In defence of a bad deal

The EU-US deal will hurt their economies, raise tariffs and weaken the global legal order. But despite it all, the EU was right to accept.

A trade deal is normally the end stage of lengthy negotiations that produce a long list of documents detailing every concession made. In the case of last week’s EU-US trade agreement, there were no such details – only a political agreement with broad guidelines that leave many details unclear or to be negotiated. Moreover, many aspects of the deal are non-binding, or aspirational in nature. Although the agreement will leave everyone worse off in the end, the cost is manageable and preferable to a trade war the EU can ill afford and would likely lose.

Although the EU-US agreement will leave everyone worse off in the end, the cost is manageable and preferable to a trade war the EU can ill afford and would likely lose.

What did the EU get?

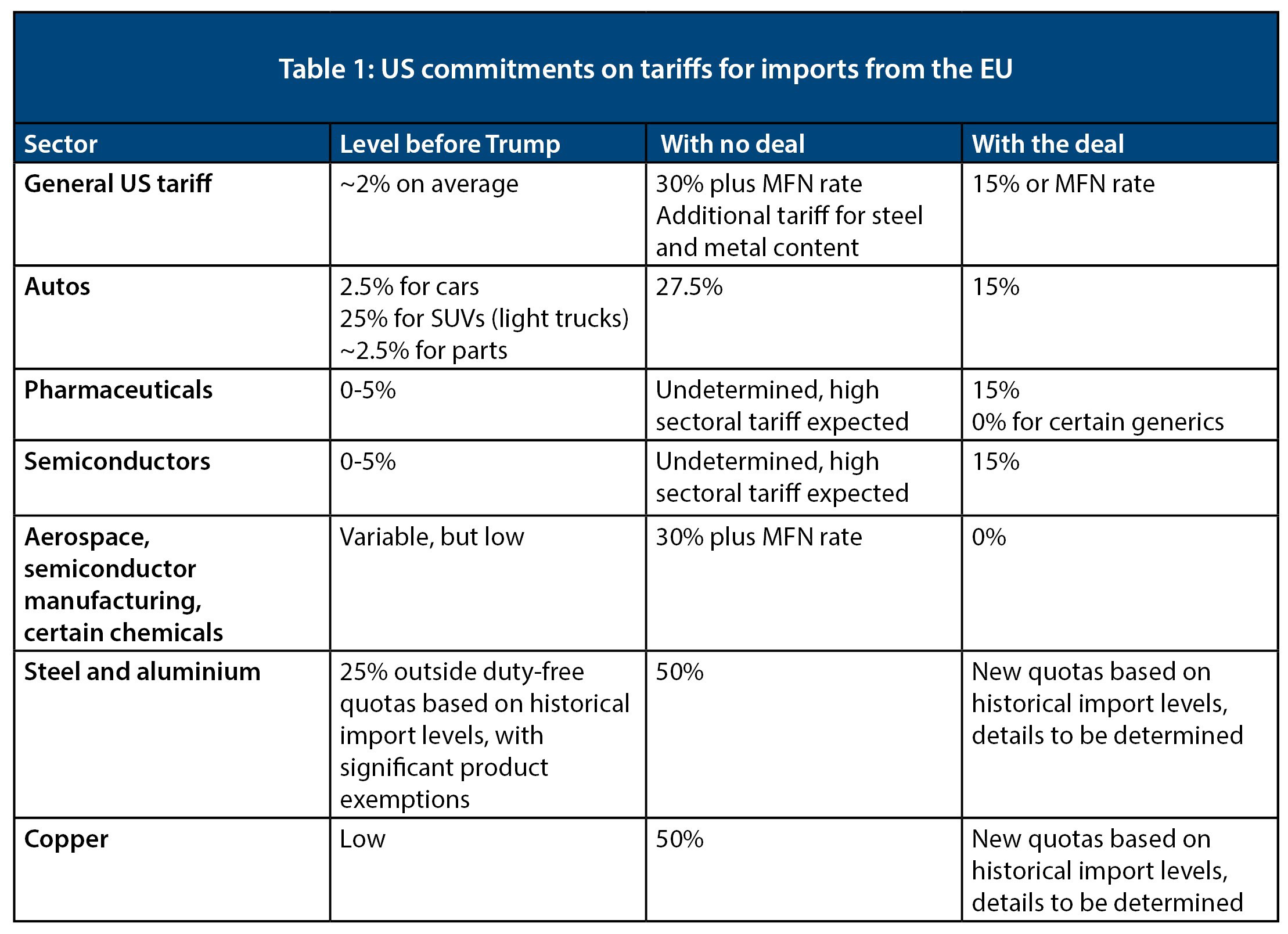

Both sides have an interest in overstating what has been achieved, with the US side particularly prone to this. The wheat must therefore be separated from the chaff in decoding the agreement. On trade, the deal will have a real and immediate impact. Without an agreement, the EU was set to get a tariff level of 30 per cent plus the ordinary, or Most-Favoured Nation (MFN), tariff level in place before Trump. Although MFN tariff rates can go as high as 200 per cent, the average rate for the US is closer to 2 per cent. With the deal, EU products will get a flat 15 per cent except those products where the MFN rate is over 15 per cent, in which case the MFN rate will apply without any extra charge. The 15 per cent rate will also apply to three sectors that, without a trade agreement, would be affected by sector-specific tariffs: autos, pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. For products that have at least 20 per cent US content by value, the US content can be deducted from the value, benefitting products with integrated transatlantic supply chains.

The most significant uncertainty is metals. The US has imposed 50 per cent tariffs on steel, aluminium and copper. For now, these stay in place, but there is a commitment to negotiate tariff rate quotas based on the historical level of imports. This would allow European products to benefit from lower tariffs until exports reach a certain fixed limit, after which they face the full 50 per cent tariff. What is not clear is the size of these quotas, what tariff in-quota imports will face or, crucially, how access to these quotas will be allocated across product categories and to importers. This will be negotiated later on, but could mean a return the situation under Biden, where European steel and aluminium had a similar system in place.

What did the US get?

In return, the EU had to give very significant concessions. The agreement with the US announced last week is the first EU trade deal where the Union actively consents to worse conditions for its exporters. It is also the first EU trade deal made in blatant violation of World Trade Organization (WTO) law – not only because the US is raising its tariffs far beyond the maximum levels allowed in its WTO commitments, but also because both sides will violate the so-called Most-Favoured Nation principle, which requires WTO members to treat all other members the same. The main exemption from this principle is for mutual free trade agreements that liberalise “substantially all the trade between partners”. This agreement, by raising trade barriers, is emphatically not that. For the EU, a creature of international law and dedicated to the rules-based order, this is a bitter pill to swallow.

For the EU, a creature of international law and dedicated to the rules-based order, the US trade deal is a bitter pill to swallow.

Too much can be made of the legal argument, however. There is no WTO police, and WTO rules are only enforceable as long as member-states agree to it, with the only possible sanction being action by other member-states. The US lost faith in the WTO over a decade ago, starting under former president Barack Obama, and there is little other states can do compel it to believe or act otherwise. The proof of this is the long list of other countries seeking deals with the Trump administration, starting with the UK, but also Japan and even China. The EU cannot uphold a global legal order by itself.

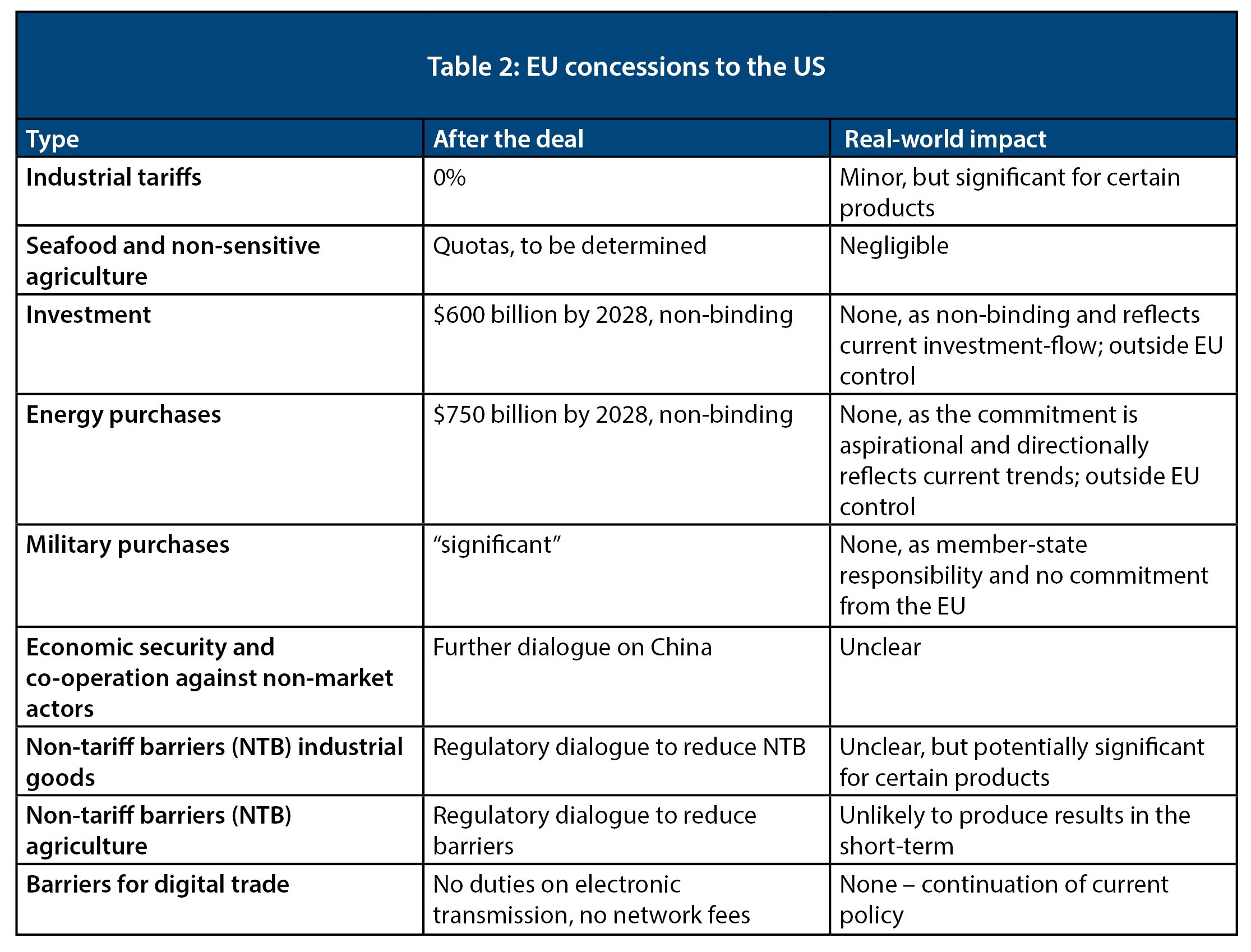

The US has touted $600 billion in increased EU investment in the US as a ‘massive investment’ and asserts that the EU will purchase $750 billion worth of US energy exports by 2028 in addition to ‘significant amounts of military equipment’. None of these claims stand up to scrutiny or constitute binding commitments. The EU does not purchase military equipment – a member-state responsibility – but given increased defence spending, military purchases would increase in any case. The $600 billion investment is merely a continuation of current investment flows into the EU and is in any case non-binding, despite Trump’s public protestations that the EU has agreed to simply hand over $600 billion.

As for the $750 billion worth of energy purchases by 2028, it is both aspirational in nature and nearly impossible in practice as it would require EU imports to nearly triple, and to absorb two-thirds of US energy exports. Even the optimistic projection from the Commission shows that the US would first have to replace the totality of the EU’s energy imports from Russia, and then double its exports to the EU from there. One way to resolve this might be to count the total value of long-term purchasing commitments made in that period. Another way would be to hope for the best and wait for 2028 when a new US administration will be in place, potentially with a different set of priorities.

The EU has also made other concessions. There will be no tariffs on US industrial goods. Most EU industrial tariffs are ‘nuisance tariffs’ – small enough not to affect trade meaningfully, but large enough to provide something that can be bargained away in trade negotiations in return for better market access. This means that the tariff on industrial goods is already zero for countries with which the EU has free trade agreements, and the economic impact of giving the US the same rate will generally be minor. For certain products, however, the difference will be meaningful – a 10 per cent reduction in the tariff on cars imported from the US, for instance. There will also be quotas for certain US seafood and agricultural products deemed non-sensitive.

The rest of the concessions are marked by language pledging to work together, although without any concrete targets. This includes working together to reduce regulatory barriers to trade. In the current context, this could, for instance, make it easier to sell US cars in Europe – although given the significant differences between US and EU petrol prices and European preferences for smaller cars, it seems unlikely that there will be large changes in trade patterns. Particularly as American exporters will be hampered by much higher steel and aluminium prices, due to the 50 per cent tariffs now in place. For agriculture, the EU is unlikely to change its sanitary regulations in any way – on the contrary, the Trump administration is likelier to move closer to EU standards under the influence of US health secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr who has pushed for stricter US standards more akin to the EU approach. In the past, EU-US dialogues on reducing regulatory barriers have taken place with few results, and American exporters should lower their expectations for significant changes in EU policy.

There is also language on co-operation against non-market actors and overcapacity when it comes to steel, aluminium and copper. This is largely code for potential co-ordination of policies against China – but again there are no real commitments. The EU’s targeted and careful WTO-compliant approach to China has been difficult to reconcile with the more antagonistic US approach. But in this area, dialogue by itself is valuable in ensuring that concerns are shared and that the right people on each side know each other, and in fostering possible collaboration and sharing of information. This is particularly true as the EU’s own relationship with China will probably become more conflictual, faced with an unrelenting increase in Chinese exports that threatens key EU industries.

Could the EU have done better?

Some have argued that the EU should have retaliated against Trump’s tariffs. The short-term cost of a trade war would perhaps be worth if it could make Trump back down and save the international legal order and prevent escalating protectionism. But although the EU has a history of trade conflicts with the US, in which it has been able to go toe-to-toe with the US as an equal, these have always been limited in scope: steel tariffs, the Airbus-Boeing dispute and hormones in beef. These limited disputes are all very different from an all-out trade war targeting 1.7 trillion euros worth of annual trade – the world’s largest bilateral trade relationship. Moreover, the US has escalation dominance for three main reasons:

- the US economy is more robust, as it has experienced higher levels of growth over the last two decades and less reliant on trade;

- the US is able to leverage its role as a security guarantor for Europe, making explicit links between the trade relationship and its commitment to European security and Ukraine;

- the current US administration believes, against economic theory and experience, that tariffs will benefit the US economy. This allows the US to engage in far more reckless behaviour than any other nation would entertain, because its government simply does not believe in negative consequences.

As a result, even France, the country with the most aggressive rhetoric, pushed hard for US bourbon to be exempted from retaliatory tariffs when Trump threatened to respond with punitive tariffs on French wine and spirits. Although some EU member-states favoured tough rhetoric, there was never a constituency for a trade war with the US. When the UK and Japan had concluded their deals, and other countries queued up to strike deals of their own, there was no real prospect of the EU confronting the US while at the same time relying on US support for NATO and Ukraine.

Although some EU member-states favoured tough rhetoric, there was never a constituency for a trade war with the US.

Even so, the EU had some leverage and technically skilled negotiators. It alone managed to extract a 15 per cent tariff that acts as a ceiling for most products. For every other country, the new tariffs will come in addition to the MFN tariff. In this respect it got a better than deal than Japan, and for any product with an MFN rate above 5 per cent it also got a better deal than the UK. Tariffs are also a level at which EU car makers can remain competitive. The EU also obtained guarantees for how high any sectoral tariffs on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors can go. Moreover, the EU also has two clear outright winners in ASML and Airbus, which will now face zero tariffs. Particularly for Airbus, long embroiled in transatlantic trade disputes, this is a refreshing change.

In trade, it is not just the absolute level of tariffs that matter – it is also how high they are compared to your competitors. The EU has secured a deal that gives it preferential terms equivalent to or better than those of the US’s FTA partners like Korea, Australia and Israel –at least now that these countries also face higher tariffs. It also means that the EU will face much lower tariffs than China for instance, giving it a competitive advantage, mitigating the damage. An example of how this could play out is from Trump’s first term: when the US first put in place steel tariffs under Trump’s first term, the amount of steel exported from the EU to the US went down from about 4.5 million tonnes a year to 3.3 million. But the value went up by 31 per cent from 2018 to 2022 because of the increased price level in the US, compared to a 10 per cent increase for non-US exports. The negative effect on exports was mitigated by higher prices as European steel manufacturers could largely export duty-free through quotas and exemptions. Similarly, this agreement may increase tariffs, but since the tariffs on EU goods will still be lower than for goods from most other places, it will make European exports more competitive compared to Asian countries in particular. One estimate puts the overall impact on EU GDP at a very manageable -0.13 per cent of GDP – far better than the alternative of a trade war and better than the estimated impact of -0.36 per cent on US GDP.

Europe no longer has the legal certainty it grew accustomed to with the US – instead, the relationship will require constant management and adjustment, with the accompanying risk of conflict.

It is tempting to say that the EU should not have made a deal, as the Trump administration cannot be trusted and might come back with more demands. And the deal could still fall through as details are being clarified. But this deal does not depend on trust – the EU retains the option to retaliate if either the deal falls through or Trump comes back with fresh demands. The logic of this argument would be to not make any deal at all – but the two sides of the world’s most important trade relationship have a duty to try. Europe no longer has the legal certainty it grew accustomed to – instead, the relationship will require constant management and adjustment, with the accompanying risk of conflict. In the end, that is also the best defence of the deal. In a time where everything is falling apart, the EU is right to hold on to whatever it can get.

Aslak Berg is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment