Restricting immigration means constricting trade in services

The fortune of the UK’s all-important services sector after Brexit is inextricably linked to how open the country is to foreign workers and consumers.

Services account for around 45 per cent of total UK exports in value terms, an unusually high proportion for a medium-sized economy. The EU is the UK’s most important market, receiving roughly 40 per cent of UK services exports (the US is second, on 22 per cent). Services trade volumes are still lower than goods in most advanced economies because there is often the need for face-to-face contact.

Only 21 per cent of all EU services sold to the rest of the world are provided remotely – for example, by a London-based architect e-mailing plans to a client in New York, or a Parisian banker executing a trade following a phone call from a client based in Singapore. The rest are provided either via a foreign commercial presence (an Irish law firm operating out of an office established in Australia), by EU nationals travelling abroad to sell their services directly (a Swedish sustainability consultant jetting into Nigeria to complete an environmental impact assessment), or by foreign consumers entering the EU and purchasing services on location (Chinese tourists visiting Disneyland Paris). In practice, all of these modes of supply are reliant on people being able to easily move around the world.

Unless the UK prioritises increased openness to migrants, foreign workers and students, its attempts to open up new services markets at home and abroad will falter.

Unless the UK prioritises increased openness to migrants, foreign workers and students, its attempts to open up new services markets at home and abroad will falter. This is true of both services trade with the EU and the rest of the world. If the UK is to prioritise services trade with the EU, the free movement of people will need to be put back on the negotiating table; if the UK is to become a global services trading hub, it will need to create an immigration regime which prioritises enticing people in over keeping them out.

Trade with the EU

The EU will probably continue to refuse to split the four freedoms – the free movement of goods, capital, services and labour – which means that the UK’s decision to end the free movement of labour will prevent its services exporters from having full access to the EU’s single market. While the EU might go slightly further than it has done in previous trade agreements – particularly on mutual recognition of professional qualifications and the right to set up subsidiaries in EU member-states – once outside of the single market, the EU will treat Britain’s services much the same as it does with all other countries.

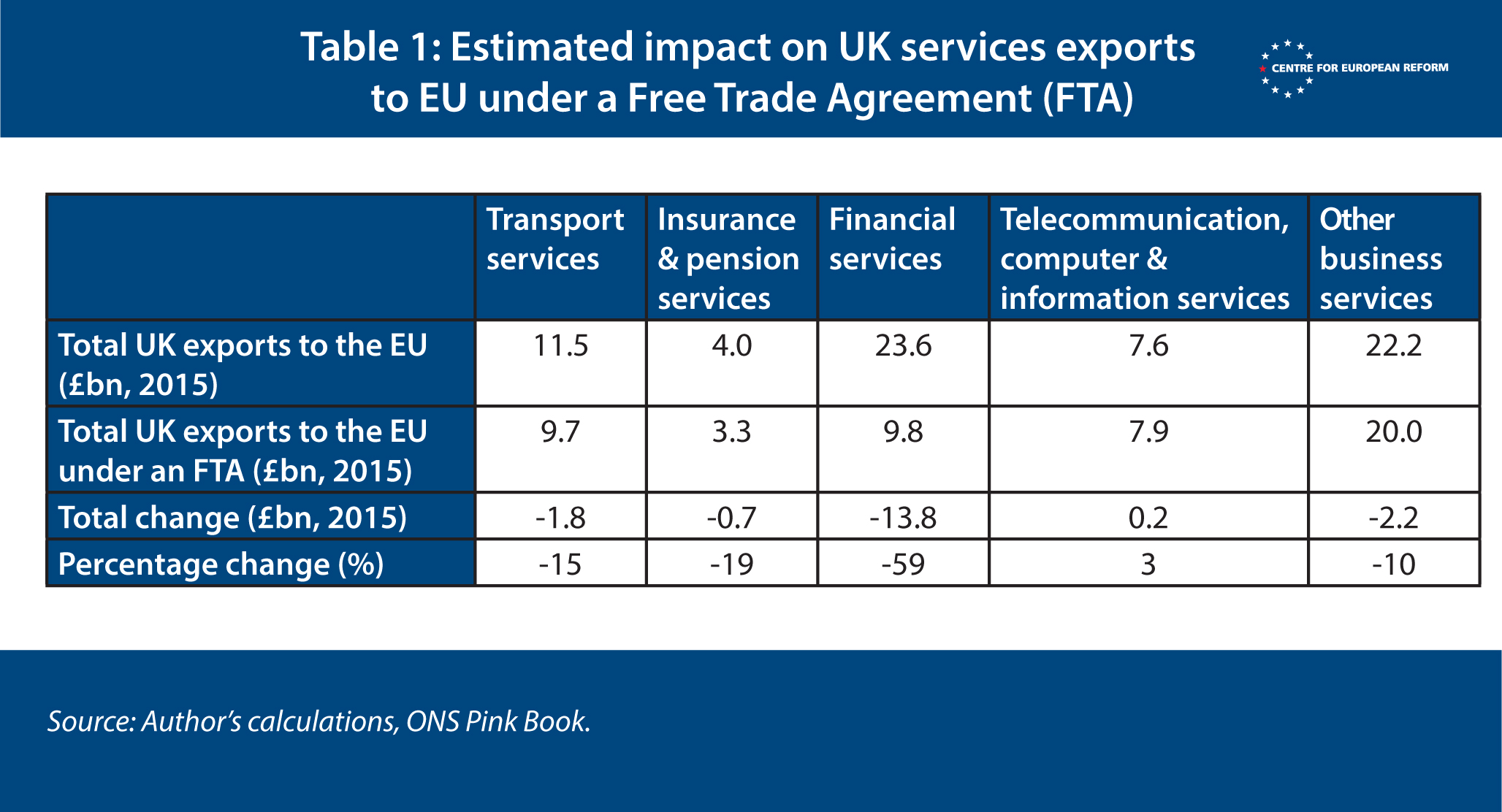

Not all sectors will suffer equally, but most will take a hit. Financial services are the most exposed, followed by insurance and pension services, transport services and business services (see Table 1).

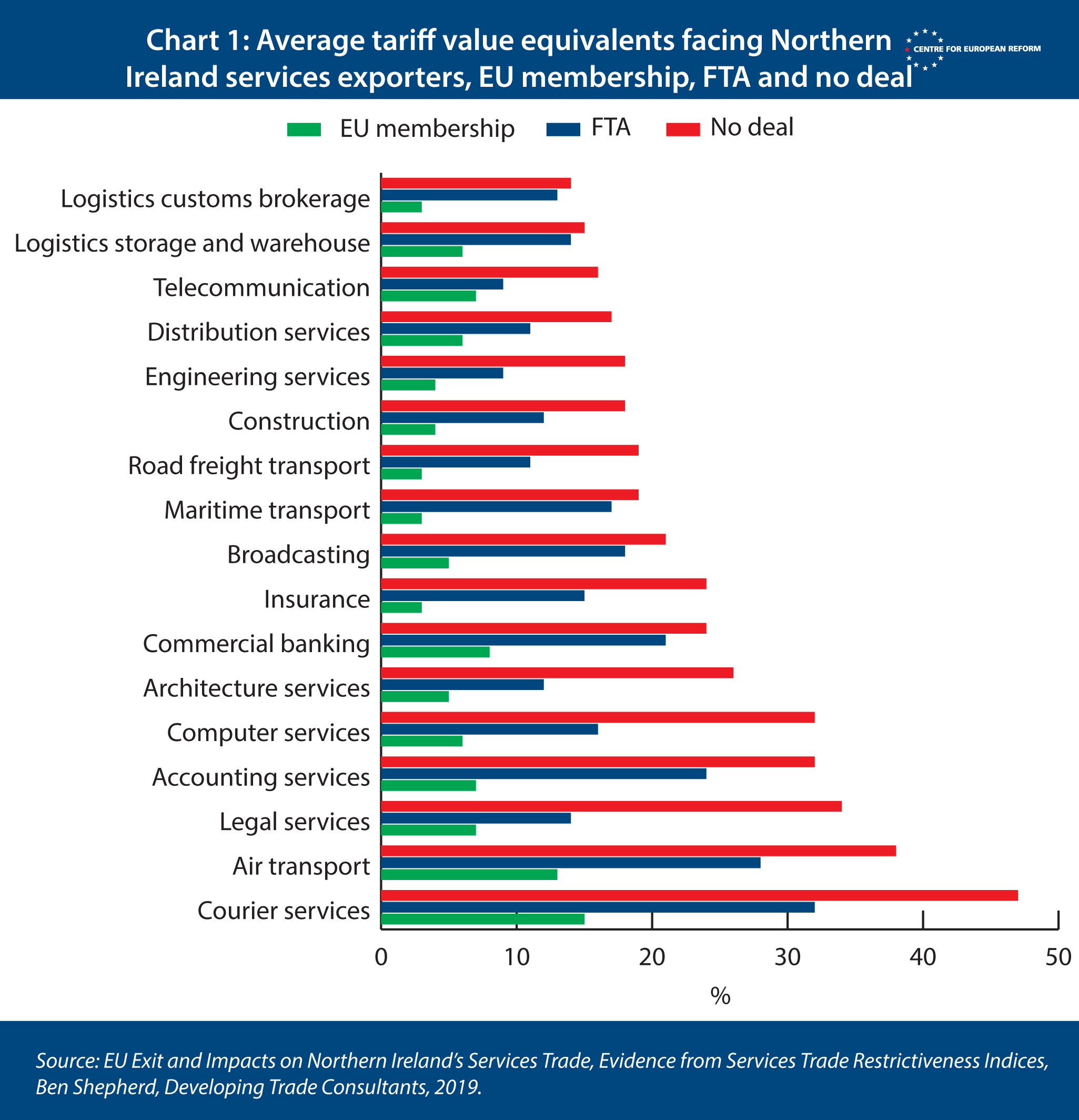

Research by the OECD and the Department for the Economy of Northern Ireland’s devolved government (DfE) support these findings. The OECD finds that restrictions on services trade between EU member-states are around four times lower than barriers to selling services into the single market from the outside. DfE’s research shows that, were the UK to enter into a free trade agreement with the EU, the sectors facing the biggest increase in barriers to trade include accounting services, commercial banking, insurance and broadcasting.

Britain’s position on EU migration will have direct implications for the UK’s services sector and its future access to the EU market. Compounding matters further, migration is economically beneficial in its own right: the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics estimates GDP would be 1.4 to 1.8 per cent lower as a result of ending freedom of movement and replacing it with a less liberal regime in the long run. While the UK’s Conservative government is hostile to freedom of movement, the economic rationale points firmly in the other direction.

Trade with the rest of the world

Opening up new services markets is difficult. Sections on services in trade agreements tend to do little more than re-assert previously made commitments at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and barely touch upon regulatory barriers to trade. There is only one example of progress in comprehensive, multi-country services liberalisation since the conclusion of the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services: the EU’s gradual development of the single market in services. However, some bilateral success has been achieved when it comes to making it easier for services firms to establish in foreign territories, and send over their workers for a fixed period of time.

Worldwide, services are largely provided via establishment – if a services provider wants to access a new country it usually sets up an office in it. There are many reasons for this: domestic regulators want to have jurisdiction and oversight of activity taking place in their territory, and tend not to favour mutual recognition; the necessity of face-to-face interaction; language constraints; and the value-added of local expertise. Establishment in another country is much easier if the provider is able to re-locate some of its home-country staff in its foreign enterprise, to get the business off the ground and instil the desired working culture. For trade policy to be effective, services and migration should go hand-in-hand – establishment is eased by sending over staff, while some things can be done remotely.

While the UK is broadly open to foreign companies establishing offices in its territory, it is not as generous when it comes to foreign workers. Thus the number one demand in future trade negotiations for countries such as India will be for the UK to grant increased numbers of business visas and make it easier for their citizens to temporarily work in the UK.

If the UK is to succeed in making it easier for its own world leading consultants, tech-engineers and specialists to work across the world, it will also need to open its own market to people from elsewhere.

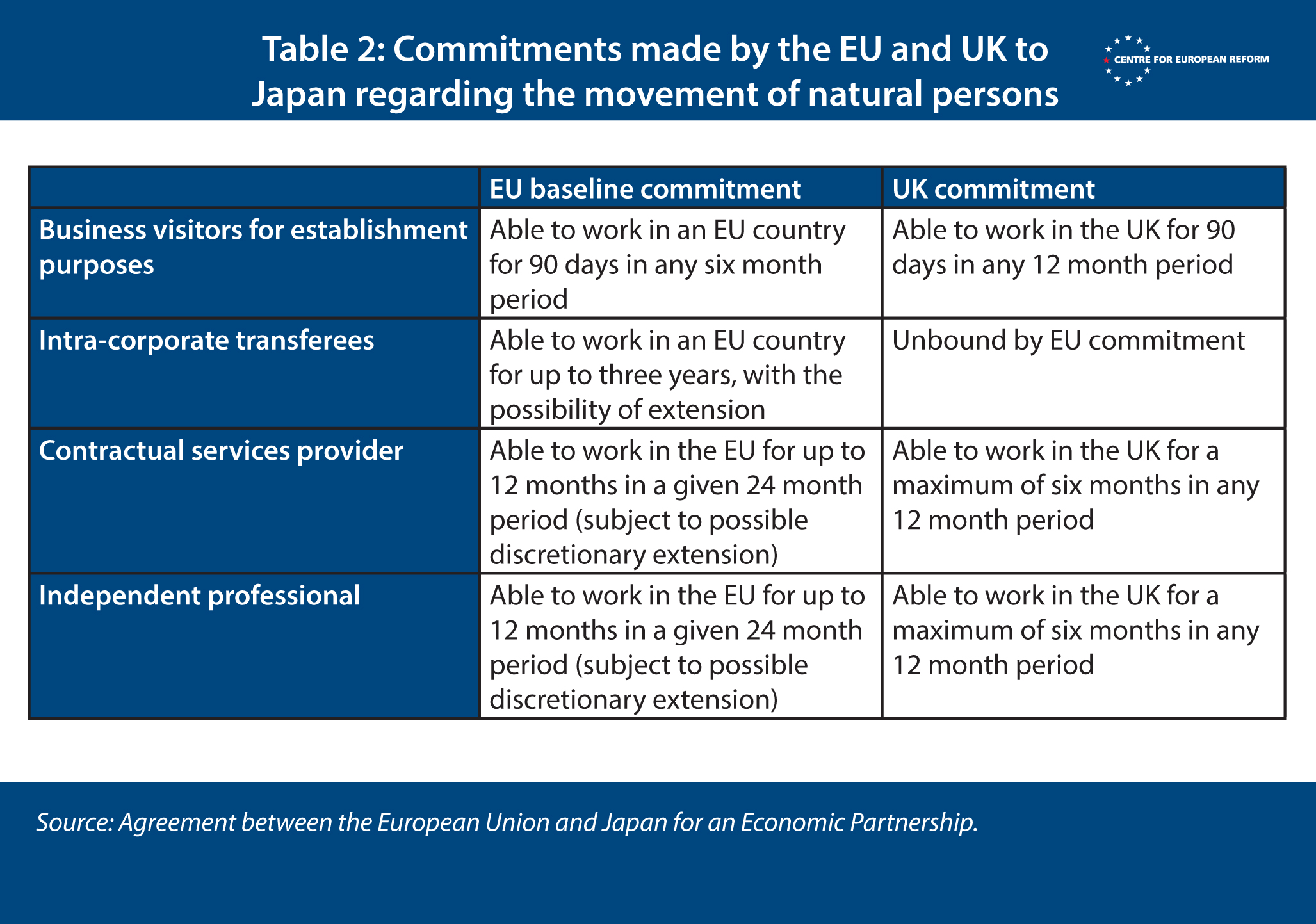

At present, the UK is among the more restrictive EU member-states when it comes to so-called ‘mode 4’ provisions found in trade agreements. These provisions are limited to specific services sectors and sub-sectors, and afford preferential treatment to short-term business visitors; intra-corporate transferees; and individual contractual services suppliers and independent professionals who enter a country to temporarily provide a service. For example, in its trade agreement with Japan, the UK has lodged reservations, offering less, on paper, than the default EU position (see Table 2).

The government white paper outlining plans for the UK’s new immigration system leaves open the possibility of granting preferential access to workers as part of future trade agreements. But the details are lacking. Mode 4 provisions also historically struggle from a lack of cross-government buy-in. Crudely speaking, the provisions negotiated by trade officials are often not wholly compatible with a country’s domestic migration regime. This means that when migration officials get round to implementing the agreed text they tend to do the bare minimum necessary to satisfy the commitments made in the trade talks.

To this regard, the UK has shown signs of preferring a more broad-based approach which moves beyond a narrow focus on the temporary movement of workers in specific services sectors. Post-Brexit, as a temporary measure, it has proposed pursuing agreements which allow workers from specified “low-risk” countries (presumed to mean citizens of countries allowed to use e-gates at British borders and the EU) to work in the UK for 12 months, followed by a 12 month “cooling off period”. This has been welcomed by business although questions remain as to whether the duration can be extended and if it could be expanded to a greater range of countries. The UK is also committed to abolishing the cap on high-skilled workers – something that will make it easier for foreign subsidiaries to bring in their own staff. Yet these positive policy moves are being undermined by the actions of the Home Office which seems determined to paint the UK in the worst light possible.

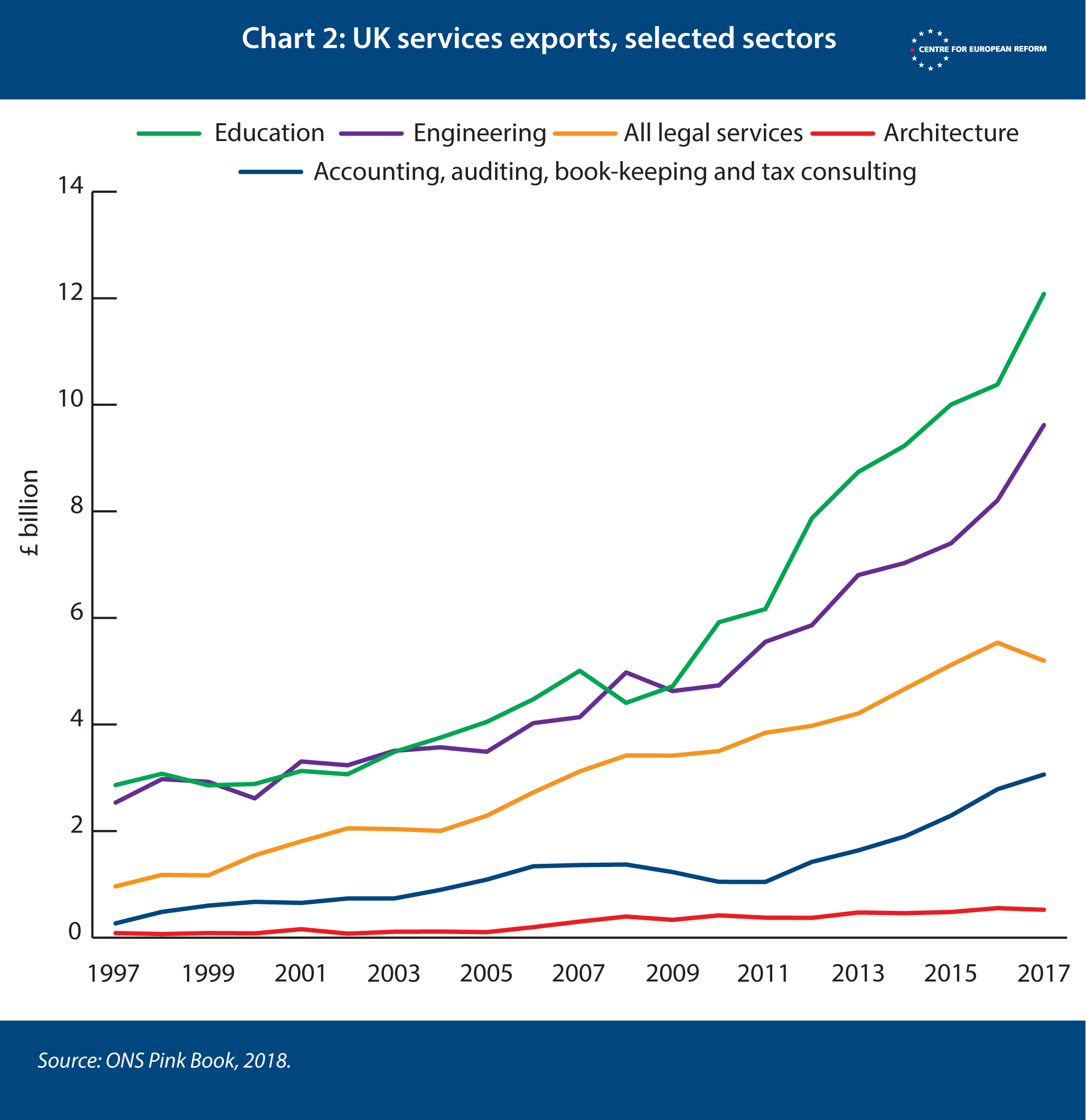

Hostility to immigration can also directly undermine services exports. The British education sector is one example. A foreign student attending a British fee-paying school or university is registered as a services export in the balance of payments statistics. (Just as when a foreign tourist visits the UK, the hotel they stay in is in fact exporting its services to the tourist.) Balance of payments data value education exports at just over £12 billion in 2016 (see Chart 2). The Department for Education estimates the value of education-related exports to be even higher, at £19.9 billion in 2016.

A sharp reduction in the time that foreign graduates are allowed to stay in the UK to find a job from two years to four months, combined with reported plans to charge EU nationals higher fees to attend British universities post-Brexit, run the risk of curtailing the sector’s success. While the weaker pound has made the UK relatively more affordable to foreign students in recent years, there are signs that the popularity of British institutions is faltering. Jo Johnson, the former minister for universities and science, noted in a recent blog post that the UK is already on track to miss its old target of £30 billion in education exports by 2020, and will inevitably miss the new target of £35 billion in education exports by 2030 unless there are significant shifts in immigration policy.

The success of the education sector relies heavily on increasing the number of international students moving to the UK. Yet, because foreign students are included in the UK’s net migration target, it is also in the Home Office’s interest to introduce policies designed to limit their numbers. This internal policy incoherence is clearly not going to achieve a satisfactory outcome, but, as noted by the Institute for Government, has unfortunately “been a constant through governments for years”.

The movement of people and movement of services are intertwined, and to embrace one is to embrace the other.

With much of the Brexit debate focusing on customs unions, border frictions and goods, the UK’s services industries have largely been ignored. This will not be the case forever. But if the UK is to embrace a global role as a vocal advocate of services liberalisation, it will need to rethink its approach to immigration. The movement of people and movement of services are intertwined, and to embrace one is to embrace the other. The British government will need to decide which to prioritise: arbitrary political targets for reducing the number of foreign people who move to the UK to study and work; or the future success of one of Britain’s few economic bright spots: traded services.

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment