Resilient growth: Aligning productivity and security

- Europe’s economic model has become more vulnerable as productivity growth stalls and geopolitical competition intensifies.

- State-supported competition from China and renewed US protectionism have increased Europe’s exposure to external shocks – especially where supply chains are concentrated abroad.

- The European Competitiveness Fund (ECF) constitutes one of the EU’s most recent responses. The ECF should primarily be used to boost Europe’s growth through innovation – but the Commission sees economic security as one element of the bloc’s competitiveness, meaning some funds are likely to be used for addressing risks rather than maximising Europe’s opportunities.

- Yet the proposal is both too broad – it lacks a clear framework to prioritise harmful dependencies and find the most growth-compatible way to address them – and too narrow, by not systematically contemplating support for trade diversification or improvements to Europe's business environment to boost European investment. It therefore risks directing large amounts of money into poorly targeted interventions.

- A disciplined approach is needed to reconcile growth and security which should:

- prioritise open-economy reforms (regulatory streamlining, single-market deepening, increased skills and better functioning capital markets);

- apply a formal screening model to identify harmful dependencies, rather than treating all dependencies as strategic priorities; and

- focus on solutions that boost productivity and resilience simultaneously, including trade diversification and domestic reforms, before considering a more interventionist approach.

- Direct intervention should be used with discretion, applied selectively where there are no other effective ways to address the most important harmful dependencies.

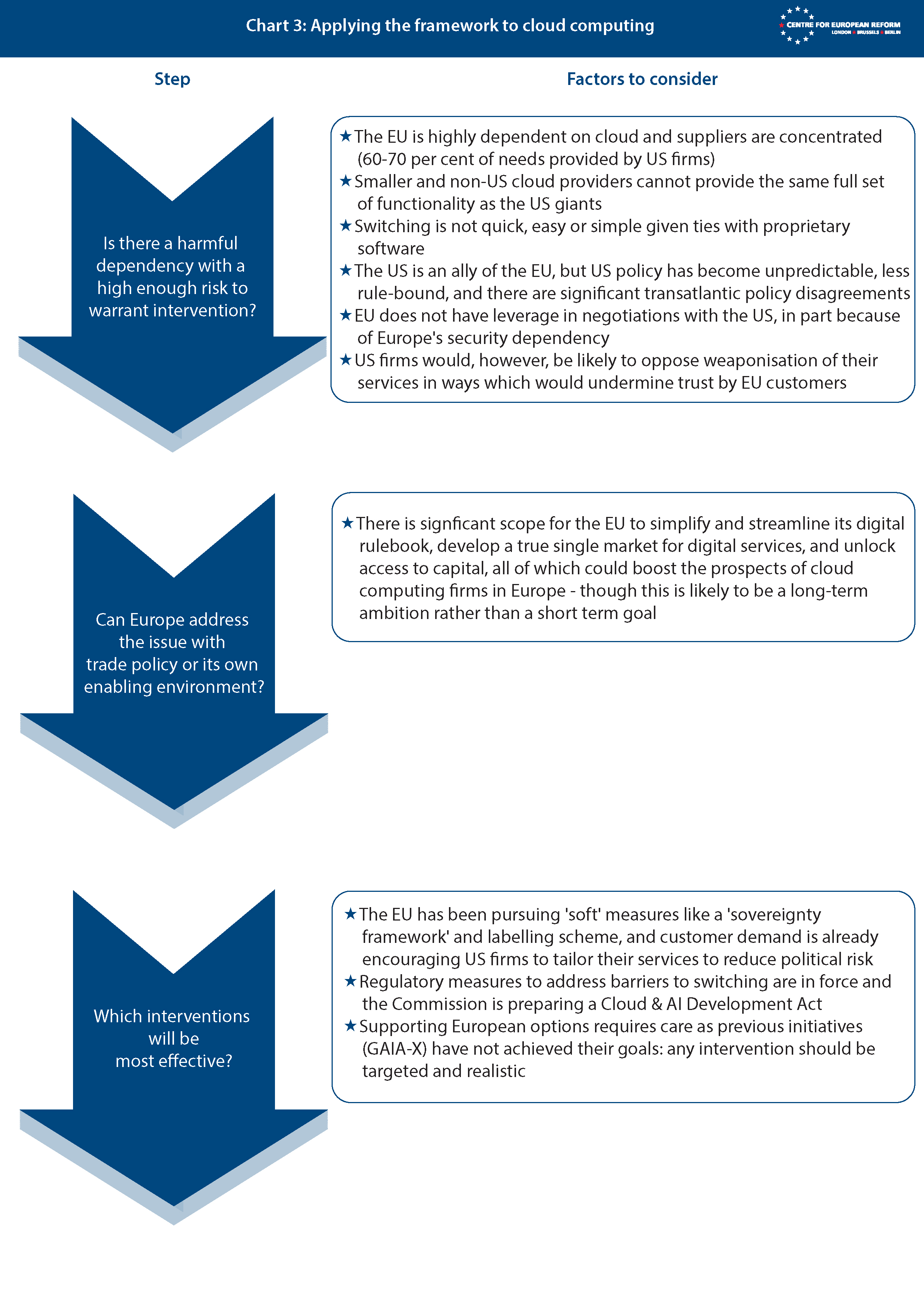

- Case studies (covering rare earths and cloud computing) show how our proposed approach could work, and show that different sectors require tailored and context-specific responses rather than a single subsidy model.

- Governance weaknesses in the current ECF proposal – insufficient transparency, unclear criteria, weak expert oversight, and risk of mission-creep – could dilute its impact and need to be addressed.

- If executed with discipline, the ECF could help ensure that economic security reinforces Europe’s productivity and innovative potential, rather than undermining it.

Europe’s trade-intensive business model faces unprecedented challenges. Through a combination of state support and a hypercompetitive internal market, China is starting to dominate globally in areas in which Europe had hoped to be an export leader – including electric vehicles and renewable energy – while Beijing continues to complicate access to its own market.1 The US, meanwhile, has raised tariffs on imports from most of the rest of the world, marking a further step away from a commitment to international trade rules. The increasing Sino-American great power rivalry is undermining the stability of the global economic order. In this difficult environment Europe has to find a way to safeguard both its prosperity and its security.

Globalisation has increased world prosperity by creating supply chains that allow for a very high degree of specialisation and efficiency, while also creating many mutual (and some more unilateral) dependencies. The new, more hostile international political climate is encouraging countries to reconsider the risks associated with all these dependencies and the overall security of their supply chains – though often without distinguishing between mutual and unilateral interdependencies. Political risk has increased, and therefore Europe must engage in more risk management, at the firm, national and European level. Much of this could come at a cost to economic efficiency or public budgets.2

Openness and market-driven innovation are the most important ways to boost competitiveness, especially since Europe has less ability to engage in a subsidy race than the US and China.

At the same time there is increased urgency about how to revive Europe’s flagging growth. Europe’s economy has disappointed since the financial crisis. In particular, Europe lags behind the US when it comes to productivity and the commercialisation of innovation in high-tech sectors, as laid out in two reports on European competitiveness last year, by Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta respectively.3 Closed markets, protectionism and a greater focus on security could make these problems even harder to solve. The US and China collectively remain important trading partners for Europe. In goods, the US absorbs 20.6 per cent and China 8.3 per cent of the EU’s exports, while they respectively comprise 13.7 per cent and 21.3 per cent of the EU’s imports. In services, the US absorbs 22.3 per cent and China 4.1 per cent of the EU’s exports, and they respectively comprise 33.5 per cent and 3.4 per cent of the EU’s imports.4

However, the vast majority of the EU’s trade is with the rest of the world. It is an economic imperative for the EU – and many of its trading partners – to maintain the global trading order and to preserve open markets. Doing so will help boost European firms’ productivity by giving European firms a wider range of inputs and more opportunities to scale their businesses globally. In doing so, firms will also be better able to diversify their supply chains and increase the dependencies of other parts of the world on European goods and services. In this way, productivity growth and economic security can mutually reinforce each other.

Openness and market-driven innovation – supported by reforms to improve Europe’s trade and its business environment – are the most important ways to boost competitiveness, especially since Europe has less ability to engage in a subsidy race than the US and China. The aim should be to maximise Europe’s opportunities, by helping European firms identify and grow in areas of specialisation where the bloc has a sustainable comparative advantage, rather than fixating on risks. Despite this, many within the EU see the use of industrial policy as a tool for competitiveness. Furthermore, the current European Commission has made it clear that security – including economic security – is its priority, and here many within the EU see industrial policy as playing an even more important role in supporting European technologies and firms in parts of the supply chain. The need for industrial policy has been echoed by Mario Draghi in recent months. Draghi insists that Europe must use “industrial policy actively – to cut dependencies and guard against state-sponsored competition” to “build the capacity to defend ourselves and withstand pressure at key chokepoints – defence, heavy industry, and the technologies that will shape the future”.5

Given Europe’s partially underdeveloped capital markets compared to the US (meaning there is less private money available for riskier and longer-term investment than in the US), and chronically low levels of private sector business investment,6 it has been clear that any industrial policy would have to also rely on public EU-level funding (reflecting differing budgetary situations at member-state level) and a range of other policy levers to support certain European firms. The main channel for addressing the need for public funding at the European level over the next EU budget cycle will be the European Competitiveness Fund (ECF).

The ECF is part of the Commission’s proposal for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) – the EU’s seven-year budget running from 2028 to 2034. The MFF includes:

- A €409 billion European Competitiveness Fund, comprising about 20 per cent of the total MFF. It aims to consolidate many different EU funds in order to boost the bloc’s position in four strategic sectors: (i) the clean transition and industrial decarbonisation; (ii) digital leadership; (iii) health, biotech, agriculture and bioeconomy; (iv) resilience and security, the defence industry and space. The ECF would nearly double EU funding in key areas.7 It includes tools such as loans, grants, equity, procurement and guarantees.

- A research and development programme (currently Horizon Europe), worth €175 billion (included in the €409 billion) remains separate. Both the Horizon Europe and the Connecting Europe Facility, which supports cross-border projects, are intended to be tightly linked to the ECF.

- National and Regional Partnership Plans totalling €865 billion to boost cohesion and agricultural and fisheries policies.

- The Global Europe programme, worth €200 billion, aiming to strengthen the EU’s position globally including by enhancing the bloc’s competitiveness and economic security.

- A range of smaller programmes including the Single Market and Customs Programme to drive completion of the EU Single Market.

The ECF proposal raises significant questions about how to effectively reconcile the bloc’s policy imperatives of boosting innovation and productivity with achieving economic security.

The ECF is, as its name implies, primarily intended to boost the bloc’s competitiveness: which suggests its role should be focused on economic growth through innovation. However, the Commission sees economic security as an inherent part of the competitiveness agenda, and hence ECF funds could be used to a large extent to address Europe’s dependencies. In the proposed ECF, the Commission builds on the Competitiveness Compass released in January and ultimately the Draghi report in identifying three key factors necessary for European competitiveness:

- closing the innovation gap;

- decarbonisation; and

- reducing excessive dependencies and improving security.8

Of these three factors only the first one is traditionally considered a key element of productivity growth. Decarbonisation and economic security on the other hand are both elements that have the potential to impose significant costs as well as benefits to economic growth. Decarbonisation is outside the scope of this paper, but economic security as an element of competitiveness presumes that geopolitical rivalries and weaponisation of dependencies will be an enduring feature of international economic relations going forward. Steps to improve economic security may be necessary to reduce the risk of future economic disruption and the ability of foreign governments to stifle European growth, but how well they deliver this goal will be difficult to judge. There is a real risk that ill-judged measures to improve economic security may impose costs without delivering any meaningful long-term gains.

Nevertheless, as member-states and MEPs are negotiating over the MFF, including the ECF proposal, the Commission’s plans have some potential to offer an improvement on the status quo: in particular by enabling a simpler, more comprehensive and more strategic approach to industrial policy which supports European interests rather than those of individual member-states. However, the ECF proposal also raises significant questions about how to effectively reconcile the bloc’s policy imperatives of boosting innovation and productivity with achieving economic security. One risk is that the ECF encourages the Commission to see intervention in markets as the primary, ‘first resort’ way of addressing economic risks, when other options like trade policy can do a more efficient job and be more consistent with productivity growth. Where more intrusive interventions are justified, their design will require extreme care – guided by technical and commercial experts and respecting the need for long term certainty.

All this will require discipline, safeguards and oversight. However, the Commission proposal would instead significantly expand its discretion over the disbursement of public funds. What is missing in the Commission’s proposal is a framework to identify:

(i) where harmful economic dependencies exist;

(ii) how Europe could improve its enabling environment and/or trade policy to address the harmful dependency; and

(iii) how to design policy initiatives to be as consistent as possible with Europe’s most significant economic achievements: the level playing-field in the single market, a robust approach to competition and its openness to global trade.

This policy brief aims to fill that gap by proposing a framework and set of safeguards to better reconcile economic growth and economic security. The report explores how we may manage these risks best, in a way which is most consistent with the need for increased competitiveness. We recommend that the most growth-enhancing ways to enhance security are to improve the enabling environment for investment in Europe and improve its trading links with the rest of the world. Where these are not sufficient, we suggest the most efficient and targeted ways to use the ECF to help correct harmful dependencies.

Background and context

The EU’s trade-driven growth model is being questioned

For decades, EU growth has been supported to an increasing degree by growth in exports, fuelled by a business-friendly environment in the EU and growing global trade liberalisation.9 But as both the US and China partially close their markets and competition intensifies, export-led growth will be more challenging than in the past. Europe will therefore have to boost its own growth by improving its productivity. It can do this by increasing the effective adoption and diffusion of existing technologies. It can also carve out technological leadership in the areas in which it has an enduring comparative advantage. However, in both adoption and tech leadership, the EU is slipping behind the US and China.10

Europe will therefore have to boost growth through effective adoption and diffusion of existing technologies to increase productivity.

The US has benefited from dynamic markets which lead to strong technology diffusion and adoption, and a financial ecosystem and culture that supports risk-taking while enabling successful innovators to scale up rapidly. This has allowed US companies to dominate the digital economy, whether it comes to cloud computing, social media, search engines, operating systems or AI – all areas where European companies only have a marginal presence. China, on the other hand, is matching, and sometimes surpassing, European technology in areas where Europe traditionally has had strengths such as vehicle production, machine tools and clean tech.11 Rather than ‘picking winners’ – which did not play a definitive role in the success of America’s tech giants – the EU needs to reduce barriers to innovation, and improve competitive dynamics by building out the single market so that firms which successfully harness innovations can more easily scale and dislodge less innovative firms.

All this takes place in a context where the EU is also facing a less friendly external environment more broadly. The relationship with Russia is now openly hostile after the invasion of Ukraine, cutting off a source of cheap fossil energy. The US, while still Europe’s most important ally and trade partner, has turned increasingly away from the rules-based order and towards protectionism. China has created an economic model where companies benefit from substantial state support – significantly more than in OECD countries.12 For example, research covering firms in 13 sectors showed Chinese state support amounted to 4.5 per cent of the revenues of Chinese firms against 0.69 per cent in OECD countries. This support fuels export-led growth that is increasingly putting European production under pressure. There are a number of sectors, such as solar panels, batteries and rare earths where Europe is now dependent on China, as the recent experience with rare earth export restrictions shows.13 And in digital technologies like cloud computing, increasingly relied on by European firms across all sectors, the EU is largely dependent on the US. Although both China and the US to some extent are constrained by their respective dependency on the EU as their largest export market, China has the ability and willingness to use strategic dependencies as tools of state power; and fears are growing that the US would be prepared to weaponise the EU’s dependencies on US digital technology.

The fundamentals of the EU’s growth model still need to be nurtured

Nevertheless, the EU remains strongly reliant on third countries for trade. More than 70 per cent of Europe’s goods and services exports and more than 60 per cent of its goods and services imports are from other parts of the world than the US and China. And productivity growth – particularly given Europe’s lack of critical raw inputs – is likely to rely on using technologies and inputs that, for now at least, are not predominantly European. Trade is, generally, a mutually beneficial phenomenon and mutual dependency will therefore, more often than not, also be mutually beneficial. There is still substantial growth potential in increasing trade with growth markets elsewhere in the world, such as the Indo-Pacific region and South America. Raising barriers for inputs could endanger the competitiveness of European exports that rely on those very inputs, by increasing costs and reducing productivity.

The EU should not fall into the temptation of trying to replace every harmful dependency with purely domestic supply.

This creates a dilemma for EU policy-makers: how to combine productivity growth, which requires open markets for inputs and market access for EU exports, with greater economic security.

The extent of this dilemma can be overstated. The fundamentals of the EU’s model for economic growth can also support economic security. For example, productivity growth, market leadership and reducing dependencies all benefit from the EU building on its extensive network of free trade agreements, to help European firms diversify their supply chains, grow their exports, and scale up globally. This ensures Europe can benefit from innovation and productivity growth in the rest of the world.

Other strong framework conditions have also helped to promote competition and investment, encouraging firms to strengthen their resilience. For example, the single market has lowered barriers to trade within Europe: helping strengthen competition and ensuring successful firms can scale quickly. This, in turn, can help ensure that European firms are successful in global markets so that where the EU has dependencies, these are mutual and not one-sided or even one-sided in the EU’s favour – which would be the case if the European firms produce vital technologies that others lack.

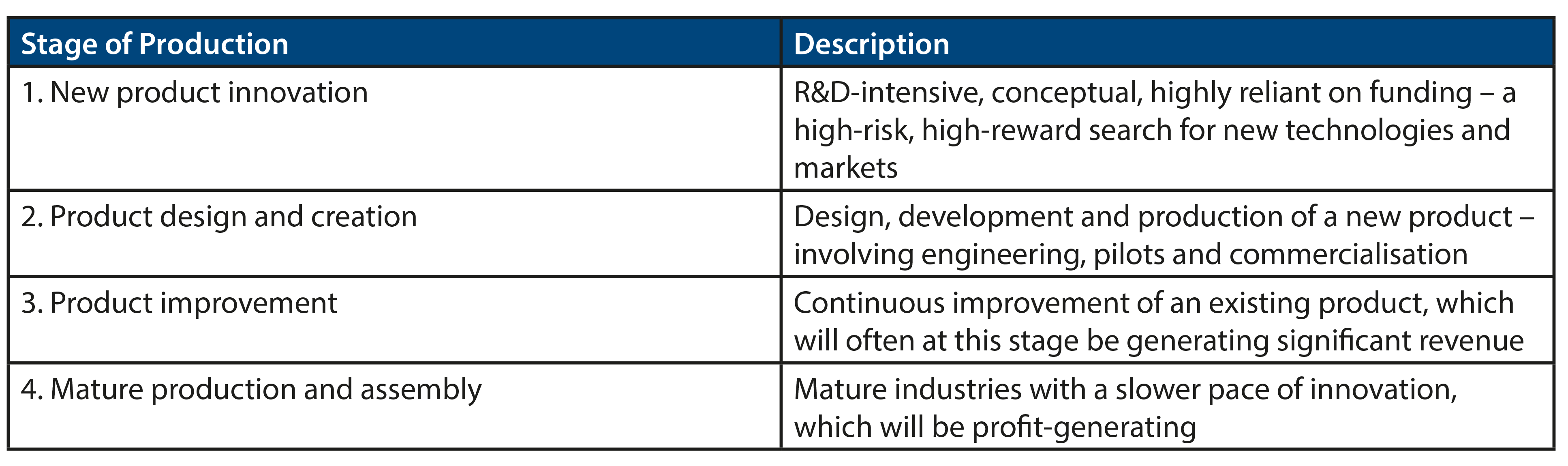

This would enable a strategy for targeted intervention to focus – to the greatest extent possible – on supporting, where an economic sector requires that support, the specific phase or stage in that economic activity that the private sector cannot adequately fund alone. In designing industrial policy, it can be useful to conceive of four different stages of production a sector or product may find itself in:14

The EU already provides extensive support at the earliest stage when R&D support is required and, in stage three and four, private funding ought to be sufficient if a firm actually does have the prospect of becoming viable and succeeding on its own merits. The second stage should in most cases be the focus of the ECF given the long time-horizons, very early-stage technology, high-risk high-return cases or positive externalities which may not always captured by the market. This may, in certain cases, justify a focus on certain parts of the commercialisation process in sectors like cleantech, health research and early-stage tech such as quantum computing. By filling in the gap created by reduced research funding in the US, the EU can build on its own research capabilities.

However, in certain cases support for products in stage three and four may be justified on economic security grounds. This may be the case when the products form a harmful dependency dominated by a single supplier or country that makes continued reliance inadvisable due to instability of supply and/or fear of weaponisation. However, this is unlikely to be a growth-enhancing form of investment unless there is a significant risk that the dependency would be weaponised. To avoid a slippery slope towards protectionism and wasteful support for mature industries it would therefore be necessary to carefully define both the concept of harmful dependency and define criteria for intervention that limit the cost and target the projects that are most necessary.

The EU should also not fall into the temptation of trying to replace every harmful dependency with purely domestic supply. As an open economy, the most cost-effective way to diversify supply will often be to find alternative suppliers in friendly countries. Europe may lack either the natural resources or the enabling environment because of labour costs, high levels of regulation or other competitive disadvantages such as high energy costs.

The goal would be to ensure that, in the few areas where public funding or other forms of proactive intervention in markets is justified, the measures taken to achieve this are targeted. They should be designed in ways which represent a sensible balancing of cost and benefit – and which enable public resources to be allocated primarily to growth-enhancing activities, and to the specific phases of those activities where the market will not deliver what is needed. To the extent possible, the measures should be designed to crowd in private capital and not replace it.

Interventions meant to promote the EU’s strengths can, if poorly designed, involve market distortions and carry risks of industry capture and supporting unviable solutions.

Defensively protecting against harmful dependencies is not the only option. The EU must supplement this defensive approach with a more offensive and growth-enhancing strategy to boost the EU’s strengths, and thus increase EU trading partners’ dependency on the EU. In addition to boosting the bloc’s competitiveness, and thus its economic heft in the world generally, building out from the EU’s export strengths could often provide an important counterbalance to the EU’s dependency on other countries. Possible interventions to promote the EU’s strengths can, if poorly designed, involve market distortions and carry risks of industry capture and artificially supporting otherwise unviable solutions. However, a well-designed offensive strategy can unlock investment in areas where current market conditions lead to harmful dependencies.

The ECF

Nevertheless, many policy-makers are concerned that – even if open markets can help secure Europe stronger market presence in the long run – in the short run, open markets may increase some of the EU’s dependencies. Policy-makers are therefore increasingly looking at measures like ‘buy European’ mandates and public subsidies to address this problem. These represent a potentially significant shift away from the EU’s traditional approach of ensuring a level playing field, strong competition, and open markets.

The most recent development in this direction is the European Commission’s proposal for the ECF, which envisages significantly increasing public subsidies at the EU level, shifting procurement practices and simplifying the process of allocating recipients of EU funding, while also giving the Commission significantly more freedom to decide where and how to provide subsidies. While the ECF has as one of its objectives to improve “competitiveness”, the ECF also takes a two-pronged approach, focusing not just on boosting Europe’s market leadership but also on risk mitigation:

“To ensure its autonomy in the global economy, the Union should guarantee its technological and industrial leadership in strategic sectors, starting with critical raw materials supply chains, to develop and manufacture strategic technologies in Europe, as well as mitigate risks affecting its security and resilience emanating from critical external dependencies.”

Building a more resilient and self-sufficient EU to address economic security risks therefore remains one of the most important objectives of the ECF – and one which the Commission envisages the EU “guaranteeing”, without much reference to the role of the individual firms and national policies to achieve this.15 The role of economic security is reinforced under various policy windows: the objective of boosting digital leadership, for example, includes “achieving technological sovereignty by building resilient digital ecosystems”.16

The ECF consolidates 14 different existing programmes such as InvestEU, the Digital Europe Programme, the Connecting Europe Facility, and the European Space Programme (and improves coordination with two larger remaining programmes, Horizon Europe and the Innovation Fund). Rather than the narrow focuses of each of these programmes (many of which have separate sub-pots allocated to particular purposes), the ECF focuses on four “policy windows”. Each of these has its own “indicative financial envelope for the programme” (though up to 20 per cent of the envelopes can be reallocated), as follows:

- Clean Transition and Industrial Decarbonisation – €26.21 billion;

- Health, Biotechnology, Agriculture and Bioeconomy – €20.4 billion;

- Digital Leadership – €51.5 billion;

- Resilience and Security, Defence Industry and Space – €125.2 billion.

€11 billion is allocated for general competitiveness such as cross-cutting activities. The funding is not necessarily provided only by grants. For example, the ECF envisages some allocations being made by way of guarantees aimed at attracting private investment, and the ECF also envisages public procurement as an important part of the toolbox.

The ECF is therefore not a single fund but a flexible architecture of instruments – grants, equity, loans, guarantees, and blended finance – that can be tailored to different market failures and economic contexts. To maximise the impact of the ECF, it is essential that the right instrument is used, depending on the type of project and what stage it is at, as each mechanism is best suited for addressing different risk and capital needs.

To maximise the impact of the ECF, it is essential that the right instrument is used, depending on the type of project and what stage it is at.

Grants are a straightforward form of intervention with a long history in the EU. They are best used when market failures are clear, spill-overs are large and uncertain, or when policy objectives have a public-good character. These cases could include:

- De-risking frontier innovation, such as carbon-capture, hydrogen, and next-generation batteries;

- Compensating for co-ordination failures in sectors with high up-front costs but uncertain returns; and

- Improving cohesion across member-states, by supporting less developed regions in catching economically and socially.

Grants should be one-off instruments. They are therefore best suited to early-stage, high-risk projects with limited commercial prospects or primarily public-good objectives where a one-off influx of capital has a good chance of delivering that public good. Grants can help absorb initial risks and fill funding gaps where private capital is absent. Their effectiveness depends on timing (early-stage vs deployment), targeting (avoiding subsidy duplication), and additionality (ensuring they only support projects would not have been implemented without the support).

Equity or quasi-equity instruments – delivered mainly through the InvestEU programme, the European Investment Fund (EIF), could help compensate for Europe’s shortage of risk capital for scale-ups and cutting edge tech ventures. They also allow for public participation in potential profits and ensures European ownership – and would allow returns to be recycled into new projects. However, there are also considerable losses to be made when investing in equity in start-ups. This means that this kind of support is occasionally bound to lead to financial losses for EU taxpayers.

The main challenge of such instruments lies in governance: ensuring the EU’s role as investor does not politicise firm-level decisions or distort competition, for example by encouraging the EU to continue to plough money into a firm rather than quickly admit if a project has failed, in the process pushing out potentially more successful firms.

For more mature innovations, loans offer cost-effective financing for scaling and deployment, supporting projects with plausible revenue streams and technologies. Loans are particularly suited for capital-intensive deployment projects – such as renewable energy installations, grid modernisation, or manufacturing plants – where revenue streams are relatively predictable once initial risks are mitigated. However, loans are less suitable for early-stage innovation or uncertain technologies, where the risk of non-repayment is high. In those cases, guarantees or grants could provide better options.

Guarantees provide a risk-sharing model where the EU would absorb part of the downside risk faced by private lenders. This approach multiplies the effect of limited public funds by leveraging private balance sheets. Guarantees can be particularly useful in markets suffering from co-ordination failure or information asymmetry. By providing first-loss coverage or partial risk sharing, guarantees enable commercial banks and institutional investors to finance projects that would otherwise be deemed too risky. They also help reduce distortions by relying on co-investment rather than outright subsidy. But they also depend on private-sector uptake and credit-risk assessment to succeed.

Finally, blended finance instruments combine public and private resources to support transformative projects with partial market viability – using grants to cover non-commercial elements while repayable finance supports commercially sustainable components. It helps mobilise private investment for public-policy objectives by strategically combining limited public resources with market capital. By leveraging private balance sheets, blended finance can increase the impact of scarce public funds. It requires transparent governance to ensure that private participation delivers genuine additionality.

In a globalised economy dependencies are widespread and governments can find it difficult to tightly define a ‘fence’ around those dependencies which are most harmful.

Much academic research illustrates that, while industrial policy can sometimes produce successes, it has significant risks too.17 To be successful, interventions need to be carefully targeted and part of a coherent overall and long-term strategy, and there must be important institutional safeguards to avoid industry capture. The risk of a predetermined amount of funding to be allocated for ‘sovereignty’ purposes is that the European Commission begins to see the Fund as ‘money to be spent’ rather than taking a carefully calibrated approach, which does not assume subsidy or procurement preferences are always the right answer. This paper proposes a toolkit to help encourage this discipline.

Our starting point is that competitiveness does not necessarily require large amounts of public subsidy, but that in the absence of meaningful action to unlock private capital, it may provide some benefit in some cases if used judiciously. However, the EU must avoid entering into a subsidy race with the US and China, particularly given their greater ability to mobilise capital, and their willingness in some sectors to do ‘whatever it takes’ to secure a lead. Given the fact that EU does not have (and in some cases should not emulate) these features, an approach focused on ‘keeping up’ is doomed to fail: even if it was economically viable, it is politically implausible that the EU could subsidise or protect all strategic sectors to the extent of its geopolitical rivals. This means the EU must leverage as far as possible its comparative advantages and tools like trade policy to boost security – keeping subsidy only to where it is essential.

A more targeted approach should be aimed largely at addressing areas where markets do not always work optimally. While part of this approach could aim to reduce foreign dependencies, steps which might undermine the EU’s efforts to boost its competitiveness need to be tightly constrained. For example, it will be important to distinguish harmful strategic dependencies from innocuous ones. In a globalised economy, with value chains spanning across multiple borders, dependencies are widespread and governments can find it difficult to tightly define a ‘fence’ around those dependencies which are most harmful. For example, while the last US administration sought to limit trade with China by establishing a “small yard with a high fence”, over time that small yard grew progressively larger.18 The desire to reduce harmful dependencies, if these are not clearly defined and the consequences of limiting trade fully thought through, can therefore easily shift into widespread protectionism. That is profoundly damaging to economic growth, particularly for a trade-intensive economy like the EU.

A toolkit for reconciling growth and security

The EU is a global trade powerhouse. Now that the US is engaging in increased protectionism and more volatile policy, the EU will in comparison have an advantage by retaining its open, rules-based, relatively predictable and consistent policy approach. It should build on that advantage by refraining from making trade policy subservient to industrial policy, as hinted at in the Draghi report.

Since state intervention has a cost – and ECF funds which are used to address dependencies will not be available for more growth-enhancing purposes – it should similarly be limited and targeted, to fill gaps that the private sector cannot fill. To prevent a slide into protectionism or excessive state intervention, we propose in this section a toolkit to identify harmful dependencies and then to determine the right type of policy intervention to mitigate those dependencies. To protect European competitiveness from harmful dependencies an expansion of the ECF toolkit is required. This would enable the EU to design more effective interventions at minimal cost to EU taxpayers. Then alternative options can be considered, that do not require public outlays and support trade diversification rather than only on-shoring and local production can be canvassed. In other cases, we propose a refinement of how the ECF tools can be used to ensure public funding is used in the most effective way.

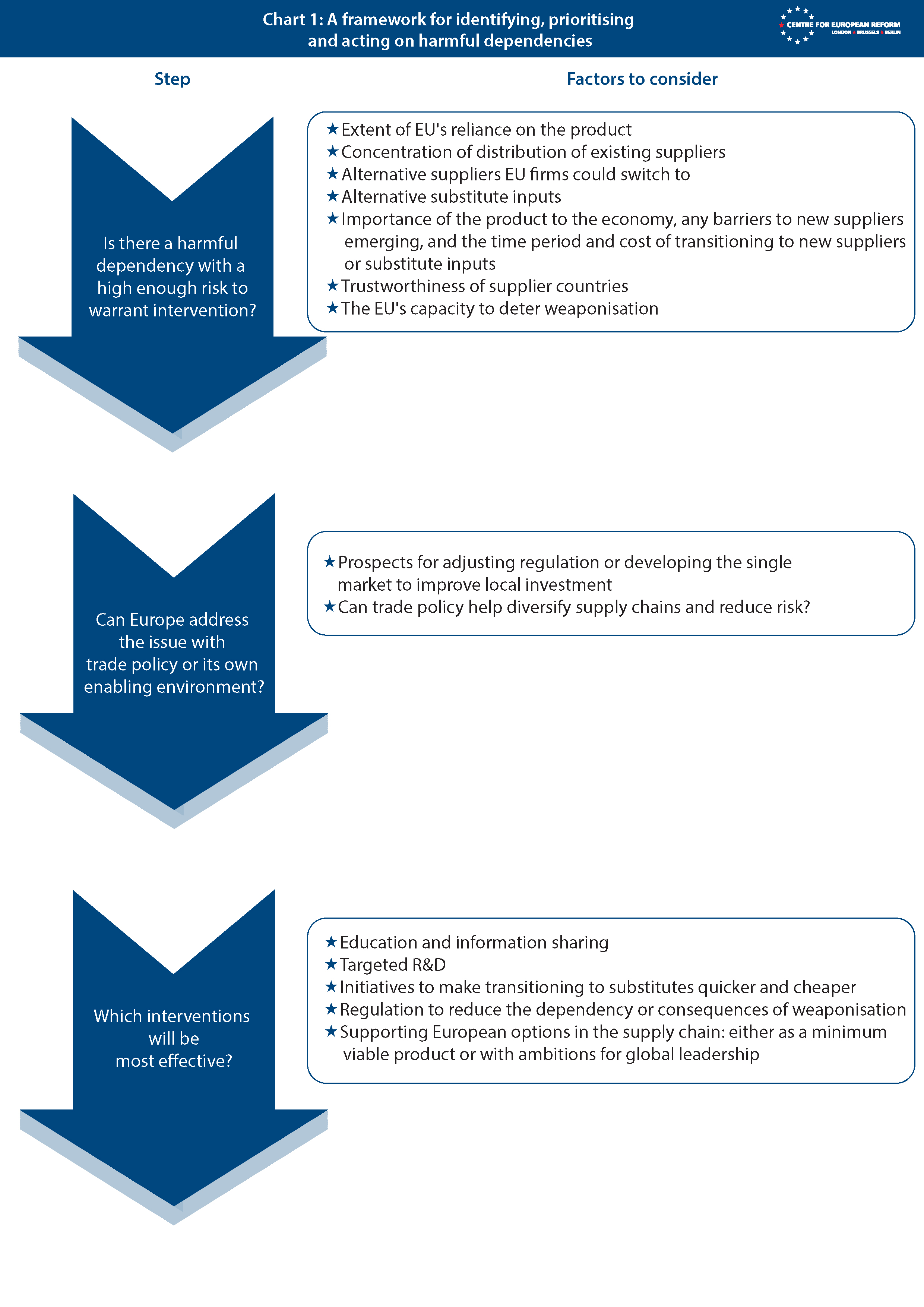

Step 1: Which dependencies are harmful?

The ECF refers repeatedly to the concept of “critical” dependencies and often implies that they must all be addressed. For example, the ECF states that:

“While Europe’s digital transformation is accelerating, the many critical dependencies on non-Union suppliers (from raw materials, advanced semiconductors, and AI chips to systems, infrastructures and services) require European alternatives.”

In other places, the ECF suggests it is “strategic” dependencies that need to be addressed:

“The ever-evolving geopolitical situation underlines the need for Europe to ensure its own strategic autonomy and avoid strategic dependencies.”19

A careful and nuanced approach to identifying which dependencies to tackle is essential.

In yet other places, the ECF simply suggests that all dependencies need to be reduced (“To ensure its resilience, the ECF should support actions aimed to reduce dependencies and diversify supply in strategic sectors”) or that the goal should be “strategic independence”.

The lack of clarity within the ECF proposal about the types of dependencies that the ECF will address is concerning – but the formulations all reflect a growing view that the EU’s dependencies which need attention are large in number and broad in scope. For example, as part of the EU’s Economic Security Strategy, the European Commission produced a list of 10 broad technological sectors where it considered dependencies should be reduced – such as advanced semiconductors, AI, quantum, biotech, digital technologies, sensors, space, energy, robotics, and advanced materials.20 The Commission announced in 2023 that it was carrying out risk assessments in four high-tech areas,21 but these analyses have apparently not been published (and may not even be complete), highlighting that the process of identifying risks is far from trivial. Surprisingly, in a number of the 10 sectors mentioned in the Economic Security Strategy, Europe is already in the technological vanguard and has market leadership, such as in parts of the fossil-free energy sector, sensors and robotics. This implies that the EU’s current trade strategy is working well at giving European researchers and firms the inputs they need to innovate. Indeed, some of these sectors, far from making Europe weak or vulnerable, give the EU export strengths which could help neutralise the risks of also having dependencies.

As a trade-intensive economy, which focuses on adding value in supply chains where it has comparative advantages, it is self-evident that Europe will have many dependencies, including in so-called strategic sectors. This does not mean that all of them are a problem. Even if they were, prioritisation would be needed because they could not all feasibly be addressed – and trying to target every area of dependency in the ECF’s policy windows would probably lead to an attempt to do too much at once. In the digital sector, for example, providing European options at each point in the value chain where Europe has strategic dependencies has been estimated (even by proponents of such as strategy) to cost €300 billion – far more than the €51.5 billion assigned to digital leadership under the ECF.

Instead, a more careful and nuanced approach to identifying which dependencies to tackle – which we call “harmful dependencies” – is essential.

The first step is to determine whether a harmful dependency exists at all. This should take into account the following factors:

- The extent to which the EU relies on an import for a particular product or service. If a significant proportion of demand for an input is being met by domestic EU production, then there is no import dependency.

- If there is a dependency on an import, the distribution of suppliers. If the EU’s supply is heavily diversified across firms from different countries, then it is unlikely any import dependency poses significant risk.

- The alternative suppliers that EU customers could switch to. This would include an assessment of global trade in the input. For example, EU customers may purchase from a single supplier, or suppliers only in a single country, because of cost considerations rather than the lack of alternatives. In such cases, EU customers could obtain the same suppliers elsewhere, albeit at higher cost. If the cost is just marginally higher, it would function as a tax, but a high cost difference could be prohibitive.

- The alternative inputs that EU firms could switch to and the barriers to making such a switch. For example, when the EU chose to significantly reduce pipeline gas from Russia, the continent was able to rely more heavily on stockpiling and LNG imports instead, although this required some significant short-term investment in regasification facilities.

Where a potentially risky dependency exists, the next step is to evaluate the level of risk and therefore whether it warrants intervention.

This analysis needs to take place for each input rather than for each product or service: a product or service may rely on many inputs, and reliable access to all of them may be essential. It is difficult to apply a specific threshold or a hard-and-fast rule about the extent to which reliance on imports, or lack of diversification of suppliers, might deserve further scrutiny. Indeed, in the event of a crisis, a critical import dependency can emerge suddenly and unexpectedly, such as the dependency on imported personal protection equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. In determining the level of imports, and the level of concentration of suppliers that is tolerable, policy-makers should take account of a range of factors including:

- The extent to which the European economy currently relies on the dependency, and the immediate and direct consequences if access were to be restricted.

- The nature and significance of any barriers to new alternative suppliers emerging, either in Europe or elsewhere. This would require an assessment of whether a dependency is physical/geographical (for example, where there is reliance on a critical raw material that is not widely available); a question of policy choices which could change (for example, many rare earths are available in Western countries, albeit that currently environmental policies mean mining such materials does not take place); or simply a question of competitiveness and investment (in other words, new suppliers could emerge in new countries if existing suppliers ceased exports, but they have not done so already because they are not currently cost-competitive).

- How quickly and how costly any required transition to new suppliers would be. As an example, Europe was able to reduce dependency on Russian gas quickly, although the cost of doing so (including, as mentioned above, through regasification investments) was significant. Rare earths would be much cheaper to replace, since they are not expensive relative to the quantities needed in European industries, but would probably take a much longer time, depending on the exact products and their position in EU value chains.

Importantly, only the first step in this process can rely on a ‘static’ assessment: looking at how markets operate today. The remainder of the steps demand a dynamic assessment, recognising how supply chains change and adapt in relation to fluctuations in supply and demand. For example, the drastic reduction in trade with Russia as a result of sanctions following the country’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine proved that free markets are often more adaptable and innovative than many economists and market observers expect: initial estimates that a sudden ban on Russian gas would cause €429 billion in lost output for Germany annually proved well off the mark.22 Of 50 ‘critical dependencies’ on Russia, the EU has managed fairly well without any of them – often thanks to changes in investment patters and policy changes. In the end, the dependency on gas is the only one that proved to have a critical impact on the overall economy, given the high cost of the energy crisis.

If the above assessment nevertheless identifies that a potentially harmful dependency exists, the next step is to evaluate the level of risk and therefore whether it warrants intervention. This is an assessment which inevitably involves subjective considerations about geopolitical risk. Nevertheless, to impose rigour at this stage of the assessment, policy-makers should consider the following factors:

- The EU’s level of trust in its supplier countries. Policy-makers must take into account factors such as whether the country is governed under the rule of law, the country’s history of legal and policy predictability and consistency, and the degree of similarity in values and geopolitical goals of the supplier country. Dependence on Norway, the UK or Japan is, for instance, very different from dependence on Russia or China.

- If weaponisation of a dependency from that country is a real risk, how the EU could deter such weaponisation. This will require a holistic assessment of the EU’s overall trading relationship with the country and the areas in which the EU has leverage over its trading partner. Importantly, this might include the importance of the EU as an export destination for the country – not just whether the EU has its own exports it can withhold to retaliate. If the EU has a politically viable path to ‘striking back’ if its dependency on a country was weaponised, this may make the dependency less problematic.

The purpose of this initial ‘screening’ exercise would be to enable the EU to prioritise properly. As noted above, existing exercises to identify the EU’s dependencies have often created lists which are so broad that it would be implausible for the EU to address them all – and which would imply extensive interference across broad swathes of the European economy, with potentially very significant impacts on efficiency and economic growth. If too many products are classified as strategic priorities, then in practice there are no priorities at all.

What is needed is for the EU to identify and prioritise: identifying only the dependencies which are actually harmful. This would free up trade policy and public resources to focus on enhancing the EU’s strengths in areas where it has a comparative advantage. Such an approach would both be growth-enhancing and would enhance the EU’s position as a global exporter, increasing other countries’ dependence on the EU.

Step 2: How could Europe improve its enabling environment and/or trade policy to address the harmful dependencies?

Having identified areas where the EU has genuinely harmful dependencies to prioritise, the second question which EU policy-makers implementing the ECF should address is whether a combination of changes to the framework environment in Europe and/or trade diversification could be sufficient to mitigate these risks.

It is easy to foresee situations where a harmful dependency is simply the result of Europe’s enabling environment being insufficiently supportive of investment.

The ECF has references to supporting the enabling environment for investment in Europe – for example, the ECF’s objectives include improving firms’ access to finance, reducing reporting burdens, boosting access to skills, and increasing integration of the single market.23 However, none of these are referenced in relation to supporting resilience and economic security; they are seen only as options to boost competitiveness generally.

This is an oversight because it is easy to foresee situations where a harmful dependency is simply the result of Europe’s enabling environment being insufficiently supportive of the emergence of local alternatives. In such situations, the problem would lie not with trade dependencies but with Europe’s internal regulatory environment or with market integration. For example, the Commission should consider:

- Whether regulations might impose such burdens on businesses that they choose not to invest and grow in Europe, leading the bloc to become reliant on imports in a way which has a negative impact on its economic security (and whether changing those burdens is realistic or desirable, particularly when they reflect other important interests such as protection of the environment); and/or

- Whether the lack of a single market is a factor preventing would-be European firms from achieving the scale they would need to be viable competitors.

There has been a wealth of material in recent years highlighting how complex, sometimes ill-designed, regulation and the lack of political attention paid to the single market has constrained investment.24 The International Monetary Fund estimates that if internal barriers to trade in the EU were at the same level of those in the US, then labour productivity could increase by 7 per cent over seven years;25 while at the same time, it could enable growth of economic activities in which the EU is currently excessively reliant on others. The Commission’s Economic Security Strategy acknowledges the importance of developing the single market as a way to boost the bloc’s resilience and to develop leverage to keep global supply chains open.26 The single market can significantly boost economic security by helping improve the business case for new investments in Europe – yet its role has been chronically underemphasised.

If the Commission identifies regulation or deficiencies in the single market as potential barriers to economic security, they ought to be addressed as a matter of urgency before concluding that more intrusive market intervention is needed.

In some cases, the Commission will be able to progress initiatives to tackle these barriers to security directly – for example, by proposing new regulations to simplify, streamline or harmonise the regulatory environment in Europe; or in other cases amending regulatory standards to enable investments which would previously have been disallowed or allowed only with unworkably high costs (such as environmental mitigations). In other cases, responsibility may lie with member-states.

EU trade policy should aim to conclude strategic partnerships on a reciprocal basis with friendly countries as an add-on to EU FTAs.

The Commission’s proposal for the 2028-34 budget envisages creating National and Regional Partnership Plans.27 These will be tailored to each EU members’ needs and funding will be conditional on member-states delivering policy reforms essential to boost competitiveness.28 This approach learns from the post-Covid Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) and offers the potential to provide more impetus for member-states to deliver national reforms. This will need to be coupled, however, with a significant increase in transparency, performance metrics and clear monitoring of progress compared to the RRF approach.29

Many products, such as fossil energy and certain rare earths, either do not exist in sufficient quantity on European territory or would not be feasible to produce given labour and environmental costs. For other products, other countries, whether the US or in Asia, have a technological lead in innovation or production that would be difficult to surmount. Where that is the case, there would have to be a very compelling case for state intervention in order to try to ‘catch up’. The fundamental driver of globalisation is productivity growth through specialisation, and no single trade bloc can be a leader across all domains.

This means that improving the enabling environment in the EU will not always be sufficient. To its credit, the ECF does refer to the role of trade policy in addressing harmful dependencies. For example, the ECF has a general objective of “reducing or preventing the Union’s strategic dependencies, and reinforcing the Union’s resilience, and economic security, including through diversifying sources and markets”.30 However, the ECF provides little guidance on the relative importance of diversifying the EU’s trade as compared to other more intrusive tools like subsidies.

The EU has an extensive number of free trade agreements, which cover 74 per cent of its trade in goods with partners other than the US and China.31 These agreements focus on market liberalisation, which has provided considerable benefits to European companies. However, while these agreements play an important role in opening up markets, many are not especially deep,32 and they are not aimed at building privileged relationships with trusted actors. To reduce harmful dependencies through trade policy, there must also be greater differentiation and prioritisation of trade partners.

This cannot be done through tariffs that impose significant costs on importers – an approach which would undoubtedly reduce the competitiveness of the European economy. However, opportunistic and targeted agreements to improve the bloc’s access to critical inputs where those supplies are currently subjected to harmful dependencies could make a positive difference. One approach would be to ensure projects funded by the ECF are not constrained to use exclusively European supply chains where friendly countries have a strong competitive advantage, either due to technological leadership or resource availability. EU trade policy should aim to conclude strategic partnerships on a reciprocal basis with friendly countries as an add-on to EU FTAs to build trusted supply chains for strategic products. This could potentially follow the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) model, a programme of large-scale defence loans for projects which are allowed to include participation by certain trusted non-EU countries.

Step 3: If other reforms are insufficient, how could a more interventionist approach be designed?

Third, in cases where there are good and evidence-based reasons to conclude that improving the EU business environment or trade diversification would not themselves sufficiently address a harmful dependency, then the least harmful possible interventions should be identified. When this stage is reached the Commission will probably take a defensive approach aimed at addressing a harmful dependency. But it will be important to ensure that these types of interventions should not use up the bulk of the ECF – which ought to be, as its name implies, targeted primarily at growth-enhancing investments.

Defensive interventions should not use up the bulk of the ECF – which ought to be targeted primarily at growth-enhancing investments.

Here, the Commission ought to develop a ‘ladder’ of possible interventions, which preserve as many as possible of the benefits of open markets. Options might include:

- As a ‘first resort’, taking an approach focused on education and information sharing. This could include promoting greater awareness of political risk among EU customers, so that they can take this into account when making sourcing decisions. This option may not always be effective – for example, there is a risk that the market as a whole undervalues economic security risks, or that there is a collective action problem whereby no EU customer is prepared to accept a cost disadvantage by diversifying their supplies away from the lowest-cost provider. However, as this option is relatively low cost and involves no direct distortion in markets, it is an option which ought to be tried before active intervention. For example, in the case of cloud computing services, some global technology firms have proactively offered ‘sovereign cloud’ options which provide a degree of protection against policy decisions by foreign governments which could harm European customers. These ‘sovereign cloud’ solutions – while they might not always provide a complete solution to digital sovereignty concerns – do substantively mitigate some risks. Importantly, they have emerged largely in response to customer demand and policy pressure, rather than through hard-edged interventions. Similarly, some European public sector and private organisations have actively chosen to use open-source digital software in order to mitigate the risks of lock-in and service disruption.

- Investing in R&D to expand the potential alternatives that European firms could rely on. This type of measure proactively addresses dependency problems, while also potentially positioning Europe as a technology leader, particularly in cases where the new alternative could be economically more attractive than the current input (even in the absence of economic security considerations). However, its applicability will depend on the particular sector and the existence of technologies that could plausibly be developed in the near-term to avoid relying on a particular input.

- Pursuing initiatives to ease the speed and lower the cost of transitioning to an alternative input if this were ever needed. This might include, for example, initiatives to promote standardisation and interoperability of digital services, or funding pre-emptive investments to enable the use of alternative supplies. For example, Europe could have invested earlier in regasification facilities or pipelines from other sources of gas, or it could have invested earlier in stockpiling, all of which would have significantly reduced the disruption caused by EU sanctions on Russian energy. However, as these investments come at a cost, it is essential their costs and benefits are rigorously assessed.

- Regulating in order to reduce the dependency or the consequences of a dependency being weaponised. For example, the EU is actively pursuing policies to enforce the use of open standards and interoperability between different cloud computing services. Enforcing interoperability is not costless, particularly because it imposes a degree of standardisation on markets where suppliers may be innovating by providing different types of services and functions. However, in cases where the benefits outweigh the costs, these types of regulatory solutions may help EU customers avoid being ‘locked in’ to one supplier, and ensure they could switch if this became necessary.

- As a last resort, providing support to ensure there are European options in key parts of the supply chain. Even where this emerges as the best option, there will also need to be decisions about whether the European option should be a ‘minimum viable product’ or whether it is funded with goals of becoming a ‘European champion’. A ‘European champion’ could be more growth-enhancing, but only where the right conditions exist. In a couple of cases there could be a case for developing European champions, as happened with Airbus. That was a special case, however where European industrial policy created competition where there would otherwise be a monopoly, and which built off Europe’s prowess in high-end manufacturing. It is not clear how easily this analogy will translate to other sectors, particularly in cases where the primary impetus for intervention is to minimise a dependency rather than to exploit a competitive advantage. The resources required to build a ‘European champion’ may also be significant – and it might well require more significant funding across a greater set of phases of economic activity. If the EU does not have a pathway to becoming a globally competitive provider of a good or service, then its approach should be to create a ‘minimum viable product’: delivering only what is essential to address the harmful dependency, but no more than that. That may require ongoing subsidy (whether through direct grants as operating support or ‘buy European’ rules that give it an artificial advantage in competing for parts of the market). Since this will inevitably be market-distorting, it will be essential to avoid ‘mission creep’ and clearly define precisely which activities require support.

- In choosing projects to support, it will be necessary to have an open and competitive process using transparent merit-based criteria that reward excellence. This would require evaluating three questions.

- Can the project deliver increased productivity, innovation or economic security?

- Can the project achieve its goal in a cost-effective manner?

- Does the project have a reasonable chance of success?

The ECF should have a higher risk appetite than private-sector funding, but it must also consider if the project has access to the required human capital, infrastructure and material inputs. Another consideration is the competitive landscape – a very large gap to global leaders entails increased risk and would require a very important economic security rationale.

Case studies

Two sectors that have recently, for different reasons, been the focus of discussion in Europe as examples of risky dependencies are rare earth elements (REEs) and cloud computing, where Europe relies on suppliers from China and the US, respectively. Those two sectors can also serve as practical examples to illustrate how this framework might be applied.

Case Study 1: Rare Earth Elements

REE are a collection of 17 different elements that exist in the earth’s crust in small, dispersed quantities and are critical inputs in key technologies such as high-strength magnets used in wind turbines, motors, batteries and fuel cells. The REE industry is a mature, stage-4 established industry with decades of production and technological development.

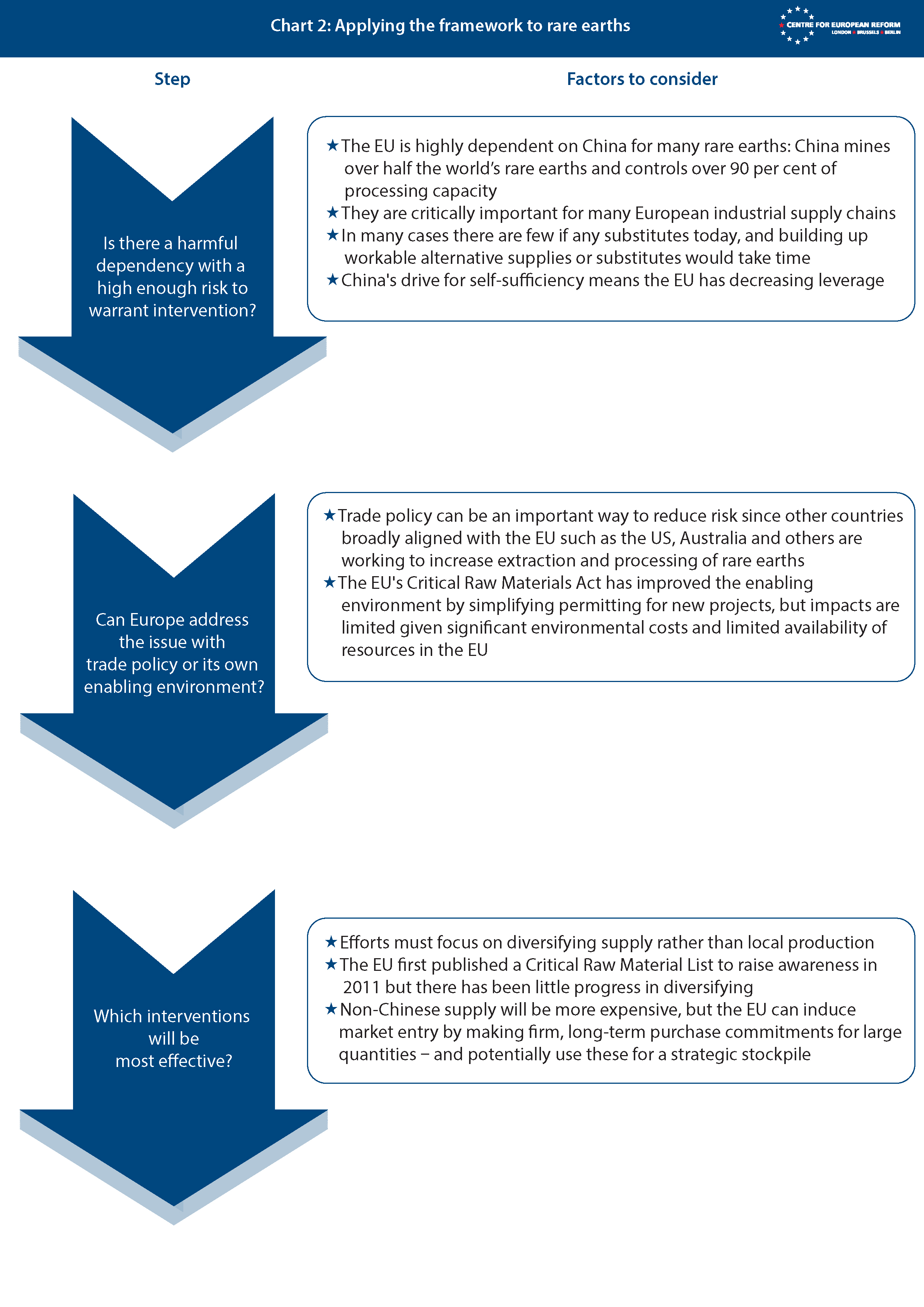

Is there a harmful dependency?

China dominates the extraction and processing of these elements as a result of decades of investment and willingness to accept the high levels of pollution associated with the industry. As a result, China has the lowest cost-base and the best refining technology. It also has a track record of both using its market power to shut out competition by lowering the price and subsequently using its dominance of the industry as strategic leverage in trade relations with the US and the EU.

Without reliable access to REEs, European manufacturers, including critical sectors such as cleantech, aerospace and defence, are at a critical disadvantage.

European companies have encountered difficulties due to China imposing export restrictions on REEs as well as certain other minerals dominated by China such as gallium and magnesium. REEs are a prime example of a harmful dependency since they fulfil essential criteria:

- REEs are critically important for manufacturing

- REEs are dominated by a single country

- That country has shown willingness and ability to weaponise that dependency.

Moreover, it takes time to build up alternative supply chains – obtaining mining permits in Europe is difficult due to environmental concerns and geological availability is also limited. The EU first started publishing a Critical Raw Material List, including REEs, in 2011 to highlight critical dependencies, after Japan was targeted by Chinese export restrictions in 2010. This was followed by the Critical Raw Material Acts (CRMA) in 2024, under which the goal is for the EU to mine 10 per cent, process 40 per cent and get 25 per cent of EU needs through recycling. However, so far only very limited progress has been made. Without reliable access to REEs, European manufacturers, including critical sectors such as cleantech, aerospace and defence, are at a critical disadvantage.

This year, China has announced a sweeping new export restrictions regime on a number of sensitive goods, including REEs. These restrictions include licensing for exports, as well as for re-exports of products that include as little as 0.1 per cent of Chinese materials. This would mean, for instance, that if a German producer wanted to export a wind turbine to the US that included a minimal amount of REE it would require a Chinese licence to do so. It is clear and obvious case of a harmful dependency that leaves Europe vulnerable to Chinese coercion.

European manufacturers have recently also felt the consequence of Chinese export restrictions, which have had a significant impact on their supply chains. It is not unreasonable to assume a significant effort from European companies to derisk their supply chain to avoid the political risk associated with the new Chinese export regime. Such efforts are already underway in certain sectors. However, there are compelling reasons to believe that a public sector intervention could be helpful. Lead times for setting up rare earth production and refining are long – up to a decade according to some estimates. And China can ease export restrictions when their competitive position is under threat, allowing them to overwhelm start-up competitors before reasserting their market power. The combination of long lead times and the Chinese cost advantage is a powerful disincentive to invest.

Last, but not least, Chinese products have a cost advantage that will always provide an incentive for manufacturers to use their product to cut costs and remain competitive. Companies that use alternative products will have to pay more and be at a competitive disadvantage in the global marketplace. There is thus a collective action problem that is difficult to overcome.

China has demonstrated that while it has a technological lead and is unbeatable on cost, it cannot be trusted as a dominant supplier due to repeated use of export restrictions as a political tool. Alternative suppliers would however face a dominant competitors with a technological lead, willing to use market power, both to remove competition by flooding the market at low cost, and at other times, to use export restrictions as leverage.

Can trade policy or changes to the enabling environment address the issue?

REEs represent a clear risk that market participants have so far failed to address, and the long investment horizons and competitive pressures create obstacles for them in doing so. The impact and strategic value of REEs are outsized given the small economic size of the sector: REEs are essential and extremely difficult to replace from a technical perspective. Disruption in supply entails disruption to much larger sectors and the wider economy. In recent years, the value of EU imports of REEs have never exceeded €150 million and no more than 20,000 tonnes are imported every year. So REEs is technically indispensable but monetarily marginal. This, combined with ongoing efforts in other countries such as the US, Australia and others to increase production, means that with the right incentives and policy consistency the ECF can help address this problem.

By making firm purchasing commitments for REEs, the EU can both incentivise other actors to enter the market and reward ongoing efforts to develop new resources.

The EU already has the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which aims to reduce dependence by supporting EU projects, simplify permitting processes, monitor developments and set goals for European extraction, refining and recycling of critical materials. These steps are useful, but the significant environmental costs and limited availability of resources will likely limit what is possible to achieve under the CRMA.

Similarly, trade policy is unlikely to address the issue because suppliers in other countries face similar competitive disadvantages compared to the Chinese. Although the CRMA does contain some elements that aim to boost international trade, these are unlikely to prove fruitful as the CRMA does not put any fresh money on the table, relying instead on diplomatic efforts such as the Clean Trade and Investment Partnerships with no binding commitments. The Commission has made other efforts, such as through the EU Energy and Raw Materials Platform, which matches suppliers and buyers of strategic raw materials, including REEs. But this type of co-ordination still relies on the private sector being willing and able to carry the cost.

Designing effective interventions

If Europe wants a secure non-Chinese supply, it will have to pay for the privilege. Chinese products are currently cheaper and there is little trade policy and market access negotiations can do to counteract that: new sources of supply of REEs from other markets are unlikely to be cost-competitive with Chinese products given factors like China’s production scale and its market dominance: China mines over half the world’s rare earths and controls over 90 per cent of processing capacity.33

By making firm purchasing commitments for relatively large quantities of REEs from trusted sources at prices well above current market prices the EU can both incentivise other actors to enter the market and reward ongoing efforts to develop new resources. This kind of offtake system would be similar in principle to programmes run by the US Department of Defense, but should not be limited to military needs since it needs to provide sufficient supply to reduce the risks for European civilian manufacturing. The purchases made can then be used to build up a strategic reserve in case of disruption – an annual supply could be set aside at a modest cost, and then the remainder could be resold into the market at a loss. The US, for example, is looking to stockpile approximately $1 billion in critical minerals to reduce its dependencies on China: a relatively small sum for a stockpile exceeding US annual imports, given the important role these inputs play in producing everything from fighter jets to smartphones.34 Given Chinese export restrictions, the private sector is already looking for alternatives, but public funding can help ease the transition and provide a long-term strategic guarantee for new entrants into this market.

It is important for the profit to be sufficiently large to induce new investment. It is better to accept excess profit in the beginning to make sure there is a gold-rush effect and spur investment. To do so, the programme must also have a large enough volume and duration. A 20 year-programme would cover a typical investment horizon, and the price and excess profit can be reduced towards the market price over that period. Ideally, it would be co-ordinated with similar efforts in countries like the US and Japan, but even a standalone programme could make a significant difference at a relatively modest cost given the small size of the market, the large-scale impact of disruption and Chinese ability and willingness to use market power as leverage.

Case study 2: Cloud computing

A further area of considerable policy attention and fears of harmful dependencies is cloud computing. Cloud computing is a technology which allows customers to access computing resources – such as data storage and processing power – remotely. It also allows these resources to be shared across many customers, enabling these customers to easily scale their requirements up or down without investing in IT infrastructure themselves.35 Different forms of cloud computing offer different features, such as dedicated or shared resources, and access only to basic infrastructure or services such as a platform to develop cloud-based applications, or to directly access software (such as the Microsoft 365 office productivity suite of software).

Is there a harmful dependency?

Currently, approximately 60-70 per cent of Europe’s cloud computing needs are provided by US companies – including the three ‘hyperscalers’, Microsoft, Google and Amazon, with only a small market share held by European cloud computing firms such as OVHcloud or by firms from other parts of the world such as China.

Cloud computing is a strategic technology, given both its potential to enable digitalisation, and that it can involve hosting sensitive and business-critical information.

While this is not an overwhelming dominance, the consequences if Europe’s dependency were weaponised could be severe – recent outages from some of the largest US players, which disrupted many businesses, have shown that concentration in the market carries potential for significant economic damage even from unplanned disruption.36 Cloud is increasingly recognised in Europe as a strategic technology, given both its huge potential to enable digitalisation, and the position of cloud computing companies, which may host extremely sensitive information and on whose software businesses and public sector administrations increasingly depend. Even before transatlantic tensions increased under the current US president, for many years some European policy-makers have also been concerned about the ability of US intelligence agencies to gather data on European businesses and governments via US cloud companies. Now, fears are growing about the potential for Washington to trigger a “kill switch” to paralyse many European cloud customers in the event of a major policy dispute with the US.

The prospects of quickly switching suppliers in the event of a supply problem are not good, moreover. As the largest cloud computing firms increasingly tie software and value-added services to their cloud environments and as business customers’ IT staff specialise in one particular cloud environment, these business customers can find themselves ‘locked in’ to their existing cloud computing provider. It can then be difficult to switch without making very large investments (such as to retrain staff or manage the migration of data which may not be easily intelligible by the new cloud provider) and potentially losing important functionality. Consequently, even large and sophisticated ICT firms such as OpenAI have only been able to switch cloud computing providers over an extended period.

Given the proprietary nature of the software produced by cloud computing companies, it is not straightforward for European (or other non-US) firms to step into the cloud computing market at scale, or for many EU customers to self-supply ICT resources. There are therefore limited full alternatives that could emerge quickly enough to respond to an immediate threat; although the presence of somewhat successful European cloud firms like OVHcloud and Schwarz Group (albeit with far less scale than the hyperscalers) suggests that European cloud companies could eventually provide at least some of the services of the hyperscalers (particularly at the infrastructure and platform levels, if not replicating all their software), albeit that it would take time and investment for them to be in a position to have sufficient computing capacity.

Assessing the actual level of risk is less straightforward. On the one hand, the EU’s relationship with the US is increasingly tetchy, particularly in the area of digital regulation, and the US administration has become less predictable and less rule-bound. Furthermore, while the EU remains heavily reliant on the US for security guarantees, the EU’s leverage in transatlantic policy disputes remains questionable, as evidenced by the recent US-EU trade deal which was widely recognised as one-sided. On the other hand, the hyperscalers make more than half their revenue outside the US and the EU remains their most important foreign market by some margin. Weaponisation of reliance on cloud computing services would undermine trust in these firms globally, and would likely lead to strong policy reactions from other parts of the world which are already adopting ‘digital sovereignty’ policies. Furthermore, the EU is a net exporter of ICT services, including to the US, thanks to its strengths in areas like advanced software solutions (like enterprise resource planning, customer relationship management, business intelligence and supply chain management software, as well as in specialised software solutions for areas like travel and security) and in networking and telecommunications services.37 The success of unsung European services giants like SAP, Ericsson, Nokia, Amadeus, and several of Europe’s largest telecoms firms implies that the dependency may not be as unilateral as it first appears.

Nevertheless, given these factors, it does not seem unreasonable to consider that the EU has a harmful dependency, albeit one which may not be as urgent to address as those with countries who are more unambiguously hostile to fundamental European interests.

Promoting greater awareness of political risk among EU cloud computing customers remains an important step.

Improve the enabling environment

If the EU ought to prioritise developing a cloud computing sector which can compete head-to-head with the US hyperscalers, then its first priority should be to identify whether improvements to the business environment in Europe could help. Here, European tech firms face a litany of major obstacles, many of which have been laid out in the Draghi and Letta reports, or have been raised repeatedly by business groups across the EU in recent years. Addressing many of these problems will be necessary to help Europe’s own cloud computing sector grow. Some of the most important reforms include:

- Simplifying the complex regulatory environment for the digital sector, which is replete with overlaps and inconsistent objectives, and is increasingly difficult for even sophisticated European tech firms to navigate.

- Considering whether the underlying regulatory standards and expectations imposed on EU tech firms are proportionate and sufficiently innovation-friendly. The AI Act, for example, has been relentlessly criticised since its adoption for making it harder – and in some cases uneconomic – to adopt AI in sectors and environments where it has enormous economic potential. In particular the use of AI to optimise cloud computing infrastructure may be subject to onerous obligations. And the GDPR, which is increasingly applied in rigid and uncompromising ways, poses an increasing challenge for companies like cloud computing providers who will often store or process personal data.

- The lack of a single market in the digital sector, which is characterised by divergent implementation by different regulators in different member-states. This makes it difficult for providers to scale up, to provide services seamlessly across the EU, to offer the same services to all European customers, and to rely on a single set of infrastructure.

- The need for well-functioning capital markets to provide funding and boost access to capital for businesses like cloud computing providers, which often need to operate at a loss while they grow and obtain an economic level of scale.

- Barriers like planning laws which can make it difficult for cloud computing firms to invest in large-scale infrastructure like data centres.

Importantly, none of these require funding from the ECF to achieve – yet they are likely to be significant constraints on the emergence of large-scale cloud computing companies in Europe that can compete with the US giants.

Designing effective interventions

Given the urgent steps needed to enable an environment in Europe where cloud computing companies can succeed, the case for making more intrusive interventions in the market at this stage requires careful balancing of trade-offs.

Promoting greater awareness of political risk among EU customers, so that they can take these into account when making sourcing decisions, remains a potentially important step. For example, as noted above, US hyperscalers are already offering a range of ‘sovereign cloud’ solutions which aim to eliminate or at least mitigate many of the political risks which some EU customers are fearful of. These options include ensuring European data is stored and processed in Europe; running the European cloud operation through a separate subsidiary with its own board comprised of Europeans; providing facilities to ensure if needed that European cloud operations could be handed over to Europeans and operated independently; and operating joint ventures with European cloud firms.