Is development aid a victim of the EU budget deal?

The COVID-19 pandemic has hindered the Commission’s plans to reform its development policy. But though the EU will provide less external assistance than planned, its administration can be improved.

The financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on member-states severely affected the Commission’s ambitious proposals to increase the EU’s external action budget. But the proposed reform of EU aid is not only about the numbers. If the EU is to be a more efficient and coherent international actor, it needs to improve the management of its external expenditure. This insight looks at what the reform of the EU’s development policy means for its global ambitions, and how to make the most of it. The COVID-19 pandemic has hindered the Commission’s plans to reform its development policy. But though the EU will provide less external assistance than planned, its administration can be improved.

If the EU is to be a more efficient and coherent international actor, it needs to improve the management of its external expenditure.

The financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on member-states severely affected the Commission’s ambitious proposals to increase the EU’s external action budget. But the proposed reform of EU aid is not only about the numbers. If the EU is to be a more efficient and coherent international actor, it needs to improve the management of its external expenditure. This insight looks at what the reform of the EU’s development policy means for its global ambitions, and how to make the most of it.

As the coronavirus pandemic spread across the world, the EU soon realised that unless it offered prompt support to poorer countries beyond Europe, the economic, security and humanitarian price of the crisis would be much higher for the Union. Since April 2020, the European Commission has managed to raise almost €36 billion from the EU, its member-states and its financial institutions (particularly the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) for an external support package. As most of these funds were taken from existing programmes, the Commission vowed to boost development aid in the EU’s next long-term budget, the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2021-27, as well as making sure that the newly created recovery fund devoted some money to external action.

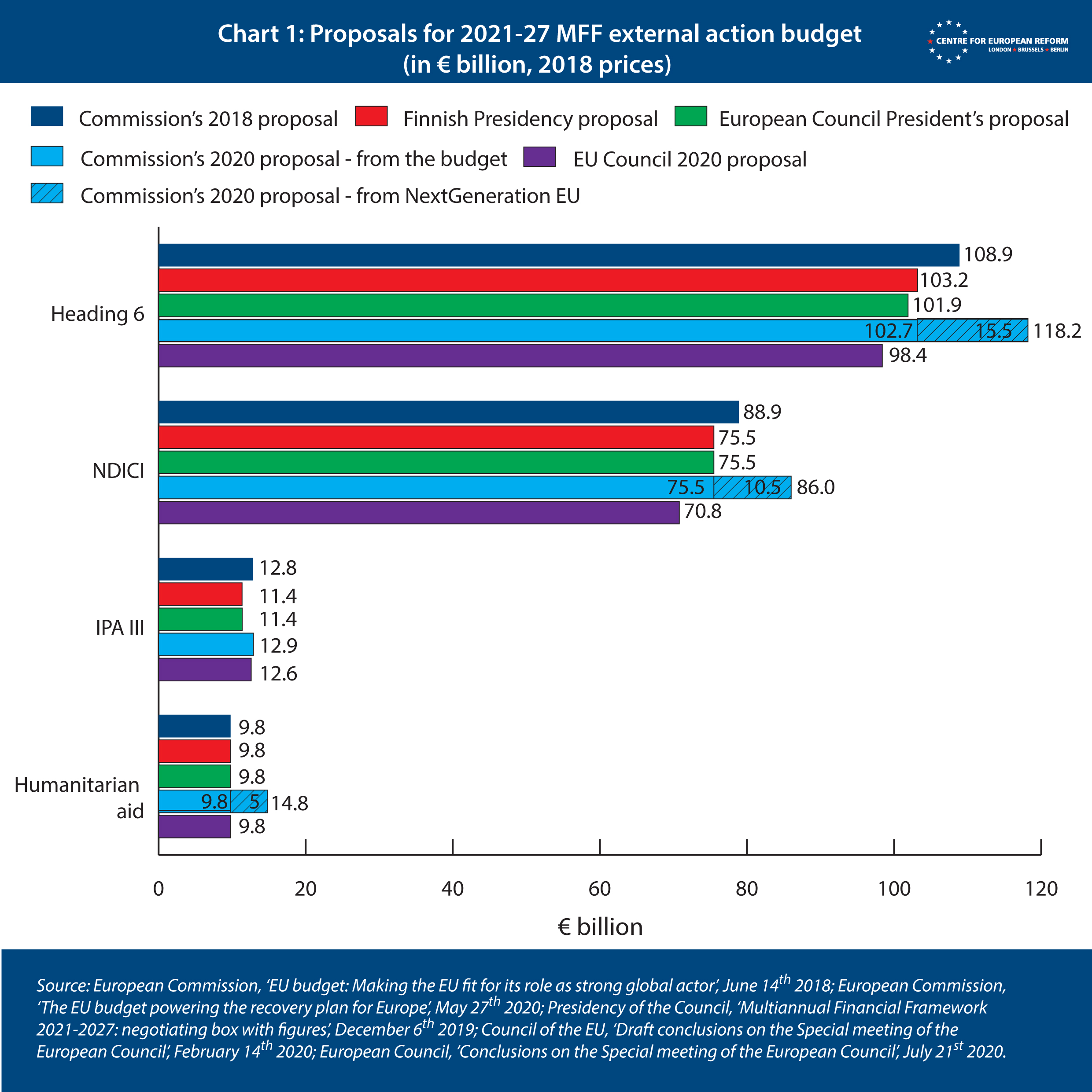

Although the July 17th-21st European Council meeting ended with an agreement on the overall budget, there were massive cuts to foreign aid under Heading 6 (‘Neighbourhood and the World’). Only €98.4 billion (or 9.2 per cent) of the €1.074 trillion budget for 2021-27 is allocated for external spending. Despite the Commission’s initial pitch to increase that budget substantially, this is little more than the estimated €96.9 billion in the 2014-20 period.

The EU’s new main aid tool – the Neighbourhood, Development and International Co-operation Instrument (NDICI) – received a meagre €70.8 billion. This is far from what the Commission envisaged before the pandemic broke out (see chart 1). Only funding for the EU’s humanitarian aid and its pre-accession assistance (‘IPA’) for the Western Balkans and Turkey remained at the level the Commission initially proposed in 2018.

As the coronavirus pandemic spread across the world, the EU soon realised that unless it offered prompt support to poorer countries beyond Europe, the economic, security and humanitarian price of the crisis would be much higher for the Union. Since April 2020, the European Commission has managed to raise almost €36 billion from the EU, its member-states and its financial institutions (particularly the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) for an external support package. As most of these funds were taken from existing programmes, the Commission vowed to boost development aid in the EU’s next long-term budget, the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2021-27, as well as making sure that the newly created recovery fund devoted some money to external action.

Although the July 17th-21st European Council meeting ended with an agreement on the overall budget, there were massive cuts to foreign aid under Heading 6 (‘Neighbourhood and the World’). Only €98.4 billion (or 9.2 per cent) of the €1.074 trillion budget for 2021-27 is allocated for external spending. Despite the Commission’s initial pitch to increase that budget substantially, this is little more than the estimated €96.9 billion in the 2014-20 period.

The EU’s new main aid tool – the Neighbourhood, Development and International Co-operation Instrument (NDICI) – received a meagre €70.8 billion. This is far from what the Commission envisaged before the pandemic broke out (see chart 1). Only funding for the EU’s humanitarian aid and its pre-accession assistance (‘IPA’) for the Western Balkans and Turkey remained at the level the Commission initially proposed in 2018.

The €750 billion recovery fund also does not contain any development aid, despite earlier plans to allocate €15.5 billion from it for budgetary guarantees for external investment and for humanitarian action. But, perhaps most importantly, the way the EU will disburse money in the future will change, too.

New structure for the EU’s development spending

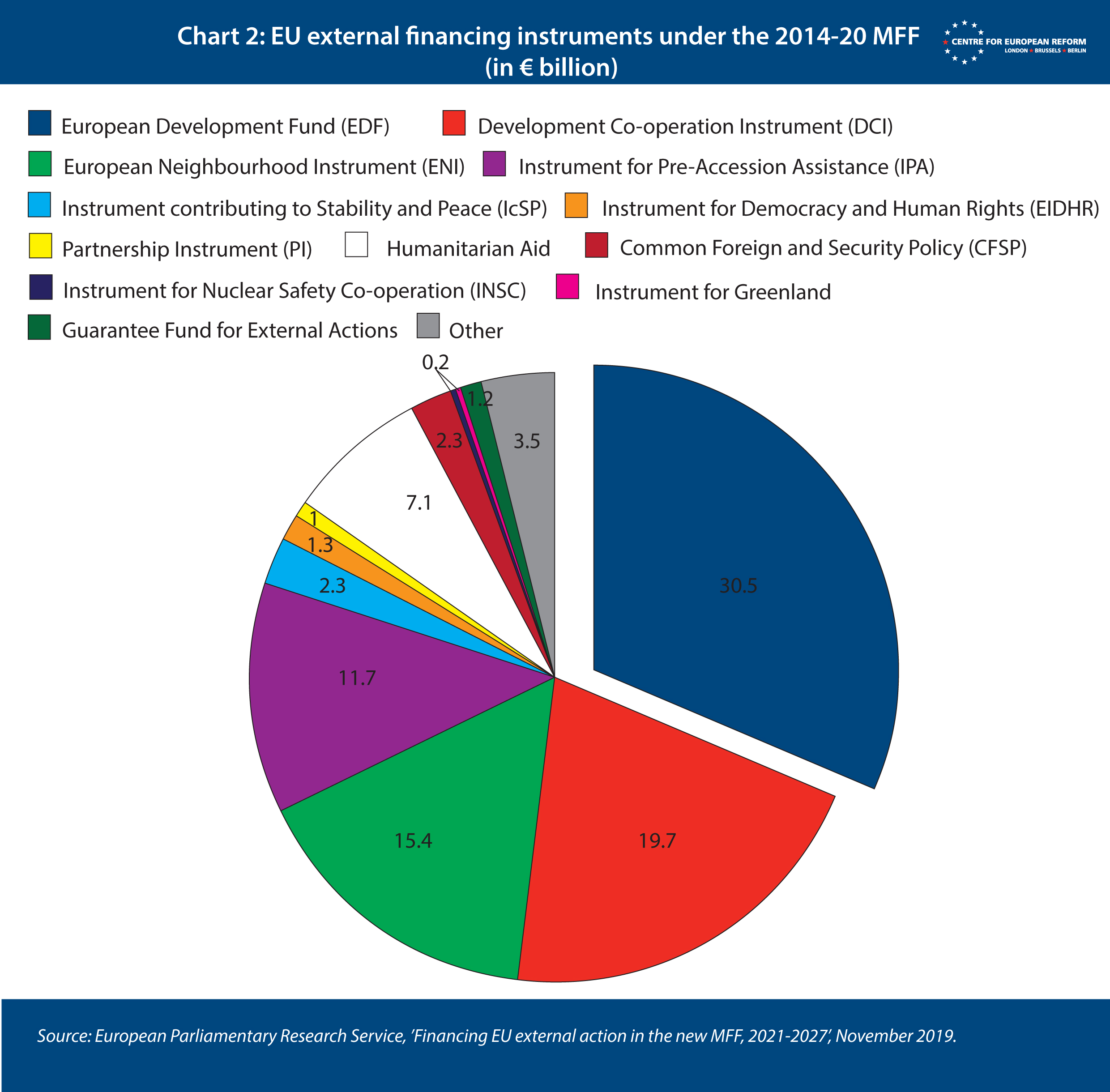

The good news is that the Commission should now be able to send money to developing countries using easier, less rigid procedures. Under the current MFF, development-related expenditure is financed from many different instruments (see chart 2). The largest is an extra-budgetary European Development Fund (EDF) for assistance to most of the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries, which member-states are financing according to a different cost-sharing ‘key’ from the regular budget. Developing countries in other regions, as well as the Union’s thematic priorities, are financed from EU budgetary instruments.

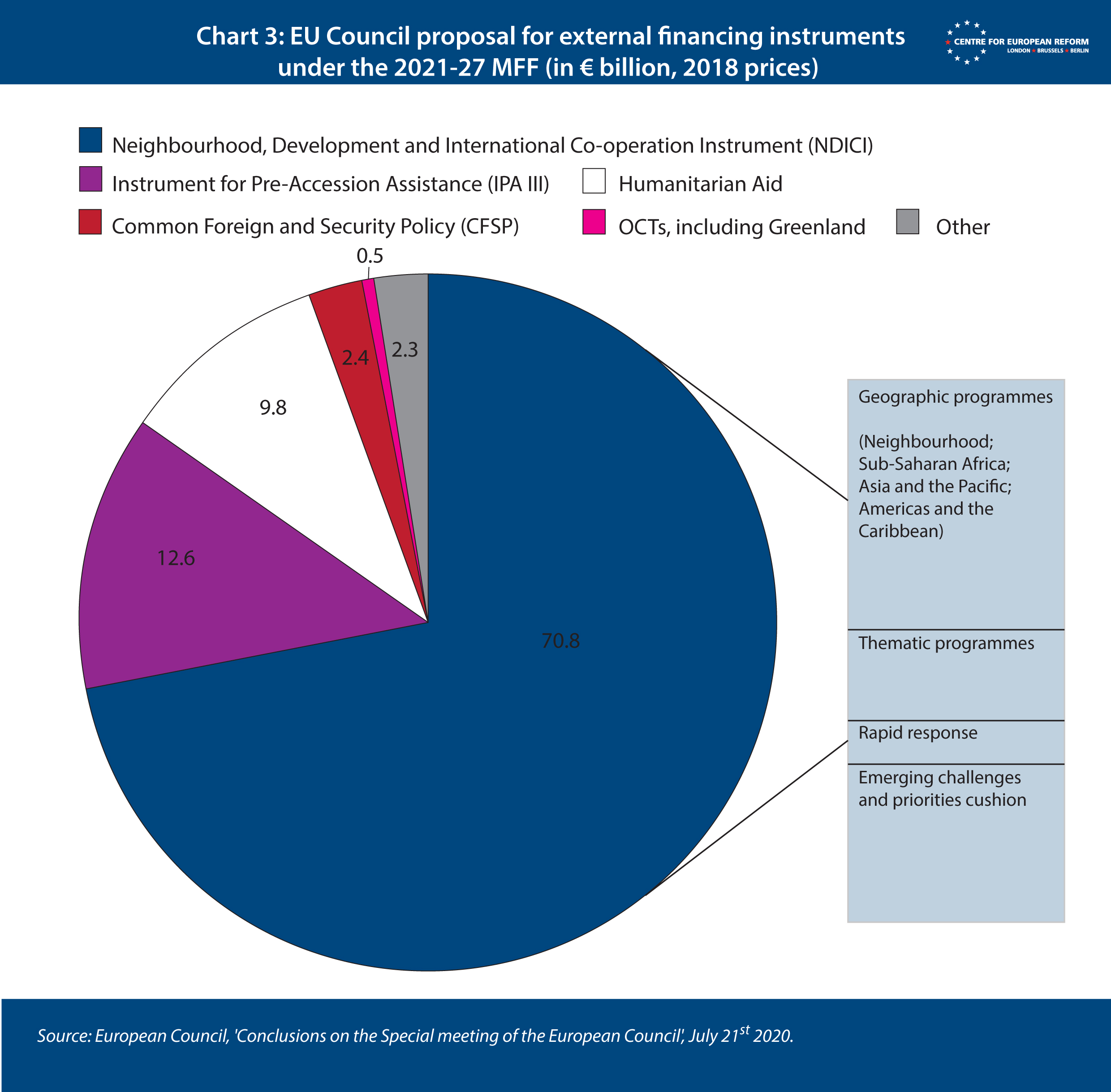

In the 2021-27 MFF, most existing instruments, including the EDF, will be merged into the NDICI. The NDICI will work on the basis of three pillars: the first based on geographical preferences; a second looking to fund specific projects in the areas of human rights and democracy, civil society, stability and peace; and a third so-called rapid response pillar to complement humanitarian aid. The last will be used for EU intervention in case of a conflict or a crisis when there is a need for rapid action in pursuit of the EU’s foreign policy needs. But the NDICI’s most important new feature, particularly because no EU aid fund has had it before, is a ‘flexibility cushion’ – a reserve to address unforeseen needs, which will not be programmed in advance. The reorganisation of the EU’s aid machinery reflects the bloc’s far-reaching ambitions to use development funds to help manage migration flows, boost the continent’s security, tacklе climate change and support human rights across the world. It also reflects the EU’s geographical priorities in Sub-Saharan Africa, the neighbourhood and the Western Balkans.

With the new structure of external action budget, the EU will link its development and foreign policy objectives even more closely. Many observers worry that the EU’s security and migration concerns might trump its commitment to poverty eradication and sustainable development. With a single, more flexible instrument, poor countries of limited strategic significance to the EU might end up worse off. However, the Commission’s proposal for the NDICI regulation reiterates the EU’s pledge that at least 92 per cent of the spending should count as official development assistance (ODA), meaning that it should specifically target the economic development and welfare of developing countries. If the Commission can maintain this commitment, the reform will bring several crucial advantages.

The new structure of the EU's aid budget will bring several crucial advantages for dealing with unpredictable and complex global challenges, and will increase the transparency of the EU aid.

First, the new structure will give the Union more room to mobilise emergency funds to deal with unpredictable and complex global challenges. In the past, the EU addressed multiple crises by setting up ad hoc instruments such as trust funds. But that left mechanisms with multi-billion euro budgets (for instance, the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa or the Facility for Refugees in Turkey) with very little, if any, democratic accountability. The rapid response pillar and ‘flexibility cushion’ should reduce the need for such ad-hoc instruments. But the NDICI regulation – which is currently not very specific about the oversight mechanisms − must set out a clear procedure and grounds for tapping these funds, or the accountability problem will persist. The new external action budget will also allow uncommitted funds in various programmes from one year to be spent in the next one, or to be re-allocated from one project or programme to another in subsequent years, which is currently impossible.

Second, by bringing several external action instruments together and thus simplifying administrative and financial procedures, the Commission will reduce bureaucracy. The reform should eliminate overlaps and artificial boundaries between EU instruments. It will also help to simplify the oversight system, by allowing the European Parliament, the Council, the Court of Auditors and other audit authorities to have a single overview of the Union’s external expenditure, instead of assessing the Union’s multiple funds separately, as is the case now. Most importantly, it will increase the transparency of the Commission’s development expenditure and enhance the European Parliament’s role in overseeing it.

Third, streamlining the EU’s aid budgets will increase the Union’s visibility in partner countries and help the EU advance its strategic agenda. The EU is the world’s largest donor, but this is seldom reflected in the EU’s influence in third countries, especially vis-à-vis the US and China. Increasing the bloc’s political weight in developing countries is particularly relevant now that the Commission is preparing a new partnership with Africa, which the EU plans to endorse at the EU-African Union summit in October 2020. The EU is currently negotiating this new regional partnership in parallel with the talks on the successor to the Cotonou Agreement, which governs relations between the EU and 78 ACP countries.

Finally, the EU will put increasing emphasis on leveraging private investment to generate growth in developing countries, gradually moving away from traditional grant-based assistance in the next MFF. The reform will integrate all the EU’s regional investment funds into one, the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+), with world-wide coverage. EFSD+ should connect the EU’s development, economic and political priorities more closely – provided that the EU, member-states and development banks can agree on reform of European development finance architecture.

Punching below its weight on aid volumes

Despite these positive reforms, the external action heading suffered a major cut, making it one of the budget’s biggest losers. Out of a total reduction of €60.3 billion from the Commission’s MFF proposal, external action accounted for 17 per cent. This seems to suggest that the area remains a secondary priority for most member-states.

But at a time when other countries, above all China, are leveraging their more modest aid to gain political influence, the EU should not lower its level of ambition. A significant development budget is crucial for advancing the EU’s interests in priority countries and strategic regions, so the cuts go against European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s declared aim of leading a “geopolitical Commission”. A larger external budget would help the EU to fulfil its global ambitions on issues like the green economy and digitalisation, at a time when its agenda in many third countries is diverging from that of other donors and lenders including China, Russia and even the United States.

At a time when other countries, above all China, are leveraging their more modest aid to gain political influence, the EU should not lower its level of ambition.

While the suggested level of external spending for the next MFF is greater than the current one in nominal terms, it does not take into account the need to address new challenges facing low- and middle-income countries because of COVID-19. Recent reports indicate that the coronavirus pandemic threatens decades of progress on global poverty reduction, healthcare and education. Developing countries are hit hardest not only by the direct impact of the health crisis and domestic lockdowns, but also by lost remittances and tourism revenues, lower demand for their exports and disruption of global supply chains. In spite of the Commission’s initial aspirations, EU development funding in the next MFF is unlikely to be transformative for recipient countries, but it will be vital nonetheless.

Looking ahead

The MFF deal agreed by European leaders in July now needs to be approved by the European Parliament. MEPs lamented cuts to the budgets of many instruments, including the NDICI – and in a resolution threatened to block the MFF. But the Parliament disagrees with national capitals over many aspects of the MFF that it regards as more critical than the external action budget. So it will probably focus its efforts on fighting the European Council’s proposals on issues such as the governance of the recovery fund and rule of law conditionality. While there is little room for the external action fund to be increased during forthcoming negotiations, however, some shuffling between instruments and within the NDICI may still be possible.

Even if the numbers are unlikely to change much, the EU can still make development assistance more effective. For that, the institutions should take into account three main issues.

First, while the EU is trying to pursue more interest-driven external policies, it should still put poverty reduction and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the core of its efforts. In her speech at the UN in May 2020, Ursula von der Leyen proposed a global recovery initiative that would link investment and debt relief to the SDGs. But that pledge should start with the EU’s own development programmes.

While the EU is trying to pursue more interest-driven external policies, it should still put poverty reduction and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals at the core of its effort.

The NDICI proposal rightly earmarks spending for certain development goals, such as 20 per cent on human development and social inclusion. Those targets, however, do not safeguard spending on the least developed countries and most vulnerable population categories, particularly refugees. While the Commission says that the countries most in need will be given priority, spending on the poorest countries should be earmarked rather than expressed only in the form of a political commitment. In line with emerging priorities, the EU should dedicate more resources to the development of the public health sector and disease surveillance capabilities in low-income countries, particularly in Africa and the neighbourhood.

Second, as the budget for traditional assistance will be smaller, the EU’s role in leveraging private investment will be increasingly important in supporting its development objectives. The Commission should therefore set targets for how much of the investment backed by the EFSD+ should be committed to the EU’s priority areas and regions, particularly to fragile countries. Job creation, private sector development, climate change, gender equality, digitalisation and health services are of particular importance.

Third, at a time of scarce resources, the EU should continue to pursue greater co-ordination of development efforts with like-minded countries, both in terms of emergency response and longer-term development strategy. In its 2018 reform proposal, the Commission indicated that joint programming by the EU and member-states, with scope for other donors to join, would be its preferred approach to pooling efforts. While some countries, such as Norway or Switzerland, have found that pooling their efforts with the EU was a cost-effective way of delivering aid to those in need, big donors among non-EU G7 members prefer to follow a separate course. The UK may not be keen to take part in joint programming with the EU, once current projects terminate. It is crucial that the EU promotes at least informal co-ordination with its Western partners on the ground in third countries to avoid duplication of their assistance.

European development policy has been going through a gradual process of evolution for as long the Union itself has been changing. Despite the disappointing size of the new aid budget in the European Council’s proposal, the current reform presents a chance to make the EU a more visible and influential player on the global stage. Efficiency and coherence of the Union’s action are the critical requirements.

Khrystyna Parandii was the 2019-20 Clara Marina O’Donnell Fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment