European strategic autonomy and a new transatlantic bargain

- The EU has been trying to develop its capacity for independent military action since the launch of its Common Security and Defence Policy in the late 1990s. But the EU’s efforts gained significant momentum with Donald Trump’s presidency, which fuelled concerns that the US was no longer a reliable ally. In response, the EU launched a set of defence initiatives, focused on improving its military capabilities.

- European ‘strategic autonomy’ emerged as an umbrella concept for these efforts to turn Europe into a more capable security and defence actor. But member-states were divided on whether strategic autonomy was desirable, with many concerned that it would undermine NATO by duplicating its efforts and annoying the US. The Trump administration also opposed the EU’s efforts.

- With Joe Biden’s election as US President, many Europeans will want to forget Trump’s presidency ever happened, and may row back on their efforts to develop EU strategic autonomy. But Europeans should not be tempted to act as if Trump’s presidency never occurred. Trumpism is likely to endure, and Europeans cannot be sure whether the president after Biden will be committed to European security.

- Europeans do not need to choose between pursuing their security through the EU, or through NATO and the alliance with the US, nor should they. Instead of debating strategic autonomy, Europeans should focus their efforts on concrete steps that would improve their security and defence capabilities, and help them to develop a common strategic outlook. This will ensure they are better able to protect their interests, whether acting together with the US, through the EU or through other frameworks.

- A more capable Europe will probably mean a degree of European divergence from the US, especially in industrial matters, including fewer purchases of American arms. But this should be a price that is worth paying for Washington: a more capable Europe would lighten the burden on the US and provide the basis for a renewed transatlantic security partnership.

European leaders greeted Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential election with relief. Unlike his predecessor, Donald Trump, Biden does not want to undermine the EU, and believes in the value of NATO and the principle of multilateralism. He will recommit the US to European security, ease transatlantic tensions, and make it possible for Europe and the US to forge a common transatlantic approach to many of the common challenges they face.

Many Europeans will want to forget Trump’s presidency ever happened, and in the Biden era they may row back on their efforts to develop EU ‘strategic autonomy’ in security and defence. The EU has been trying to develop its capacity for independent military action since the launch of its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) in the late 1990s. But in its latest incarnation, strategic autonomy is French President Emmanuel Macron’s brainchild. The term has been used to describe Europeans’ efforts over the past four years to develop their capacity to carry out military operations without US support, and develop more arms together at home rather than buying them abroad. The subject has already received renewed attention with the US election. German Defence Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer argued that Europeans should abandon “illusions” of European strategic autonomy since they would not be able to replace America as a security provider, echoing arguments that leaders of Central and Eastern European member-states have often made in recent years.1 Other politicians, like Macron and EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell, have argued that Europeans cannot be sure of America’s reliability and that Biden’s victory should not distract them from efforts to advance their strategic autonomy.

Europe cannot continue to look to the US to answer key questions on what its interests are and how it should pursue them.

However, the distinction between a ‘European path’ and a ‘transatlantic path’ in EU defence is misguided, and the supposed disagreement between Berlin and Paris feeds a straw man debate. Europe needs to become a more capable security and defence actor, both to work better with the United States, and because it will have to go it alone if its interests are not aligned with the US. While the Biden administration will probably be more supportive of EU defence efforts than the Trump administration has been, it cannot be expected to hold Europeans’ hands through another four years of debating strategic autonomy. Europe cannot continue to look to the US to answer key questions on what its interests are and how it should pursue them. Instead, European governments should take advantage of the fact that there is no longer the distraction of an adversarial transatlantic relationship, and invest both financial and political capital into strengthening their ability to carry out military operations, whether through the EU, NATO, or other frameworks. And the ability to act is not enough: Europeans will also need to summon up the will to act effectively.

This policy brief takes stock of the EU’s strategic autonomy debate, assessing the US’s role in European defence, the EU’s defence efforts over the past few years and European governments’ disagreements with the Trump administration in this area. It then sets out Biden’s expected approach when he takes office, and sketches out a framework for a new transatlantic bargain that would lead to fairer burden sharing between Europe and the US. It argues that Europeans should fill the gaps in their defence capabilities, and invest in developing a shared strategic outlook, both for their own sake and to put the transatlantic alliance on a fairer and more solid footing for the future.

The US and Europe’s security

For decades, the US has invested heavily in European security. American troops, tactical nuclear weapons and missile defence systems are stationed across the European continent, and the US military trains with European troops through NATO and other frameworks. Europeans depend on the US for their security. A study conducted in 2019 by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) found that, in order to defend NATO’s eastern flank against an attack by Russia, Europeans would have to invest between $288 billion and $357 billion to fill the gaps left by a US withdrawal.2

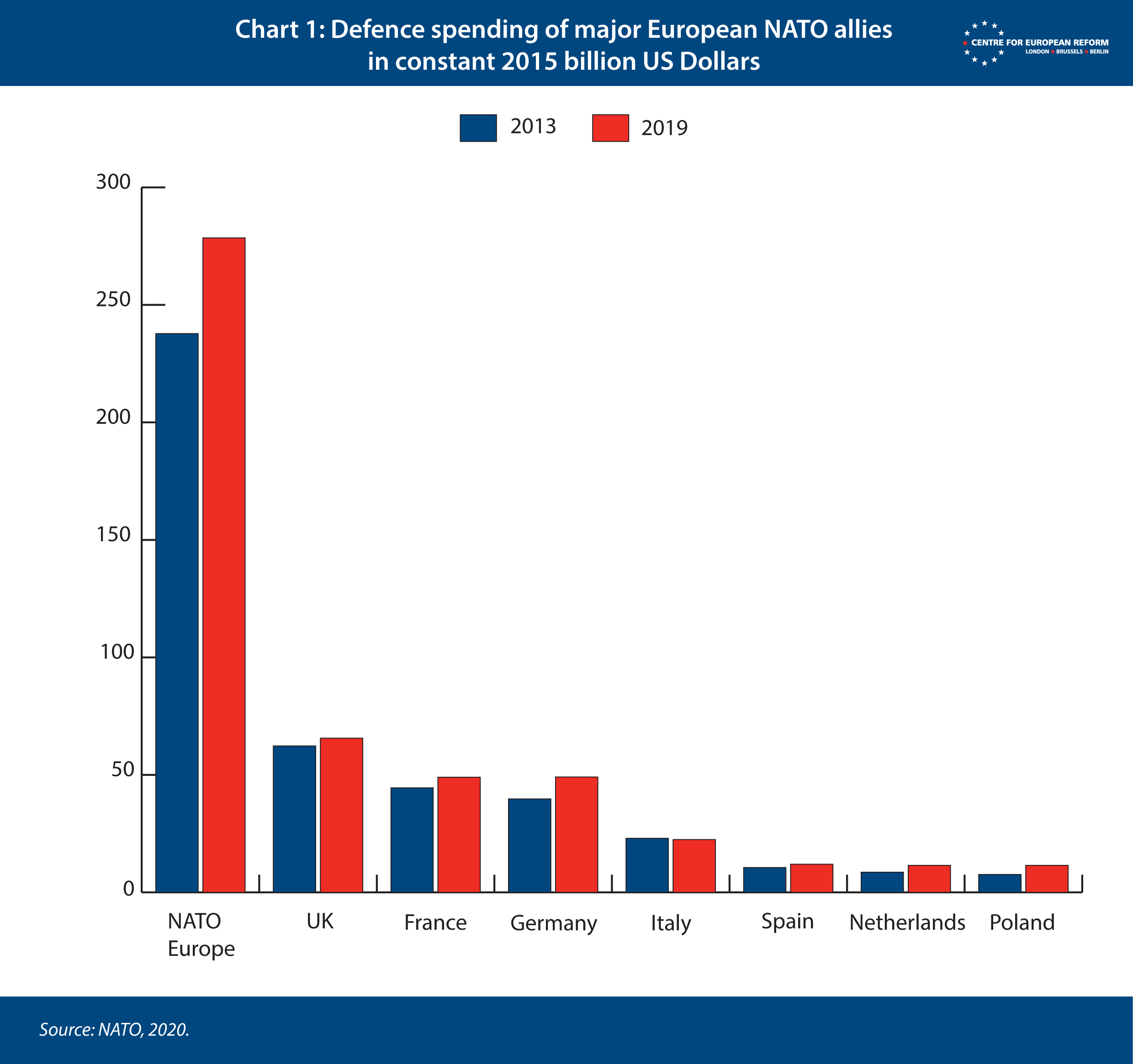

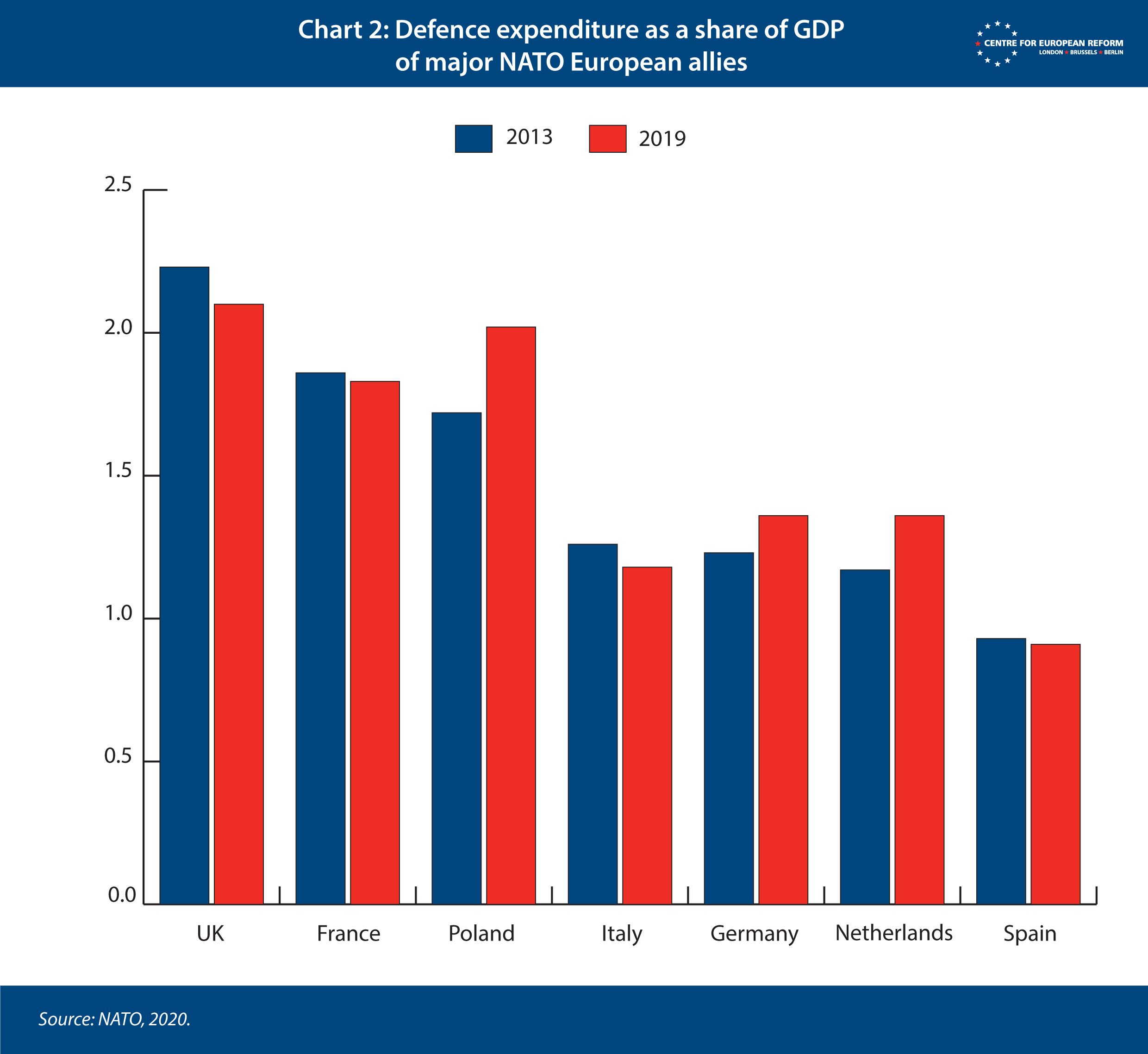

Donald Trump’s presidency undermined European security. Under Trump, the US adopted a much more negative stance towards NATO, EU defence efforts and the EU in general. Previous US presidents had urged European NATO allies to meet the Alliance’s target of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence. Trump applied unprecedented pressure to that end, unjustly accusing allies of owing the US or NATO huge sums of money, while casting doubt on whether the US would defend its allies if they came under attack. Trump also decided to reduce the number of US military personnel stationed in Europe, particularly in Germany, ordering the withdrawal of 12,000 troops (but redistributing nearly half of those withdrawn to other European countries, especially Italy and Belgium).

Spurred on by Trump’s urgings and worries about the conflicts in Europe’s neighbourhood, many member-states made progress towards meeting the 2 per cent goal. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) found that in 2019, military expenditure in Central Europe was 61 per cent higher in real terms than in 2010. Germany, often singled out as an economic giant but military dwarf, spent more on defence in 2019 than at any point since 1993, and 15 per cent more than in 2010. However, defence spending in Western Europe as a whole remains 0.6 per cent lower than in 2010.3 Trump’s criticisms of NATO also prompted the allies to agree on a new funding arrangement for the alliance’s budget, albeit a largely symbolic change when compared with overall national defence spending. In 2019, the US paid around 22 per cent of NATO’s running costs (with Germany contributing just under 15 per cent and France and the UK around 10 per cent each), but under the new plan, the US contribution would drop to 16 per cent by 2024.4

Towards European ‘strategic autonomy’

Trump’s attacks on the EU, his withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and his equivocal stance on NATO, as well as conflicts in Europe’s neighbourhood, gave impetus to the EU’s effort to increase its own defence capabilities. Member-states were also galvanised by the UK’s decision to leave the EU, which removed the UK’s veto on deepening European defence.

The EU’s defence efforts have focused largely on bolstering Europe’s defence industrial base and improving capabilities.

The EU’s defence efforts have focused largely on bolstering Europe’s defence industrial base and improving capabilities. In 2017, 25 member-states launched Permanent Structured Co-operation (PESCO), a co-operation framework under which they have pledged, for example, to raise defence spending, improve the readiness of their armed forces and work together on capability projects. The EU’s Co-ordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD), launched in 2017, is designed to co-ordinate member-states’ investments in filling the capability shortfalls European militaries struggle with. With the new Multiannual Financial Framework, the European Commission will launch a European Defence Fund (EDF), worth €7 billion over the 2021-2027 period, to finance joint research and procurement projects, and it has set up a Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space to oversee defence industrial efforts. At the same time the EU will also invest €1.5 billion in improving military mobility, by investing in infrastructure projects to make it easier for forces to cross borders. Finally, member-states are currently in negotiations over a European Peace Facility, designed to help them finance joint operations and allow the Union to provide weapons for foreign militaries.

Though the EU’s defence initiatives have been dominated by efforts to fill capability gaps, Europeans have also sought to enhance their ability to deploy together if necessary. In recent years, the importance of military operations conducted under CSDP has decreased; instead, member-states prefer to act through coalitions of the willing. Realistically, not all member-states will be able or willing to intervene militarily to address a crisis. But often, they do not even agree on the most important security challenges or on how to tackle them. With this in mind, French President Emmanuel Macron set up the European Intervention Initiative (EI2), outside the Union’s framework. The EI2 encourages its 12 members, including the UK, to discuss threat assessments and exchange expertise and intelligence. The aim is to foster a common European strategic outlook, which would make it easier to deploy together in the future, whether through NATO, the EU, the UN or in an ad hoc ‘coalition of the willing’. Under the German EU Presidency, the Union has also launched a ‘Strategic Compass’ process, with the aim of fostering a shared understanding of threats facing the EU and how to respond to them. The Germans hope to counter the trend of undertaking operations outside the EU framework. Member-states have until the French EU Presidency in 2022 to agree on what role they envisage for the EU in security and defence.

Strategic autonomy implies that Europeans share an understanding of their common interests and the threats facing them.

European strategic autonomy emerged as an umbrella concept for these efforts to turn Europe into a more capable security and defence actor. The concept of strategic autonomy is not new. The idea has been around since Europe failed to intervene in the Balkan conflicts on its own in the 1990s. The desire to be able to act autonomously was one of the driving forces behind the establishment of CSDP in the late 1990s. Nevertheless, the meaning of the term remains ambiguous. In the traditional sense, used in this policy brief, strategic autonomy refers only to security and defence, and denotes Europe’s ability to act without the US or NATO if necessary. Being strategically autonomous in this sense means that the EU should have an industrial base that produces the capabilities it needs to act alone, as well as the necessary political decision-making and military command structures, and also that national armed forces should be trained and equipped to deploy together. In addition, strategic autonomy implies that Europeans share an understanding of their common interests and the threats facing them. But the concept of strategic autonomy has also been applied beyond the realm of security policy, to the economic field. Its precise meaning is disputed here, too. For some, particularly in Northern Europe, it denotes the EU’s power to shape global rules and a level playing field. For others, like European Commissioner for the Internal Market Thierry Breton, it refers to the power to foster more globally competitive European companies and even re-shore certain industries that are deemed of critical importance.

The EU Global Strategy of 2016 affirmed the Union’s ambition to be an independent actor in security and defence. The strategy explains: “While NATO exists to defend its members – most of which are European – from external attack, Europeans must be better equipped, trained and organised to contribute decisively to such collective efforts, as well as to act autonomously if and when necessary.” In November 2016, member-states agreed on three high-level priorities: preventing and managing crises in the EU's neighbourhood; building up partners’ capabilities; and protecting the EU and European citizens. However, member-states remain divided about what these priorities entail. Their different strategic outlooks and lack of capabilities make it difficult for the EU to manage crises in its neighbourhood on its own. States also disagree over whether the EU should have a role in territorial defence. Most member-states see that as NATO’s task, but Article 42.7 of the Treaty on European Union commits member-states to assist each other if they come under attack. Four years after the adoption of the Global Strategy, member-states are even divided on whether strategic autonomy is desirable. Under Macron, France has strongly pushed for greater autonomy, while many eastern member-states remain sceptical, concerned that it would undermine NATO by duplicating its efforts and annoying the US.

US opposition to EU strategic autonomy under Trump

The US has always had an ambiguous attitude towards the EU’s efforts to become a more capable defence actor. Traditionally, Washington has encouraged Europeans to take on greater responsibilities for their own security. At the same time however, the US has always seen NATO as the primary framework for Europe’s defence. In 1998, US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright stated the US was in favour of EU defence initiatives, as long as they did not result in de-linking from NATO, they avoided duplicating existing efforts, and they did not discriminate against non-EU members of NATO. This stance more or less persisted under subsequent US administrations.

From this perspective, officials in the Trump administration were concerned that European strategic autonomy might signal that the EU could increasingly go its own way rather than follow the US lead, as it did (without much success) by trying to preserve the Iran nuclear agreement after Trump withdrew from it. At the same time, talk by European politicians of a ‘European army’ fuelled US concerns that EU initiatives were unrealistic and would divert precious resources from NATO and hinder allies from meeting their pledge to spend 2 per cent of GDP on defence. These US concerns persisted, despite the EU’s unprecedented efforts to deepen co-operation with NATO. Many in the US saw the debate about strategic autonomy as distracting from the real issue of how Europeans could improve their capabilities.

Trump’s administration, however, also had a more practical set of concerns. Washington thought that PESCO and the EDF might lead to the European defence market becoming less open to US companies. The EU’s Defence Fund does not exclude co-operation between EU-based defence companies and US firms on EU-funded projects. However, its eligibility rules stipulate that third-country firms cannot have access to sensitive information, own intellectual property funded by the EU or transfer it outside the Union. These conditions make participation in EDF-funded projects unappealing for third-country firms. In this context, the US was critical of the slate of EU defence initiatives launched since 2016. In May 2019, senior US officials wrote a letter to the EU in which they branded the EU’s Defence Fund and PESCO as “poison pills” for the transatlantic relationship.5

Strategic autonomy has remained a source of both transatlantic and intra-European disagreement.

EU officials argue that with its defence industrial initiatives, the Union is merely pursuing reciprocity, and that their conditions for receiving funding are in fact more lenient than those that EU companies face in the US. They point to the American International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which ban the export of defence-related data, technology or knowledge from the US without a licence, under penalty of fines or imprisonment. The US also applies ITAR outside its own territory, meaning it can be used to stop transfers between two EU countries of weapon systems that contain protected intellectual property – a further incentive for Europeans to develop their own systems. US officials have nevertheless criticised the EU’s rules on third-country access, not only condemning the fact that US firms would miss out on European business, but warning that if Europeans were limited to just their own market they would miss out on new technologies and lose interoperability with American forces. Additionally, some EU governments defended Washington’s case: Central and Eastern European states feared undermining NATO, while Nordic countries with defence industry links to the US suspected EU initiatives were about helping Western European (especially French) defence firms win a bigger market share rather than turning the EU into a more capable defence actor.

Europeans have so far failed in their efforts to convince Washington that strategic autonomy would mean a more capable Europe, better equipped to shoulder the burden of European security together with the US. This failure, combined with some Europeans' unwillingness to meet NATO's target of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence, means that strategic autonomy has remained a source of both transatlantic and intra-European disagreement. US opposition and the scepticism of many member-states have also hindered the further development of the EU’s defence initiatives.

Biden’s approach to defence and security affairs

Biden’s presidency will lead to an easing of transatlantic tensions in a range of policy areas, from climate change and trade to defence and security. The difference with Trump is likely to be especially stark in the defence and security field, as Biden is a committed Atlanticist who believes that NATO serves US interests. Once in office, he is likely to dispel doubts about the US’s commitment to NATO and to Europe’s defence, strengthening deterrence. Biden may also review some of Trump’s cuts to the US troop presence in Europe, including the planned withdrawal of US troops from Germany. Biden’s commitment to arms control will also benefit European security. He is likely to extend the New Start agreement with Russia, which limits numbers of nuclear weapons. He has also stated that he intends to re-join the nuclear deal with Iran if Tehran resumes full compliance with its terms, which would make a conflict in the Middle East less likely.

All this is excellent news for Europeans. Tensions will ease and transatlantic debates over defence will become much more civil. However, transatlantic differences over burden sharing will not disappear. Like Obama, Trump and every American president since the 1960s, Biden thinks that Europeans should invest more in their own defence. While the Biden administration might be more open to the new EU defence industry policies, Europeans have yet to demonstrate that their efforts will actually create a stronger partner for the United States, rather than just help European defence industries win market share from American firms. The US will always look at Europe as both an ally and a potential buyer of arms. If Europeans cannot persuade Washington that EU defence initiatives will lead to concrete improvements in their capabilities, the Biden administration is likely to push them to do more, and to enhance their capabilities by buying US equipment.

Moreover, Biden’s presidency will not alter the structural shift in US foreign policy priorities away from Europe and the Middle East and towards China and the Pacific, which began under Obama and continued under Trump. The threat posed to US interests and the security of American allies in Asia by a rising China has led to a bipartisan shift in perceptions of the main threat to US interests. Democrats do not talk about China in the same crude terms as Trump, but they still perceive China’s rise as a threat. Biden has said he considers China “the greatest strategic challenge to the United States and our allies in Asia and in Europe”.6 The US will be increasingly focused on countering China’s rise and deterring Beijing from asserting itself militarily in the South and East China Seas and elsewhere. Today the largest numbers of US troops overseas are deployed in Japan, with many also stationed in South Korea. Biden has also committed to reducing the US presence in the Middle East. In the future, the US will probably focus on supporting local allies with small numbers of troops and use drones and special forces for small-scale counter-terrorism operations.

European security will be profoundly affected by this re-orientation of US attention away from Europe and its expanded neighbourhood. In the future, Europeans are likely to be less and less able to count on the US to take the lead in tackling conflicts that directly impact on Europe’s security, but fall below the threshold for NATO’s Article 5 mutual defence guarantee to be invoked. Biden may be willing to support European-led operations ‘from behind’, providing them with capabilities that they lack, such as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft and air-to-air refuelling. But the assumption in the White House is likely to be that Europeans should be primarily responsible for addressing crises in their own neighbourhood. This means that the US is unlikely to take on a major role in ending Libya’s civil war, in stabilising Syria, or in supporting Iraq. And a future US president in the mould of Trump might leave Europeans wholly alone, unless a crisis emerges that directly threatens US interests.

Towards a new transatlantic balance

Europeans and Americans face a formidable set of shared challenges, ranging from fighting the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change to countering authoritarian rivals like China and Russia, upholding human rights and nurturing democracy across the world.

Europeans need to take on more responsibility for their own security, not because the US is asking them to do so, but because it is in their own interests. The bipartisan consensus in the US on countering Chinese influence and limiting military involvement in the Middle East means that future US administrations are likely to continue to shift their focus away from Europe and its neighbourhood. The US will probably continue to ensure conventional and nuclear deterrence against Russia, and possibly support European military operations with capabilities they lack, should Europeans decide to intervene in a conflict. However, Washington’s priorities in Europe’s neighbourhood may not always be the same as Europe’s, especially in the Middle East and North Africa. Europeans will need to be ready to do more for their own security.

The pandemic may lead to yet more cuts in defence spending, meaning that there is a risk Europeans will be tempted to focus on continuing to debate abstract concepts like strategic autonomy rather than investing resources in improving their ability to act on their own. But they should avoid the temptation to do so. Focusing on delivering concrete outcomes is less likely to be divisive within Europe and will also be better received by the US.

More broadly, Biden’s presidency presents Europeans and the US with an opportunity to both share the security burden more fairly and overcome the toxicity of the burden sharing conversation. European security involves a much broader set of issues than whether every country spends 2 per cent of GDP on defence, or the precise number of US troops and assets that are based in Europe. Burden sharing encompasses readiness and training, arms control arrangements, investments in military mobility across Europe and the ability to counter hybrid threats and terrorism. It also encompasses efforts to stabilise countries in Europe’s neighbourhood, for example by giving financial assistance, providing local security forces with equipment and training, or reforming governance structures to fight corruption and promote accountability. Even NATO has repeatedly tried to refocus the burden sharing debate on a wider set of indicators than just the 2 per cent target. For example, its members have pledged that by 2024 at least 20 per cent of their defence expenditure should go into acquiring and developing new equipment. If over the next four years both sides could broaden their understanding of burden sharing beyond the 2 per cent, more constructive and less divisive exchanges could ensue.

The key ingredient in a new transatlantic division of labour would be a more capable – and willing – Europe. Europeans would invest more in their own defence and take on more responsibility in dealing with shared transatlantic challenges. They would become able to handle crises in Europe’s neighbourhood either by themselves, or with very little US support. They would take the lead whenever military action might be necessary, for example to separate fighting parties and secure a ceasefire, or to provide military support to regional allies. For its part, the US would continue to provide nuclear and conventional deterrence against Russia in Europe, but would be otherwise free to shift its focus gradually away its focus away from Europe and its neighbourhood and towards the Asia-Pacific.

Recommendations for Europeans

Europeans need to focus on becoming more capable defence actors, whether through the EU, NATO or other formats. To do so they should:

1) Focus on improving Europe’s capacity to act rather than on abstract debates.

They should avoid getting bogged down with unhelpful rhetoric, starting with references to setting up a European Army, something that not even most of its proponents actually want. The whole debate surrounding European strategic autonomy in security and defence has also been divisive and risks distracting Europeans from the more concrete task of how to improve their ability to act. For some member-states, this may not be a problem: as long as Europeans are discussing abstract concepts, they can avoid investing political and financial capital in defence. Proponents of strategic autonomy should shift their emphasis to advancing a more concrete debate about threats and capabilities. This would help persuade both European sceptics of strategic autonomy and the US of the merits of a stronger EU in security and defence. A starting point to convince sceptics could be investing seriously in aligning NATO and EU defence efforts, notably in ensuring that NATO’s planning process and the EU’s new co-ordinated annual defence review are fully joined up.

Proponents of strategic autonomy should shift their emphasis to advancing a more concrete debate about threats and capabilities.

2) Ensure that EU initiatives deliver.

The economic shock of the pandemic means that national defence spending may fall in many member-states. After the financial crisis of 2007-2008, European governments cut defence budgets, reducing spending especially on research and capability development. And, instead of co-ordinating cuts, governments prioritised national over European security of supply. These cuts had lasting effects across the EU. While budgets have slowly recovered in recent years, capability gaps remain. If they had sufficient resources, PESCO, the EDF and CARD could contribute to preventing a similar dynamic today, safeguarding European capabilities, technologies and skills. But the funding for these initiatives has been reduced substantially in the EU’s 2021-2027 budget, compared to the European Commission’s original proposals, calling into question their potential to change European defence.7 By not allocating enough money, member-states are setting PESCO and the EDF up to underperform.

In November 2020, the EU published its first CARD report and PESCO review. They assess the performance of the EU’s defence initiatives and how they fit in with member-states’ defence efforts. They paint a grim picture: the CARD report points out that the EU’s initiatives “have yet to produce a significant and positive impact on the European defence landscape”. Looking specifically at capabilities, it shows that national approaches to capability development continue to prevail and the outlook for defence research and technology spending continues to be bleak. Meanwhile, the PESCO review shows that member-states have often used the framework to get financial support for pre-existing multinational projects rather than launching new projects to fill identified capability gaps. The review is also pessimistic on the question of whether member-states are willing to deploy military forces, finding that they only contribute small numbers of troops to EU operations.

To ensure the success of EU defence initiatives, member-states will have to give them a greater sense of direction. Take PESCO: some governments joined largely in order to ensure that it did not undermine NATO, or fearing exclusion from a close-knit core group of EU member-states. The CARD review identified six areas as priorities for the joint development of new capabilities: main battle tanks; individual protection and awareness systems for soldiers; patrol ships; countering aerial threats; military mobility; and space-based assets. These projects do not address Europe’s main capability shortfalls and even if implemented, they would not be a game-changer. But at least if member-states agree to prioritise them, the EU can add some value. In general, it will be difficult for the Union to break into the field of defence planning. Member-states prefer pursuing big capability projects in small intergovernmental groupings. And their defence spending plans for the next five years have been decided: the EU can only hope to influence capability planning after 2025.

The hope is that by that time, the Strategic Compass can provide guidance, both for joint capability development and joint EU military operations. The EU should work closely with NATO, to align the process of writing the Compass with the process of writing NATO’s new strategic concept, which is going on in parallel. This is a unique opportunity to work out a concrete burden sharing agreement between the two organisations. Otherwise, the risk is that the Compass will become yet another well-meaning reframing of European defence ambitions, with member-states agreeing to do more on paper but failing to take action.

Improved capabilities alone will not make Europe a more effective security actor.

Europeans should also recognise that they face a trade-off between greater defence industrial autonomy and more developed capabilities. If they want to be less reliant on US firms and strengthen their own defence base, to avoid being affected by US export restrictions or depending on American companies for critical spare parts, they will find it harder to build up their capabilities to intervene swiftly and decisively when required. Building up the European defence industrial base will not be easy, because developing new kit takes time to design and manufacture. Conversely, if Europeans emphasise access to capabilities at the expense of autonomy, they may find that they end up buying more high-end equipment from US firms, and their defence base will atrophy.

3) Focus on improving readiness and willingness to act.

EU defence initiatives can contribute to generating the military capabilities that Europeans need, and can also help them agree on a shared assessment of the threats facing the EU and how to counter them together. However, ensuring the success of European defence initiatives is only one part of what Europe has to do to take on more responsibility for its own security. Europeans will have to invest more in the readiness of their armed forces, and their ability to move. Many of these efforts will happen through NATO. Beyond investing in conventional defence capabilities, Europeans will also have to invest more into emerging civilian technologies with military applications, such as quantum computing or artificial intelligence, not least to assure that their military forces remain fully interoperable with the US military. Europeans will also have to increase their preparedness to counter ‘hybrid’ challenges such as disinformation campaigns, particularly from Russia and China, and cyber threats by government-sponsored hackers and other groups.

Improved capabilities alone will not make Europe a more effective security actor. If they actually plan to deploy troops together, Europeans will have to continue to focus on developing a common strategic culture and streamlining decision-making. Initiatives like the Strategic Compass, the French-led EI2 and possibly a ‘European Security Council’ can all help member-states to agree more easily on how to address foreign policy challenges. The EI2 and a European Security Council could also help to keep the UK plugged into some of the thinking around European foreign and security policy. In addition, in order to reduce obstacles to deploying together in the EU, member-states could activate treaty provisions that permit the Council to task a group of member-states with implementing a military operation on the EU’s behalf.

Recommendations for the US

For the US there is a choice between having weak allies that are highly dependent on it, or encouraging Europeans to stand on their own feet. Without transatlantic co-operation, even if each member-state raised defence spending to 2 per cent of GDP, most member-states would still be left with what are often called ‘bonsai armies’, which on paper have all the capabilities they need, but in practice are ineffective. Co-operation at the EU level, especially in the industrial field, is needed to achieve economies of scale and to lead to a tangible improvement in European capabilities. To make a new transatlantic balance work, the US should:

1) Welcome European efforts and try to nudge them in the right direction.

Biden’s administration should welcome co-operative efforts that improve European capabilities. Member-states will be able to use the capabilities generated through EU defence initiatives not only in operations carried out within an EU framework but for all operations, including those under a NATO umbrella. The US should encourage the EU’s co-operation initiatives and try to steer them towards collaborative projects that lead to improved European capabilities in areas where NATO has identified shortfalls, and in areas where the EU can add most value, such as cyber-defence and military mobility. Washington should also push allies to ensure that any products of EU co-operation are aligned with NATO standards and fully interoperable with the alliance’s equipment.

2) Accept that more equal burden sharing implies more European independence.

The US should take the long view, accept that more equal burden sharing implies more European independence, and tolerate the growing pains that will accompany Europe’s ambitions. A more developed EU defence role will probably mean a degree of European divergence, especially on industrial matters, including fewer purchases of US arms. But this should be a price that is worth paying for Washington. A more self-reliant Europe would lighten the burden on the US and provide the basis for a renewed transatlantic security partnership.

Conclusion

Europeans should not be tempted to act as if Trump’s presidency never happened. It would be a mistake for them to relax and abandon their defence efforts now that Biden has won. Trumpism in some form is likely to endure, meaning that Europeans cannot be sure whether Biden’s successors will be committed to European security. Moreover, deep shifts are underway in US foreign policy which will mean that the US is likely to be less focused on Europe in the future. Even if another Democratic president were to follow Biden, foreign policy isolationism has become prevalent in significant parts of the American left. Europeans have to take on more responsibility for their own security, both for their own sake and to strengthen the relationship with the US. This will not be easy, especially in the context of the COVID-19 induced economic slump and the defence cuts that may follow. Nevertheless, Europeans have little choice but to try.

Instead of endlessly debating labels, Europeans should focus their efforts on how to improve their security and defence capabilities – and then actually use them if necessary. Europeans do not need to choose between pursuing their security through the EU on the one hand, or through NATO and the alliance with the US on the other, nor should they. Instead, they need to invest in their ability to act together to secure their neighbourhood, both within the EU and through other frameworks, in order to be able to act alone if the US will not. This need not undermine NATO or the EU’s relations with the US. Instead, a stronger and more confident Europe will be better able to look after its own security and place the transatlantic bond on a more solid footing.

2: Ben Barry and others, ‘Defending Europe: Scenario-based capability requirements for NATO’s European members’, IISS, May 10th 2019.

3: Nan Tian and others, ‘Trends in world military expenditure, 2019’, SIPRI, April 2020.

4: ‘The Secretary General’s annual report’, NATO, March 19th 2020.

5: ‘US warns against European joint military project’, Financial Times, May 14th 2019.

6: Aaron Mehta and Joe Gould, ‘Where President-elect Joe Biden stands on national security issues’, Defense News, November 8th 2020.

7: While negotiating the 2021-2027 EU budget, European leaders substantially cut funding for the European Peace Facility (from €10.5 billion to €5 billion), the European Defence Fund (from €13 billion to €7 billion) and military mobility (from €6.5 billion to €1.5 billion).

Sophia Besch, senior research fellow and Luigi Scazzieri, research fellow at the Centre for European Reform

December 2020

This policy brief was written thanks to generous support from the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. We are grateful to the former head of its UK and Ireland office, Felix Dane, for his support with the initial concept and design of the project. We are also grateful to the large number of officials, former officials and experts whose views, shared off the record in two workshops, helped to inform our analysis.

View press release

Download full publication

Comments

'1) Focus on improving Europe’s capacity to act rather than on abstract debates.' - Capacity to act against what/ whom?

'2) Ensure that EU initiatives deliver.' - Initiatives to deliver what?

and

'3) Focus on improving readiness and willingness to act.' - Readiness for what and willingness to act against whom?

One might argue that the answers to the above need to converge to a high degree in order to make a real impact.