No denial: How NATO can deter a creeping Russian threat

Russia’s Vladimir Putin disregards arms control agreements, places sophisticated weapons close to NATO’s borders, and deliberately sows uncertainty over his intentions. He is creating no-go areas in parts of Eastern Europe, making NATO allies nervous and challenging Europe’s security order. But NATO can still deter him.

#Putin has created no-go areas in parts of Eastern Europe, making #NATO allies nervous.

No all-out war, no less of a threat

On February 2nd 2016, US defence secretary Ashton Carter announced that he intends to quadruple funds to promote European security. He said that the US is taking “a strong and balanced approach to deter Russian aggression, and we haven't had to worry about this for 25 years.” What is going on?

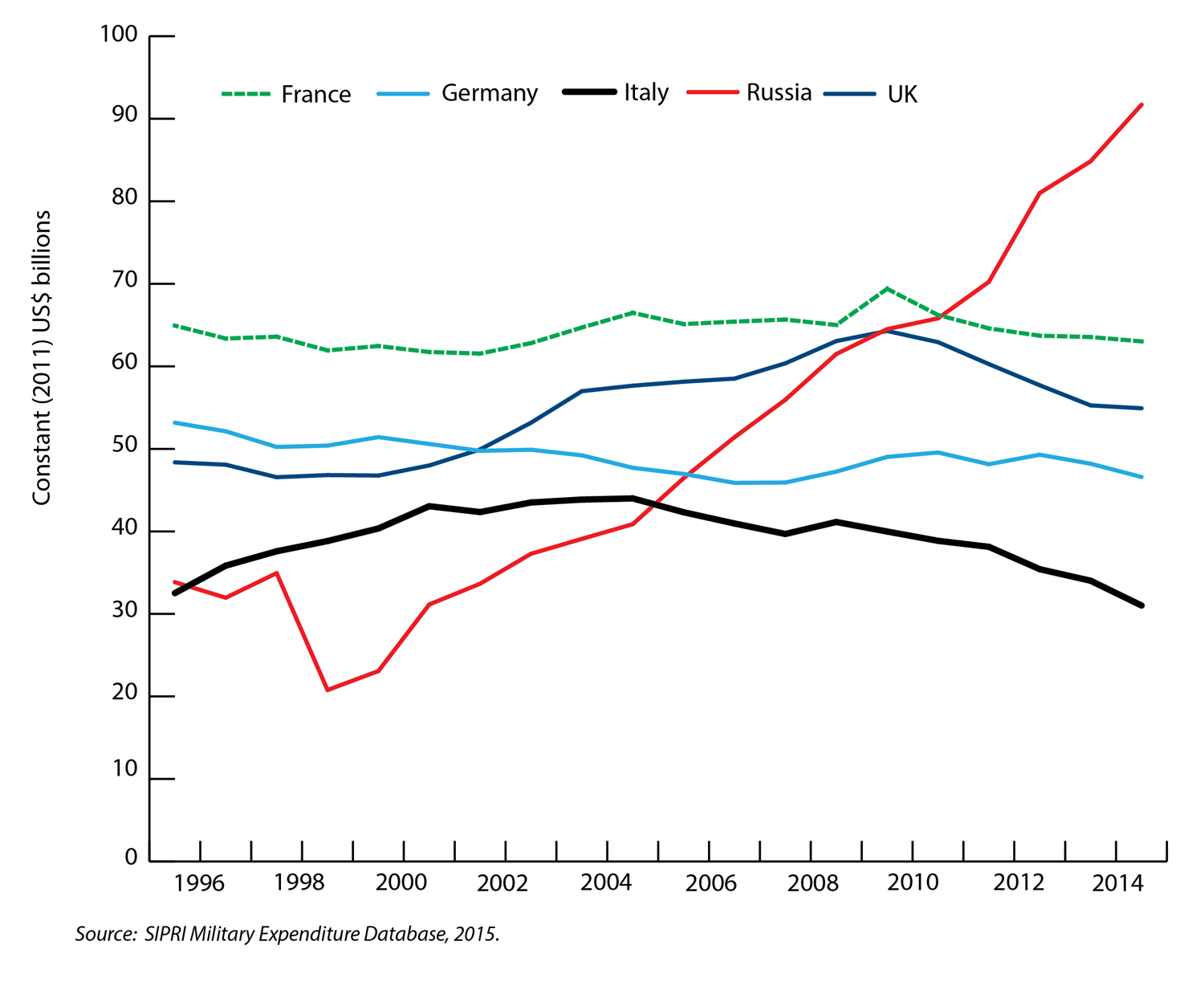

Rest assured, if it came to a shooting war, NATO would prevail. Despite considerable increases over the past decade in Russia’s military budget, NATO’s members collectively outspend Russia around tenfold. Western forces can rely on superiority in numbers, more sophisticated technologies and myriad options to squeeze Russia economically.

But an all-out war is neither in Russia’s, nor NATO’s interest. Instead, NATO’s strategists (and those at the Pentagon) worry about something more opaque. Moscow feels surrounded by NATO, and a paranoid Russia is cause for concern. Russia’s 2014 military doctrine pointed to the perceived danger of NATO enlargement, the alliance’s missile defence system and “the establishment in states bordering Russia of regimes whose policies threaten Russian interests” ‒ a veiled reference to changes of government in Ukraine and Georgia. In response, Putin is trying to push the West out of a region he considers Russia’s ‘near abroad’.

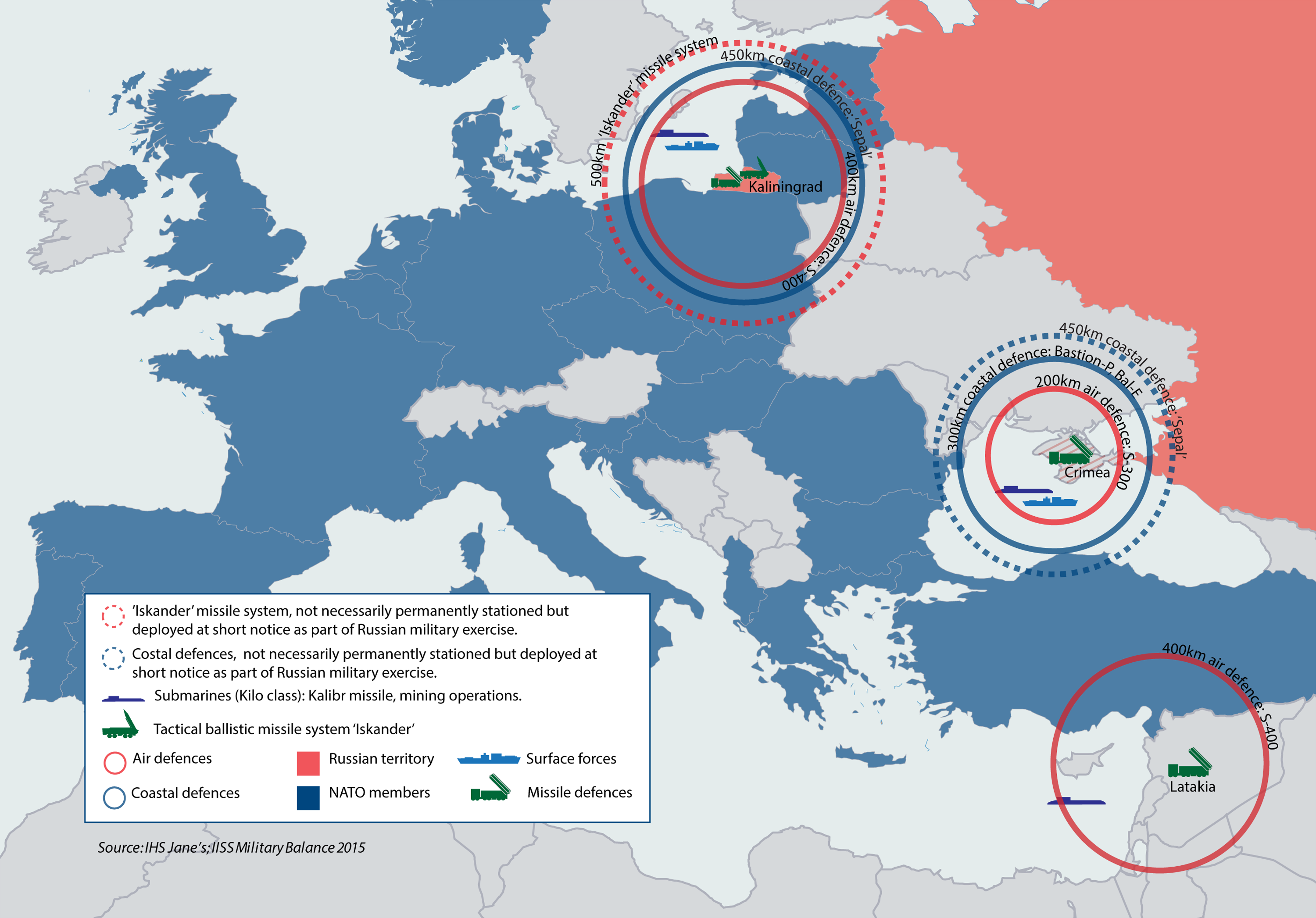

The ‘near abroad’ stretches, broadly, from the Arctic down across the Baltic states, Eastern Europe and towards the Black Sea, spanning many of the former Soviet republics, and possibly any country with a sizeable Russian-speaking minority. This includes Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, but also NATO allies like Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania. Over the past year, Moscow has placed powerful weapons in strategically important locations like Crimea and Kaliningrad. The range of these weapons extends to allied territory and airspace and could threaten NATO’s maritime supply lines.

NATO has a term for Putin’s tactics: Anti-Access Area Denial (A2/AD), which refers to an adversary’s attempts to make it impossible, or very costly, for NATO to gain access to a region to help its members or other countries. It challenges NATO’s freedom of movement. A2/AD capabilities can include missile defence systems, anti-ship cruise missiles, submarines, high-readiness brigades and special forces.

A2/AD used to be jargon known only to China-watchers. By building artificial islands in contested areas of the South China Sea, and developing advanced ballistic missiles (so-called “carrier killers”) and anti-ship cruise missiles, China aims to keep the US Navy at bay and extend its influence in the Western Pacific. Russia is now doing something similar in Eastern Europe.

#A2AD used to be jargon for China-watchers - today Russian A2AD challenges #NATO in the Baltics.

In his speech on February 2nd 2016, Secretary Carter said that “[Russia and China] have developed and are continuing to advance military systems that seek to threaten our advantages in specific areas. And in some cases, they are developing weapons and ways of wars that seek to achieve their objectives rapidly, before, they hope, we can respond.”

For instance, Russia’s decision to place advanced S400 air defence missiles in Kaliningrad has extended the reach of Russian launchers into NATO airspace, challenging NATO’s control of the skies and its ability to help its Baltic members in the event of Russian hostility. These missiles could help Moscow to invade Latvia, Estonia or Lithuania, forcing the alliance to recover the Baltic states in a military campaign of a size unseen in Europe since World War II.

What is Russia up to?

Russia is sowing doubt among Western policy-makers, not only by placing state-of-the-art equipment close to NATO borders, but also by disregarding arms control treaties, testing the readiness of its forces through large, unannounced exercises, and hinting at the possible use of tactical nuclear weapons. Putin’s veiled threats and the memory of Russia’s annexation of Crimea have made Western leaders uncertain about what to do. Sowing confusion is a deliberate strategy: many of NATO’s European members are risk-averse and reluctant to use force, and they disagree on the magnitude of Russia’s threat. Russian ambiguity risks paralysing Europe.

In 2015, Russia suspended its participation in Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty meetings, which promoted military transparency and confidence between NATO and Russia following the end of the Cold War. Russia no longer provides information on its conventional forces, allows inspections or tells NATO about its military build-ups. The CFE Treaty specified limits on Russian weapons, which Russia now disregards. In spite of Russia’s economic difficulties, Putin has made investing in more modern and combat-ready forces a priority.

Putin’s reforms are showing results. In October 2015, General Frank Gorenc, commander of US Air Forces in Europe, said that Russia’s new aircraft and air-defence systems had “closed the air force gap” with NATO. That same month, Admiral Mark Ferguson, commander of US Naval Forces Europe, warned of the increasing capability of the Russian Navy. Russia has invested in new nuclear-powered attack and ballistic missile defence submarines, partly equipped with long-range cruise missiles, which could be used to close sea-lanes or disturb lines of communication. Similarly, since annexing Crimea, Russia has modernised its Black Sea Fleet – stationed in Sevastopol – shifting the Black Sea’s military balance in Moscow’s favour.

Russia has undertaken large, unannounced exercises in the Baltic and Black Sea regions. Some exercises train for large-scale war and include up to 100,000 personnel. Other so-called snap exercises are designed to demonstrate Moscow’s heightened military readiness. The Vienna Document – last updated in 2011 – obliges all signatories (which includes NATO and former Soviet states) to submit advance notification about any exercises. Moscow’s disregard for the agreement feeds speculation over its intentions.

Most of these exercises include nuclear weapons systems. During a series of war games in March 2015, Russia temporarily deployed its nuclear-capable SS-26 Iskander missiles to Kaliningrad and sent nuclear strategic bombers to Crimea. The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty requires the United States and the Soviet Union to eliminate and permanently renounce their intermediate-range ground-launched nuclear cruise missiles (GLCM). The US government in 2014 and 2015 accused Moscow of violating its obligations not to “possess, produce, or flight-test” a GLCM or its launchers. In March 2015, Putin said he was ready to put his nuclear forces on alert after the annexation of Crimea. In Russian military circles, discussions have re-emerged over the use of a ‘limited nuclear strike’ to stop a conflict from escalating.

Europe needs a strategy

The Black and Baltic Seas have already become areas where the A2/AD principle is in play, and Russia is expanding its influence in the eastern Mediterranean, and even parts of the Arctic. Russia now uses its strategic outposts in Crimea and Kaliningrad, its airbase near the Syrian city of Latakia, and its vast network of Arctic outposts to keep NATO at arm’s length.

The possibility that Russia could nibble at parts of the NATO alliance, or bully it to stay away, has arisen because Europe is increasingly vulnerable. During the Cold War, NATO’s defence strategy relied on the so-called ‘trip wire model’ – large numbers of US combat forces were based in Europe, deterring attacks from the East. Today, the US and NATO rotate small numbers of forces through Poland and the Baltics, but the measures fall short of permanent stationing. In part, this is because Western Europe does not want to antagonise Russia, and strives to uphold the NATO-Russia Founding Act. That political agreement prohibits the permanent stationing of “substantial combat forces” close to Russia. But it also commits Moscow to respect the sovereignty of other states; a principle it clearly violated in Ukraine. By failing to respond to Russia’s A2/AD challenge, NATO has emboldened Russia.

The West has also become complacent about its military superiority. European militaries need to be more combat-ready, and lack sufficient numbers of troops, and munitions. This has led to an “erosion of real combat strength” of European forces. The bulk of NATO’s muscle is in the United States and it takes a long time for NATO to deploy forces, as it depends on a lengthy consensus-seeking process.

Warsaw and beyond

A2/AD will be discussed at NATO’s Warsaw Summit in June 2016. Here are several steps the alliance should take.

First, NATO must demonstrate that it has the determination and the capabilities to defend its members. According to a recent simulation by RAND, NATO needs about seven brigades, of which three must be heavy armoured brigades, supported by airpower and other assets, to deter Russia in the Baltic. Currently, NATO is three or four brigades short and the Pentagon only plans to add one heavy armoured brigade in the region. Due to semantic sensitivities, it is unlikely that Western troops will be stationed there ‘permanently’. But the US intends to increase the number of its troops rotating through Eastern Europe ‘persistently’, and the rest of NATO should follow suit. NATO should also invest in equipment that offsets Putin’s A2/AD tactics: next-generation aircraft and anti-submarine defences that are less vulnerable to Russian firepower are needed.

Second, NATO should invest in the territorial defence of its eastern members. After years of training and equipping their militaries for missions outside Europe, states like Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Poland must now re-learn tactics for slowing a possible Russian advance and they need the alliance’s support to do this.

At the #NATO summit in Warsaw, NATO should invest in the territorial defence of its eastern members

NATO must also develop a clear message on deterrence and leave no doubt that NATO is a nuclear alliance. Three of its members possess nuclear capabilities, and NATO should be clear that nuclear blackmail from Russia, or anyone else, will never be tolerated. Moreover, NATO should stage more military exercises in regions that are vulnerable to a Russian A2/AD challenge, like the Baltic and Black Seas, and possibly the Arctic. Exercises should focus on increasing the readiness of all of NATO’s forces to move across Europe – not just its rapid response forces, as is the case now. Recent exercises, like ‘Allied Shield’ and ‘Trident Juncture’, which involved 15,000 and 36,000 personnel respectively, have been promising. But NATO should be able to train with larger numbers, particularly if Russia is doing so. This also requires taking a fresh look at equipment storage and transport across allied territory – not just along the borders. NATO should also agree on the conditions required for its strategic commander to deploy and exercise the rapid response force as he sees fit. At the moment he cannot respond quickly to developments and must wait for the result of a slow decision-making process. NATO should also help allies to respond to scenarios involving irregular forces, like the ‘little green men’ Russia used in Crimea, without giving Russia a pretext for military escalation.

Politically, NATO should work with vulnerable partners that are not members of the alliance. Russia’s manoeuvres in the Baltic Sea have alarmed Finland and Sweden – particularly the Russian exercise in March 2015 that simulated attacks on Finnish and Swedish islands. The Nordics should realise that, in the current environment, sitting on the fence may make them more vulnerable. NATO should promote close defence co-operation between the Baltic States, Poland, Finland and Sweden. The alliance should also continue to help build the capacities of the militaries of non-NATO countries in Eastern Europe, such as Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia.

Third, NATO needs to adopt tougher language towards Russia. The current Strategic Concept, dating from 2010, speaks of a NATO-Russian partnership. It is out of date. There should be no denial about the new challenge that Russia poses.

Finally, in times of increased tensions it is all the more important that NATO’s military staff continues to seek dialogue with military counterparts in Russia to avoid accidents and miscalculations. Whether Russia picks up the phone is a different question.

Rem Korteweg is a senior research fellow and Sophia Besch is the Clara Marina O'Donnell fellow at the Centre for European Reform.