EU-UK relations: Will 2026 be the year to reset the reset?

- The Labour government came into office in July 2024 promising to reset the UK’s relationship with the EU. The May 2025 EU-UK summit seemed to presage a new era in relations. But does the reset go far enough?

- The Labour government’s red lines (no return to the customs union; no return to the single market; no return to freedom of movement) limit what the reset can achieve. There has been progress on some of the UK’s initial objectives for the reset, but not all.

- The EU-UK summit in May 2025 produced a ‘Common Understanding’ listing 20 areas of co-operation, and many more subsidiary topics. Some topics – such as co-operation on international development assistance, or health security – that ought to be easy wins have turned out not to be. There have been some successes: the UK is rejoining the Erasmus+ programme for educational and training exchanges, at least for a year.

- In other areas, discussions are bogged down: the UK was slow even to agree to the principle of a ‘youth experience scheme’, to allow young Britons to live and work in EU countries and young EU citizens to live and work in the UK for a period. Both sides agree that UK integration into the European electricity market would be mutually beneficial. But the EU wants the UK to contribute to ‘cohesion policy’ (by providing funding to help poorer regions of the EU catch up economically with richer ones) as the price of partial integration into the single market, in this and other areas, and the UK is resisting.

- The Security and Defence Partnership (SDP) was supposed to clear the way for the UK to negotiate a separate agreement with the EU, giving UK firms the ability to play a major part in defence procurement projects under the EU’s Security Action for Europe (SAFE) programme. In a significant setback to the reset, however, negotiations broke down – largely because the EU demanded an up-front payment amounting to around 10 per cent of the UK’s annual defence budget. This outcome may benefit some individual EU-based defence firms, but it will weaken European defence as a whole. Some in the EU seem to be having second thoughts about excluding the UK from the programme.

- Overall, though there has been some progress in implementing what was agreed at the May summit, momentum has been lost. Both sides bear some responsibility. Both are transactional in their approach to the relationship, and miss the bigger picture. Both, in their different ways, have been scarred by the experience of Brexit, limiting their willingness to be more creative in strengthening their partnership.

- The review of the implementation of the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) must take place this year, and there should be another EU-UK summit. Five things are likely to influence the further development of the relationship in 2026:

- The behaviour of Donald Trump. His support for far-right parties in Europe and his threats to Greenland are making the case for Europe, including the UK, to become less dependent on the US for defence. It may even increase the pressure on the UK government to seek a wider rapprochement with the EU.

- The evolution of Russia’s assault on Ukraine. If Ukraine’s situation deteriorates further, European leaders will have to grapple with a possible need to deploy their own forces in or over Ukraine to support it. The EU and the UK will need to work together to tighten sanctions on Russia.

- The state of the EU and UK economies. None of the UK’s other trade deals can promote as much economic growth as closer integration with the EU’s internal market; but the UK is also one of the EU’s most important trading partners – the Union too would benefit from lower barriers, albeit less.

- UK domestic politics. Faced with the rise of Reform UK, the government can either double down on emphasising national sovereignty and refusing to restore some of the links broken by Brexit; or it can prioritise more integration with the EU as a way to generate growth. So far, there are signals pointing in both directions.

- The attitude towards the UK of the leaders of the EU and the member-states, including those like Germany that have good relations with London. If they can put the bad feelings and distrust of the Brexit negotiation period behind them, there will be more chance of progress in the areas identified at the EU-UK summit meeting in 2025. If they cannot, or if they give no clear instructions to their representatives in Brussels to change course, the relationship is likely to remain limited and sometimes tense. The UK’s problem is that member-states may not want to offer the UK a better deal if they think a Reform UK government will tear it up in a few years; but the economic effect of the absence of such a deal may make a Reform victory more likely.

- The world of 2026 is very different from the world of 2016, when the UK voted for Brexit. Neither the UK nor the EU seems to appreciate the scale of the changes. The UK-US special relationship has been severely damaged, and the rules-based international order has in many respects disintegrated. The EU and UK need a fundamental rethink of how they can enhance their security and prosperity by working together for European strategic autonomy.

The UK Labour Party’s manifesto, published in June 2024, promised to “reset the relationship” between the UK and the EU following Brexit and to “seek to deepen ties with our European friends, neighbours and allies”.1

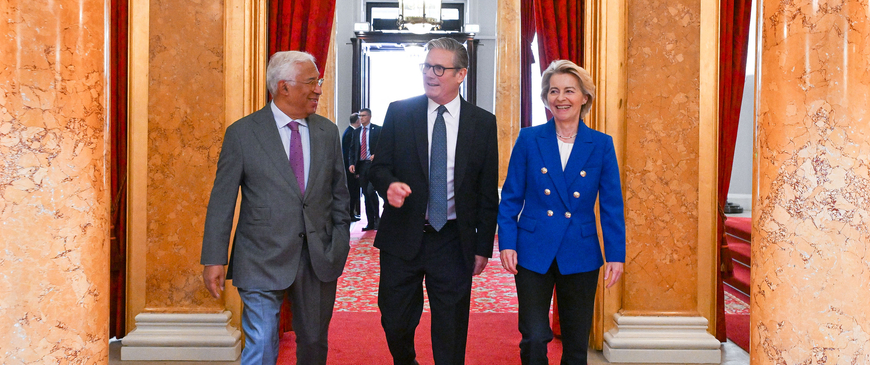

Since the Labour government came into office in July 2024, there have been new bilateral treaties with France and Germany; and at the EU-UK summit held in London in May 2025, the parties issued three documents on their future relationship:

- a joint statement setting out a new strategic partnership between them – largely a recitation of international issues on which the two sides already agree;

- a more operational ‘Common Understanding’, pointing to possible future co-operation in a wide range of areas;

- a Security and Defence Partnership (SDP), which, among other things, was designed to open the way to UK participation in EU defence industrial projects.2

The summit seemed to presage a new era in post-Brexit relations. The question is whether the reset and the EU’s response to it go far enough – bounded as they are by the Labour manifesto’s red lines of no return to the single market, the customs union or freedom of movement, and the EU’s mantra of ‘no cherry-picking’.

The external threats to the EU and the UK have grown since the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) came into force in 2021. Russia is not only continuing its war of aggression against Ukraine; it is also mounting increasingly violent hybrid attacks against other European countries. China is using its economic muscle in ways that threaten the viability of many parts of European industry, in the EU and the UK.3 And the US is becoming more protectionist, more erratic as an international actor, more hostile to mainstream European political parties and less willing to defend Europe. In his speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2026, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney described the global situation as “a rupture in the world order”.4

The next EU-UK summit meeting and the scheduled 2026 review of TCA implementation offer the chance – if both sides want it – to establish a much closer partnership, in the interest of enhancing their security and prosperity; but they could also decide that there are fewer political risks in staying within current boundaries, even if that leaves them collectively weaker.

This policy brief examines what the UK-EU reset has achieved so far; looks at the prospects for 2026 – ten years after the UK voted to leave the EU; and sets out what more the EU and the UK could do to respond to the common challenges they face.

What has the reset achieved so far?

The reset was always destined to make more progress in some areas than others. The Labour government’s red lines ruled out a transformation in the trade and economic relationship with the EU. Still, the 2024 manifesto promised to tear down “unnecessary barriers to trade”, and made four specific pledges:

- to “seek to negotiate a veterinary agreement to prevent unnecessary border checks and help tackle the cost of food”;

- to help UK artists, for whom mounting a European tour had become a nightmare of customs documents and work permits;

- to secure an agreement with the EU on mutual recognition of professional qualifications, to help open up markets for UK service exporters;

- to “seek an ambitious new UK-EU security pact”.

The Labour government’s red lines ruled out a transformation in the trade and economic relationship with the EU.

The last of these goals could be said to have been achieved, with agreement on the SDP at the EU-UK summit – although in some areas implementation is already running into trouble (see below). The others are at various stages of negotiation, or none at all.

The ‘veterinary agreement’– more accurately, a sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) agreement to make trade in food and agricultural products easier – required the EU to adopt a negotiating mandate, which it did in November 2025, enabling formal negotiations to start.

At the time of writing, musicians’ grievances about the barriers to touring in the EU have not been addressed. The Common Understanding recognised “the value of travel and cultural and artistic exchanges, including the activities of touring artists”, but the only commitment from the EU and UK was to “continue their efforts to support travel and cultural exchange”. The recently formed EU-UK umbrella group ‘Cultural Exchange Coalition’, which brings together more than 80 organisations representing artists, technical personnel and businesses involved in music, theatre and visual arts, says that post-Brexit arrangements are failing “audiences, artists and venues”, causing economic damage and weakening cultural connections between the EU and the UK.5

There has been no progress on mutual recognition of professional qualifications either, though the Common Understanding promises a dedicated EU-UK dialogue on some aspects of trade in services, which would cover this issue, among other things. Recognition of qualifications and “the regulatory environment for skills and professionals” were on the agenda for the meeting of the TCA’s Trade Specialised Committee on Services, Investment and Digital Trade in October 2025.6 But only one proposal, on mutual recognition of architects’ qualifications, seems to have reached the stage of discussion between the EU and the UK, and the “dedicated dialogue” has not yet begun.7

The May summit agreements added many more areas of potential co-operation to the original four in the Labour manifesto. Follow-up discussions have been divided among ten thematic ‘tables’. Some of these involve formal negotiations with a view to reaching legally binding agreements, and have already started work, such as those covering UK participation in the SAFE programme; youth mobility; and integration of the UK into the EU electricity market. Others are at a very early stage. In every case where the UK would like integration into or closer association with the EU’s internal market, there is a wide gap between what the EU wants the UK to pay in return for improved trading conditions, and what the UK regards as a reasonable contribution to EU administration costs.

There have been some concrete achievements since the May summit, and 2025 ended on a high note, with the announcement that the two sides had agreed that the UK would rejoin the Erasmus+ programme for educational and training exchanges from 2027, and that negotiations on UK participation in the EU’s internal electricity market would start shortly. Details of progress in implementing each point in the Common Understanding and the SDP are set out in the annex to this policy brief.

Overall, however, there has been a sense on both sides of lost momentum since May. Then, European Council President António Costa spoke of “a new chapter in the relationship between the UK and the EU – the start of a renewed and strengthened strategic partnership”.8 European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen described the EU and UK as “historical and natural partners standing side by side on the global stage, facing the same challenges, pursuing the same objectives, like-minded, sharing the same values”.9

Labour has been disappointingly willing to tolerate the continuing economic damage caused by being outside the EU.

Some of the reduced impetus was down to the British government’s continued reluctance for much of 2025 to confront eurosceptics in the media and the political opposition – even though the Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that Brexit will make the UK’s GDP 4 per cent smaller in the long term, and a recent study by the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) put the figure even higher – showing that Brexit had already reduced GDP by 6-8 per cent.10 For a government that came into office with “kickstart economic growth” as the first priority in its manifesto, Labour in 2025 was disappointingly willing to tolerate the continuing economic damage caused by being outside the EU, in the (vain) hope of avoiding accusations of betraying Brexit.

It was noticeable that at the post-summit press conference, Costa and von der Leyen stressed the benefits to both sides of increased co-operation, while Starmer focused exclusively on what the UK would get from what he described as a “new partnership between an independent Britain and our allies in Europe”, and stressed that the government would stick to the manifesto’s red lines.11 When Thomas-Symonds spoke about the UK’s future relationship with the EU in August 2025, he continued to insist that “without rejoining the single market, or the customs union, and without reopening freedom of movement, we can still build a valuable relationship with the EU that genuinely benefits Britain”.12 In reality, it will be a relationship that brings modest benefits, and is less valuable than it could be if the government were willing to be bolder.

But the EU also needs to take a share of the blame for failing to respond to the needs of the moment. The SDP states, correctly, that the UK and the EU share a responsibility for the security of Europe, and that “the UK is an essential partner for the EU in the area of peace, security and defence”. But in conversations with EU officials, there is still a hint that the UK should be made to pay a price for Brexit, or held up as an example of the negative consequences of voting to leave the Union. Member-states, and especially their permanent representations in Brussels, which sit on the EU working party for relations with the UK, are also inclined to insist that the UK should not be allowed to cherry-pick and participate in some parts of the internal market but not others – even as the EU debates partial integration of Ukraine and other candidate countries into the single market. The more favourable treatment the EU has sometimes given countries like Canada and South Korea is suggestive of a desire to keep punishing the UK for the 2016 referendum.

The handling of negotiations over SAFE epitomises the EU’s willingness to put narrow national or sectoral interests ahead of the common good. UK participation in SAFE would have allowed UK firms to play a major role in projects to improve Europe’s defence capabilities. Thereby it would have increased Europe’s strategic autonomy, at a time when the possibility of defending Europe without US help seems an increasingly realistic scenario. While some EU manufacturers, particularly in France, may profit from the UK’s exclusion, European defence and security overall is likely to suffer.

There are hints of regret from the EU at the exclusion of the UK from at least the first phase of SAFE. Some officials admit privately that the initial demand that the UK pay €6.5 billion up front, though based on a calculation of how much the UK might benefit from participation in the programme, was not scrutinised closely enough because the negotiations were so hurried. If it had been, someone might have realised that the figure amounted to almost 10 per cent of the UK’s defence budget. Starmer has indicated that he might be interested in trying to negotiate UK participation in a second phase of SAFE, though there is no funding for that in the current EU budget. Some member-states, including Germany and Italy, would support the UK, though France remains firmly opposed.13

The EU accuses the UK of being transactional in its approach to the relationship, when London tries (for example) to ensure that rejoining Erasmus+ will not force it to bear the costs of large numbers of EU citizens paying domestic rather than overseas student fees, while smaller numbers of UK citizens go in the other direction. But the EU’s approach to UK involvement in EU programmes is just as transactional.

Prospects for 2026

The new year has begun with a bang. Trump attacked Venezuela and seized President Nicolás Maduro and his wife. He renewed US threats to annex Greenland and then announced that he would impose tariffs on EU countries and the UK as long as they continued to support for Denmark’s sovereignty in Greenland, before reversing course on the basis of a vague agreement with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte. On these issues, the UK position has been close to the European centre of gravity – trying to show support for international law and (in the case of Greenland) for Denmark, a European ally, without provoking Trump’s wrath. The UK approach has only been partially successful: after Starmer supported the Danish position on Greenland, Trump threatened the UK with tariffs and attacked the treaty the UK had negotiated with Mauritius over the status of the US military base on Diego Garcia (which the US had previously approved), describing it as “an act of great stupidity”.

The transition away from the US will be even harder for the UK than EU member-states.

Trump’s behaviour is likely to be one of the forces shaping the EU-UK relationship in 2026. The vision of “Promoting European greatness” set out in the US National Security Strategy (NSS) published in November 2025 undermines decades of transatlantic solidarity and promises US support for “patriotic European parties” at the expense of mainstream democratic movements in Europe. If the administration takes the NSS as a blueprint for action, governments in France, Germany and the UK (at least) can expect to find the US government working for the victory of populist right-wing parties in future elections.14 The UK seems to be in Washington’s sights because of the number of immigrants and descendants of immigrants in its society, and the “elite-driven, anti-democratic restrictions on core liberties in… the Anglosphere” – in other words, efforts to regulate the behaviour of US-based internet platforms and social media like Elon Musk’s ‘X’, and to prevent hate-speech.

The Trump administration’s actions, particularly its threats to seize Greenland by force – even if cancelled at present – are likely to keep making the case for Europe, including the UK, to reduce its defence dependency on the US. The US National Defense Strategy (NDS) is likely to increase the momentum towards European defence autonomy: it states that “Europe taking primary responsibility for its own conventional defense is the answer to the security threats it faces”, and makes clear that the US will provide less support for Europe in future.15

As Friedrich Merz – previously a staunch Atlanticist – said on the night of his victory in the Bundestag elections in February 2025, “My absolute priority will be to strengthen Europe as quickly as possible so that, step by step, we can really achieve independence from the USA”.16 Psychologically, the transition away from the US will be even harder for the UK than EU member-states, after almost seven decades of reliance on the ‘special relationship’ with Washington. The EU and individual member-states would benefit from encouraging the UK to help Merz achieve his objective, rather than trying to extract a price for closer co-operation.

A second influence on the development of relations will be the evolution of Russia’s assault on Ukraine. The UK, like the European Commission and most member-states, has been a strong supporter of Ukraine. The UK and France have led the ‘coalition of the willing’, working to put together security guarantees and a ‘reassurance force’ to deploy in Ukraine in the event of a ceasefire.

The US NSS implicitly rejects European efforts to support Ukraine’s efforts to defend itself, however, stating “The Trump Administration finds itself at odds with European officials who hold unrealistic expectations for the war perched in unstable minority governments, many of which trample on basic principles of democracy to suppress opposition. A large European majority wants peace, yet that desire is not translated into policy, in large measure because of those governments’ subversion of democratic processes.” In US-Ukrainian negotiations in Paris on January 6th-7th 2026, the US still appeared to be pressing Ukraine to concede territory that Russia has been unable to occupy in almost four years of fighting – contrary to the advice of European leaders.

European leaders cannot afford to stand aside as Trump tries to force Ukraine into capitulation.

If Ukraine’s military and social situation deteriorates further, European leaders, including Starmer, will have to grapple with a possible need to deploy forces, or at least put aircraft in Ukrainian airspace, to reinforce Ukraine’s own efforts. To increase the economic pressure on Russia, the EU will also need the UK to join in sanctions on providing maritime services for ships carrying Russian oil and gas, given London’s central role in areas such as insurance and shipbroking. European leaders cannot afford to stand aside as Trump tries to force Ukraine into a capitulation that would increase the Russian threat to the rest of Europe – a threat downplayed in the NDS, which describes Russia as “a persistent but manageable threat to NATO’s eastern members”.

A third factor will be the state of the economy, especially in the UK but also in the EU. One of the reasons the UK government gives for sticking to its red lines is that rejoining the customs union or the single market would mean giving up the advantages it has gained from being able to sign free trade agreements independently. The reality, however, is that deals signed since Brexit with Australia, New Zealand, India and others will increase GDP by about 0.2 per cent, according to the government’s own figures. That is not much compensation for the loss of 4-8 per cent of GDP as a result of leaving the EU single market and customs union.17 Even a full free trade agreement with the US – if such a thing were on offer from the Trump administration, rather than a partial deal that increases tariffs on UK goods and is subject to unpredictable changes whenever Trump feels like it – would only increase GDP by a further 0.15 per cent.

The EU remains by far the UK’s biggest trading partner, and its share in imports and exports is only slightly smaller than before Brexit. In 2024, UK exports of goods and services to EU member-states made up 41 per cent of total exports, compared with 42 per cent in 2019. For imports, the figures were 50 per cent in 2024, compared with 51.4 per cent in 2019. The UK’s next most important partners in 2024 were the US (22.5 per cent of exports, 13.2 per cent of imports) and China (3.6 per cent of exports, 7.7 per cent of imports).18 But the UK is also a significant partner for the EU – the third largest in goods, behind the US and China, and the second largest in services, behind the US. The EU as well as the UK would benefit from greater integration and the removal of as many as possible of the barriers to trade in goods and services created by Brexit. In that respect, the TCA regime was a better deal for exporters of goods (especially larger firms, for whom the cost of extra bureaucracy is more manageable) than for exporters of services.

A fourth factor will be UK domestic politics. On May 7th there will be elections to the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Senedd and a number of English local authorities. Opinion polls suggest that Nigel Farage’s anti-EU Reform UK party will do well, and that Labour will do very badly.

This will create conflicting pressures on the government. Reform’s success could lead to the government doubling down on an approach to the EU which emphasises UK sovereignty and a refusal to integrate more closely with the single market, in an effort to persuade former Labour-voting Reform supporters to return to Labour; or it could lead the government to prioritise more integration as the way to ensure economic growth, ignoring criticism from the Conservatives and Reform UK, in the hope that growth will have more resonance than Brexit purity with voters in general, and will prevent Labour losing votes to more explicitly pro-EU parties including the Liberal Democrats, the Greens and nationalist parties in Scotland and Wales.

In his January 4th 2026 BBC interview with Laura Kuenssberg, Starmer hinted that he might take the latter approach, telling her “if it’s in our national interest… to have even closer alignment with the single market then we should consider that”, but stressing that he would rule out a customs union with the EU (since that would involve giving up the other trade agreements the UK has reached with non-EU countries) and any return to the free movement of labour. The government is reportedly planning to introduce a bill allowing for dynamic alignment with EU rules relevant to areas where it is negotiating for greater integration into the EU market, including food standards and emissions trading.19

One of the considerations for Starmer will be how to position himself on the EU in the event of a challenge to his leadership of the Labour Party, if the May 2026 elections go as badly as predicted. Among his potential rivals for leadership of the Labour Party, health secretary Wes Streeting has hinted that the UK should have a customs union with the EU, while the mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, has said that he hopes the UK will rejoin the EU in his lifetime.

Domestic UK politics as well as the global situation will also affect the final factor in the evolution of relations in 2026 – the EU’s attitude. Berlin may have a special role to play in encouraging both the UK and the EU to cross their red lines and seek a more far-reaching rapprochement: the UK-Germany Kensington Treaty states that a positive development of the EU-UK relationship is in their shared interests; and Merz’s remarks on strengthening Europe in order to achieve independence from the US could be read as including non-EU European countries like the UK. Other EU member-states with particularly close relations with the UK, such as the Nordic and Baltic countries, might also be in favour of putting the toxic experience of Brexit behind them. Then they could face threats from Russia and elsewhere as part of a wider European coalition (and perhaps an even larger grouping, including Canada and other democratic partners).

Berlin may have a special role to play in encouraging more far-reaching EU-UK rapprochement.

The conundrum for the EU is that while a recent opinion poll put UK voters’ support for rejoining the EU at 58 per cent, it also showed that if an election were held now, Reform UK would probably be the largest party in the Commons.20 Member-states may feel that this shows that the UK itself has not put Brexit behind it. In that case, it would be tempting to leave officials in Brussels to continue on their current course, turning every proposal for an improvement in relations into a fight, even when there are benefits to both sides from progress, thereby limiting the potential gains for both sides and ensuring that the EU-UK relationship remains tense and sub-optimal.

Member-states may also be reluctant to offer the UK a better deal, let alone start thinking about conditions for the UK to rejoin the EU, if there is a serious prospect of a future Reform UK government putting everything into reverse a few years later. There are already reports that the EU is demanding a ‘Farage clause’ in the negotiations for an SPS agreement, obliging a future UK government to pay compensation to the EU if the UK withdrew from the agreement.21 The UK government may end up in Catch-22: it needs a better trade relationship with the EU to drive growth and reduce Reform UK’s chances of leading the next government, but the EU will only give it a significantly better deal once it is sure that Reform UK will not gain power.

There are two timetables for the EU and UK to keep in mind in 2026. First, the two sides agreed at their May 2025 summit to hold such meetings annually – and though no exact date has been agreed yet for the next summit, the expectation is that it will be held in May, after the UK local elections. Second, the TCA obliges the EU and UK to conduct a joint review of the implementation of the agreement itself, any supplementary agreements “and any matters related thereto” five years after its entry into force – in other words, starting around May 1st 2026.

Both the timing and content of the next summit are up to the EU and UK to decide, but such meetings always create pressure for ‘deliverables’ – something for leaders to point to show that the meeting was a success, and they did not meet just for the sake of it. So far, the message from both sides seems to be that by the time of the next summit they want to be able to show concrete progress – though probably not final agreement – on some of the key dossiers identified in the Common Understanding and the SDP. That is a reasonable minimum aim, but not a dramatic advance. As the analysis in the annex shows, the two documents between them lay out a very broad agenda, but in many areas not a very deep one; there is room to take implementation much further.

The timing of the TCA review is fixed, but its content is also up to the parties to decide. In evidence to the House of Lords European Affairs Committee after the EU-UK summit, Thomas-Symonds suggested that the review had been overtaken by the summit decisions, since some of these (for example, the UK rejoining the single market for electricity) would involve amendments to the TCA. But the review will still have to take place; the question is how substantive the two sides want it to be. It could be a cursory examination of implementation problems, or they could supplement the TCA with agreements on new areas of co-operation.22

For most of the period since it entered into force, the EU’s position has been that the 2026 review should be a technical process, looking at issues that have arisen with implementation, not a major review of the substance of the TCA. Maroš Šefčovič, the commissioner responsible for negotiations with the UK, warned in 2023 that the TCA review clause did not “constitute a commitment to reopen the TCA or to renegotiate the supplementary agreements”.23 Others, particularly on the pro-EU side in the UK, had greater ambitions. Starmer himself, while still leader of the opposition, said that he wanted to use the review to try to get “a much better deal”.24 The May 2025 summit showed the Commission conceding that the review should be at least slightly more ambitious. The Common Understanding has launched negotiations on issues such as UK integration into the EU electricity market that will require amendments to the TCA. The SDP covers ground that the Johnson government refused to discuss with the EU, and some of the elements in it could also end up as amendments to the TCA.

In the end, however, if the UK sticks to its red lines and the EU views every change to the TCA as an item that the UK must pay for, the best the review can achieve is incremental progress. Is that enough, given the pressures on both the EU and the UK? As US tariffs and Chinese overcapacity squeeze the EU and the UK alike, Europeans in general could benefit from reducing barriers to trade in goods and services throughout Europe, not just inside the EU. Agreements on SPS and electricity trading will improve things slightly, but they will not be game-changing.

In the security sphere also, Russia continues to arm itself, beyond even what it needs for its war in Ukraine, and the US has proclaimed its reduced interest in defending Europe. If the UK and EU both camp on their positions in relation to SAFE, both will be the losers in terms of their own security, at a time when they most need to work together.

Conclusion

The world in 2026 is very different from that in 2016, when the UK voted to leave the EU, or even that in 2021, when the EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) entered into force. Progress in the EU-UK relationship since the May 2025 summit does not adequately reflect the scale of the changes. Though the relationship is closer than it was, advances have been gradual. Both sides (but especially the EU) often act as though every move towards closer partnership is zero-sum.

The next stage of the EU-UK reset cannot be a minor upgrade to individual elements of the relationship.

Neither side seems to have grasped the threats to them from this new world. The UK is clinging on to a special relationship with the US that has been gravely, perhaps irreparably, damaged, while Labour’s red lines on the single market, customs union and freedom of movement limit potential rapprochement with the EU and the consequent economic benefits. In the EU, there still seems to be a lingering desire to punish the UK for Brexit, and to extract a price for every step towards greater integration, even when both sides will benefit from it. But the rules-based international order on which both have relied for their security and prosperity – which has often looked threadbare in the past – has more or less disintegrated under attacks from Moscow and Washington.

Europe as a whole needs to work together more closely if it does not want to be reduced to a group of vassals of one or another great power. European strategic autonomy – long viewed in London as a French fantasy – has become a necessity. The wider the gap between US and European values and interests becomes, the harder it will be for the UK to stand aloof from the rest of Europe without damaging its own interests. For Europe too, there is more to be gained from a closer partnership with the UK than from keeping it at arm’s length. The next stage of the EU-UK reset cannot be a minor upgrade to individual elements of the relationship. It should instead be the moment for a fundamental rethink of how both sides can enhance their security and prosperity and Europe’s ability to stand up for its interests. This is the year to reset the reset.

2: ‘UK/EU Summit - Key documentation’, gov.uk website, May 19th 2025.

3: See for example Sander Tordoir, Nils Redeker and Lucas Guttenberg, ‘How buy-European rules can help save Europe’s car industry’, CER policy brief, October 23rd 2025.

4: ‘Davos 2026: Special address by Mark Carney, Prime Minister of Canada’, World Economic Forum, January 20th 2026.

5: ‘Our mission’, Cultural Exchange Coalition website.

6: ‘The fifth trade specialised committee on services, investment and digital trade under the UK–EU Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA), Thursday 23rd October 2025 – agenda’, European Commission, October 16th 2025.

7: ‘Trade and Co-operation Agreement implementation report, 2023-2024’, gov.uk website, September 2nd 2025.

8: ‘Remarks by President António Costa at the joint press conference following the EU-UK summit in London’, European Council/Council of the European Union, May 19th 2025.

9: ‘Statement by President von der Leyen at the joint press conference with President Costa and UK Prime Minister Starmer following the EU-UK Summit’, European Commission, May 19th 2025.

10: Nicholas Bloom and others, ‘The economic impact of Brexit’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, November 2025.

11: ‘PM’s remarks at press conference with EU leaders : 19 May 2025’, gov.uk website, May 19th 2025.

12: ‘Speech on the UK’s future relationship with the European Union: Minister for the Constitution and European Union Relations Nick Thomas-Symonds delivers a speech on the UK’s relationship with the EU, hosted by The Spectator’, gov.uk website, August 27th 2025.

13: Sam Fleming and others, ‘UK and EU to renew talks on defence fund access’, Financial Times, January 23rd 2025 and George Parker, Leila Abboud, Peter Foster and Sam Fleming, 'UK to reconsider joining EU defence fund', Financial Times, February 1st 2025.

14: ‘National Security Strategy of the United States’, whitehouse.gov website, November 2025.

15: ‘2026 NDS: National Defense Strategy’, US Department of War, January 23rd 2026.

16: Tim Ross and Nette Nöstlinger, ‘Germany’s Merz vows ‘independence’ from Trump’s America, warning NATO may soon be dead’, Politico, February 23rd 2025.

17: Cited in John Springford, ‘The economic impact of Brexit, nine years on: Was the consensus right?’, The Constitution Society, June 23rd 2025.

18: ‘Trade and investment core statistics book’, gov.uk website, updated December 19th 2025.

19: Dan Bloom and Sophie Inge, ‘UK readies bill to move closer to EU’, Politico, January 6th 2026.

20: ‘The Mirror end of year poll’, Deltapoll, January 5th 2026.

21: Peter Foster, George Parker, Anna Gross and Andy Bounds, ‘EU demands ‘Farage clause’ as part of Brexit reset talks with Britain’, Financial Times, January 11th 2026.

22: Joël Reland and Jannike Wachowiak, ‘Reviewing the Trade and Co-operation Agreement: Potential paths’, UK in a Changing Europe, September 19th 2023.

23: Andy Bounds and Peter Foster, ‘Barriers to post-Brexit trade likely to ‘deepen’ further, warns EU’, Financial Times, June 12th 2023.

24: George Parker, ‘Keir Starmer pledges to seek major rewrite of Brexit deal’, Financial Times, September 17th 2023.

Read the annex: The state of play on implementation of the EU-UK Common Understanding and the EU-UK Security and Defence Partnership here.

Ian Bond is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform.

February 2026

View press release

Download full publication

This policy brief is the last of a three-paper CER/KAS project, ‘Navigating stormy waters: UK-EU co-operation in a shifting global landscape.’ The first policy brief was ‘Will EU enlargement create new models for the EU-UK relationship?’ by Luigi Scazzieri. The second was ‘China and Europe: Can the EU and the UK find a shared strategy?’ by Ian Bond.