On Europe, Labour should reconsider its 'red chains'

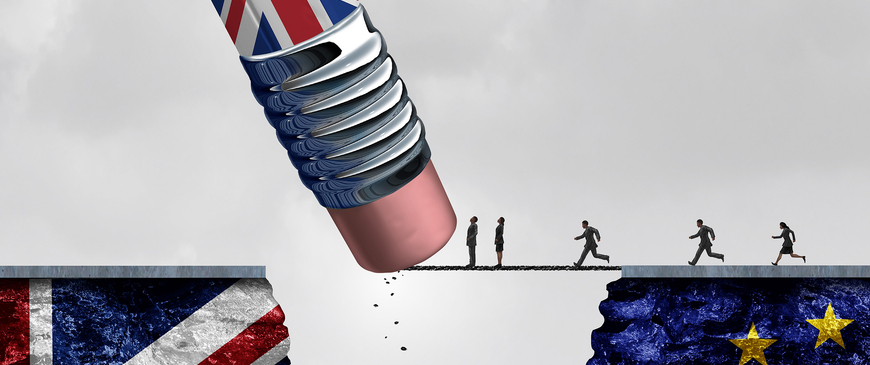

Labour’s reset with the EU will fail to deliver a significant boost to economic growth. A fundamental refashioning of the EU-UK relationship would require Labour to think again about freedom of movement.

Generals, it is said, are always preparing to fight the last war. Similarly, British politicians are always preparing to confront the issues that dominated British politics around the Brexit referendum for fear of unleashing a populist backlash. But this leaves them unable to confront the issues of tomorrow. Labour’s red lines have hamstrung the government’s approach to Europe, leaving it with few options to reverse the economic damage that Brexit has wrought. The fear of revisiting freedom of movement has been particularly damaging.

Labour’s red lines have hamstrung the government’s approach to Europe, leaving it with few options to reverse the economic damage that Brexit has wrought.

Economic growth is the British government’s number one priority, according to Prime Minister Keir Starmer. British growth has been lacklustre since the financial crisis and slower than in the EU, despite the UK being relatively unaffected by the intervening euro crisis. Juxtaposed with the US, the difference is even starker. The Labour government has shown that it is capable of being hard-nosed and courageous to promote growth, for example in tackling long-standing problems such as the need for planning reform. And, since the government has no money, it has also shown willingness to make tough and unpopular choices that risk angering its own base, such as cutting development aid and winter fuel subsidies for the elderly, whilst increasing defence spending.

The search for economic growth has extended to seeking closer ties with the European Union. This makes sense, as Brexit – by disrupting trade and economic ties with the EU – is a significant driver of British economic underperformance. Calculating the counterfactual size that the British economy would have had without Brexit is a difficult exercise, but the best estimates from such counterfactual analyses are in the range of 4-5 per cent, depending on whether you believe the government Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) or the Centre for European Reform.

Going by the OBR estimate of 4 per cent, Brexit has cost the UK economy £100 billion every single year, even with the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) in place. It is exceedingly rare for a single policy intervention to have such a large impact: in comparison, the benefits of a theoretical free trade agreement with the US would be roughly half a percent of GDP, or about £13 billion of economic activity per year.

But when it comes to Europe, the government shows little of the courage it has displayed in other areas. The Labour election manifesto had three red lines: no customs union, no single market membership and no freedom of movement. Likewise, in terms of concrete progress on trade relations, Labour only really made three promises: a veterinary agreement on sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regulations to facilitate trade in foodstuffs, a mutual recognition agreement for professional qualifications, and facilitating touring for cultural workers. The CER analysed these proposals in depth last year. They do not amount to a fundamental reset – they are, rather, a cautious, gradual but shallow deepening of relations, building on the TCA.

But Labour laid down its red lines and commitments a year ago and the world has changed dramatically since then. The Brexit referendum changed UK politics, but the second Trump administration has changed global politics. Trump’s tariff policies have upended the already threadbare international legal order for trade, raised new and unexpected barriers for UK exports, in particular vehicles, and escalated US-China trade tensions. Yet British trade policy has continued largely as if nothing has changed.

The Brexit referendum changed UK politics, but the second Trump administration has changed global politics.

For some UK sectors, such as the car industry, the situation is now critical, as US tariffs compound its already difficult position after Brexit. Even after the recent UK-US trade deal, British car exports still face a tariff of 10 per cent. It is no longer tenable for the UK’s European policy to be shaped by the Brexit years. UK economic security depends on having reliable partners. If the US is no longer a reliable partner, the UK will need closer and very different ties with its other friends, allies and neighbours than was envisaged even a year ago. The EU’s rule-bound and legalistic approach, often derided in the Brexit debate, will perhaps be regarded with newfound appreciation when the alternatives are the power politics of Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping.

For the UK, the fact that a reset was needed so soon after the TCA was implemented in 2020 was already an explicit admission that the agreement had failed to meet British needs. The UK, having amputated an economic relationship developed through four decades of EU membership, is suffering from the phantom pain of severed ties. But for UK businesses deeply integrated into a European supply chain or used to unfettered access to a continent-wide market, the UK reset proposals offer scant improvement. The economic impact would be small – most likely around 0.3 per cent of GDP. The bulk of that would come from youth mobility, as temporary workers would boost the UK economy. By global standards the TCA is an ambitious agreement, but even with Labour’s proposed improvements, it would amount to a better pair of crutches, not the prosthetics needed to get UK-EU trade marching again.

The UK, having amputated an economic relationship developed through four decades of EU membership, is suffering from the phantom pain of severed ties.

The inadequacy of the UK proposals is perhaps best demonstrated by its approach to product regulation. Since the UK does not want single market membership – one of the red lines – it has not sought to align itself with EU rules on product regulation, which is a catch-all that designates the different technical and safety standards needed to ensure appropriate quality for goods. Initially, the UK tried to impose its own product regulation. But since the UK is not a large enough market to force firms to meet its unique standards, this risked causing higher prices and making some products unavailable. The UK has thus de facto been forced to recognise the EU’s standards, a process that began under the Sunak government. Labour is taking this one step further by passing the Product Regulation and Metrology Bill, which would allow ministers to change UK product rules to maintain alignment with the EU, without primary legislation.

This means that instead of publicly committing to alignment with EU product regulation, the UK will de facto maintain essentially the same alignment through a series of opaque and unpredictable ministerial decisions. These will not give investors and businesses the predictability they need, but will allow the government to avoid infringing on its red line of no single market membership. Having publicly committed to respecting the result of the Brexit referendum, the government has thus found a suboptimal and complicated solution that respects the letter of its manifesto commitment while subverting its spirit. From a public policy perspective, it would be far better to let the sunlight in and make transparent decisions, either through a public commitment to unilateral alignment with EU rules, or – even better – through a broader agreement with the EU.

The May 19th UK-EU summit will deliver results. For example, the two parties will agree to start work on the veterinary agreement promised by Labour. There is also hope for closer co-operation on energy and carbon emissions. In return, the EU will probably get some concessions on fishing as well as a youth mobility scheme similar to what the UK has already granted other partners. These are welcome steps, but they also represent a lack of ambition due to the constraints the UK government has imposed on itself. To truly rekindle growth, the UK needs a more ambitious reset of its relationship with Europe. Such ambition will have to contend with the UK’s three red lines.

To truly rekindle growth, the UK needs a more ambitious reset of its relationship with Europe.

Of the three red lines, rejoining the customs union seems like the most obvious way to further minimise trade barriers. But it is also the least likely to be reconsidered. For a start, the UK cannot join the EU customs union on the same footing as, say, France or Germany – the EU treaties reserve that status for member-states. In practice, there would have to be a separate UK-EU customs union, similar to the one Turkey has with the EU. Such an arrangement would substantially cut paperwork at the border but not eliminate it. Goods would have to be accompanied by a movement certificate, a document proving that they are free to circulate. Nor would a separate customs union make the UK part of the EU's Value-Added Tax (VAT) area as it was before, and it would also be incompatible with all the trade agreements that the UK has negotiated with other countries post-Brexit. Advocates of a customs union tend to underestimate the political difficulties, even if the practical upside is clear.

The second red line – no single market membership – is poorly defined, as there is no single market membership club. Norway and Iceland come closest through the European Economic Area (EEA), with virtually full access to the single market for goods and services. But even for those countries, there are limited exceptions, for instance in seafood and agriculture. Switzerland similarly has single market access for most goods, but with a far closer institutional and legal relationship with the EU than the UK has right now. The UK is essentially seeking single market access for foodstuffs, while unilaterally aligning on standards for most other products. The UK conceding on the principle of accepting EU court oversight and dynamic alignment on veterinary rules blurs that red line: it is difficult to see a rationale for agreeing to one set of principles for food, but not for other sectors like chemicals or medical devices.

This leaves freedom of movement, which unfortunately has become taboo in British politics, as immigration is widely blamed for the Brexit vote. The politics of budging on freedom of movement would be tricky. Labour fears being soft on immigration lest it loses voters to Reform UK. Britain’s inability to stem the flow of migrants crossing the Channel in small boats raises fears that Britain is unable to control its borders. And high rates of immigration coupled with Britain’s inability to build sufficient housing creates the perception that migrants compete with Britons for scarce resources. Instead of embracing immigration, the government has therefore pledged to restrict it further.

The politics of budging on freedom of movement would be tricky. Labour fears being soft on immigration lest it loses voters to Reform UK.

But that will not change the need to attract world-class talent for the services sector that fuels the UK economy, as well as carers to meet the needs of an aging population and construction workers to build more housing. And rhetoric that does not match economic and political reality risks further undermining trust in the establishment among Reform voters, while leaving Labour vulnerable to losing voters on its other flank to the Greens and the Liberal Democrats.

Labour's jitters about another wave of immigration from Central and Eastern Europe are also overblown – that moment has passed. The ‘new’ EU member-states are increasingly wealthy, with low rates of unemployment and increasing labour shortages as a result of aging and shrinking work forces; they are instead themselves becoming countries of immigration, not emigration. Nor is it clear that this is now a priority for Britons: an astonishing 68 per cent of British voters would be happy to accept freedom of movement in return for single market access. The Westminster political consensus has not kept pace with the British people in this respect, for fear of the Brexit voter. But the British public has historically been open to immigration – 2016 was an aberration in that respect, coming right after the Syrian refugee crisis and the influx of immigrants after the 2004 EU expansion. Although immigration is a top concern for the UK public, the worry is primarily illegal migration in small boats, not people coming to work.

If the fear is losing control over immigration from Europe, the UK should require EU immigrants to register with the authorities and try to negotiate with Brussels the option of safeguard measures if immigration causes societal problems. Such a safeguard exists, for example, in the EEA agreement, though it has never been used. And since accepting freedom of movement would also enable the UK to rejoin the Dublin convention that allows returning asylum seekers to European countries, the UK government will be able to argue that freedom of movement would help address illegal immigration. For this to work, the government would have to level with the British public about both the need for legal immigration and the trade-offs involved, and to have faith that the British public are as receptive to arguments as the polls suggest.

Conceding on freedom of movement would allow for a true reset with a ready-made model based on the Swiss approach. This would allow freedom of movement for individuals in both directions and single market access for goods, while largely retaining UK regulatory autonomy on services. Such an approach is both realistic and would make a substantial contribution to UK GDP: 1-1.5 per cent by one estimate.

The relatively modest economic benefits that can be expected from the May summit are worth having. But they will not prove enough in the long run, either in terms of delivering economic growth or in terms of settling EU-UK relations. Labour should use the period after the summit to open a proper and public debate about the UK’s future role in Europe. That debate should be free of red lines designed to satisfy what politicians deem to be the primary motives of Leave voters. The objective should not be to ‘make Brexit work’; it will never work. The future goal of British policy cannot forever be to satisfy the purported and unstated motivations behind a decade-old referendum result. It should be to advance what is best for the country – whose number one priority is, according to its own government, economic growth. And if that is the goal, the focus should be on pragmatic solutions, not red lines.

Aslak Berg is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment