How to reduce dependence on Russian gas

At the European Summit on March 20th and 21st, government leaders were supposed to agree climate and energy targets for 2030. Instead, they discussed Crimea, Ukraine and Russia. Leaders were right to postpone discussion of the targets, but wrong to postpone action on reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian gas.

Russia supplies around a third of the EU’s gas. So the Union is to an extent dependent on Moscow – as it discovered when the Russians turned off the gas flow though Ukraine in 2009. But the Kremlin is, to a greater extent, dependent on revenue from oil, gas and coal exports – above all to the EU. Indeed, over half of the Russian government’s revenue comes from the sale of fossil fuels: 19 per cent each from gas and oil and 14 per cent from coal. The EU summit conclusions did refer to the need to diversify sources of gas, and asked the European Commission to prepare a report on this. That approach lacks the urgency which the situation in Ukraine demands. If EU leaders want to impose sanctions on Russia which may change its behaviour, rather than simply slapping Putin’s wrist, they should reduce purchases of Russian energy as far and fast as possible. To do that, they must develop alternative energy sources. That would cost money, but deliver major energy security, foreign policy and climate benefits.

The Swedish and Danish foreign ministers, Carl Bildt and Martin Lidegaard, have emphasised the importance of energy in responding to Russia’s invasion of Crimea. In March they wrote in European Voice that the EU must improve its energy efficiency, develop infrastructure to import fossil fuels from countries other than Russia, and increase alternative energy sources such as renewables. Swedish and Danish ministers are well placed to make these points: Sweden gets more of its energy from renewables than any other member-state, while Denmark is the only country to have set out plans to become 100 per cent reliant on renewables (by 2050). Poland buys nearly 90 per cent of its imported gas from Russia. So Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski has shown courage in leading the calls for reducing energy dependence on Moscow (though Poland uses coal for most of its energy needs).

Europe’s post-Crimea energy strategy should focus on five strands:

* energy efficiency;

* alternative sources of gas;

* renewable energy;

* coal and gas with carbon capture and storage (CCS);

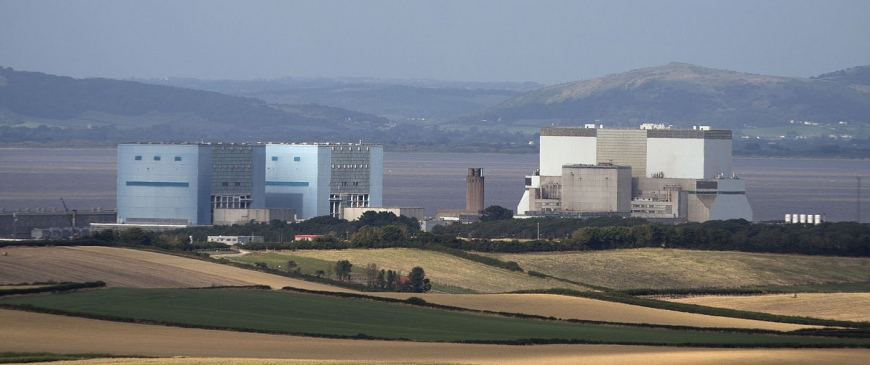

* nuclear power.

Greater energy efficiency is the goal that could be achieved most quickly. A rapid and ambitious programme of retrofitting double glazing and insulation to existing buildings, Europe-wide, could reduce energy demand for heating. It would also create thousands of new jobs. Less rapid but equally effective would be a major programme to upgrade and expand district heating: networks which transport heat from power stations or other combustion plants to homes and commercial buildings. District heating is widespread in Central and Eastern Europe, but most of it is old and inefficient, losing up to half of the heat during transport. (District heating networks in Scandinavia, by contrast, lose less than 10 per cent of the heat.) On alternative sources of gas, the quickest measure would be to expand the EU’s capacity to import liquefied natural gas (LNG). The Commission should stress, in all its contacts with the US government, the strategic advantages of the US exporting LNG. But increased imports of LNG are not dependent solely on successful trade negotiations with the USA; such gas is available from other non-Russian sources, notably Qatar. Greater use of LNG will require new infrastructure and any state that has a coast can develop LNG facilities. The Commission should give priority to less wealthy member-states that are highly dependent on Russian gas: the Baltic states, Bulgaria and Poland. This would not improve Europe’s overall energy security, but would help those countries highly dependent on Russian gas: the five countries mentioned above plus the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary and Slovakia.

To improve EU energy security overall, EU institutions should do all they can to ensure that new pipelines are constructed to transport non-Russian gas from the Caspian Sea to Europe. Contracts have been signed for a Trans-Anatolian pipeline from Azerbaijan to the Mediterranean coast of Turkey, and a Trans-Adriatic pipeline from there to Italy. But construction has yet to begin. This pipeline would reduce EU dependence on Moscow, unlike Gazprom’s South Stream, which would simply be an alternative way of transporting Russian gas to the EU (while avoiding Ukraine).

Indigenous shale gas is another source of non-Russian gas. Governments which have banned fracking, either formally (France and Bulgaria) or informally (Germany) should now reverse this position. Renewable gas, which can be created from food and farm waste, manure and sewage, should also be expanded as much and as fast as possible. This is already widely used in Germany and Austria. Using these wastes to produce renewable gas would improve water quality, because the residue can be used as fertiliser rather than being discharged into rivers or seas. Greater use of renewable gas would help achieve climate policy objectives, as well as greater energy security. Renewable electricity must also be expanded. This would reduce the need to use gas for electricity generation, and also for heating (since heat can be provided in domestic and commercial buildings by electricity rather than by gas). The Commission could co-ordinate national subsidy schemes for renewables more closely, as this would cut administration costs for developers and reduce regulatory risk, so cutting the cost of capital. And all European institutions must work together to expand and improve the electricity grid, with a focus on the Baltic, Mediterranean and North Seas, and around the Pyrenees.

What role should coal play in future energy policy? Here the need for energy security conflicts with the need for climate protection. A quarter of the coal which the EU imports comes from Russia. The EU could survive easily without Russian coal, by mining more within its own borders and by importing more from other countries. However, coal is extremely polluting. Burning coal can cause high levels of toxic air pollution, damaging human health and harming the environment. EU rules have been effective in reducing toxic pollution from coal combustion. Coal generation also emits high levels of greenhouse gases – about twice as much pollution per unit of electricity as gas combustion does. Yet technology exists to cut greenhouse gases from coal combustion. CCS has been demonstrated at small scale, but not yet at large scale. The EU is falling behind Australia, Canada, China and USA in its attempt to roll it out.

CCS is not popular with the German public. But it is less unpopular than nuclear power. Before the 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan, Chancellor Angela Merkel said that low-carbon bridge technologies were necessary, to protect the climate while the world moves from fossil fuels to renewables. She was right. The transition to renewables will take at least half a century – probably longer. Gas is less bad for the climate than coal is, but not low-carbon enough to prevent dangerous climate change unless combined with CCS. Merkel’s post-Fukushima energy policy sets out an end point – total reliance on renewables – but pays no attention to what happens during the transition. The result – as statistics from Germany demonstrate – is increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Even the German desire for energy security and reduced dependence on Russian gas seems unlikely to persuade most Germans to reconsider nuclear power. There is more chance that they will reconsider CCS. But the most likely outcome is that Germany will become even more willing to burn coal without CCS. This would seriously compromise EU climate action. To avoid this outcome, EU institutions should set an emissions performance standard to regulate the maximum amount of greenhouse gas that can be emitted per unit of electricity generated. This would ban coal without CCS. However, demonstration and deployment of CCS will require subsidy. Renewables and nuclear power will also require some form of financial support. All these technologies are needed for climate protection. They could also help make Europe’s response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea more credible.

Reduced reliance on Russian energy sources, and increase in resilience in the event of a supply cut off, should be central elements in a long-term re-orientation of EU energy policy. European institutions and member-states should implement the five-strand strategy outlined above: use energy much more efficiently; develop all alternative gas sources; maximise renewable energy; demonstrate and deploy CCS; and build new nuclear power stations. This strategy will not be cheap. But the economic, security and climate action advantages will justify the cost. IMF managing director Christine Lagarde is right to say that climate change is “by far the greatest economic threat of the 21st century”.

Stephen Tindale is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.