Reconciling UK migration policy with the energy transition

- In the recently published immigration white paper, the British government promised to reduce net migration by only offering skilled worker visas to applicants with jobs that pay over £38,700 a year, and which require a degree or equivalent qualification.

- That policy is in tension with two of its other missions – to build 1.5 million new houses by the end of the parliament in 2029, and to keep Britain on track for net zero carbon emissions by 2050. The net zero goal will require increasing numbers of workers, especially in construction, to decarbonise buildings and transport.

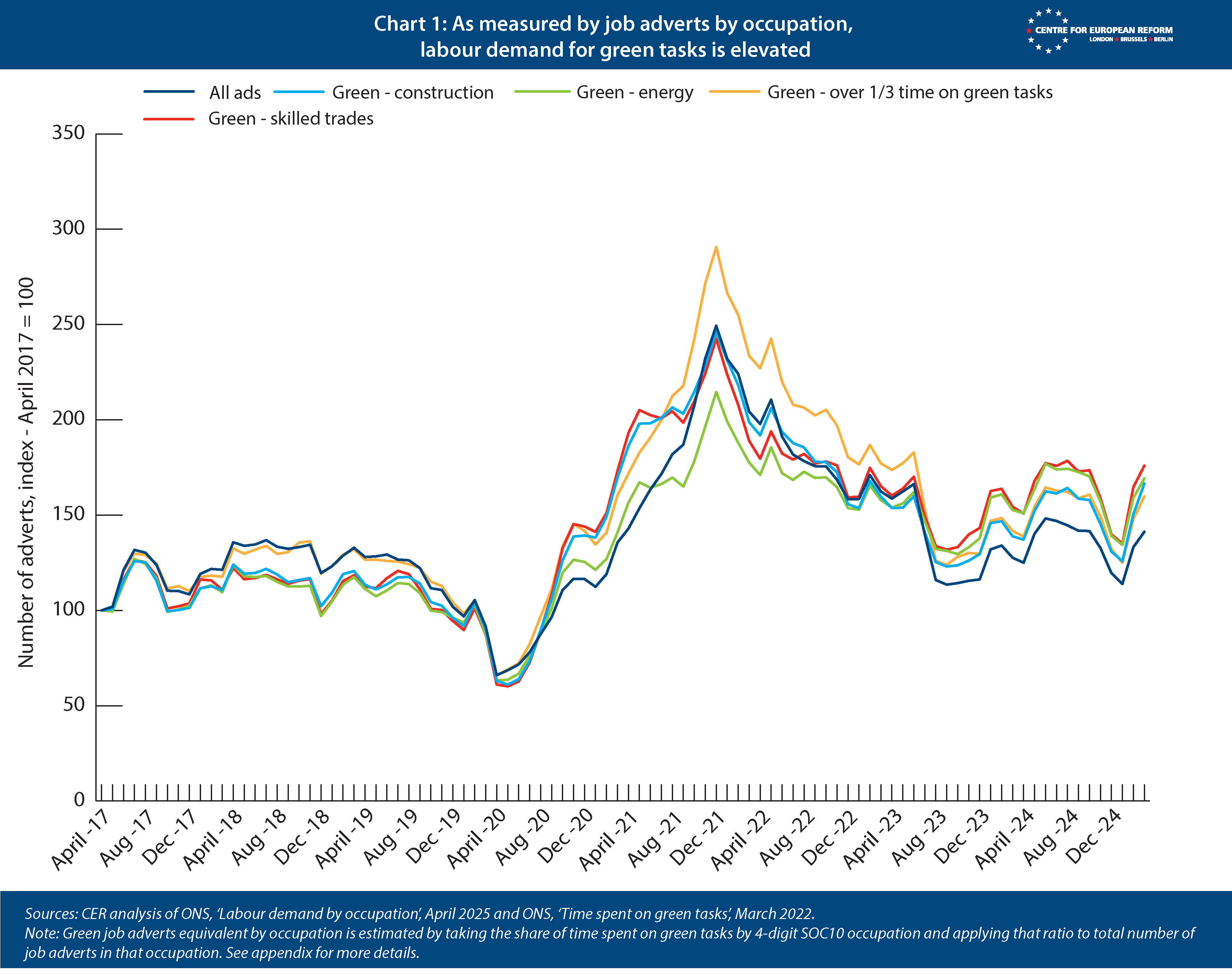

- The previous migration regimes – free movement and limited visas for non-Europeans up to 2021, and then a relatively liberal regime for all foreign workers after – largely delivered enough workers to fill green jobs. But there are signs that labour demand for green jobs is growing, as measured by the number of job adverts, especially in energy, construction and skilled trades, such as double-glazing installers.

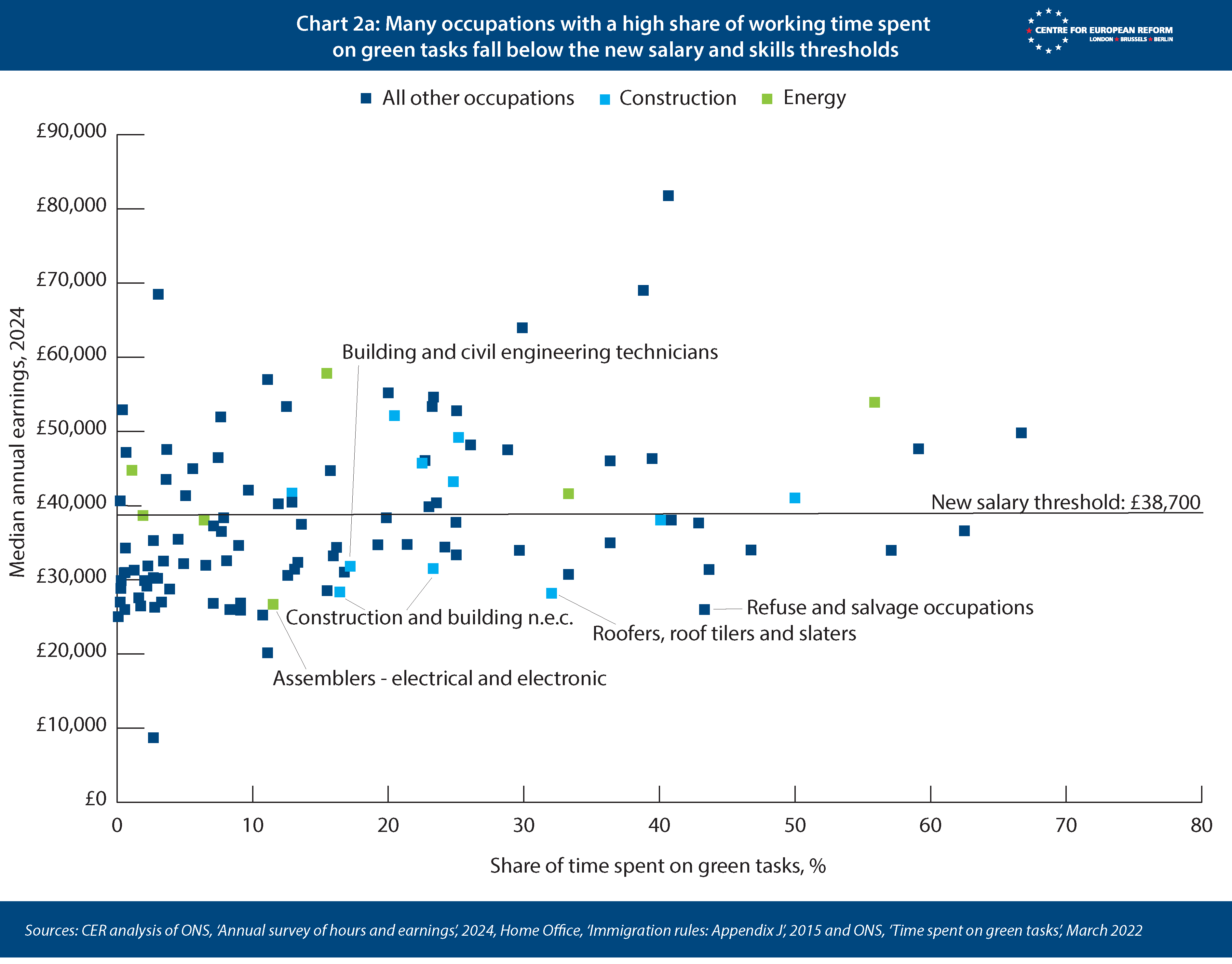

- Many green occupations, especially in construction and skilled trades, do not meet the new salary and skills thresholds. Currently, around 260,000 foreign-born workers in jobs in which more than a third of working time is spent on green tasks would be ineligible under the government’s proposed salary and skills thresholds. Because it is physically demanding work, builders and skilled tradespeople can find it difficult to recruit enough workers. There is a risk that the salary and degrees thresholds tighten labour supply in these sectors too much, undermining the government’s housebuilding and net zero aims.

- The government should show flexibility in providing visas for workers needed to fulfil its missions. Under the plans outlined in the white paper, it will maintain a ‘temporary shortage list’ of occupations that are important to its aims, but in which labour shortages are appearing. That list will have lower salary or skills thresholds. However, given the fact that visa-holders can only switch to occupations that meet the higher thresholds, there is a risk that workers on the shortage list get taken advantage of by their employers, with bad working conditions and no career progression. If these problems arise, the government should consider reducing salary and skills thresholds for all workers, prioritising investment needs over its desire to cut immigration.

Net migration surged to a height of 900,000 in the summer of 2023, before falling to around half that level by the end of last year, as white-hot labour demand was cooled by higher interest rates and vacancies fell, and after Rishi Sunak’s government tightened migration rules. Labour has decided to go further: in May 2025, the Starmer government set out plans for stronger immigration controls.

The proposals include maintaining the Sunak government’s higher salary threshold for jobs eligible for skilled worker visas to £38,700, and raising the minimum skill level from qualifications equivalent to an A-level to a degree or equivalent. To get indefinite leave to remain in the country, immigrants will have to live and work for ten years, up from five currently. Some occupations may be put on a ‘temporary shortage list’ if the Migration Advisory Committee, an independent body that advises the government on immigration policy, recommends an exemption and the industry involved demonstrates to the government that it is making efforts to recruit domestically and to train potential workers.

This move has implications for the government’s other ‘missions’, such as raising growth, fixing the NHS, building 1.5 million new homes by the end of the parliament in 2029, and keeping on track for net zero by 2050. This policy brief focuses on the last of these missions, and uses data on immigration and green jobs to ask three questions:

- Did the previous immigration regimes – free movement and the visa system for non-EU nationals before 2021, and the relatively liberal regime that replaced it – provide enough green workers?

- Which green occupations will fail to meet the government’s new salary and skills thresholds?

- What are the immigration policy options if the new rules undermine the net zero mission?

The brief provides a new analysis of the extent to which foreign-born workers have been employed in occupations that are important to the environment and the energy transition, as the electricity system is decarbonised and heating and transport shift from fossil fuels to electricity. It shows which green occupations will not be eligible for visas under the government’s new immigration rules, and considers which jobs will be difficult to incentivise domestic workers to do. It concludes with the immigration policy options to ensure Britain’s energy transition gets the workers that it needs.

Did the previous immigration regimes provide enough green workers?

Labour’s economic policy is now fairly clear. It will continue the previous government’s plans to raise public investment – repairing hospitals, schools and roads, and improving public transport – in order to improve a frayed public realm. It will combine that with tight spending for the public services and welfare, outside the NHS. Investment will be funded by borrowing, and relatively loose fiscal policy will keep interest rates higher than they were in the 2010s. Tighter current spending will be paid for with tax rises on employment, income (via ‘fiscal drag’, with income tax rate thresholds not rising with inflation) and wealth.

The government must balance its public investment mission with the investment needs of the private sector, which it expects to deliver its missions to build new homes, cut carbon emissions and reduce energy costs through efficiency measures. The economics of net zero are about higher investment – largely by businesses and households, but driven by regulation, tax and subsidy by government – in order to rapidly cut fossil fuel use and raise energy efficiency, especially in buildings and transport. Higher interest rates mean higher borrowing costs to fund that investment.

The other balancing act for the government is in the labour market. The government is strengthening workers’ rights, raising the national minimum wage, and requiring employers to pay higher national insurance contributions. These moves may weaken employers’ demand for workers. Tighter immigration controls, especially in middle to low-skilled occupations, may reduce labour supply. If the labour pool is curtailed too much, it may be difficult to fulfil its missions to build new, more energy-efficient homes, insulate and electrify heat in existing ones, and construct renewable energy plants and larger electricity grids.

Tighter immigration controls, especially in middle to low-skilled occupations, may reduce labour supply.

The contrast with the economic challenges of the 2010s could not be starker. Then, very low interest rates meant that the government had no difficulty in funding more public investment (although it chose not to do so) and the trade-off between public and private investment was less acute. High employment rates did not constrain employment growth, because free movement allowed immigrants to take jobs in occupations that few Britons wanted to do.

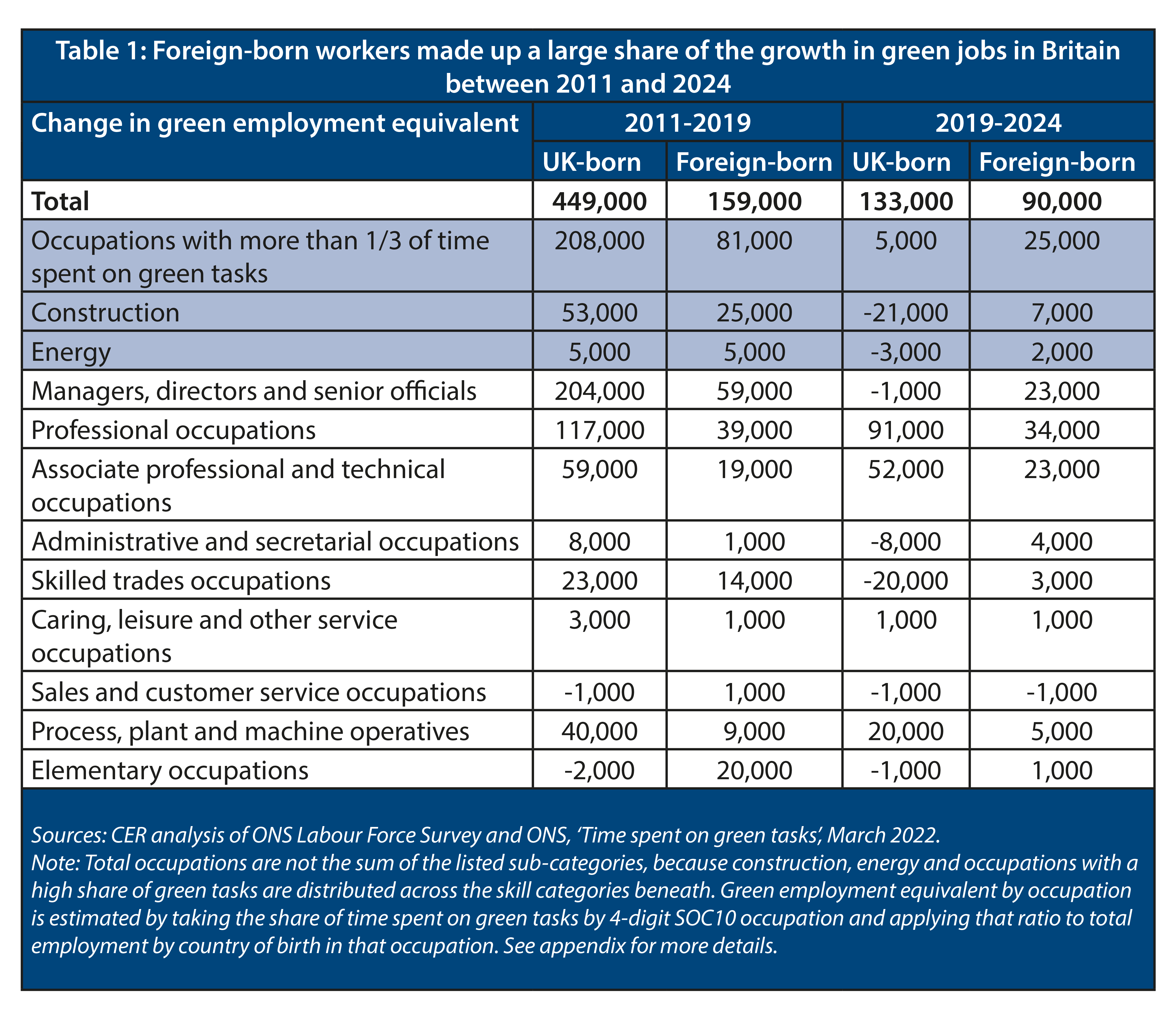

As more work was put into the energy transition in the 2010s, foreign-born workers moved into occupations where green tasks were a significant part of the job. Table 1 sets out the growth in green employment across different groups of occupations between 2011 and the eve of the pandemic in 2019, and between 2019 and 2024, when free movement between Britain and the EU ended, the relatively liberal migration regime replaced it, and net migration to the UK surged.

Between 2011 and 2019, foreign-born workers made up about a third of total new green employment. There were higher shares of employment growth in construction, energy, and occupations in which over one-third of working time is spent on green tasks. After the pandemic and Brexit, foreign-born workers took an even greater share of green employment growth overall. And in construction, energy and skilled trades, such as electricians and double-glazing installers, growing foreign-born employment only partially offset falling employment among the UK-born.

After the pandemic and Brexit, foreign-born workers took an even greater share of green employment growth overall.

The fall in UK-born employment in green construction is part of a wider fall in construction employment, which has dropped by 11 per cent since its peak in the first quarter of 2019.1 With energy, it is one of the key sectors for decarbonisation, especially in the next decade as heat pumps need to replace gas boilers, and homes need to be insulated. Construction is a more labour-intensive sector than energy; it is difficult to replace builders and trades-people with machinery and other forms of capital, so productivity growth is slow.

However, we should not conclude that the new migration regime after 2021 was not liberal enough to offset falling UK-born employment in energy, construction and skilled trades. The main driver of the fall in construction over 2022-2023 was the jump in interest rates over this period: because production is sensitive to changes in the cost of capital, higher interest rates slowed down construction. As a consequence, labour demand fell, but the relatively low salary and skill thresholds in the post-2021 migration rules did allow falling UK-born employment to at least partially be offset by immigration.

According to job adverts data, it appears that green construction demand is recovering. Chart 1 shows that, after the huge mismatch in labour supply and demand after the pandemic, the total number of job adverts stabilised after the summer of 2023. But there appears to be structurally higher demand for employment in green jobs overall (as defined by over a third of working time being spent on green tasks). That is true of green jobs in energy, construction and skilled trades. This is not surprising, given the renewed push to decarbonise energy and buildings.

Looking ahead, as the economy adjusts to higher interest rates, and the government continues to push on with its housebuilding and net zero missions, we can expect labour demand for green jobs to remain elevated. Will the government’s new migration regime hinder those ambitions?

Which green occupations will fail to meet the government’s new salary and skills thresholds?

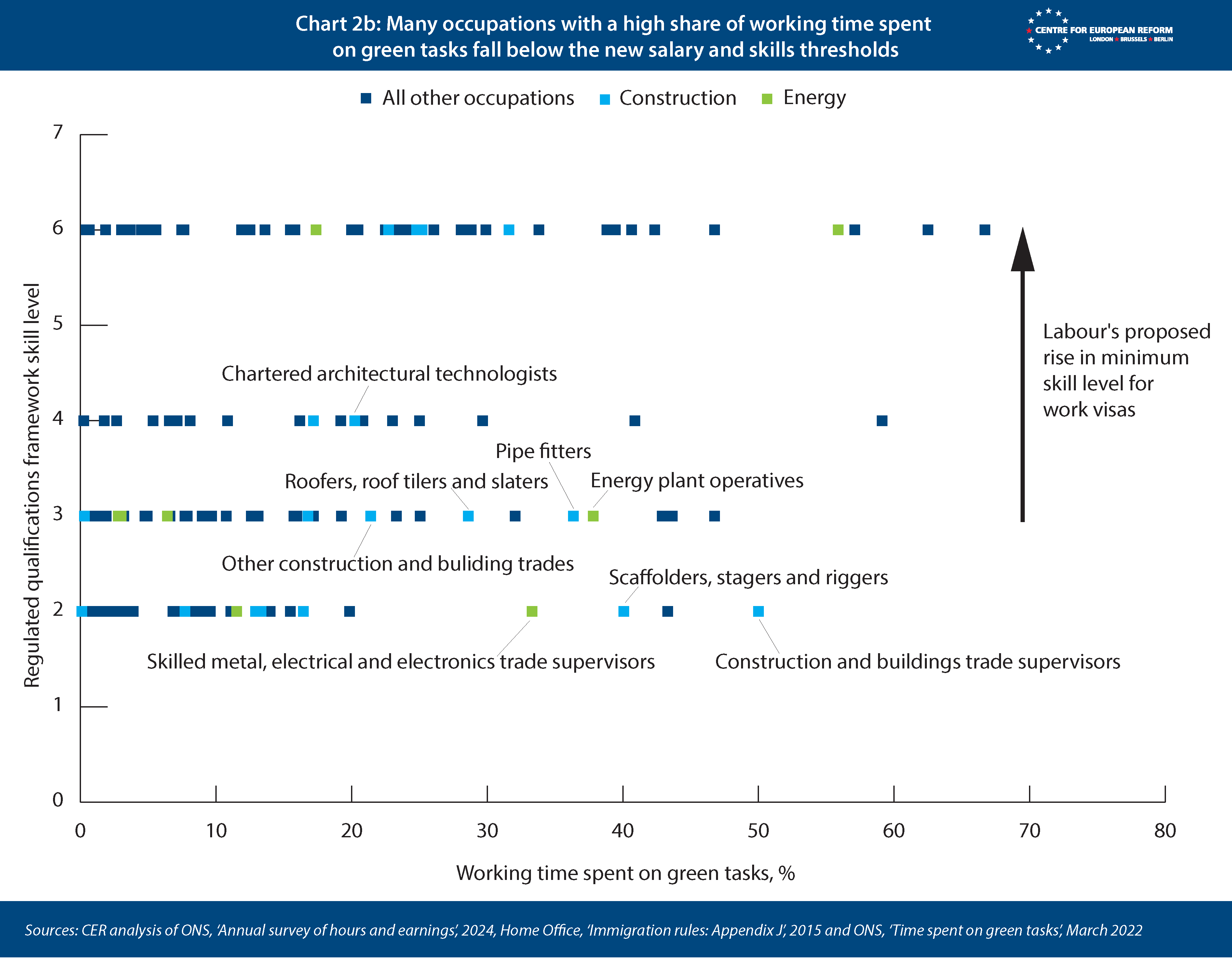

As noted above, the Sunak government raised the salary threshold for a skilled worker visa from £25,600 to £38,700 a year. In its white paper, Starmer’s government has promised to keep that rate, and to raise the skills requirement from the equivalent of an A-level to the equivalent of a degree. There are a few construction jobs that are currently on the ‘immigration salary list’, which allows visas for jobs paying less than the salary threshold: bricklayers, roofers, carpenters and building retrofitters. Labour has pledged to make that list temporary, and to press employers to do more to employ and train domestic workers.

As Chart 2 shows, there are many occupations with a high share of working time spent on green tasks with salaries and skill levels below the thresholds. In 2024, there were 465,000 foreign-born workers currently employed in jobs in which more than a third of working time is spent on green tasks. 260,000 of them would be ineligible for work visas under Labour’s proposed immigration rules. The share of foreign-born workers who fail to meet the salary and skills thresholds is particularly high in construction and in jobs planning and conducting environmental clean-up (but in the latter case, the number of people employed in those occupations is small). Many immigrants are young and less likely to be paid the median salary in their occupation, so there is a risk that the pipeline of new workers meeting the new requirements will be insufficient and not enough domestic workers will be willing to take their place.

It is likely that labour demand in the construction sector will rise in the future. Construction is labour-intensive and has a lot of employee turnover, because the work is physical and seasonal. Given that the government’s aim is to expand housebuilding and decarbonise buildings concurrently, the sector is most at risk of labour shortages as a result of the government’s immigration proposals. Forecasting the number of workers needed to achieve the government’s aims is difficult, but according to the Construction Industry Training Board, the industry needs around 250,000 more workers to deliver 1.5 million new homes.2 The energy transition will also become more labour-intensive over time, as emissions from buildings and transport are harder to abate without significantly more workers.3

The construction sector is most at risk of labour shortages as a result of the government’s immigration proposals.

What are the immigration policy options if the new rules undermine the net zero mission?

The immigration white paper is vague on how the government, with recommendations from the Migration Advisory Committee, will determine which occupations should stay on the ‘temporary shortage list’. If the industry concerned is taking steps to recruit and train domestic workers and the occupation is important for other areas of government policy, then it might go on the list. The government will set up a Labour Market Evidence Group, consisting of officials from different government departments and the Migration Advisory Committee, to provide evidence to ”key sectors” that bring in a lot of foreign workers, which the Group should use to produce “a workforce strategy that relevant employers will be expected to comply with”.4

It may be that wages in green jobs will rise if labour supply is constrained by the new immigration rules. Automation in some sectors may help, especially the manufacturing of green technology, although those technologies can also be imported. Most green jobs are in the services sector, in which automation is harder. Higher wages, even in physically demanding construction, would bring in more workers from other sectors.

It may be that wages in green jobs will rise if labour supply is constrained by the new immigration rules.

However, studies of how much immigration reduces wages have found small effects. One Bank of England study found that the apparent small reduction in wages in the skilled production sector (which includes construction) as a result of immigration was almost entirely determined by the fact that immigrants tend to be younger and earn less than the UK-born, thereby dragging down the average. The study found a clearer cause-and-effect relationship, albeit small, in low-skilled services, which includes hospitality and warehousing, but there are fewer green jobs in this sector.5 This suggests that wages are unlikely to rise much if labour shortages arise from fewer immigrants: consumer demand for green products would fall if wages and prices rose. That would undermine the government’s aim to drive up output.

What about more training of domestic workers? At present, large employers with a pay bill of over £3 million pay a levy to fund apprenticeships in their industry (apprentices funded by the levy can be employed by small businesses). One possibility might be to provide more co-funding by government, or to raise the money that industrial sectors must pay, in order to fund more training. Another is to allow the funding to be spent on shorter training courses for workers entering the industry or to retrain existing ones, as opposed to lengthier apprenticeships. The risk is that the money ends up being spent on training that employers would have done in any case, or concentrated on older workers rather than younger ones, who might leave for another employer who gets the benefit of the training provided. And in construction, which is a sector with a few volume housebuilders and a lot of smaller businesses, such workforce planning will be challenging. That is even truer of skilled trades, a sector in which many workers are self-employed. It is unlikely that more training will deliver the construction workforce needed on its own.

If labour shortages in green occupations do arise as a result of tighter immigration controls, the government has a few options.

- Offer ‘green visas’. These would allow immigrants to take up jobs in green occupations – or there could be specific visas for construction and skilled trades, given the overlap with the housebuilding target. The downsides of this option are clearly shown by the failure of the social care visa route, which Labour scrapped in May 2025, citing poor working conditions for immigrants in that sector and examples of outright abuse.6 Visas that are tied to particular occupations are a recipe for exploitative working practices by employers, because workers cannot easily move to another industry. In social care, that led to very long hours, workers not getting paid for the time spent travelling between their clients’ homes, and in some cases, would-be migrants paying illegal recruitment fees in their home country that they then struggled to pay back. Separate visa schemes for construction or less-skilled green jobs might lead to the same problem. And the risk of exploitation would be made more acute by the government’s plans to increase the length of time before an immigrant worker can get indefinite leave to remain, and therefore the ability to freely choose their occupation, from five to ten years.

- Put more occupations on the shortage list, if the skills and salary thresholds are too high to deliver the workers needed. That might cause similar problems. Currently, people with skilled worker visas can shift to another job and update their visa if it meets the thresholds. But because the salary and skills thresholds have risen so much, that will be difficult for migrant workers on the shortage occupation list to do, and they might remain trapped in industries that exploit their lack of ability to move into another one.

- Allow visa-holders on the ‘temporary shortage list’ to move freely to another occupation, even if it does not meet the salary and skills thresholds. Given the high turnover in construction employment, it might mean that many migrant workers move quickly to other jobs outside the sector. However, that would provide some pressure on employers to provide decent working conditions to retain staff.

- Reduce salary and skills thresholds across the board. That would prevent immigrants from being stuck with bad employers. It would be a u-turn for the government, and would raise net migration. But if the lack of skilled workers is undermining net zero and construction missions, and if the government does not want workers to be taken advantage of by employers, it will have to choose.

None of these options is perfect, but given the failure of the social care visa, it would make sense for the government to allow migrant workers to switch industries after a period, if they decide to provide more visas to ease labour shortages, or to reduce salary and skills thresholds across the board.

Conclusion

The UK is ageing, and to ensure that its population remains stable the Migration Advisory Committee estimates that net migration of 120,000 people a year will be needed.7 This suggests that net migration can be reduced from its current level before it starts to reduce employment overall. Yet that will not prevent labour shortages from appearing in some industries, especially those like construction where there are limits to the number of UK-born workers who are willing to take up jobs. The government’s net zero and housebuilding missions may be imperilled by its determination to curb immigration.

The government’s net zero and housebuilding missions may be imperilled by its determination to curb immigration.

The government is trying to drive up investment in both the public and private sectors, while raising taxation on employment and reducing labour supply from overseas. The UK labour market is relatively weakly regulated compared to many European countries, and taxes on employment remain lower. But the risks to its housebuilding and net zero missions are clear, and the government should ensure that its migration policy enables its other missions to be achieved.

Appendix

This paper uses two methods to estimate green jobs and migration flows into those occupations, and labour demand for green workers.

The first is a measure of ‘green employment equivalent’. For that measure, we use ONS research on the amount of time workers across four-digit standard occupational codes (SOC 2010) spend on green tasks.8 That is itself based an annual survey in the US, whose occupation categories have been translated into the international standard. The ONS data is only available to 2020, so we extrapolate the data forward to 2024, based on its annual growth rate. We then use the ONS Labour Force Survey, which provides details on workers’ country of birth as well as their occupation, to estimate changes in employment by nationality between 2011 and 2019, and 2019 and 2024. The ‘green employment equivalent’ measure is the number of workers in each occupation, multiplied by the ratio of time spent on green tasks.

The ONS dataset on time spent on green tasks is experimental, and given the fact that it is based on US survey data, we cannot be sure that the amount of time spent on green tasks in the UK is the same. As for the Labour Force Survey, estimates of workers who were born outside the UK might be undercounted, as there have been problems with lower response rates among migrant groups.9 However, as a check, we compared the LFS data on the change in employment by nationality between 2019 and 2024 to Home Office administrative data of the number of visas issued by occupation between 2021 and 2023. The correlation coefficient was 0.7, suggesting that the LFS figures are reasonably close to reality, especially when aggregated into larger occupational groups, as we do in Table 1 above.

The second is a measure of ‘green job adverts’. Here, the ONS collects data on the number of adverts posted monthly by occupation. Again, we multiplied that number by the ratio of the time spent on green tasks by occupation, to arrive at a measure of labour demand for green workers.

For all data used in this publication, please contact the author via the CER website.

2: Construction Industry Training Board, ‘Over 250,000 extra construction workers required by 2028 to meet demand’, May 2024.

3: See for example, Julian McCoy and others, ‘Labour implications of the net-zero transition and clean energy exports in Australia’, Energy Research and Social Science, June 2024, and Joris Bücker and others, ‘Employment dynamics in a rapid decarbonization of the US power sector’, Joule, February 2025.

4: HM Government, ‘Restoring control over the immigration system’, May 2025.

5: Stephen Nickell and Jumana Saleheen, ‘The impact of immigration on occupational wages: Evidence from Britain’, Bank of England, December 2015.

6: ‘Flawed UK visa scheme led to ‘horrific’ care worker abuse, says watchdog’, The Observer, March 16th 2025.

7: Migration Advisory Committee, ‘Net migration report’, May 2025.

8: ONS, ‘Time spent on green tasks’, March 2022.

9: Adam Corlett and Hannah Slaughter, ‘Measuring up? Exploring data discrepancies in the Labour Force Survey’, Resolution Foundation, August 2024.

John Springford is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

June 2025

Download full publication

This paper has been supported by the European Climate Foundation. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies with the author. The European Climate Foundation cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained or expressed therein.