Will the unity of the 27 crack?

- To date, the EU’s position on Brexit has held firm. During the talks over the terms of the divorce, the interests of the member-states were aligned and the UK could not rely on dissenting voices to soften the hard line pushed by Germany and France. But in the second phase of the Brexit negotiations, the differing economic and political interests of the various member-states may emerge. Some believe this may threaten the unity of the 27.

- This policy brief argues that the EU will continue to stick together. The UK will not be offered a ‘sweetheart deal’. The only way for Britain to maintain a comparable level of single market access to that which it enjoys today would be for Theresa May to soften her red lines and accept the accompanying overarching obligations. If she is unwilling to do so the UK should expect little more than a basic free trade agreement (FTA), which at its most ambitious would be of similar depth and scope to the early European visions of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), the ill-fated EU-US free trade agreement.

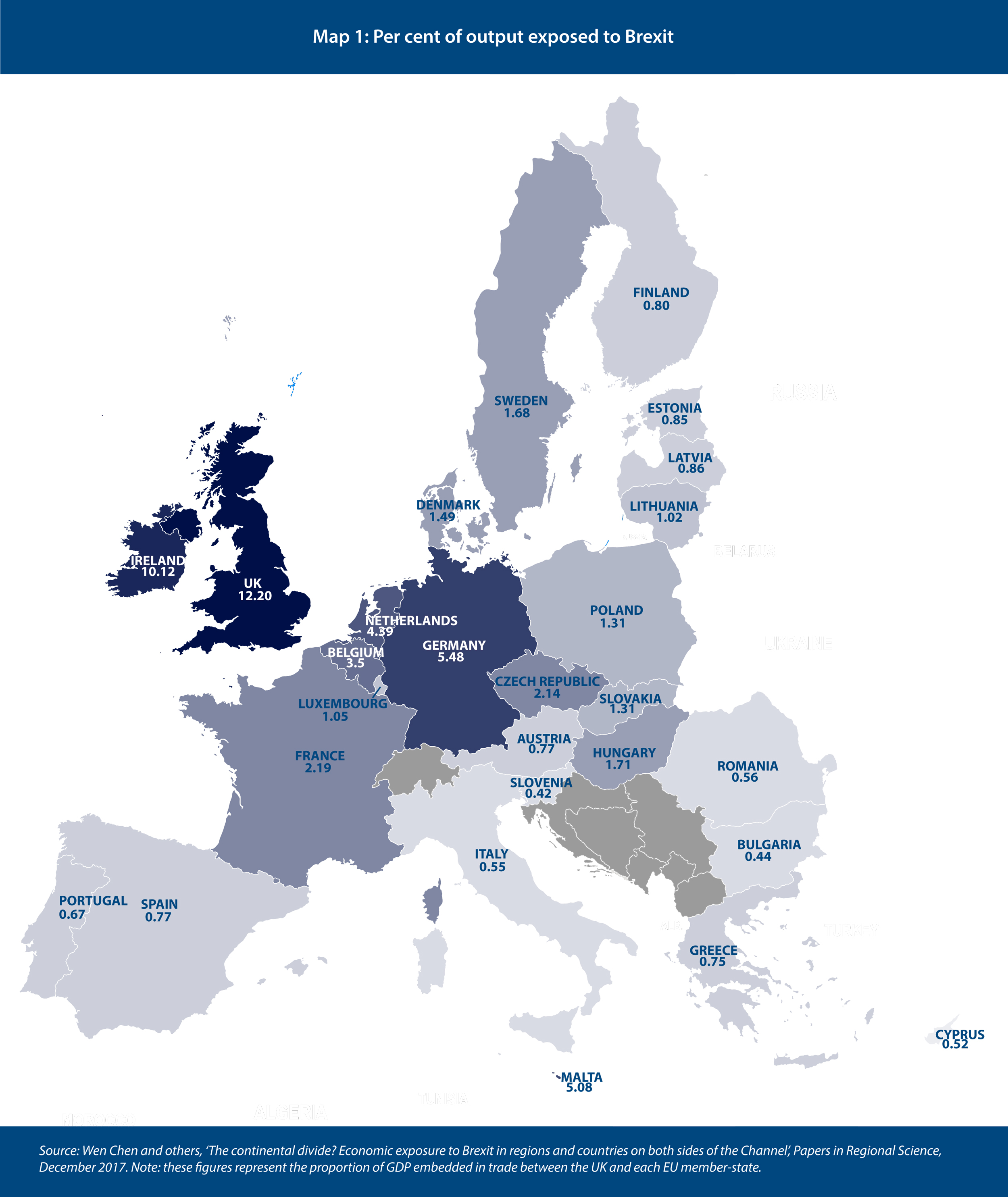

- While the EU-27 economies are indeed exposed to Brexit, the majority of the 27 face small economic costs from the process. Germany’s economy is the most exposed, after Ireland, but it has proved one of the toughest countries in the negotiations. Apart from Ireland, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and tiny Malta, 2 per cent or less of the member-states’ GDPs are embedded in trade with the UK. While more exposed free trade advocates like the Netherlands might countenance a softer approach for economic reasons, the integrity of the single market remains an important concern and most member-states are unlikely to expend much political capital on the UK’s behalf.

- The City of London’s status as Europe’s largest financial centre provides Britain with some leverage, but not as much as the UK appears to believe. Where Brexit poses risks to banks and businesses in the 27, the EU has the power to contain the fallout from a loss of access to the City by providing equivalence, either for a temporary period after the transition to give financial markets time to adjust, or permanently. But the scope of that equivalence will be much more limited than the access provided by single market membership.

- While a British offer of a preferential migration regime for EU citizens would certainly earn goodwill, officials in Brussels point out that, without EU law in operation in the UK, promises made now by the UK do not bind the hands of future governments. Future governments might choose a more restrictive migration regime.

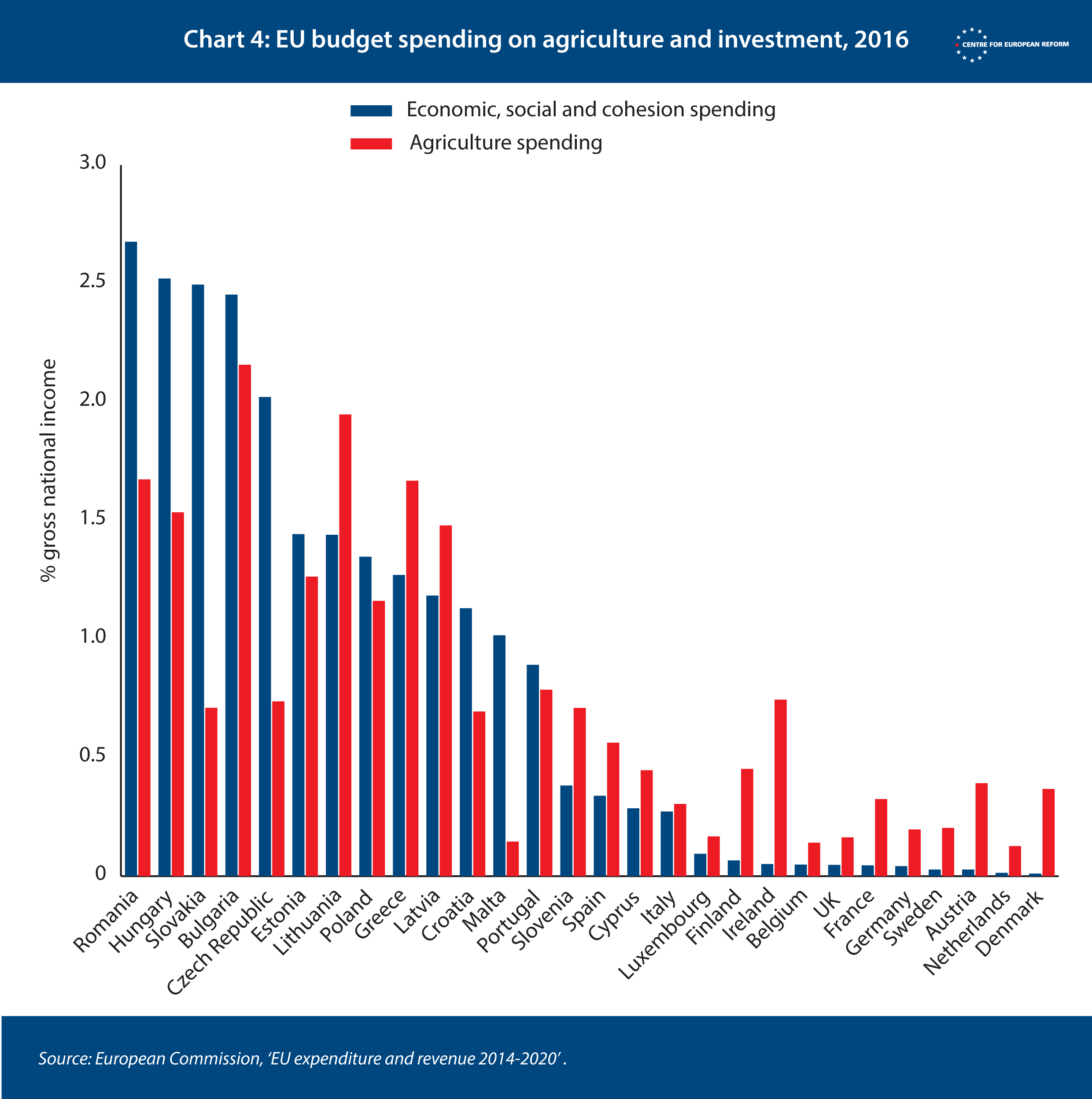

- One area the UK might find worth exploring is future budget contributions. The politics of the EU budget are going to be especially difficult in the next round of negotiations, and if the UK offered a significant sum, it might unlock some benefits in the negotiations over a free trade deal. However, these benefits would be constrained by the UK’s red lines on accepting EU rules, the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and free movement.

“Each of us can have our own interests. That’s what the prisoner’s dilemma is all about”, warned French President Emmanuel Macron at the start of 2018. “Everyone can have an interest in negotiating on their own, and think they can negotiate better than their neighbour. If we do that … collectively we will create a situation which is unfavourable to the European Union and thus to each one of us.”1 German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker have also cautioned against infighting among the 27, now that the negotiations are moving on to the transition and the framework for the long-term relationship.

The EU had almost perfectly aligned interests during the divorce negotiations, with all countries wanting the UK to pay the Brexit bill, seeking to retain rights for their citizens living in the UK, and happy to let Ireland shape the negotiations over the Irish border. But the member-states have different interests over international trade, finance and migration. France, Germany and the European Commission have concerns that the 27 could diverge, with some pushing to offer the UK a sweetheart deal, especially if the UK tries to drive wedges between them.

But what would a sweetheart deal look like? We define it as one that provides more access to the EU’s internal market than UK acceptance of EU obligations would ordinarily allow. For example: the same single market access as Norway enjoys through its membership of the European Economic Area, but without freedom of movement. Or alternatively, a continued high level of financial market access for UK banks, but with the level of obligations demanded of Canada in its free trade agreement with the EU, vis-à-vis regulatory harmonisation and supranational oversight.

Despite some differing economic and political interests, the EU-27 are unlikely to split in phase two of the talks.

Three arguments are usually put forward to suggest that the EU-27 may split in the second phase of the Brexit talks. The first is that some member-states are uncomfortable with the tough line taken by the European Commission, France and Germany; for ideological reasons, the more economically liberal countries do not want to see trade barriers rise. Some member-states conduct a lot of trade with the UK and so do not want trade barriers as a matter of national interest. And some run trade surpluses with Britain that they want to protect.

The second argument is that the City of London’s status as Europe’s largest financial centre provides Britain with leverage. If the 27 found it harder to access London’s investment banks, funds and capital markets, the cost of capital would rise for continental businesses, lowering investment and growth. What is more, not all member-states would benefit from City business relocating to the EU as a result of Brexit – the biggest beneficiaries would be Frankfurt, Paris and Dublin. Ultimately, the story goes, some member-states will press for a trade deal that provides comprehensive access for City firms – perhaps based upon mutual recognition of regulations, or failing that, a unilateral acceptance by the EU that Britain’s rules are equivalent.

The third argument is that a substantial British contribution to the EU’s coffers would force Germany and France to show the colour of their money. In her Florence speech in September 2017, Theresa May said that “we will also want to continue working together in ways that promote the long-term economic development of our continent”, and that “this includes” – as opposed to being limited to – paying for special programmes like scientific research. She did not repeat her vow to end “vast contributions to the European Union”, made at Lancaster House eight months earlier. Were May to agree to pay funds for the economic development of Central and Eastern Europe, this might encourage the region – and net contributors to the EU budget in Western and Northern Europe – to put pressure on France and Germany.

These arguments are overdone. While some countries would certainly be willing to offer Britain a sweetheart deal, they are either too small (Ireland), too isolated diplomatically (Poland and Hungary), or the economic fallout from Brexit is not large enough to make them risk their relationships with other EU member-states (most countries). In this brief, we explain why the EU-27 is unlikely to split in phase two of the talks, and why the EU will continue with its tough line. First, we examine why France and Germany have been maintaining a firm line on Brexit.

The Franco-German line on Brexit

The dominant line from the EU so far has been the Franco-German mantra of unity, integrity and indivisibility. This is underpinned by the European Council guidelines of April 2017, which mandate that “there can be no cherry-picking” of the ‘four freedoms’ of goods, services, capital and people, and that “the Union will preserve its autonomy as regards its decision-making as well as the role of the Court of Justice of the European Union”.2 Angela Merkel insisted in November 2016: “If we were to make an exception for the free movement of people with Britain, it would mean we would endanger the principles of the whole internal market.”3

Merkel will put this principle above narrow trade and business interests. Although German industry stands to lose from a hard Brexit, Germany sees the integrity of the European Union as a core national interest, embedded in Article 23 of the German constitution.4

France and Germany are willing to take a modest economic hit for the sake of their core strategic interest – the European Union.

Like Germany, France has some core economic interests at stake, but Macron takes a similarly tough approach to Brexit. He has described his stance as “strict”, declaring his opposition to “a tailor-made approach where the British have the best of two worlds.”5 France and Germany view themselves as the custodians of the European project. They fear that any deal that allows the UK partial integration with the single market could entice further exits, and could ultimately “kill the European idea”, as Macron puts it. Paris is already making a play for London’s banks by reducing payroll taxes on high salaries, and giving tax breaks to well-paid expatriates to encourage financial institutions to move people. And as with Germany, while some French businesses will face disruption, economic costs will be offset by the political upside of repatriated jobs.

As large countries, with highly diversified economies and strongly pro-European governments, France and Germany are robust enough to withstand the economic costs of Brexit, and are willing to take a modest economic hit for their core strategic interest – the European Union. For fairly obvious reasons, the European Commission – whose Brexit taskforce led by Michel Barnier is charged with negotiating the divorce, transition and framework for the future relationship – follows the Franco-German line. It sees its role as guarding the interest of Europeans as a whole, and generally takes a federalist view of European integration.

This hard line continued in the March 2018 draft European Council guidelines, written by the Council of Ministers’ secretariat, which reiterated the no cherry-picking mantra, saying that there could be no “sector-by-sector” participation in the single market.6 The guidelines are subject to revision, but drastic changes without some major concessions from the UK are unlikely.

Those guidelines suggest that the best free trade agreement achievable would be similar in scope and depth to TTIP. Such an agreement could:

- Ensure all goods continue to be traded tariff-free (with question marks over agriculture);

- Create new barriers at the border, although the frequency of checks and bureaucracy for business could be mitigated by mutual recognition of conformity assessment bodies and equivalency rulings in specific areas where appropriate (for example, food and plant hygiene);

- Commit the EU to open its services market to the same extent as the EU-Canada agreement which largely re-states the EU’s WTO commitments on services. The trade deal might be accompanied by separate equivalence rulings, made unilaterally by the EU, in areas of finance that are deemed to pose low systemic and consumer risk, and an adequacy ruling on data;

- Recognise UK professional qualifications in non-sensitive areas;

- Create an ongoing regulatory dialogue to ensure no unnecessary barriers are erected as a result of future legislation;

- Contain a non-regression clause holding the UK to existing levels of adherence to state-aid, competition and environmental rules;

- Sit alongside separate agreements on aviation, energy, security and defence, as well as a preferential migration scheme dealing with issues such as business visas.

In the context of a free trade agreement, the EU’s ability to further liberalise trade in services is constrained by commitments made in previous agreements. If the EU strikes a better deal on services with another country, it is bound to offer the same level of access to existing FTA partners such as Korea and Canada. And the EU is unwilling to set a new benchmark for future FTAs with other countries by providing a better deal for Britain. So even though a few member-states might be tempted to offer the UK more access than others, the fear of other countries demanding upgrades will keep desires in check.

These upgrade clauses in trade agreements can be avoided, but only if there is sufficient alignment of regulation (‘approximation’). The EU’s association agreement with Ukraine does not trigger upgrades in other trade agreements, for example, because regulatory approximation is far-reaching. The Ukraine deal provides high levels of market access in exchange for Kyiv’s adoption of much of the EU’s acquis. But such regulatory approximation would involve the harmonisation of rules, and adherence to accountability structures, that takes the EU-UK partnership out of an FTA scenario and into a high access, high obligation relationship.7

On the face of it, we might expect smaller countries to consider a more far-reaching agreement than the European Council’s draft guidelines point towards, especially those with close economic and political ties to the UK. But a closer look at the trade and financial evidence should dampen British hopes that they will be able to divide and rule in the second phase of the negotiations.

Trade

The EU is the UK’s most important trading partner. With the exception of Ireland, other member-states have much less to lose than the UK.

Gross export and import data tell us very little about a country’s actual exposure to Brexit. This is due to the complex back-and-forth nature of modern supply chains. To give an example:

- A British car is sold to France for £1,000;

- The car is then painted blue, and sold back to the UK for £1,100;

- While the gross figures suggest France has exported a car worth £1,100, in reality the domestic added value is only £100;

- If this supply chain were to break down, and the car were no longer sold back to the UK, the hit to French GDP would be £100, not £1,100.

Brexit will impose costs upon the 27, but the pain will not be enough to provoke dissent from the Franco-German line.

A group of academics from the UK and Netherlands have used value-added data to measure how exposed different countries are to Brexit.8 Their work does not attempt to quantify how much damage Brexit will do – that depends on the nature of the future relationship – but instead shows the share of GDP that is embedded in trade flows between the UK and the 27. In doing so, it gives a good indication as to which countries have, potentially, the most to lose from Brexit.

The country most exposed to Brexit is the UK (12 per cent). The only member of the 27 that comes close is Ireland, with 10 per cent of its GDP exposed to Brexit. This is not surprising. The UK only accounts for 16 per cent of Ireland’s trade, but Ireland is an exceptionally open economy, it has close economic ties to the UK in sectors such as finance and agriculture which would be badly hit by a hard Brexit, and it shares a land border with the UK.9

Dublin is pushing to prevent a hard border with Northern Ireland. In December 2017, Theresa May conceded that if no other solution was found, Northern Ireland would continue to align with EU regulation necessary to prevent a hard border. That would suggest that Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which props up the Conservative minority government in Westminster, would come under heavy pressure to accept Northern Ireland remaining in the customs union and other EU rules and agencies necessary to prevent border checks. The European Commission spelled out this option in detail in the draft withdrawal treaty, published in February 2018.10 But this would probably prove unacceptable to the DUP and Conservative hardliners. If such a stand-off emerged, senior figures in the EU say that while they might encourage the Irish to accept minimal checks, probably close to rather than on the border, if Dublin remains firm in demanding no infrastructure of any sort, the 26 will stand behind Ireland and push the UK to keep Northern Ireland in the customs union and single market for goods.

So long as Ireland is pushing for unique all-island solutions to prevent the emergence of physical customs infrastructure, Ireland is unlikely to exhaust its political capital on the future relationship by arguing for the UK to be granted near-equivalent market access to now, minus the obligations. However, Dublin will probably press for a free trade agreement that covers as many sectors as possible, especially agriculture, and for a closer relationship in services than the EU’s usual practice. (As we discuss below, even the most comprehensive free trade agreement in services would fall far short of single market membership.)

For the most part, the other member-states have much lower exposure to Brexit. Germany (5.6 per cent) and the Netherlands (4.4 per cent) have greater exposure than most, thanks to the enormous scale of both countries’ exports of manufactured goods. But, apart from tiny Malta, the other member-states’ economies are not particularly endangered by Brexit.

While Brexit will hurt everyone, it is clear that the acute risk associated with a dramatic fall in EU-27-UK two-way trade is concentrated in two countries only: the UK and Ireland. All of the others would potentially suffer, but to a much lesser degree.

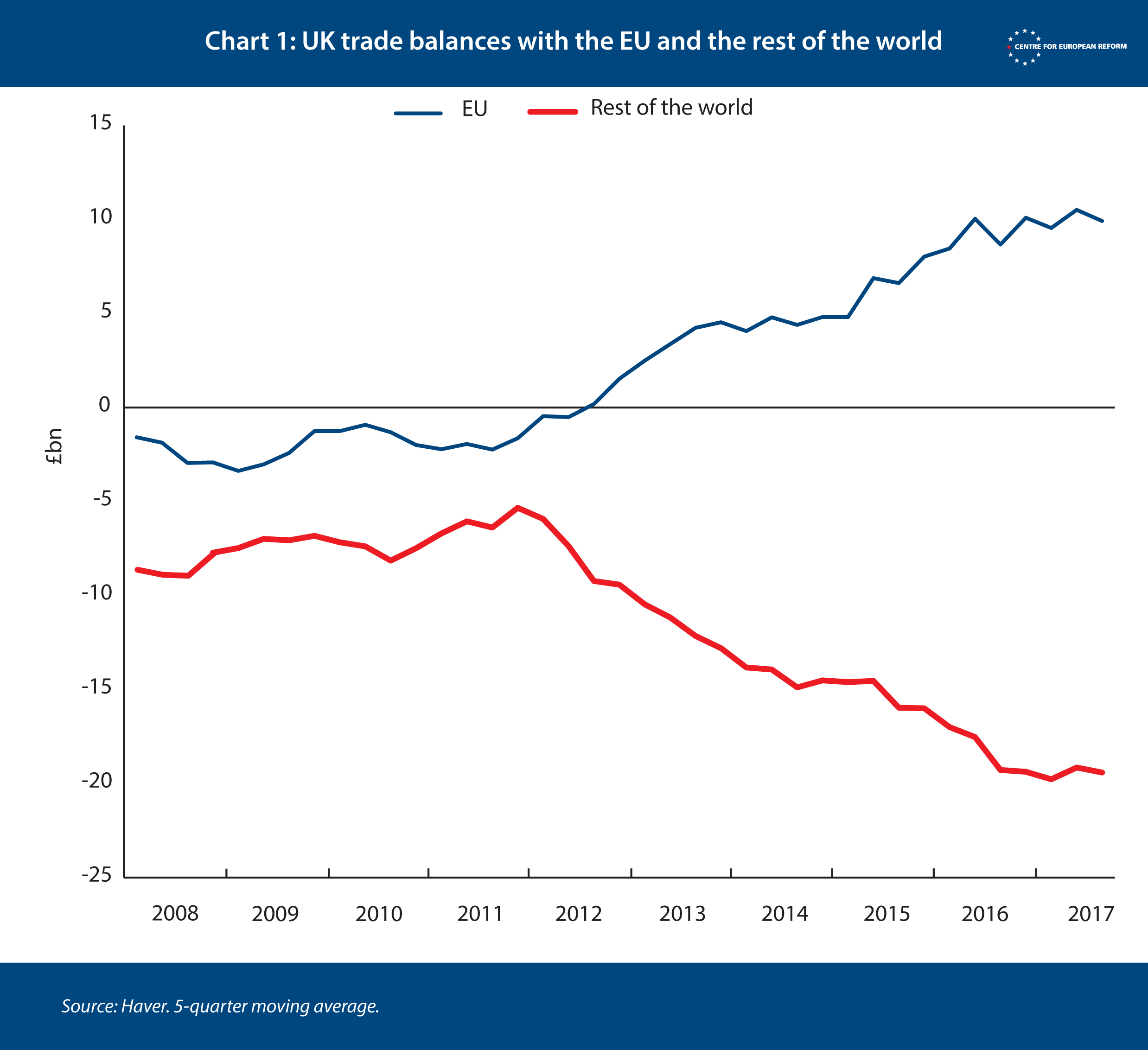

What of the argument that member-states will be keen to protect their trade surpluses with the UK? On the face of it, it has some merit. The UK’s trading relationship with the EU has become severely imbalanced since the start of the eurozone crisis in 2010. But the UK would be wrong to assume that it can split the 27 in the phase two negotiations as a result.

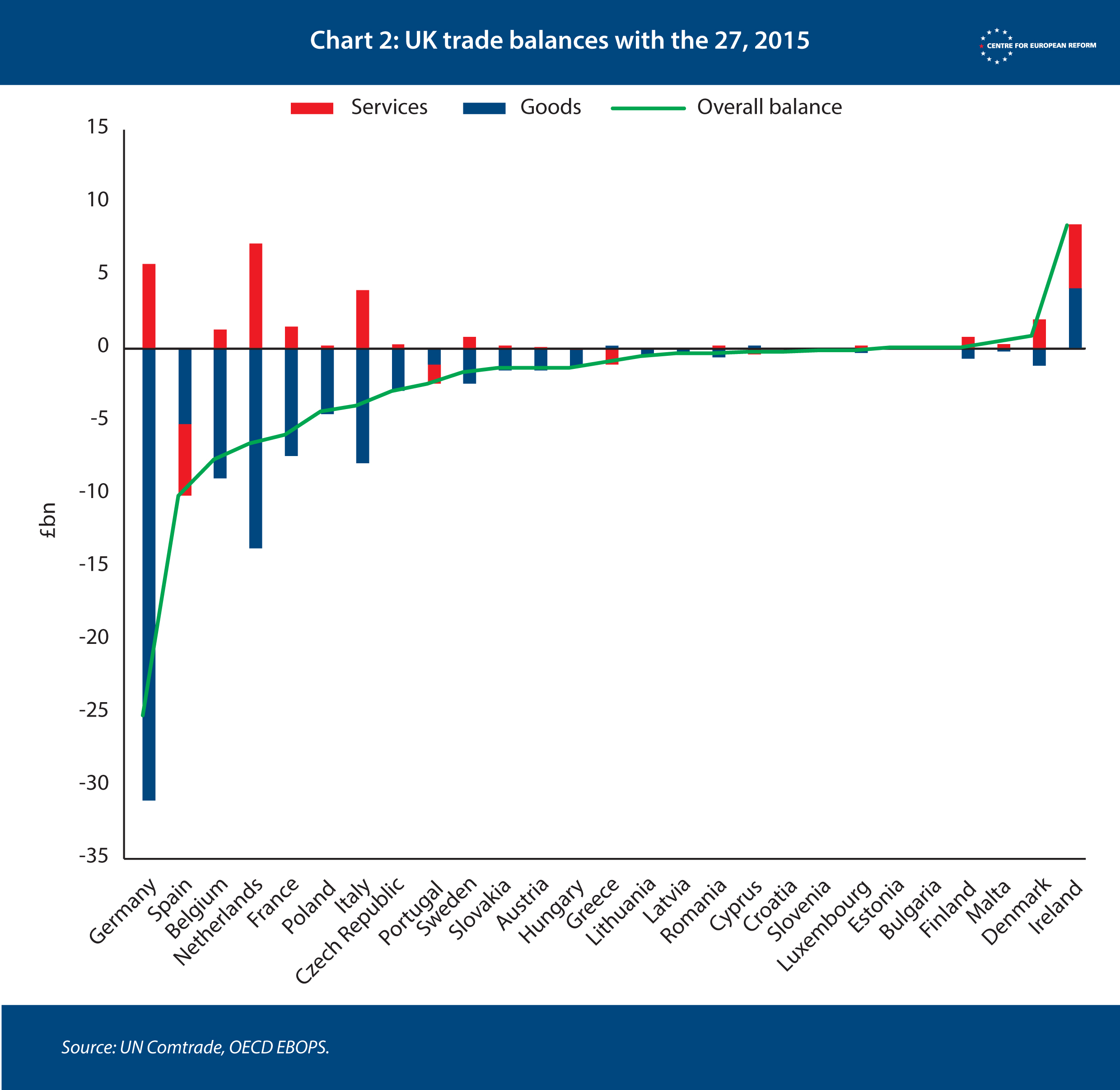

As a result of the comparative weakness of its manufacturing sector, the UK runs sizeable deficits in goods trade with Germany, Spain, Belgium, France, Poland and Italy, which is partly offset by surpluses in services (but not with Spain, where Britons’ holiday spending is a good source of revenue) (see Chart 2). The countries with the largest surpluses are Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, which together make up more than half of the 27’s overall surplus with Britain.

As noted above, Germany’s strategy for Brexit has been clear from the start – that it will be uncompromising in order to protect the single market, a strategic interest. Belgium is one of the most federalist member-states, and has historically been critical of Britain’s attempts to block closer EU integration. But the UK is a big trade partner, and Belgium has a stronger interest than most member-states in low trade barriers with the UK. The Netherlands has been a closer ally to the UK in EU balance-of-power politics, and is more pro-trade than Belgium; its diplomats say they want the EU’s future relationship with the UK to be very broad. But it remains to be seen whether the country will be willing to stick its neck out in negotiations with Britain, especially since its economy is very closely integrated with that of Germany.

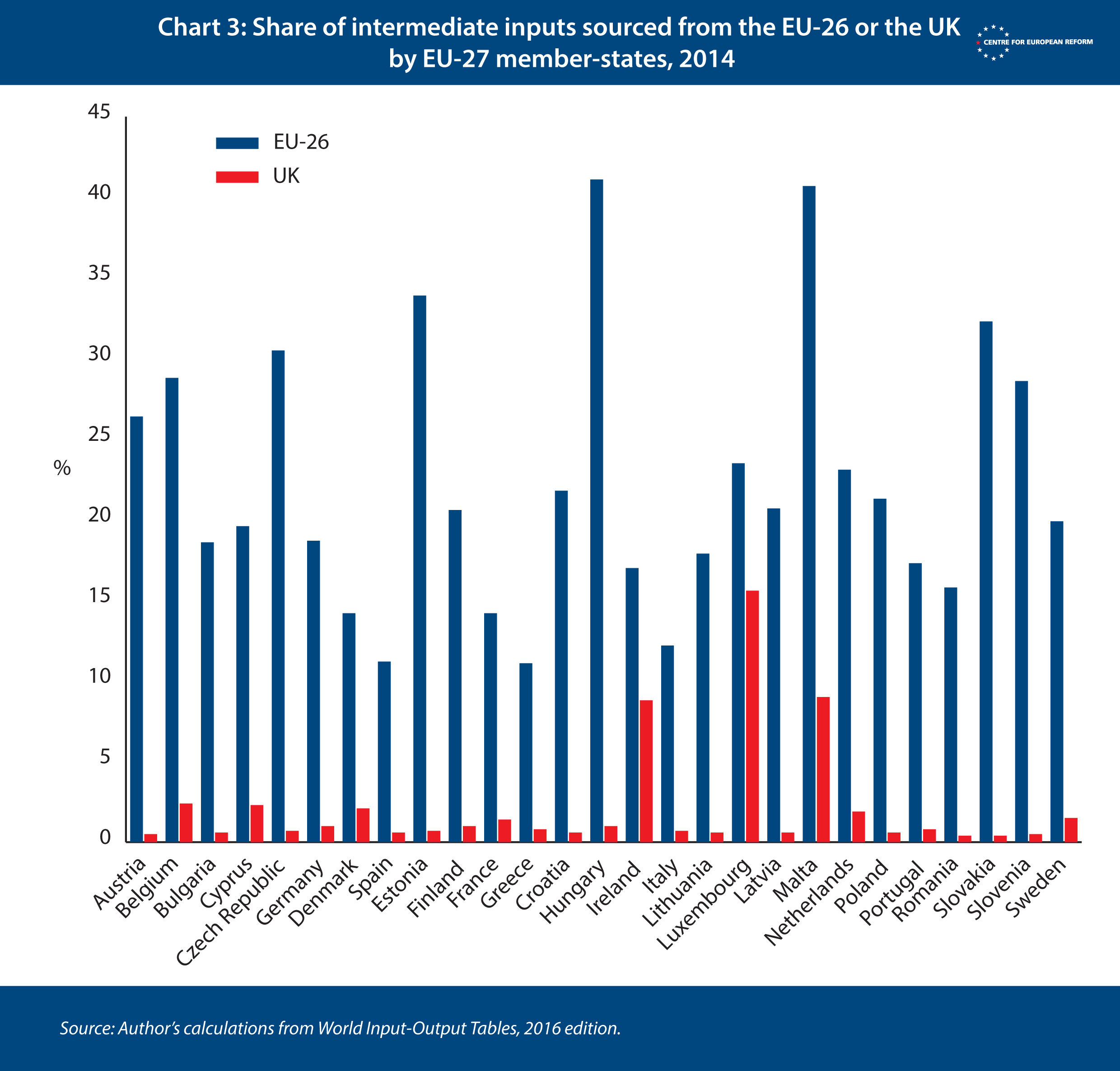

Bilateral trade balances between EU-27 and the UK are poor measures of their strategic interests, in any case. All 27 member-states, apart from Malta, conduct more of their trade with the EU than with the rest of the world. The EU is one of the world’s three major economic regions (alongside NAFTA and East Asia) in which unfinished goods criss-cross borders before being packaged and sent around the globe. And the exports of the EU-27 are more reliant on ‘intermediate inputs’ (components that make up final products) sourced from their fellow 26 member-states than on inputs from the UK. (See Chart 3.)

Other than in Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta, the UK’s relative share of EU-27 intermediate inputs is tiny. Ireland can be explained by its proximity and historical ties; Luxembourg and Malta, in part, by their approach to taxation.

The single market’s rules protect value chains that criss-cross borders, with components manufactured in one country, combined with other inputs from across the market, and assembled in others. The 27 do not want to lose access to UK inputs in their production processes, but protecting the single market is a stronger strategic interest. Allow one country to opt out of some parts of the single market, and a precedent will be set that might prompt other member-states to demand ‘opt-outs’, and countries outside the EU to demand ‘opt-ins’. Brexit will impose costs upon the other member-states, but, apart from Ireland, the pain will not be enough to spur them to offer the UK a deal that undermines the four freedoms.

Financial services

British ministers – and London’s bankers – point out that the City is the world’s largest international financial centre. The City offers a wide range of financial products, and huge numbers of lenders, borrowers, buyers, sellers and insurers who participate in its markets from around the world. That makes it a cheap place to raise capital, borrow and insure against risks, because competition is strong. On January 9th, Chancellor Phillip Hammond and Brexit minister David Davis wrote in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that Britain was seeking a deal that ensures “collaboration within the European banking sector, rather than forcing it to fragment”, and that the deal should not “put hard-earned financial stability at risk”.11

But at a Centre for European Reform conference in November 2017, Michel Barnier chastised the British for being unrealistic in their simultaneous demands for “no changes in market access for UK-established firms” and for rules to be agreed by a “‘symmetrical process’ between the EU and the UK, outside of the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice”.12 He explained that this contradicted the April 2017 European Council guidelines for the Brexit negotiations which said that “the Union will preserve its autonomy as regards its decision-making as well as the role of the Court of Justice of the EU”.13

The UK’s red lines mean financial passporting is impossible – this is not mere punishment for Brexit, it is risk management.

Yet the Council guidelines also said that the future framework – the outline for the final arrangements that must be agreed before the UK leaves the EU – should “safeguard financial stability in the Union”. The British are trying to drive a wedge into the gap between the EU’s twin desires for autonomy over rule-making and financial stability. Will that work?

Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, has been trying to remind the EU-27 why financial centres arise: there are advantages to having banks, financial markets, and regulators concentrated in the City, because there is a big pool of skilled workers to choose from as both bankers and their watchdogs; and if banks, markets and other firms are large they can provide more capital and choice. UK officials also say that the City of London acts as the hedging capital of the EU. Continental banks use the City’s services to hedge against risks to their assets. They rely on short-term deposit financing and lend out, long term, on fixed interest rates. They need hedging instruments to ensure that their short-term financing needs are met if they struggle to attract deposits. If they are cut off from the UK market, then banks in the 27 are vulnerable to higher costs, because interest-rate derivatives trading will be more expensive.

For the EU-27, the calculation of their interests is tricky: the benefits of access to the big financial services cluster in the City, versus two sets of political risks. The first set would be giving the UK a deal that provides better access to the single market than anyone else, setting a precedent that could bring the US, Singapore, Japan and ultimately China to demand the same. The second set is the risk that the City suffers serious disruption, spreading financial instability to banks and markets in the 27, which is why the EU has been so guarded about allowing cross-border financial services from countries without EU regulation and supervision in force.

Michel Barnier has repeatedly said that the UK’s desire to end the operation of EU law and to leave the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice mean that financial passporting is impossible. (Banks can use a passport to open a branch in another European Economic Area country, while being regulated and supervised in their home country. That means they do not have to set up an expensive fully-capitalised subsidiary in every member-state.) This is not mere punishment for Brexit: the way the single market for financial services has been built is through harmonised rules, and minimum standards, to create a regulatory floor. This gives national regulators the confidence to know that foreign banks, funds and insurers serving their citizens are not going to rip them off or take too many risks. Without EU law in force, future UK governments, which do not favour Britain’s current strict approach to financial regulation, may choose rules that the 27 would not allow at home, exposing their domestic markets and consumers to risks that the 27 had not signed up to.

A free trade agreement that replicated single market terms could not be negotiated either. Financial regulation is constantly being updated, because finance is so fast-moving, with new products and institutions entering new markets. Free trade agreements are largely one-off treaties that set rules for a long period of time, rather than creating political institutions that will come up with new rules to deal with changing markets and risks. TTIP would have gone a little further, envisaging closer co-operation between US and EU regulators to ensure that new rules did not result in unnecessary future barriers, and to identify potential areas where equivalence rulings might be appropriate. The UK could potentially get something similar. But it should be noted that TTIP is on ice, and FTAs never get very far in their attempts to align regulations and standards. Ultimately, no one wants to cede power over regulation in a treaty; the only way is to have joint institutions that govern joint rule-making. And the 27 have little interest in setting up another set of EU-type institutions just with the UK, since that would dilute the autonomy of their own institutions.

Equivalence would allow the UK market access and regulatory autonomy, but its extent would be limited by the UK’s red lines.

Like the UK, the 27 face a trade-off between the benefits of access and the desire for regulatory autonomy. How can that be managed? After all, only a few countries will be welcoming émigré bankers from London – France, Germany, Ireland and, perhaps, Luxembourg. The other member-states will not profit from the jobs that move and the tax revenues that they will bring.

First, the transition period, which is set to last until the end of 2020, and may last longer, will also provide banks and other institutions with enough time to move operations to the 27, if needed, mitigating the loss of access to the City.

Second, the answer lies in equivalence – a unilateral declaration by the European Commission after Brexit that the UK’s rules are equivalent would permit cross-border imports of certain types of finance from the UK.

The EU would be able to decide, on a case-by-case basis, whether the access to the City would be worth the political costs and regulatory risks; and agree to equivalence if so. The EU does not recognise third country rules on banking and most classes of insurance as equivalent, and it would be unlikely to make an exception for the UK, although it does recognise rules governing clearing and settlement and some other activities in third countries. The EU may decide that it is better to allow clearing houses dealing in large volumes of euro derivatives to continue in London, at least until they have the market infrastructure to bring that business onshore.

Determining which areas of financial services should be granted equivalence may be a difficult process, with some member-states preferring greater access to the City than others. The UK will probably ask for a stronger system of equivalence than the EU’s current regime, in which the European Commission can withdraw equivalence rulings with 30 days’ notice. But without EU regulation and supervision in force, judging by its decisions with other third countries, the EU will be unwilling to provide access on markedly better terms than it does to the US.

Migration

The rights of EU citizens in the UK have been at the top of the EU’s negotiating agenda, and were largely secured in December 2017. Now the focus will move on to the UK’s future immigration regime, which has not yet been officially sketched out. The key question is: will Poland, Spain, Italy and other countries whose people have migrated to the UK in large numbers, be keen to give concessions on market access for goods and services, in exchange for a British migration system that provides preferential access to its labour market, but falls short of free movement?

The right to live and work anywhere in the EU is a big benefit to the people who make use of it. Governments are largely in favour of protecting the rights of their citizens. And remittances sent home by the citizens of poorer states in the EU provide a useful source of foreign currency earnings. For instance, in 2016 Polish citizens in the UK sent back £884 million in remittances, while Hungarian nationals sent back £339 million. 45 per cent of Cyprus’ remittances came from the UK in 2016.14

However, the big outflow of people from Central and Eastern Europe since 2004 has made the region’s bad demographics even worse, as most of those leaving were younger and better educated than the older generations who stayed behind. The IMF estimates that emigration from Central and Eastern Europe has slowed that region’s real GDP growth by 7 percentage points between 1995 and 2012, with high rates of skilled migration proving especially harmful to productivity growth. The loss of young workers pushed up spending on pensions, welfare and healthcare as a proportion of GDP.15 This is why Poland’s Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, said in a recent speech to parliament: “We are giving the gift of our greatest treasure, our citizens, to other countries: our bricklayers, engineers, plumbers, teachers, doctors or IT specialists. Quite obviously, this is not what we want.”16

A preferential migration regime for EU citizens could generate some goodwill but would not unlock significant market access.

Businesses in Central and Eastern Europe are struggling to recruit qualified staff. In the last two years, 80 per cent of Hungarian companies reported labour shortages impairing their productivity.17 The Polish government has implemented a ‘returns’ programme, to try to persuade skilled and educated workers to come home. Freedom of movement has not been an unalloyed good for sending countries like Poland (at least in economic terms). Nevertheless, freedom of movement remains a cherished benefit within the EU, and most member-states seek to maximise their citizens’ opportunities to move around. Offering a preferential immigration system for EU nationals could generate goodwill among the 27, and possibly unlock some greater market access for the UK. The UK House of Commons’ Exiting the EU Select Committee has tried to encourage the government to consider this option.18 In its most liberal form, this could mean free movement to EU citizens with job offers. A more restrictive form could entail a preferential work permit system for EU citizens.19

But the noises coming from the UK Government do not give much cause for optimism. The government has yet to release its much-awaited post-Brexit immigration paper. It was scheduled to be published last summer, but looks unlikely to be released until after the withdrawal agreement has been concluded in the autumn. The best guide to May’s own thinking on the subject (as opposed to those of her Cabinet colleagues) is from a draft Home Office paper leaked last September. The document was uncompromising: an end to freedom of movement after the transition period; preference to resident workers in the job market; a reduction of low-skilled immigrants coming from the EU by offering a maximum residency period of just two years; tighter rules for spousal visas; an end to extended family reunion; and an income threshold for those applying for residency.

Given that Amber Rudd, who is comparatively liberal on migration, is Home Secretary, there is a chance that a preferential migration regime might be forthcoming. Many Brexit-supporting cabinet ministers are more relaxed about the issue than the prime minister.

But there is only so much goodwill that such a migration regime would confer. Officials in Brussels point out that, without EU law in operation in the UK, promises made now by the UK government do not bind the hands of future governments. May has made it a red line that “we can control immigration to Britain from Europe”, and if the UK ultimately chooses a liberal regime, future governments might choose a more restrictive one.

Contributions to the EU’s coffers

Britain’s strongest card in the negotiations has always been its sizeable contribution to the EU budget. Since 2011, its net contribution has averaged £9.6 billion (€10.6 billion) a year, the second largest of any member-state in absolute terms, and the sixth largest in per-capita terms.20

The EU’s budget runs in seven-year cycles, with the current one running from 2014 to 2020. Negotiations over the budget are always fraught, with net contributors fighting to keep spending down (apart from on their priorities); and net recipients fighting to raise it (especially on their priorities). The next budget negotiation promises to be even thornier than usual, thanks to the loss of the UK’s net contribution. Some Central European countries which have had a comparatively good decade, such as the Czech Republic, will see structural and cohesion fund spending diverted to poorer regions in Poland, Romania and Bulgaria, and may join the ranks of the spending hawks. Germany is considering whether to press for the receipt of EU funds to be tied to respect for the rule of law, in an attempt to rein in authoritarian governments in Poland and Hungary. And member-states outside the euro are worried that proposals for a eurozone budget will divert resources from the EU-wide budget.

If May softened her line that the “vast contributions” to the EU must end, would EU member-states be willing to provide levels of access far in excess of the EU’s existing FTAs, without insisting upon freedom of movement?

Rather obviously, €11 billion is a very large sum of money. There is always a disconnect between the political significance of the EU budget and its macroeconomic impact. All nationally-elected politicians will seek to minimise the amount of money they give away to citizens of other member-states, and maximise the amount they receive from other governments. EU spending on investment and agriculture is a significant share of national income in the poorer member-states. This raises the prospect that the UK could persuade Central and Eastern European governments to support UK financial contributions in return for greater market access.

On the other hand, the hole in the budget could be met by member-states that are net payers and those that are net recipients paying more. The simplest way of filling the hole in the budget would be to divide the UK’s net contribution in proportion to the size of each remaining member-state’s economy. This would mean that each member-state would have to contribute 0.1 per cent of GDP more to the EU budget annually, until the UK share of the EU’s current liabilities were paid off. That small figure would not be a macroeconomic problem for any member-state, although for Germany and France, that would entail paying €3 billion and €2 billion more respectively, which would be hard to justify to their voters. Officials in Brussels say that they will probably have to bear down on future expenditure – as well as raising contributions – in order to fill in the hole left by the UK’s departure. Ironically, reforming the budget so that less is spent on farm subsidies may be the least politically costly way of balancing the books (Common Agricultural Policy reform has been a long-standing UK priority).

The next EU budget talks will be thornier than usual: a generous UK contribution might yield some benefits.

Conclusion

The paper has considered four possible reason why the 27 might diverge over their future relationship with the UK. The most likely instigator of a split would be an offer of significant UK contributions to economic development in the poorer regions of the EU. The Polish prime minister said at the Brussels Forum on March 8th that he would welcome UK contributions to the EU budget, post-Brexit.

The politics of the EU budget are going to be especially difficult in the next round, and if the UK offered a significant sum, it might unlock some benefits in the negotiations over a free trade deal.

Any benefits that an offer of money might provide will be limited if the UK does not accept the other obligations of single market membership. The EU’s rights and obligations tend to come as a package. There are good reasons why freedom of movement is the fourth freedom, after goods, services and capital, since people from poorer countries or ones with high unemployment can take advantage of opportunities elsewhere, just as owners of capital in richer countries can invest in poorer ones. EU law provides member-states with confidence that their workers or businesses will not be undercut by countries seeking a competitive advantage. If May’s red lines on the jurisdiction of the ECJ and free movement hold, the best agreement that could be achieved is one that is more like TTIP than EU-Canada.

The 27 have domestic concerns to contend with. In all likelihood the final agreement will need to be voted on by national parliaments. And regulatory issues around standards, the environment and a level playing field weigh more heavily on the continent than the UK might expect. As we have seen with the Walloons holding up the CETA ratification process, any indication that an agreement would undermine the EU social model would lead to problems. While Theresa May has ruled out undercutting EU standards, the EU would insist on enforcement through some legal mechanism. Many member-states will be unwilling to contradict the Franco-German line. France and Germany will be the two greatest contributors to the EU budget after Britain leaves and few Central and East European member-states will be willing to bite the hand that feeds them. It is improbable that any one member-state will want to expend political capital on its own during phase two of the negotiations. And a strong alliance of those opposed to the Franco-German position is unlikely, because the 27 are fragmented in their interests and grievances, and also lack natural leaders. In contrast, the European Commission and European Parliament are united in purpose – they speak with one voice. As it stands, the 27 generally trust Michel Barnier, and reckon that he listens to them.

A stance of complete unity worked in phase one of the talks. The 27 got what they wanted on the sequencing and the withdrawal agreement by acting together. The Commission, Germany and France are in a strong position to persuade the others that continued unity will help them to pursue their interests. And the overwhelming interest among the 27 will remain ensuring the integrity of the single market and the longevity of the European project. And this doesn’t look set to change any time soon, despite Brexit.

2: European Council, ‘Guidelines following the United Kingdom’s notification under Article 50 TEU’, April 29th 2017.

3: Paul Carrel, ‘Merkel open to talks on detail of EU free movement’, Reuters, November 15th 2016.

4: Sophia Besch and Christian Odendahl, ‘Berlin to the rescue? A closer look at Germany’s position on Brexit’, CER policy brief, March 2017.

5: Mark Deen and others, ‘Macron vows decision on bid, warns no Brexit favors for May’, Bloomberg, October 24th 2016.

6: European Council secretariat, ‘Draft guidelines on the future relationship with the UK’, March 7th 2018.

7: Beth Oppenheim, ‘The Ukraine model for Brexit: Is disassociation just like association?, CER insight, February 27th 2018.

8: Wen Chen and others, ‘The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of the Channel’, Papers in Regional Science, December 2017.

9: ‘Brexit: Ireland and the UK in numbers’, Ireland Central Statistics Office, December 2016.

10: European Commission, ‘Draft withdrawal agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community’, February 2018.

11: Philip Hammond and David Davis, ‘A deep and special partnership’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, January 9th 2018. A version in English is available here

12: Michel Barnier, speech to the Centre for European Reform conference on ‘The future of the EU’, November 20th 2017, available here

13: European Council, ‘Guidelines for Brexit negotiations’, April 29th 2017.

14: ‘Bilateral Remittance Estimates for 2016 using Migrant Stocks, Host Country Incomes, and Origin Country Incomes’, World Bank, November 2017.

15: Ruben Atoyan and others, ‘Emigration and its economic impact on eastern Europe’, International Monetary Fund, July 2016.

16: Mateusz Morawiecki, ‘Policy statement by Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, stenographic record’, speech to the Sejm, December 12th 2017.

17: Christian Odendahl and John Springford, ‘The biggest Brexit boon for Germany? Migration’, CER insight, December 11th 2017.

18: ‘The Government’s negotiating objectives: the rights of UK and EU citizens’, House of Commons, Exiting the European Union Select Committee, March 1st 2017.

19: >Joe Owen, ‘Implementing Brexit: Immigration’, Institute for Government, May 2nd 2017.

20: ‘European Union finances 2016’, HM Treasury, February 2017, and Matthew Keep, ‘The UK’s contribution to the EU budget’, House of Commons Library Briefing Paper, February 2nd 2018.

John Springford, deputy director, Centre for European Reform, Sam Lowe, research fellow, Centre for European Reform and Beth Oppenheim, researcher, Centre for European Reform, March 2018

View press release

Comments