China and Russia: Are there limits to 'no limits' friendship?

China has mostly offered Russia rhetorical support in its war against Ukraine. Beijing seems uncomfortable with Putin’s nuclear sabre-rattling. But China is unlikely to allow Russia to be decisively defeated.

When Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin met in Beijing in February 2022, they declared in a joint statement that “friendship between the two states has no limits, there are no ‘forbidden’ areas of co-operation”. Since then, Putin has tested this claim by launching a war of aggression against Ukraine – a country with which China previously had friendly relations. While China has been helpful to Russia in some areas, it has generally tried to appear neutral. It is in the West’s interest to keep China on the sidelines of Putin’s war; if it could be persuaded to exert some pressure on Russia to stop fighting, that would be a bonus.

It is in the West’s interest to keep China on the sidelines of Putin’s war.

With these aims in mind, there are five aspects of the China-Russia relationship for Western leaders to bear in mind as they calibrate their approach to Beijing:

the personal (between Xi and Putin);

the diplomatic (for instance, China’s co-operation with Russia at the UN);

the narrative (what Chinese media and commentators are saying about the war);

the economic (China’s trade with Russia and with the West);

the geostrategic (the impact of the war, and its outcome, on China’s interests and its ambitions to become the world’s pre-eminent power).

The personal

In two highly personalised systems, the relationship between Xi and Putin is bound to have a big impact on relations between their states. In 2013, Xi’s first foreign trip as president was to Moscow, where he told Putin “You and I are good friends”. Since then, the two men have stayed in frequent contact – probably no foreign leader has met or spoken to Putin as often as Xi in the last decade.

Xi’s regular personal engagement was important to Putin in 2014 and 2015, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and intervention in Ukraine’s Donbas region, when many contacts with the West were severed. Putin reciprocated in February 2022 when he was one of the few world leaders to attend the opening of the Beijing Winter Olympics – Western leaders having boycotted the games because of human rights violations in China’s Xinjiang province.

It remains unclear how much information about his planned attack on Ukraine, if any, Putin shared with Xi on that occasion. According to The New York Times, citing a Western intelligence report, Chinese officials asked the Russians not to launch their invasion during the Olympics. But the Chinese have subsequently suggested that they did not know what Putin was about to do. In any event, the war seems to have caused some cooling in relations. When Putin and Xi met in the margins of the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation summit in Samarkand in September 2022, Xi continued to refer to Putin in Samarkand as “my old friend”. But Putin’s televised remarks suggested that he and Xi did not see eye-to-eye on Ukraine: he talked of “the balanced position of our Chinese friends when it comes to the Ukraine crisis” and commented: “We understand your questions and your concern about this”.

The diplomatic

In international organisations, China has echoed some of Russia’s arguments for going to war, but has generally tried to avoid taking a firm position. In explaining China’s decision to abstain in a February 25th vote on a UN Security Council resolution condemning the invasion, the Chinese ambassador said that against the background of five rounds of NATO expansion, Russia’s legitimate security aspirations should receive attention and be addressed properly; he called for civilian casualties to be avoided; and he urged an immediate return to diplomatic negotiations. China (like India) has abstained in subsequent votes on the war in the Security Council and the General Assembly.

Since March, Chinese diplomacy has been guided by ‘four musts’, laid down by Xi:

The sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries must be respected.

The purposes and principles of the UN Charter must be fully observed.

The legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously.

All efforts that are conducive to the peaceful settlement of the crisis must be supported.

In practice China has focused more on highlighting Russia’s security concerns than protecting Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. There have been few direct contacts between Chinese and Ukrainian officials since the war began. At the UN Human Rights Council in March, China abstained in a vote to establish an international commission of inquiry to investigate Russian human rights abuses in Ukraine. In May it voted against a further resolution directing the commission to investigate possible Russian war crimes in areas recently liberated by Ukraine. While supporting peace efforts in general, China has not sought a mediating role for itself. The closest Xi has come to support for Ukraine was agreeing to the G20 Bali leaders’ declaration. This noted that there were different assessments of the situation and that the leaders had reiterated their national positions in their discussion of Ukraine; but it also quoted the UN General Assembly resolution of March 2nd, in which 141 countries “deplore[d] in the strongest terms the aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine”.

One possible red line for China is the use of nuclear weapons in the conflict. China has always insisted that it would only use its nuclear weapons to retaliate against a nuclear attack. By contrast, Russia’s 2020 nuclear deterrence policy allows for a nuclear response to a conventional attack “when the very existence of the state is under threat”. China seems uncomfortable with repeated hints from the Russian leadership that the use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine is not impossible: during German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s November visit to China, Xi told Scholz that the international community should oppose the threat or use of nuclear weapons and “prevent a nuclear crisis in Eurasia”. It is unclear, however, whether China would come off the diplomatic fence in the UN even if Russia used nuclear weapons in Ukraine.

The narrative

If China’s stance at the UN has been relatively neutral, its public narratives have regularly amplified Russian talking points. From the early stages of the war, Chinese media adopted the Russian position that the US and NATO were to blame. Beijing shares Russia’s negative view of NATO – particularly since the US persuaded European states that the alliance should pay more attention to the challenge from China. Analysis from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in May showed that over a nine-day period in March, 14 per cent of tweets from Chinese diplomats and overseas missions that touched on Ukraine attacked or blamed the West for the conflict; a further 17 per cent spread Russian disinformation about alleged US biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine. Research published by the European External Action Service’s East Stratcom Task Force (a unit which seeks to identify and counter disinformation) showed references to alleged Nazism in Ukraine surged in Chinese social media (including that aimed at overseas Chinese audiences) in response to Putin’s claim that one of his aims was to ‘denazify’ the country. But Beijing has not endorsed Putin’s illegal annexation of Ukrainian territory, presumably because of its own pre-occupation with territorial integrity.

The economic

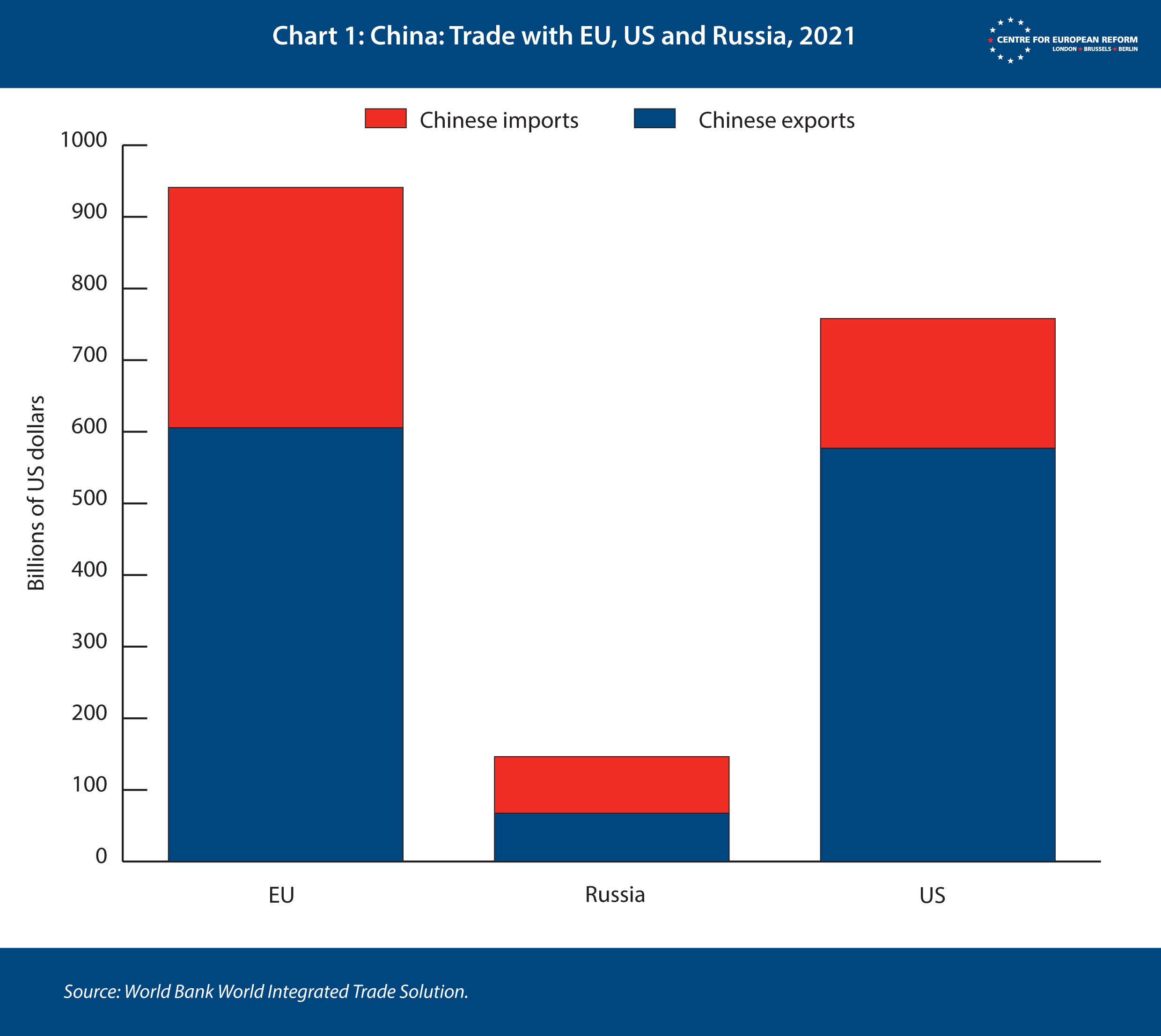

While China is the main trading partner of Russia (as it is of Ukraine), its combined trade with the EU and US in 2021 was almost 12 times its trade with Russia (see Chart 1). This may explain why, despite its pro-Kremlin and anti-NATO propaganda, Beijing does not seem to have supplied Russia with military equipment or sensitive items. US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan told the media in March: “We are communicating directly, privately to Beijing, that there will absolutely be consequences for large-scale sanctions evasion efforts” – consequences which China presumably wishes to avoid.

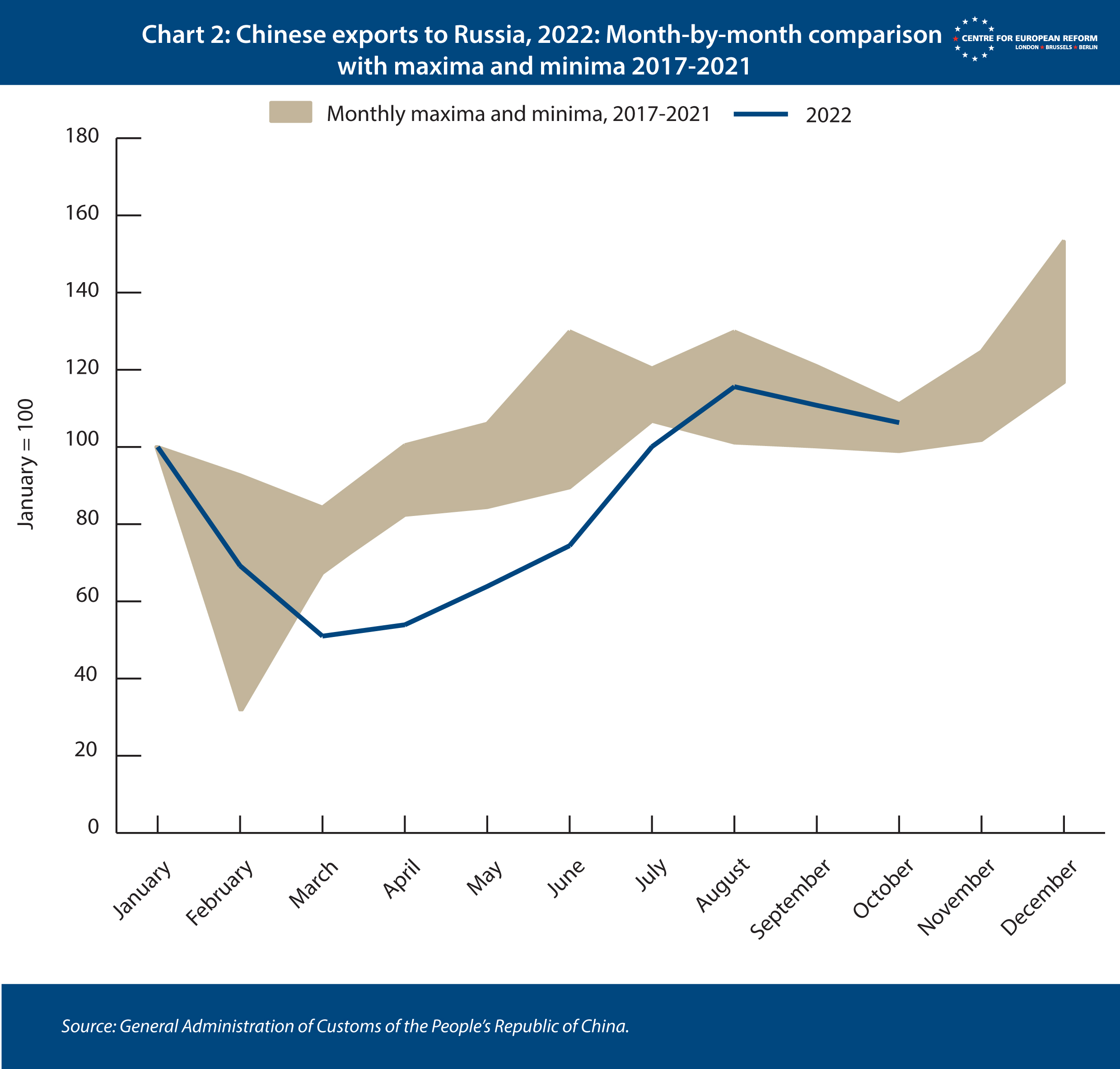

Chinese exports to Russia have fallen in the first quarter of each of the last six years, but fell significantly further and took longer to recover after the war began (see Chart 2) – perhaps as a result of US pressure, or the fear of it. The Russian trade representative in China explained in September that Chinese banks were often extremely cautious about dealing with Russian clients. But as time went on, previous growth in Chinese exports resumed. Overall, Chinese exports to Russia rose by almost 19 per cent year-on-year in the first ten months of 2022. According to Chinese customs data, exports of machinery and electrical goods (including computers and telephones), which fell year-on-year in each month from March to June, were up by more than 40 per cent year-on-year in August, September and October. One notable feature of their trade is the decreased use of the dollar and increased use of the Chinese yuan for payments, insulating the trading partners from US sanctions. In August, the Moscow Exchange reported that yuan-rouble trading turnover was 61 times higher than in December 2021, and predicted that yuan-rouble trading would exceed dollar-rouble trading in 2023. Meanwhile, seven of Russia’s largest firms have reportedly issued bonds worth 42 billion yuan (€5.7 billion) this year.

Meanwhile, China’s imports from Russia rose by 48 per cent year-on-year in the first ten months of 2022. Increased Chinese purchases of Russian oil and gas account for most of the change: according to the oil and gas industry news site Rigzone, around 20 per cent of China’s oil imports in the period from June to August 2022 were from Russia, compared with 16 per cent in 2021. China’s approach is pragmatic: according to Bloomberg, Urals crude from Russia was trading at a discount of more than $30 per barrel in November, having lost its European market. China (like India, which has also increased its imports of Russian oil) is happy to be the beneficiary; Russia gets some revenue, albeit at less than the full market price; while Europeans, forced to buy oil at higher prices from elsewhere, pay the biggest economic penalty.

Russia has also supplied China with more gas than in previous years. This results from increased Russian production filling the ‘Power of Siberia’ pipeline (due to reach full capacity in 2025), rather than diversion of gas that would otherwise have gone to Europe. Though Russia, China and Mongolia have discussed a ‘Power of Siberia 2’ pipeline, which would connect to gas fields in Western Siberia that currently supply Europe, construction has not yet begun, and it will be some years before any gas flows along that route. China can afford to wait for the new pipeline until Russia is willing to offer the gas from it at a low price.

The geostrategic

The geostrategic impact of the conflict on China’s interests is complicated. When Putin launched his invasion, four months after the ignominious retreat of the US and its allies from Afghanistan, the Chinese leaders probably expected that Russia would achieve a quick victory that would further undermine Western pretensions to global leadership. China would then be in a stronger position to reshape the global order for its own benefit. Instead, however, the West has maintained a united front and has helped Ukraine to hold the Russians at bay and in some areas even to push them back.

China might welcome a prolonged and inclusive conflict in Europe.

In one way, China might now welcome a prolonged and inconclusive conflict in Europe. The effort to keep Ukraine supplied and to reinforce the US presence in Europe to reassure NATO allies might complicate US plans to focus more of its military effort on the Indo-Pacific region. Even with a defence budget of over $850 billion for 2023, the US may struggle to ensure Ukraine’s military success and simultaneously counterbalance China’s growing military presence in presence in Asia and the Pacific and above all around Taiwan.

At the same time, it is not in China’s geostrategic interest to help the West weaken Russia – a like-minded country and a strategic partner. As a matter of principle, China opposes sanctions imposed without UN Security Council endorsement. Even in the unlikely event that Beijing thought of joining Western sanctions, it would hardly contribute to undermining Russia’s economy unless there was some benefit to China. But as the influential Chinese scholar Yan Xuetong wrote in May: “condemning Russia publicly and siding with those enforcing sanctions against it would only open the door for the United States to impose secondary sanctions on China itself”.

Moreover, were there to be a real threat to Russia’s internal stability, China would probably do what it could to shore up Putin’s regime. As the Chinese academic Xu Wenhong wrote in September: “Friendly relations have helped both sides to better safeguard their interests without having to bother much about a threat to their national security from each other”. A Russia in chaos or (still worse from China’s perspective) one in which Putin was replaced by a more pro-Western figure – however unlikely either scenario might seem – would force China once again to guard its long border with Russia.

Conclusion

Some EU politicians think that with enough encouragement China might put pressure on Russia to negotiate an end to the war. French President Emmanuel Macron seems to be among them: after meeting Xi in the margins of the G20 summit in Bali on November 15th-16th, he announced that he would visit China early in 2023, and that he was “convinced that China can play a more important mediation role”.

Other European officials and many US politicians and commentators are more pessimistic: they think that China and Russia are working together against the West, and that the only way to prevent China helping Russia’s military effort in Ukraine is to threaten it with sanctions. As Fred Kempe, President and CEO of the Atlantic Council think-tank in Washington put it: “Russia and China are throwing in their lot with each other in an unprecedented manner in each other’s regions and around the world”.

The evidence suggests that there is little likelihood that China would want to act as a mediator, as Macron hopes, even if the parties to the conflict wanted it to. The relationship between Beijing and Moscow may be more complex than Kempe suggests – China may not like everything that Russia is doing – but at least Moscow is not actively working against Beijing, and shares much of its world view. The best that the West can hope to achieve is to keep China more or less neutral, deter it from actively undermining Western sanctions (particularly those preventing technology transfer to Russia) and perhaps get it to rein in some of its disinformation activities. If European leaders want to play ‘good cop’ to the Americans’ ‘bad cop’, stressing the benefits to China of working together to end the war rather than threatening it with punishment for supporting Russia, so be it. But they should be realistic: China will pursue its own interests in its relations with Russia, and they are not the same as the West’s.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform.

This insight was written with support from Aspen Institute Italia, and reflects inter alia issues raised in an Aspen Institute Italia/Centre for European Reform conference, ‘EU-US: What to make of Russia and the competition with China’, held on July 12th 2022.

Add new comment