Europe needs a strong Africa, but will it work to achieve one?

The massive problems created by COVID-19 in Africa offer Europe a chance to promote a new partnership. But upgrading the relationship will require the EU to confront both illicit financial flows and a looming debt crisis.

The EU has ostensibly been trying to move towards a ‘partnership of equals’ with Africa for decades, but a donor-recipient relationship still largely dictates Europe’s policy towards the continent. COVID-19 has worsened this power asymmetry, as many sub-Saharan African countries face crippling debt and collapsing public infrastructure. But the pandemic also offers an opportunity for Africa to break out of a cycle of indebtedness and aid dependency. Europe should play its part in debt relief and dedicate more resources to curbing illicit financial flows. Doing so could pave the way to a more equal EU-Africa partnership, which European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has made it a strategic priority to achieve.

Europe should seize the opportunity to build a ‘partnership of equals’ – based on trade and investment, rather than development aid and debt.

Africa’s economic development is at a critical juncture: the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which launched its first operational phase in July 2019, commits 54 nations to removing tariffs on goods and liberalising trade in services. If successfully implemented, the AfCFTA may raise GDP and exports substantially. A prosperous Africa would be a valuable export market for the EU. Stronger African economies with a plentiful labour supply could also allow Europe to diversify its supply chains away from Asia, and China, in particular. A wealthier Africa could more easily absorb economic shocks from future crises without recourse to international aid. In the words of EU High Representative Josep Borrell “we need a strong Africa, and Africa needs a strong Europe.”

But Africa will be unable to realise its economic potential without a more robust response to the crisis caused by COVID-19. The pandemic has devastated the economies of many African countries; the World Bank predicts that sub-Saharan Africa will suffer a 3.3 per cent drop in GDP this year. COVID-19 has triggered a crash in commodity prices and a sharp decline in tourism and international remittances; the latter are expected to shrink by 21 per cent in 2020. In February, African finance ministers announced that a $100 billion support package was urgently needed.

While Europe has devoted trillions to healthcare, income support and emergency lending to businesses, many African economies lack the fiscal space to do so, due to the high cost of servicing existing debt. Consequently, many African governments have had to re-route funds towards healthcare, cutting vital investments in education and public infrastructure, which make long-term economic growth even more difficult. Development funding has also been reallocated away from existing programmes towards the response to COVID-19. The European Investment Bank has redirected €300 million that had originally been dedicated to programmes boosting intra-African trade, which were important to Africa’s long-term growth and development.

From early in the pandemic, the EU promised to prioritise Africa and reallocated €15.6 billion from existing programmes to the ‘Team Europe’ global coronavirus response. This includes €12.3 billion to address the socio-economic fallout of the pandemic, around a third of which was allocated to Africa (€2.1 billion for sub-Saharan Africa and €1.2 billion for North African countries). Commission projects include a €60 million package to deliver medical equipment in support of the East African regional organisation Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and sponsoring the African Health Diagnostics Platform, which provided €105 million to improve testing for low-income populations.

EU assistance fills crucial gaps, but many sub-Saharan African governments urgently need more fiscal headroom. To help make this possible, the EU needs to tackle two structural issues: illicit financial flows (IFFs); and mounting debt crises in numerous sub-Saharan African countries. If Africa and Europe are “natural partners”, as von der Leyen claims, EU initiatives in these areas are essential.

Illicit Financial Flows

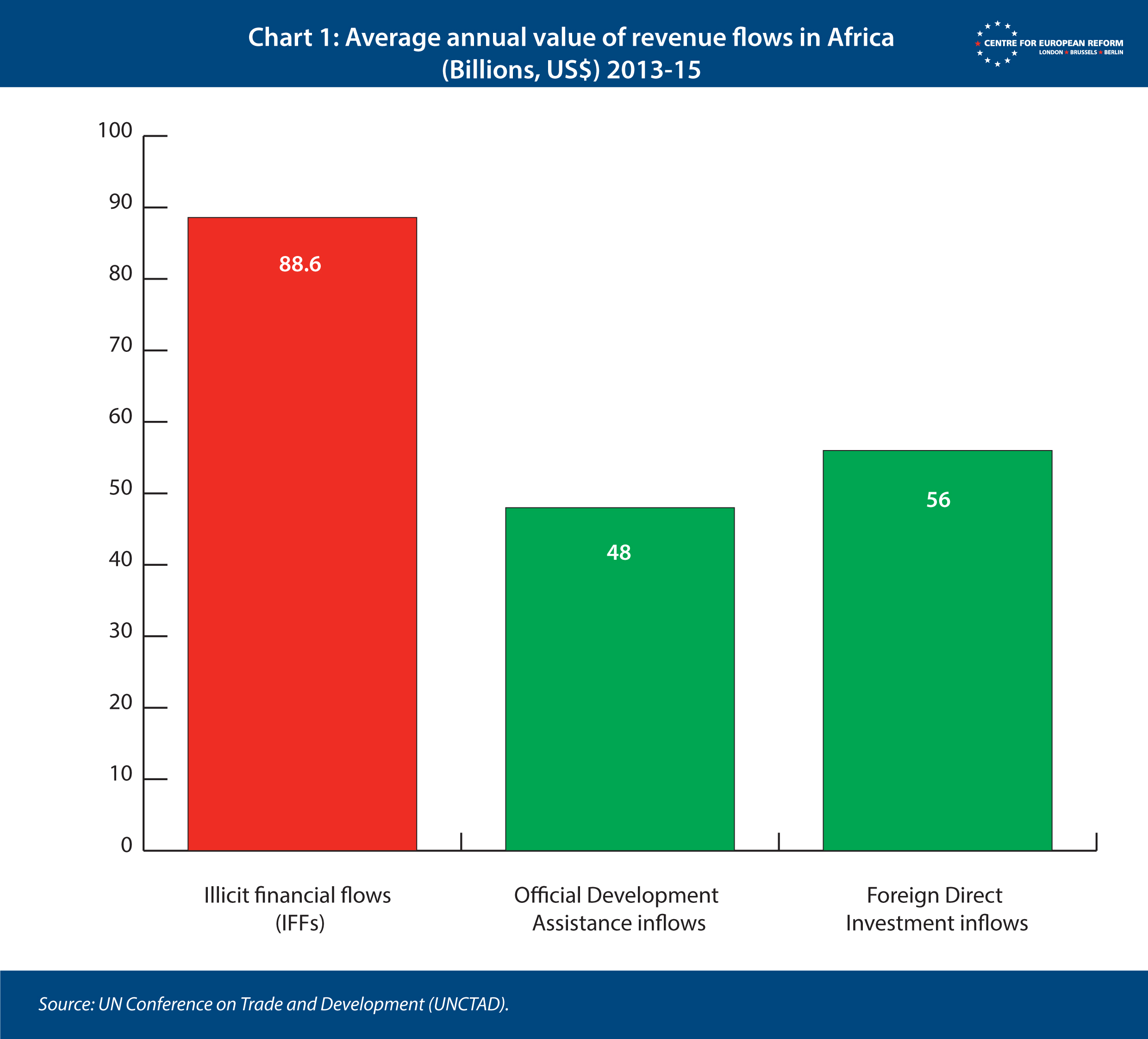

IFFs are defined as the cross-border movement of money and assets that are illegal in their source, transfer or use. IFFs include tax avoidance practices, illegal tax evasion and money laundering. Ending them was a priority for the African Union long before the pandemic. While it is difficult to put an exact figure on the amount of revenue lost through IFFs, there is a general consensus that the number is significant. At the upper end, a recent UNCTAD report found that $88.6 billion per year in revenue is lost by African countries, nearly the combined average yearly value of official overseas development assistance and annual foreign direct investment (see Chart 1). The report found that African countries with high levels of IFFs spend 25 per cent less on health and 58 per cent less on education than countries with low IFFs.

The EU response to IFFs so far has focused on drawing up annual lists of ‘non-co-operative’ countries on tax and money laundering. This approach is unpopular in Africa and elsewhere in the developing world. The Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) States has described it as “unilateral and discriminatory”. The EU’s lists are viewed by some Africans as an attempt to shift the blame to developing countries, despite European countries such as Belgium, Germany, Spain and the UK being among the top 10 destinations for IFFs from Africa. A meagre 0.5 per cent of the money from illicit capital flight is returned to the continent every year.

Europe should make IFFs a sustainable development priority; currently they barely feature in the EU development agenda. First, the EU should advocate the establishment of an inter-governmental forum on IFFs, including both developing and developed countries. Such a forum, which could be facilitated by the UN, could negotiate a new inclusive agreement that fully addresses the problems. Second, the EU should dedicate more resources to international capacity-building projects to counter IFFs, such as the Addis Tax Initiative. This would better equip African governments to audit multinational taxpayers, identify, freeze and recover assets and launch international investigations. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that the Tax Inspectors Without Borders Programme, which supports knowledge-sharing to build the tax audit capacity of developing countries, has added $220 million to tax revenue in Africa from 2013-18; such initiatives must be vastly expanded to recover a fraction of annual loses.

A prosperous Africa could be a valuable export market for the EU. Stronger African economies with a plentiful labour supply could also allow Europe to diversify its supply chains away from Asia, and China, in particular.

Africa’s looming debt crisis

African countries must repay $40 billion in foreign debt in 2020 and up to $50 billion in 2021; in sub-Saharan Africa median government debt-to-GDP levels are forecast to stand at 71 per cent on average by the end of 2020. The G20’s COVID-19 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which postponed debt service payments on official lending to developing countries until December 31st 2020, will provide some relief. The EU should advocate extending the deadline until 2022.

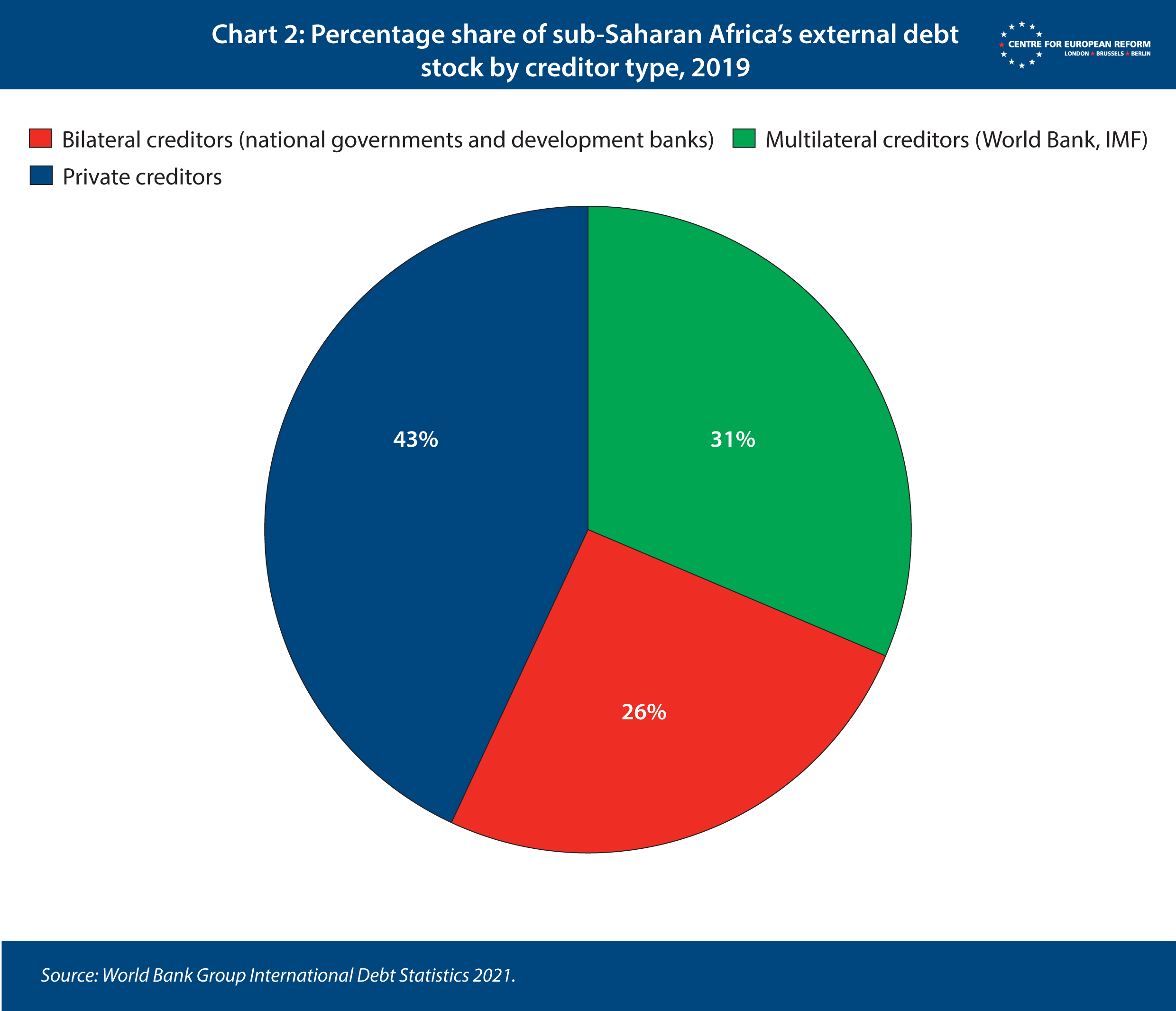

However, newer creditors outside of the multilateral system – China and the private sector – have increasingly dominated lending to sub-Saharan Africa in the past decade (see Chart 2). China has refused to join the DSSI on anything more than an ad hoc, bilateral basis. The private sector has overwhelmingly refused to make any concessions on African debt repayments; the ratings agency Moody’s even downgraded the credit ratings of countries for participating in the DSSI, despite condemnation from the UN. Such downgrades could increase borrowing costs for these countries.

The international refinancing architecture currently centres on the Paris Club, an informal grouping of official (mainly OECD) creditors that seeks solutions when debtor countries have payment problems. Some private lenders have their own club – the London Club – for rescheduling debts to banks, but unlike the Paris Club, the London Club is more reluctant to take proactive measures to refinance debt prior to a default. Europe should start building consensus for a new debt refinancing architecture which includes these newer creditors, putting increased pressure on China and private lenders to join.

Yet debt moratoriums do not always resolve debt crises or foster recovery in the long-term. IMF director Kristalina Georgieva has warned of a “lost generation” and global economic upheaval if tougher action on debt is not taken. IMF research shows that cost of action now could be dwarfed by the cost to global growth, credit and investment should countries (such as Zambia, Angola and Kenya) default on their loans.

The EU should consider more radical solutions. One option may be debt swaps such as ‘debt for development’, whereby creditors cancel debt on condition that the money they release is spent on certain projects. Such swaps both encourage sustainable development and relieve the debt burden, and are typically facilitated by international aid organisations which work with governments to structure implementation plans. In 2017, for instance, the World Food Programme (WFP) negotiated the introduction of a school meals initiative in Mozambique, funded by Russia’s forgiveness of $40 million in loans. The WFP aims to help the Mozambican government gain the capacity to fund and manage the program once the formal debt swap arrangement is over.

The EU should also push for the IMF to issue additional Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to African governments. African countries usually borrow in foreign currencies and must also repay in these currencies. When a currency plunges in value during a crisis, repayments become more expensive and countries are compelled to burn through their foreign currency reserves. In a process similar to quantitative easing, a new SDR allocation would allow these countries access to hard currency to bolster their foreign reserves without being forced into running a current account surplus to pay their debts (which could in turn necessitate spending cuts and tax rises). SDR issuance has been praised for its successes in response to the 2008 recession and has achieved widespread support – including from China – as a response to the pandemic. The US has been blocking action, but a Biden administration could be more receptive, especially if the EU and China jointly advocate it.

Europe should play its part in debt relief and dedicate more resources to curbing illicit financial flows. Doing so could pave the way to a more equal EU-Africa partnership, which European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has made it a strategic priority to achieve.

Alternatively, debt cancellation would directly help African governments increase their public spending and build resilience to future crises. Debt reductions and interest moratoriums can still leave countries with a large debt stock hindering their development, once repayments are resumed. Debt service payments have long prevented African governments from spending enough on public services; more than 30 African countries spent more on servicing debt than on healthcare in 2019.

There is also a strong geostrategic argument for the EU to tackle Africa’s debt distress. Europe faces competition for partnership with Africa from China, which has become Africa’s largest trade partner. However, some African economies are increasingly indebted to Chinese banks, which own around 20 per cent of Africa’s debt. There are growing concerns in several African countries about Chinese ‘debt colonialism’, which China’s reluctance to take part in the DSSI have not assuaged. While China has publicised its forgiveness of official interest-free loans to Africa, these only comprise around 5 per cent of the continent’s total debt to China. Decisive European action could simultaneously undermine China’s credibility on the continent and build trust with African partners.

European initiatives to confront IFFs and debt distress will not automatically build a healthy EU-Africa partnership or stimulate a strong African economic recovery from COVID-19. These measures must be accompanied by others such as increased investment in African infrastructure and the diversification of exports. Intra-continental trade currently accounts for only 17 per cent of African exports compared to 69 per cent in Europe and 59 per cent in Asia. The AfCFTA has the potential help build a strong domestic market, providing a basis on which African economies can diversify. But as part of a recovery effort, tackling IFFs and debt relief are an ideal place to start.

The Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe wrote in ‘Anthills of the Savannah’: “while we do our good works let us not forget that the real solution lies in a world in which charity will have become unnecessary”. Though the COVID-19 pandemic has thrown many African economies into turmoil, Achebe’s world may be closer than it seems. The EU has long been accused of imposing its own priorities on the EU-Africa partnership; the COVID-19 pandemic is a chance for Europe to respond to African priorities, following through on its ambitions for an agreement based on equality in an era where the EU is in need of new friends. Europe should seize the opportunity to build a ‘partnership of equals’ – based on trade and investment, rather than development aid and debt.

Katherine Pye is the Clara Marina O’Donnell fellow (2020-21).

Add new comment