) declined by approximately 17 per cent between December 2024 and August 2025. While part of this decline reflects technological improvements and lower input costs, the fall was more than three times steeper than in the preceding eight-month period – suggesting that stronger price competition linked to market redirection also played a role.7

2.2 A turnaround in US industrial policy, while the EU slowly crafts its own

The second Trump administration is rolling back US climate policies and cutting down substantially on the industrial policy subsidies that boosted American clean tech manufacturing under Joe Biden’s presidency. This is exemplified by the shift from Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to Trump’s signature budget bill, the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ (OBBB).

Adopted in August 2022, the IRA offered various types of financial incentives over a planned time horizon of 10 years. For manufacturing, this included tax credits for products such as solar energy components, power inverters, batteries and critical raw materials. To boost deployment, the IRA offered purchase incentives for consumers to adopt EVs and heat pumps, as well as subsidies for producing and storing clean energy with solar panels and batteries. These generous support schemes came with a large but hard-to-pinpoint fiscal cost, with overall manufacturing subsidies officially estimated at $72.7 billion for the years 2023-2027.8 This is substantially larger than the EU and member-states have been offering.

But Trump’s OBBB is now entirely stopping some IRA subsidies and is speeding up the phase-out of others.9 Additionally, the Trump administration is actively erecting investment barriers against some clean technologies, including by attacking individual projects in wind energy. The effect is substantial: for US electricity and clean fuels production alone, the OBBB is estimated to reduce cumulative capital investments by $500 billion in 2025-2035.10

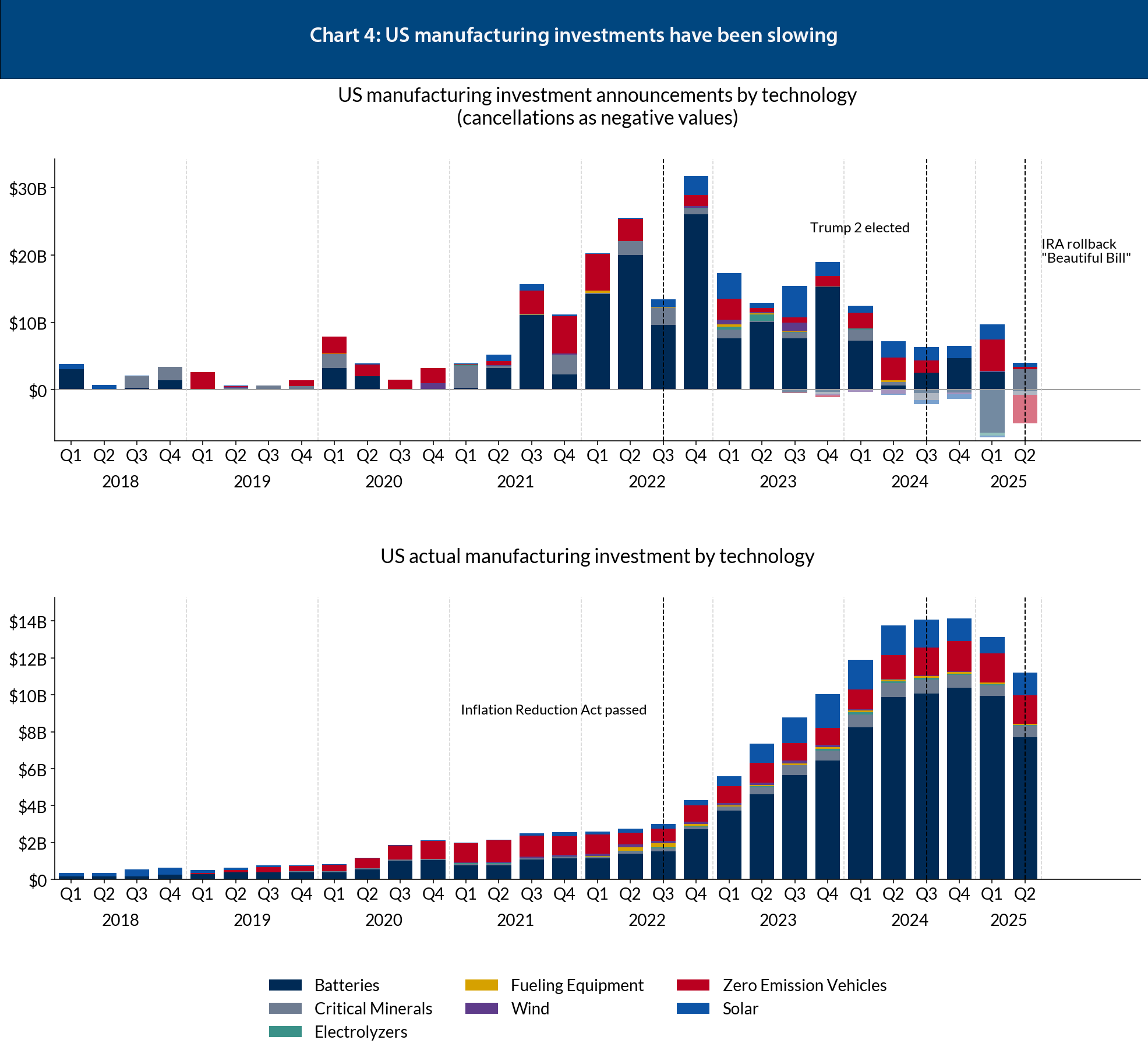

Overall, the new US administration is creating substantial headwinds for EU exporters, as well as some limited opportunities. The new US policies have three key impacts on the US market: First, US demand for many clean technologies has started to fall, and is set to contract further. Second, future US supply of clean technologies will be lower than expected as well. However, the OBBB does not reduce most manufacturing subsidies significantly, so the supply reduction is likely to be less pronounced than the demand reduction (see Chart 4 below). Third, the new tariffs might squeeze China out of the US market in product categories where it is still exporting to the US, possibly providing some opportunities for EU exporters to capture its market share. If US demand for a given technology fell by less than domestic supply and Chinese imports combined, this would represent an opportunity for EU exporters – otherwise, exports to the US are likely to be reduced.

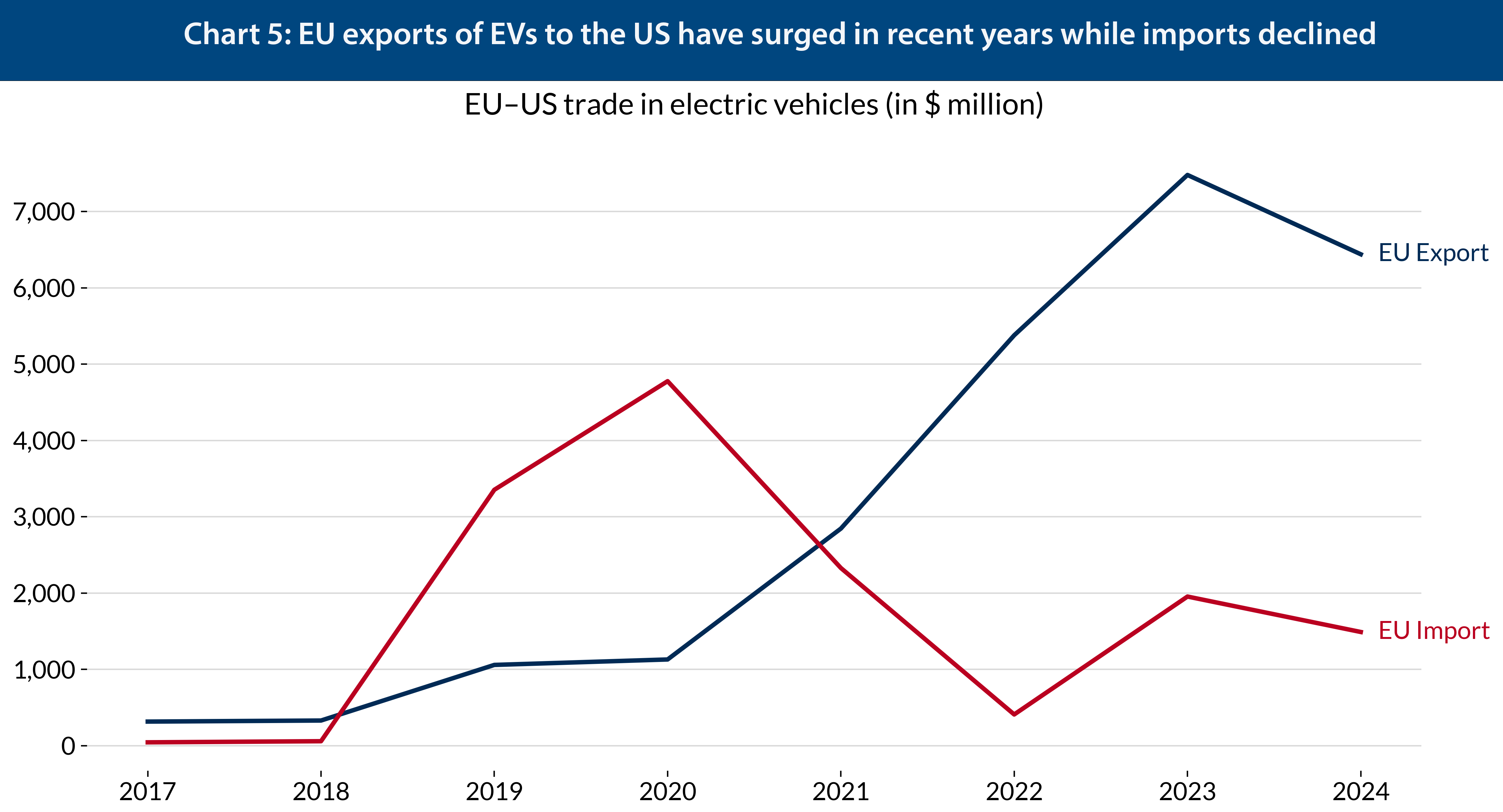

For some EU exports, such as EVs, reduced US demand is probably the dominant effect – and a key drag. US demand for clean tech was boosted substantially by the IRA. For example, the IRA offered an EV tax credit of up to $7,500, which was also available for EU-made EVs (although only for leased vehicles). Given that the US is a key export market for EU-made EVs (see Chart 5), the IRA would have provided crucial demand for EU car makers over the coming years. However, the OBBB has phased out EV tax credits, which will, it is estimated, result in 27-41 million fewer EV sales in 2035, a 20-30 per cent reduction from the current policy scenario.11 On top of that, Trump 2.0 has also used executive orders to reverse some of the supportive EV regulation of the Biden administration, like the vehicle emissions standards, as well as state-level policy initiatives, such as EV mandates in California.

At the same time, the potential for European substitution for Chinese EV exports is marginal. Because of prohibitive tariffs and regulatory restrictions, Chinese EV exports to the United States have already been negligible, at only $389 million in 2023 – barely 2 per cent of total US EV imports. Moreover, US policy has favoured reshoring and continental supply integration in North America (as part of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement) rather than substituting imports from Europe for those from China.12 Additionally, the US is currently on track to double its production capacity to about 6 million EVs per year, while demand is estimated only at 4 million.13 Overall, the outlook for EU EV exports to the US market, relative to the baseline pre-Trump, has deteriorated sharply.

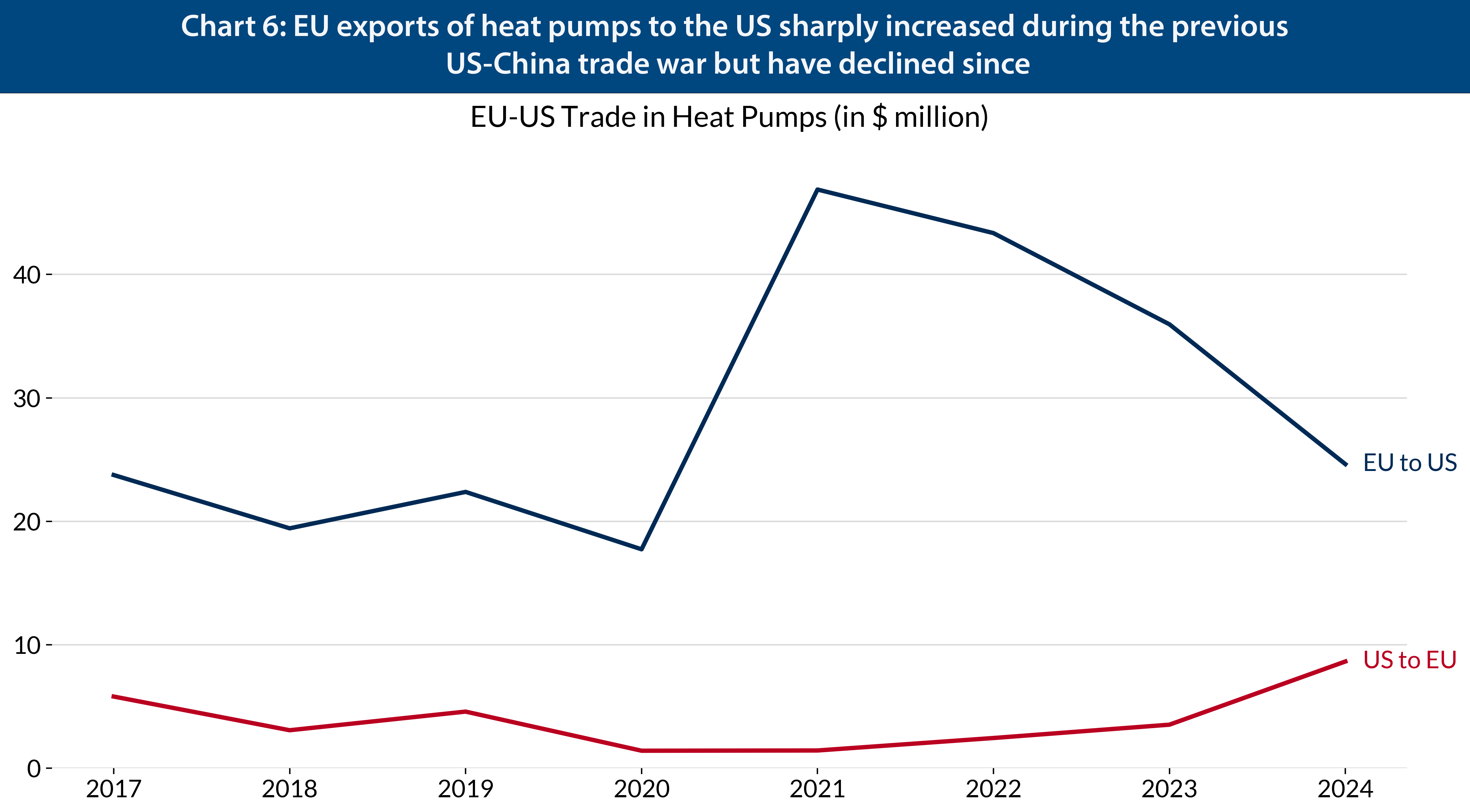

On the other hand, heat pump exports to the US are currently comparatively small, but could present a growing opportunity for EU producers in spite of the US phasing out heat pump subsidies. Because about 40 per cent of the US imports of heat pumps in 2024 came from China, tariffs on these goods would create tangible room for European manufacturers – provided they can match US price points and expand production. Chart 6 shows that European exports of heat pumps to the US rose sharply during the pandemic, after the previous US–China tariff rounds in the first Trump administration. This suggests that European suppliers could increase their export capacity again, especially if Chinese competitors retreated.

For clean energy generation components, the outlook for EU exporters is mixed. With the IRA, subsidies for wind and solar energy were around $30/MWh, totalling approximately $30 billion per year,14 which substantially boosted demand for wind and solar parks. Similarly, the 3 USD/kg unit subsidy for green hydrogen was sizeable. But the OBBB is phasing out solar, wind and hydrogen tax credits much earlier than planned, leading to estimated cuts in renewable energy investment in the US by at least $60 billion in 2028.15

Most of these changes in US subsidies affect EU manufacturers too. Solar panels are the exception, given that the EU does not export many of them anyway. While the market for electrolysers is quite small today, it is likely to grow substantially in the future, with EU producers well-positioned to capture parts of the US market.

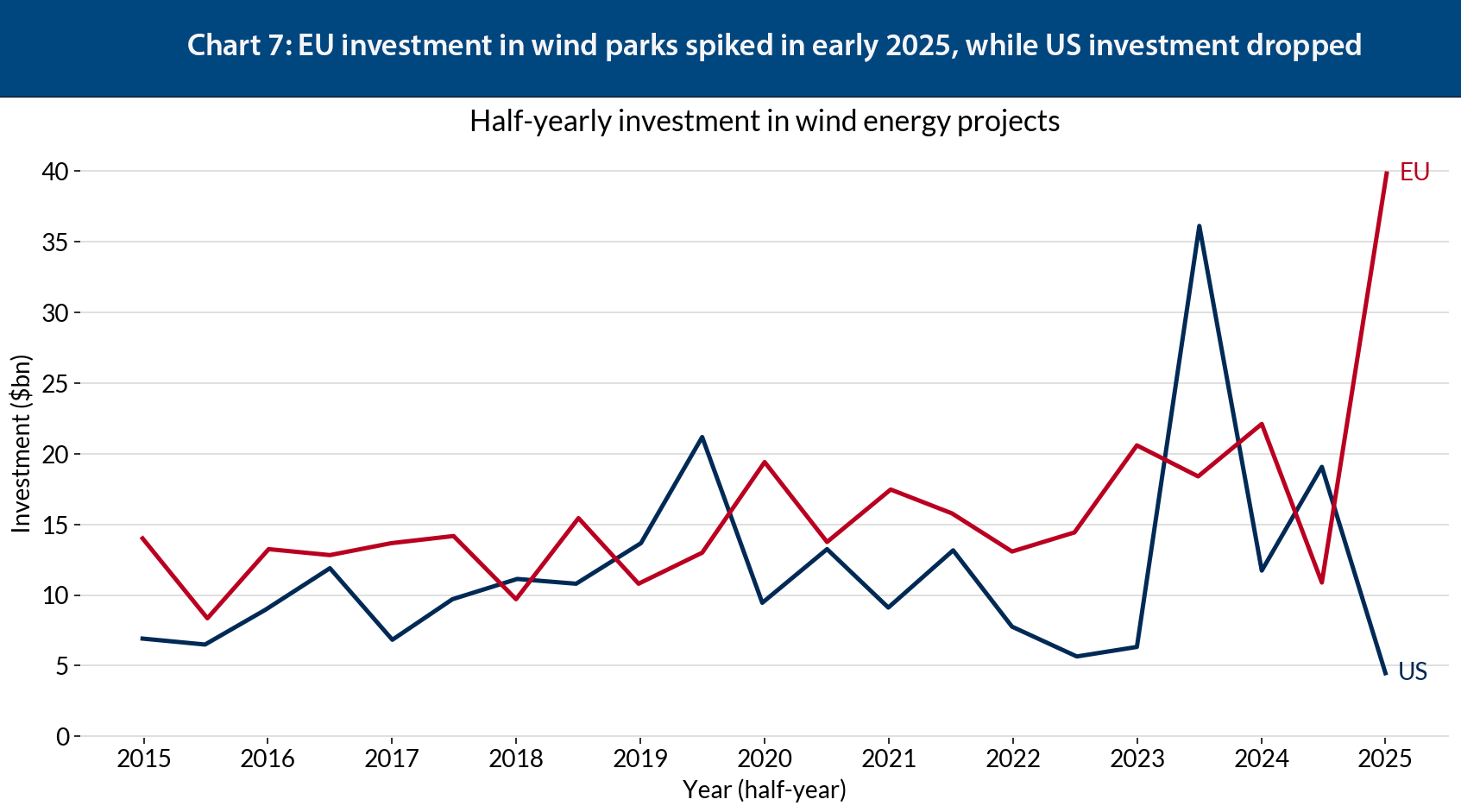

On the other hand, EU exports of wind energy components to the US are likely to decrease in the short term. Wind energy is one of the few strongholds of EU clean tech industry, and EU-based manufacturers benefitted from and supplied products to power the IRA-driven surge of wind park projects in the US. However, the impact on wind energy of Trump’s policy reversal is already evident in the decline in demand for wind energy components. One striking example was the Trump administration’s unilateral halt to the $1.5 billion ‘Revolution Wind’ offshore wind project, for which EU manufacturers supplied most of the high value kit.16 While a federal judge’s decision has since ordered work to resume,17 getting permits for new wind projects will undoubtedly be much more difficult under this administration. Consequently, the export opportunities created by the IRA for wind are mostly gone for now. A silver lining might be that the US retrenchment causes some international wind project developers to shift their investments from the US to the EU, as indicated by recent investment figures for wind parks in Chart 7.

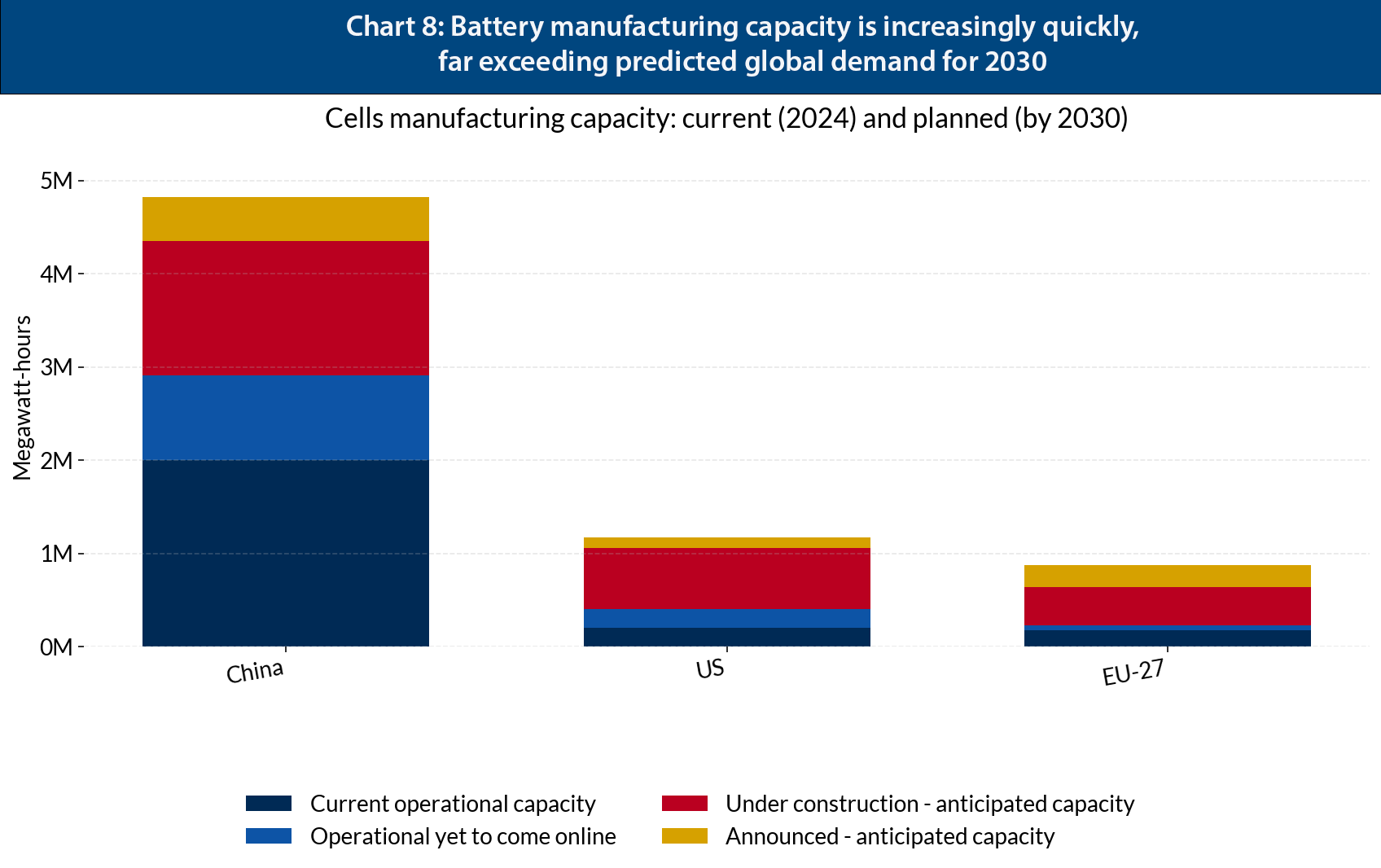

In the battery sector, EU companies will have to compete against the massive domestic production capacities being built in the US (Chart 8). While the evolution of US domestic demand is uncertain given the ongoing policy U-turns,19 the estimated battery production capacity in the US would be largely sufficient to satisfy it, indicating that EU exporters will face fierce competition on the US market. Even though US trade barriers against Chinese batteries are limiting their imports, it will be a challenge for EU producers to capture an increasing market share in the US.

In sum, Trump’s policy reversal has worsened the prospects for exports of key EU clean technologies to the US. This will hit exports of EVs and wind energy equipment particularly hard, because they benefitted from IRA provisions. US domestic capacity for bat-tery manufacturing is growing, so it will be difficult for EU battery producers to seize a large market share. Some smaller industries – such as heat pumps and electrolysers – could benefit from Chinese goods being largely excluded from the US market, however.

3. Policy recommendations

The EU lacks a clear clean tech strategy. In response to the IRA, in mid-2024 the EU adopted the Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA), which set targets for domestic clean tech manufacturing – some ambitious, others unrealistic. However, since then, the EU has continued to slip behind China, instead of catching up with it, in many clean technologies.20 With the Clean Industrial Deal (CID), the EU has correctly identified its problems and the right machinery to tackle them, such as ‘Buy European’ requirements to support the emergence of markets for clean tech, continued carbon pricing, a faster and less bureaucratic regulatory framework, as well as financial support. But whether these instruments are wielded in pursuit of a clear strategy, and with sufficient force, will only be answered in the next one to two years, once legislation is adopted. The medium-term picture is more positive: if a climate-ambitious administration came into office in the US after the 2029 election, US clean tech demand could rebound, to be partly satisfied by EU producers. But as emerging countries start considering tariffs on Chinese exports,21 more Chinese production could be diverted onto European markets.

What the EU needs today is targeted industrial policy to help its clean tech industry weather the current rough patch and position itself for a possible upswing. The Industrial Accelerator Act, to be proposed by the Commission in December 2025, can incorporate many of the necessary measures. This is how these policies should be structured:

1) Step up trade defences against Chinese overcapacity

Deploy tariffs where dumping destroys capacity, not where cheap inputs lower costs. Europe should target trade-defence measures to support sectors most exposed to Chinese price competition, such as batteries. Demand for this type of commoditised good is highly sensitive to price changes, and below-cost imports can quickly wipe out EU producers. By contrast, for solar panels, where global overcapacity is extreme and EU re-shoring would demand unmanageable subsidies, the EU should continue to benefit from low-priced imports to accelerate installation.

Expand European preferences in public procurement – but keep them open to allies. With Chinese exports increasingly redirected toward Europe, European preferences could raise returns and reduce risk for EU firms. This is important for wind and battery manufacturing equipment – technologies that are both central to Europe’s clean tech value chains and highly exposed to Chinese price pressure. Clean tech tenders should favour EU-based supply chains by weighting carbon footprint, recyclability and – for tackling import concentration on China – supply-chain diversification in award criteria. This would keep the EU approach to procurement open to partners meeting equivalent standards, while keeping non-allies – particularly China – out of tenders for selected products. The European Commission should activate the International Procurement Instrument when European businesses face unfair barriers abroad in procurement, allowing Europe to penalise or exclude bidders from countries that do not reciprocate market openness.

Introduce clear obligations for foreign investment in strategic sectors to protect critical capacities and avoid future dependency. Foreign direct investment (FDI) can help expand Europe’s manufacturing capacity, but it does not automatically create local jobs, technology transfer, or diversified supply chains. To ensure that it does, the EU should screen investments in strategic industries. Such FDI should be conditional on investments in local R&D, workforce training and knowledge sharing. This would ensure that foreign capital builds European capabilities rather than increasing dependency on a single supplier. These tools should complement anti-dumping and subsidies counter-vailing tariffs, including anti-circumvention measures, as well as decisive measures under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation, helping to maintain a level playing field.

2) Offset the US demand shock in sectors in which Europe is competitive

Provide regulatory and demand-side stability in sectors of European industrial strength. A mix of policies could buttress EU clean tech production in the face of weaker US demand. In wind energy, such policies could include multi-year auction pipelines, predictable contracts for difference (CfDs) that guaranteed developers a fixed revenue and reduced exposure to volatile electricity prices, and accelerated permitting for wind parks. In the automotive sector, the EU should stick to the 2035 phase-out of internal combustion engines, harmonise consumer incentives across member-states, and accelerate the buildout of charging infrastructure for EVs. Policy certainty would give firms the confidence to invest through the current geopolitical turbulence.

For consumer-facing technologies like heat pumps, demand stability is equally vital. Stable regulatory frameworks, subsidies, accessible financing and predictable public-sector procurement – for schools, hospitals, and renovation of public buildings – is needed to create steady demand for these emerging technologies. The EU should also top up national subsidies with European funding, drawing on instruments like the planned European Competitiveness Fund and Horizon Europe, ensuring predictable resources and a truly common industrial effort rather than fragmented national initiatives.

3) Boost supply-side support for strategic emerging industries

Expand Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEIs) and simplify access for emerging technologies. IPCEIs are state-aid regulatory instruments that ena-ble member-states and firms to co-operate on large, cross-border industrial investments considered strategic. Yet complex approval procedures slow their impact, and so far they only exist for a limited number of sectors. To maximise their potential, the EU should: (1) continue its efforts to simplify access and reduce procedural burdens, enabling faster decision-making and project deployment; (2) broaden coverage, set by member states via the Joint European Forum for IPCEIs, to include technologies in which European producers can grow and lead – for example heat-pumps and emerging battery technology (such as sodiumion types); and (3) make IPCEIs eligible for addi-tional EU funding (via instruments like the European Competitiveness Fund) to achieve the size and scope needed for truly pan-European industrial scale. At present, projects rely mainly on national budgets, which constrains their scale and excludes countries with less fiscal capacity. EU co-financing could support larger projects where potential and European benefits are highest.

Complement national aid frameworks with EU-level production support. The EU’s new Clean Industrial State Aid Framework (CISAF) allows member-states to provide support to clean tech manufacturing, but it does not bridge differences in fiscal capacity between them. Moreover, it does not have the time horizon to deliver predictable, long-term support, and only allows investment aid, not production-linked subsidies. But the latter could help Europe’s battery and hydrogen industries remain competitive during ramp-up until uptake and learning curves reduce costs. This is particularly relevant for batteries, where high electricity and input costs have been important drivers behind the erosion of Europe’s cost competitiveness.

4. Conclusion

EU clean tech is facing a double shock – strong Chinese competition fuelled by technological innovation and overcapacities, and stagnating demand in the US due to an abrupt policy reversal. Combined with an uncertain policy outlook at home, these shocks threaten clean tech manufacturing, even though the EU starts from a strong industrial base.

Beyond short term impacts on EU exports, US retrenchment opens possibilities for the EU to position itself better globally. At least for the next few years, the US will be a less prominent player in the global race for clean tech. Yet this race will go ahead: the EU should seize this opportunity to position itself as a powerhouse in a growing market, as clean tech manufacturing is one of the few economic domains where the EU can surpass the US and resist China’s manufacturing take-over. As this paper outlined, the EU needs a coherent strategy to become a global clean tech leader: targeted trade defence measures, EU-level industrial support that complement national measures, and consistent climate policy signals.

2 ACEA, ‘Fact sheet: EU-China vehicle trade’, June 12th 2024.

3 EUPD Group, ‘European Solar Market 2024-2025: Balancing Growth, Challenges and Opportunities’, January 13th 2025.

4 Lukas Boeckelmann, Lorenz Emter, Vanessa Gunnella, Karin Klieber and Tajda Spital, ‘China-US trade ten-sions could bring more Chinese exports and lower prices to Europe’, ECB Blog, July 30th 2025.

5 Christoph E. Boehm, Andrei A. Levchenko and Nitya Pandalai-Nayar, ‘The Long and Short (Run) of Trade Elasticities’, April 2020, revised November 2022.

6 Julian Hinz, Isabelle Méjean and Moritz Schularick, ‘The consequences of the Trump trade war for Europe’, Kiel Institut, April 2025.

7 The unit price is calculated as import value divided by import volume in kg, with COMTRADE data.

8 Nicholas E. Buffie, ‘The section 45X advanced manufacturing production credit’, Congressional Research Service, November 7th 2024.

9 Ed Crooks, ‘What the “big beautiful bill” means for US energy’, Wood Mackenzie, July 11th 2025.

10 Jesse Jenkins, Jamil Farbes and Ben Haley, ‘Impacts of the one big beautiful bill on the US energy transi-tion – summary report’, REPEAT Project, July 3rd 2025.

11 Ben King, Hannah Kolus, Michael Gaffney, Nathan Pastorek and Anna van Brummen, ‘What passage of the “One big beautiful bill” means for US energy and the economy’, Rhodium Group, July 11th 2025.

12 Mary Lovely, ‘Manufacturing resilience: the US drive to reorder global supply chains’, Aspen Institute, November 8th 2023.

13 BloombergNEF, ‘Global electric vehicle sales set for record-breaking year, even as US market slows sharply, BloombergNEF finds’, June 18th 2025.

14 Congressional Budget Office, ‘Business Tax Credits for Wind and Solar Power’, April 11th 2025.

15 Jesse Jenkins, Jamil Farbes and Ben Haley, ‘Impacts of the One Big Beautiful Bill on the US energy transition – summary report’, REPEAT Project, July 3rd 2025.

16 Lisa Friedman, Brad Plumer and Maxine Joselow, ‘Trump administration orders work halted on wind farm that is nearly built’, The New York Times, August 22nd 2025.

17 John Moritz, ‘Revolution Wind work goes on as Trump administration misses deadline’, CT Mirror, November 24th 2025.

18 Simon Mundy, ‘European green investment stands to gain at the US’s expense’, Financial Times, August 27th 2025.

19 Rhodium Group, ‘Global Clean Investment Monitor: Electric Vehicles and Batteries’, June 18th 2025.

20 Philipp Jäger, ‘Lost in implementation? The Clean Industrial Deal demands urgent and bold delivery’, Jacques Delors Centre, June 20th 2025.

21 BloombergNEF, ‘Clean Energy Trade and Emerging Markets: the Impact of Tariffs on the Energy Transition’, October 30th 2025.

Download full publication

Download press release