Berlin's confounding productivity gap

The bustling German capital scores poorly on a scale of meeting its economic potential. But do its residents care?

Asked which region in Europe has been the absolute worst at realizing its economic potential, most people probably wouldn’t name Berlin. The German capital isn’t just nice to live in, it’s throbbing with excitement; a startup is reportedly created here every 20 minutes, and if you leave for a night out, you risk not coming back for a week. But according to a study of the economic performance of European regions, Berlin is indeed the worst.

The study was conducted by the London-based think tank Centre for European Reform. In a borderless European Union, with the national economies highly integrated, the regional lens is increasingly useful for understanding what’s happening in politics. Younger, more educated people flock to capital cities and build up their increasingly service-based economies. Older, less educated and less affluent people stick around in small towns and rural areas. The average productivity of a capital city worker is about 55 percent higher than that of a small-town one. Accordingly, one sees the capitals voting for progressive parties and the towns and villages often going for nationalist populists. This creates a dilemma for policy makers: Do they try to develop the depressed regions or stimulate the higher-potential people to keep moving to big cities where they can be more productive?

There’s nothing particularly new about those population dynamics or the accompanying dilemma. But the CER’s deep dive into regions’ comparative productivity led to intriguing results. The researchers found that two factors have the biggest effect on a region’s success (read, high productivity per worker): the younger and more educated its population, the higher the productivity. Other factors, such as population density and proximity to other economically dynamic regions, proved far less important.

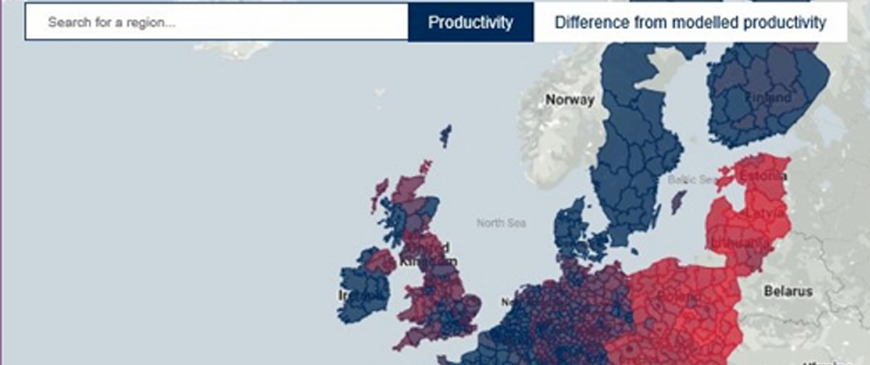

CER then built a model to determine regions’ expected productivity and compare it with actual data. That’s when Berlin emerged as the region with the biggest negative gap between the model’s expectations and reality.

One might question the quality of the model: Most major cities’ actual productivity diverges sharply from its predictions, though it appears to work somewhat better for smaller cities and rural regions. It’s interesting, though, that in some capitals, such as Berlin, but also Rome, Barcelona, Vienna and Madrid, productivity is lower than the youth and education level of its residents would suggest.

All the CER researchers say about this is that Berlin “is a favored destination for young graduates, but has not yet translated that into the higher levels of productivity seen in most capitals in Europe. Many post-industrial towns and cities are not much better: many have not found a niche in an economy that is increasingly dominated by the services sector.” But the German capital has a highly developed service economy: In 2017, according to the city’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry, services accounted for almost 85 percent of its 123 billion euros ($138 billion) of economic output; the average level for German states is 68 percent. Berlin is also a key European creative and tech hub, with tech and media businesses generating about a quarter of the total output.

Christian Odendahl, CER’s Berlin-based chief economist and one of the study’s authors, told me one explanation for Berlin’s (and Vienna’s) underperformance is that Germany (and Austria) are not city-driven economies. Instead, they’re manufacturing-driven, so the most productive regions are more like Volkswagen’s home city of Wolfsburg than like Berlin.

But another possible reason Berlin isn’t as productive as the CER model predicts is that not all young graduates are, or want to be, dynamic, high-producing professionals. There are plenty who do, and they run Berlin’s service economy. But many others — and it’s obvious in Berlin and some of the other productivity-challenged big cities — want to practice noncommercial art or do jobs they believe change the world for the better rather than create a lot of economic value. The preferences, ideas and convictions of young urban Europeans aren’t well-researched, in part because they are a politically passive group. (For example, the under-21 and 21-29 age groups have consistently showed below average voter participation since Germany was refounded after World War II.) It’s conceivable that the relationship between regional productivity and the share of young, well-educated residents is more complex than the CER researchers have allowed.

Some of Europe’s big cities are more conducive to high-octane careers; Frankfurt is Germany’s financial capital, after all. But other cities, like Berlin, may draw a different type of young graduate than the determined soldier of capitalism who will drive up the productivity stats by working for a big tech firm or an investment bank. That probably has political implications, too, but mostly it contributes to a city’s feel, landscape and dominant lifestyle. Berlin, at least for now, has a somewhat bohemian feel to it, with a lot going on that’s not meant to make money — although locals complain that this spirit of voluntary poverty, intellectualism and simple living is disappearing fast.

When I put this to Odendahl, he said he could only speculate on the degree to which particular cities attracted young, educated people who were not career-driven. But, he messaged me, “think about London: at some point, people who are not somewhat career-driven simply cannot afford it anymore.”

Apart from other dilemmas policy makers face when contemplating the sorting of Europeans into the distinct big city and small town castes, here’s one that’s particularly hard to lay out in quantitative terms. What is more important: productivity or a city’s peculiar, esoteric feel? Berlin is one of the places where this question is especially poignant.