Russia may ditch the dollar – but it needs the euro

Naysayers claim Western financial sanctions will speed Russia and China’s drift away from Western currencies and finance. But the West’s predominance in the global financial system is enduring.

Western nations have imposed severe sanctions on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine. The most immediately disruptive sanctions targeted the Russian financial system, impairing Russia’s ability to trade internationally and freezing around half of its nearly $600 billion foreign reserves.

Critics of these sanctions argue the West is self-sabotaging, for example by reneging on the institutional promise that Western central banks will always honour claims against them and by politicising Western financial systems. They argue Russia, and other countries wanting to insure themselves against Western sanctions, will simply use their own currencies and payment systems, making future sanctions less effective.

On cue, Putin has announced that Europe must now pay for Russian gas with roubles rather than euros. At the same time, Russia is pushing India to start paying for its gas in euros rather than dollars. This illustrates Russia’s dilemma: it cannot escape Western currencies. Western critics of financial sanctions miss a crucial point. To retain their international position, the West’s financial institutions and currencies do not need to be apolitical. They just need to be less politicised than the alternatives.

Russia’s trade depends on Western currencies

Start with how Western sanctions harm Russia’s trade. US financial sanctions excluded Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank, and the Russian central bank from clearing payments in US dollars, and froze the US assets of other important Russian banks. The US sanctions make it harder – though not necessarily impossible – for Russia to deal with US dollars. Any cross-border transaction in US dollars will, at some point, use a US intermediary bank and rely on US settlement systems, and therefore be susceptible to US sanctions.

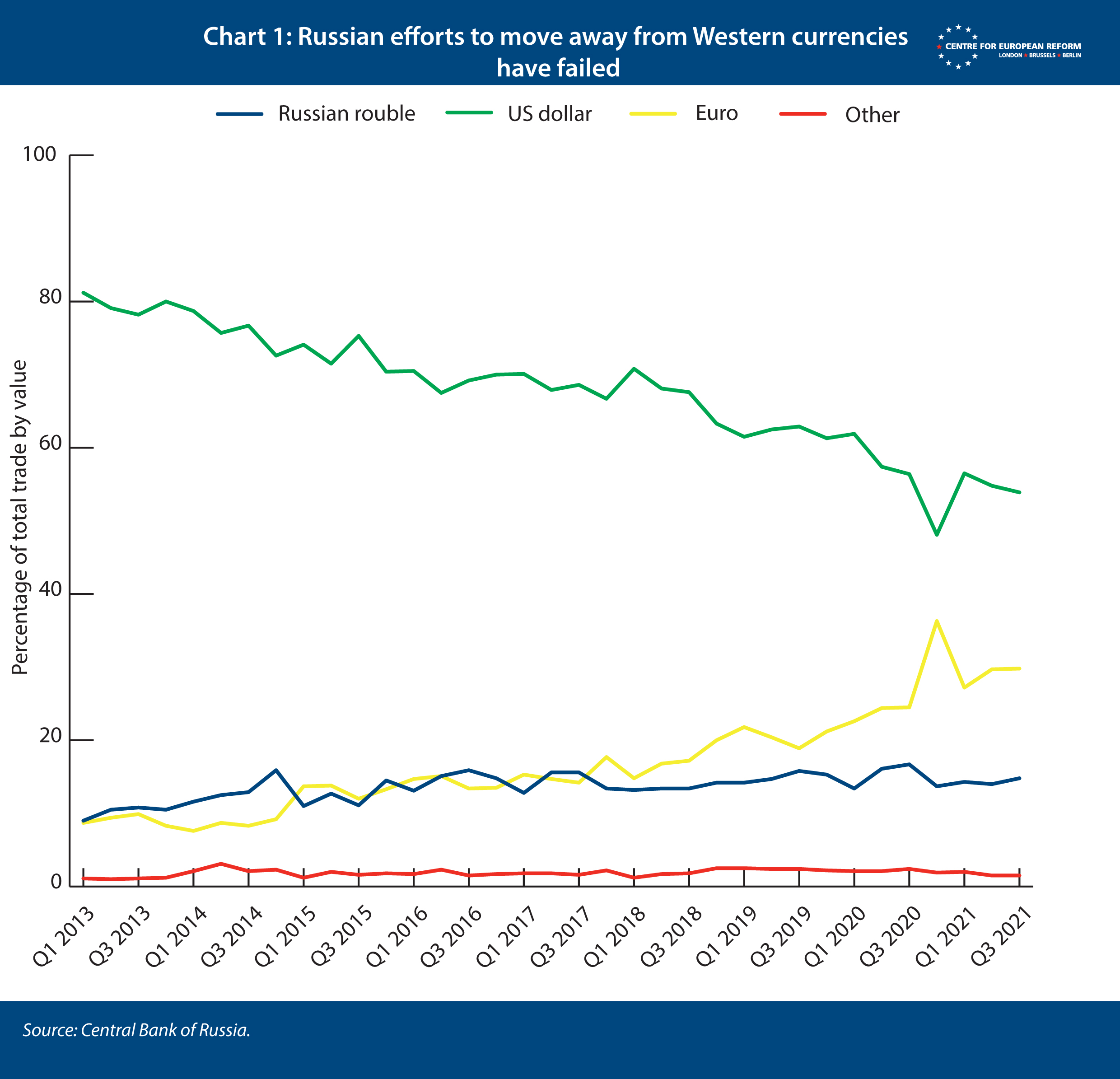

Russia has long been aware of the risks of using US dollars for its trade. It has successfully promoted the rouble’s use in transactions with other members of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) like Belarus. However, Russia has not, until now, insisted on using the rouble for trade outside the CIS. As Chart 1 shows, Russia’s global trade has been invoiced increasingly in euros in recent years instead, leaving the total share of Russia’s trade in Western currencies practically unchanged.

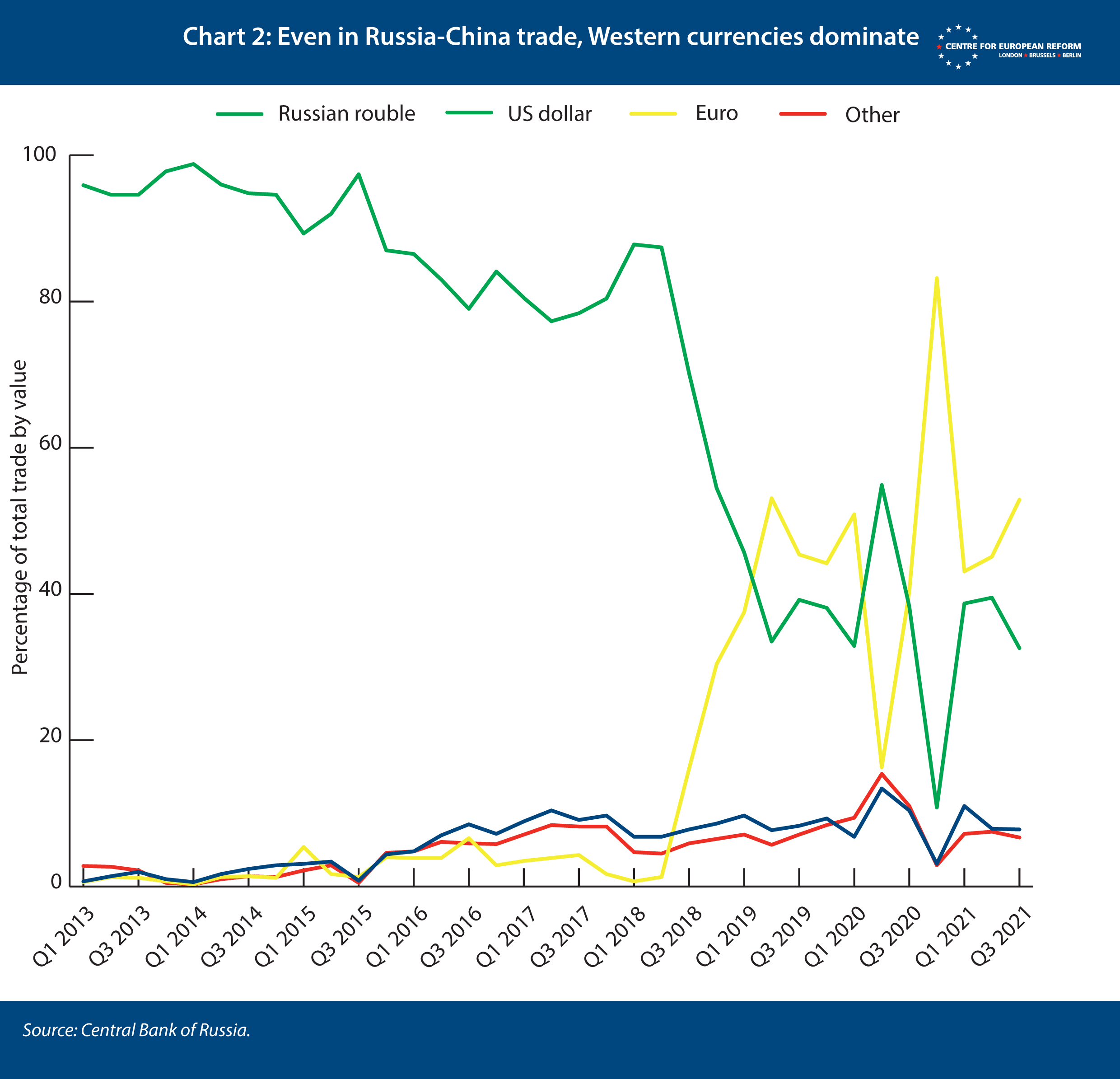

As Chart 2 shows, this trend is true even in Russia’s trade with China – despite China’s own ambitions to increase the international role of the renminbi and a 2019 agreement between Russia and China to settle their bilateral trade in renminbi or roubles.

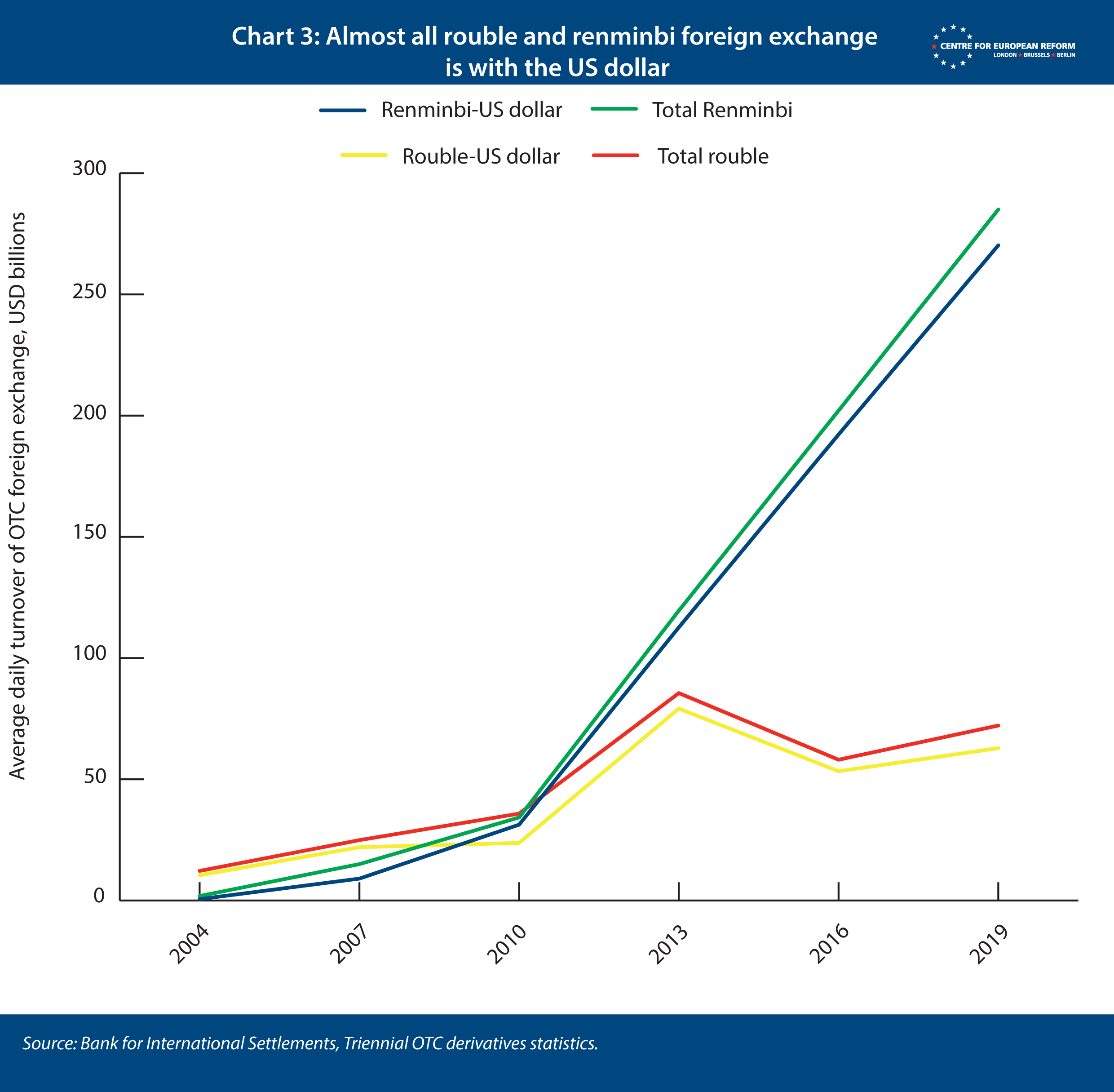

Russia pivoted to euros rather than renminbi or roubles because trading in renminbi or roubles would cost Russia more and reduce its choices. As Chart 3 shows, nearly all currency exchange involving roubles or renminbi are conversions to or from the US dollar. Even euros are much less liquid: 95 per cent of renminbi foreign exchange trades were to or from US dollar, whereas only just over 1 per cent were to or from the euro. Transactions between lesser-used currencies are rare and often performed ‘synthetically’, using the US dollar as an intermediary.

Russia pivoted to euros rather than renminbi or roubles because trading in renminbi or roubles would cost Russia more and reduce its choices.

As a result of Russia’s sanctions-induced crisis, China has tried to increase rouble–renminbi currency trading. Unlike most Western economies, China normally tightly manages exchange rates with its trade partners. But it has let the rouble plunge in value against the renminbi. This should have facilitated greater exchange volumes (though it will cause hardship for Russians, who will be less able to afford Chinese imports). Despite this, trading between renminbi and roubles is still pricey. The difference between bid and asking prices on rouble-renminbi trades recently widened to 0.0287: more than five times higher than the typical equivalent figures for converting US dollars to euros. This means there are still very few renminbi–rouble trades occurring, compared to dollar–rouble or euro–rouble trades, and the rouble’s real value cannot be easily assessed.

Against this background, Putin’s demand that Europe pay for gas with roubles seems to be grandstanding. European governments have so far refused Putin’s demand to pay for gas with roubles. Even if they agreed, this would only had Putin a symbolic victory. Unless Russia is trying to increase its revenues by using an artificial exchange rate, it would be better off with payments in euros, which it can force exporters to convert to roubles as necessary to maintain the value of the currency. This is why Russia has just asked India to pay for gas not by using roubles, renminbi or rupees – as has been constantly speculated in recent weeks – but in euros.

Russia and China’s alternatives are not credible

Russia and China have long recognised the problem that their currencies are not easily exchanged in high volumes. They have been trying to build cross-border payment infrastructure, including examining linked central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). These proposals face numerous hurdles in practice. For example, these arrangements are unproven without Western technology – China’s existing cross-border payment system, CIPS, processes few transactions and still relies on the Belgian-based SWIFT service, for example. And linked CBDCs require trust between central banks: each participating central bank would need to hold foreign collateral with other participating central banks. Central banks would also need complex agreements about how such programs would operate and who would provide liquidity in a crisis. These programs also involve significant macroeconomic risks, especially for economically weaker countries like Russia: at best, there are greater exchange rate risks; at worst, domestic users in Russia could start using the ‘digital renminbi’ over the rouble, undermining Russia’s monetary sovereignty.

Russia and China have long recognised their currencies are not easily exchanged. But proposals for cross-border payment infrastructure face numerous hurdles.

Russia’s attempts to become less dependent on Western currencies show just how difficult doing so is. The underlying reasons why the US dollar, and to a lesser extent the euro, remain predominant have not changed during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The US dollar and euro are by far the most widely used currencies globally, which creates network effects: the most useful currency is one others will most easily accept. There is a liquid market for safe dollar-denominated assets, for investors to store their dollars – while China and Russia have limited debt and their debt instruments are not traded in large volumes, so investors (or central banks) cannot be certain of being able to sell them in a crisis. US dollars are also more readily available: the US Federal Reserve has extended currency swaps to other central banks, to help these central banks manage their domestic financial markets and banking systems which use the dollar. The European Central Bank is following the Fed in making similar arrangements.

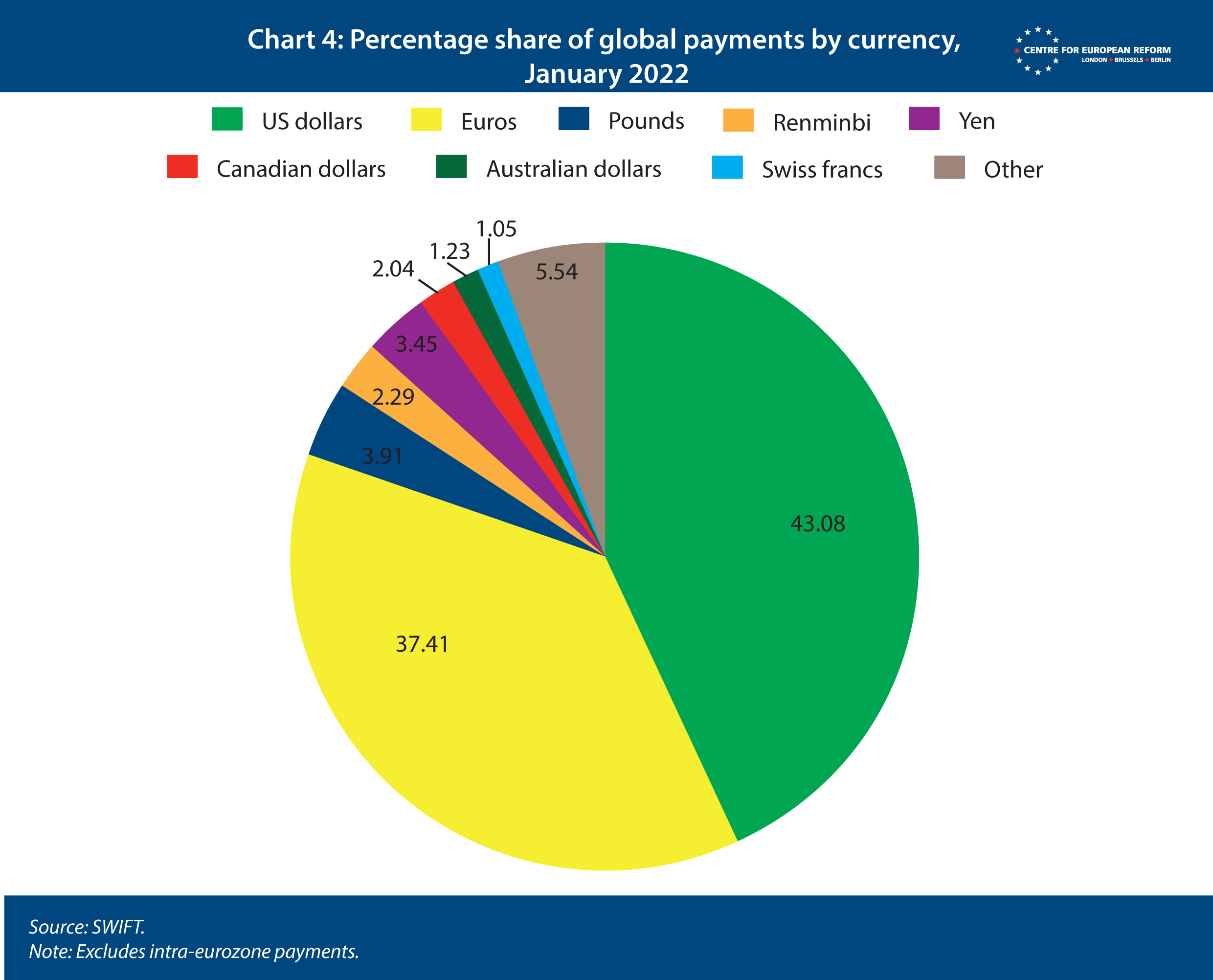

China has tried to mimic the US, extending currency swaps with many other central banks, including a RMB 150 billion currency swap with Russia in 2014. But the Russia-China arrangement – like the ECB’s – has barely been used. In part, this is because of the trade imbalance between the two countries; China’s fear of breaching sanctions laws; Russia’s fear of Chinese capital controls; and the instability of the rouble. But mostly, it is because there is simply far more demand for US-denominated debt, and because the Fed proved during the Covid-19 crisis it would buy back debt in whatever amounts were required to keep markets functioning. Finally, the size, stability and openness of Western economies, and Western governments’ commitment to the rule of law, ensures that government bonds and Western currencies are perceived as safer options than currencies whose exchange rates are not free-floating, which are subject to capital controls, and where investors have less trust in the stability of government policy. These factors explain why, as Chart 4 shows, the renminbi – while growing in importance – still accounts for only 2.29 per cent of global payments by value (excluding intra-eurozone payments), far less than China’s share of the global economy. The rouble’s share is negligible.

Western currencies remain the most useful foreign reserves

Aside from limiting Russia’s ability to trade, Western sanctions have also frozen the Russian central bank’s foreign reserves held in Western central banks. Central bank asset freezes are a near-ideal sanction since – unlike trade restrictions – they do little damage to Western countries. Furthermore, because asset freezes increase Russia’s immediate need for foreign currency, they make countermeasures – like cutting off Europe’s energy supplies – more painful for Russia. The asset freezes have caused significant damage to the Russian economy: the rouble plummeted, causing massive inflation and making imports more expensive, although Russia appears to have found strategies to stabilise its value using exporters’ foreign currency revenue in recent days.

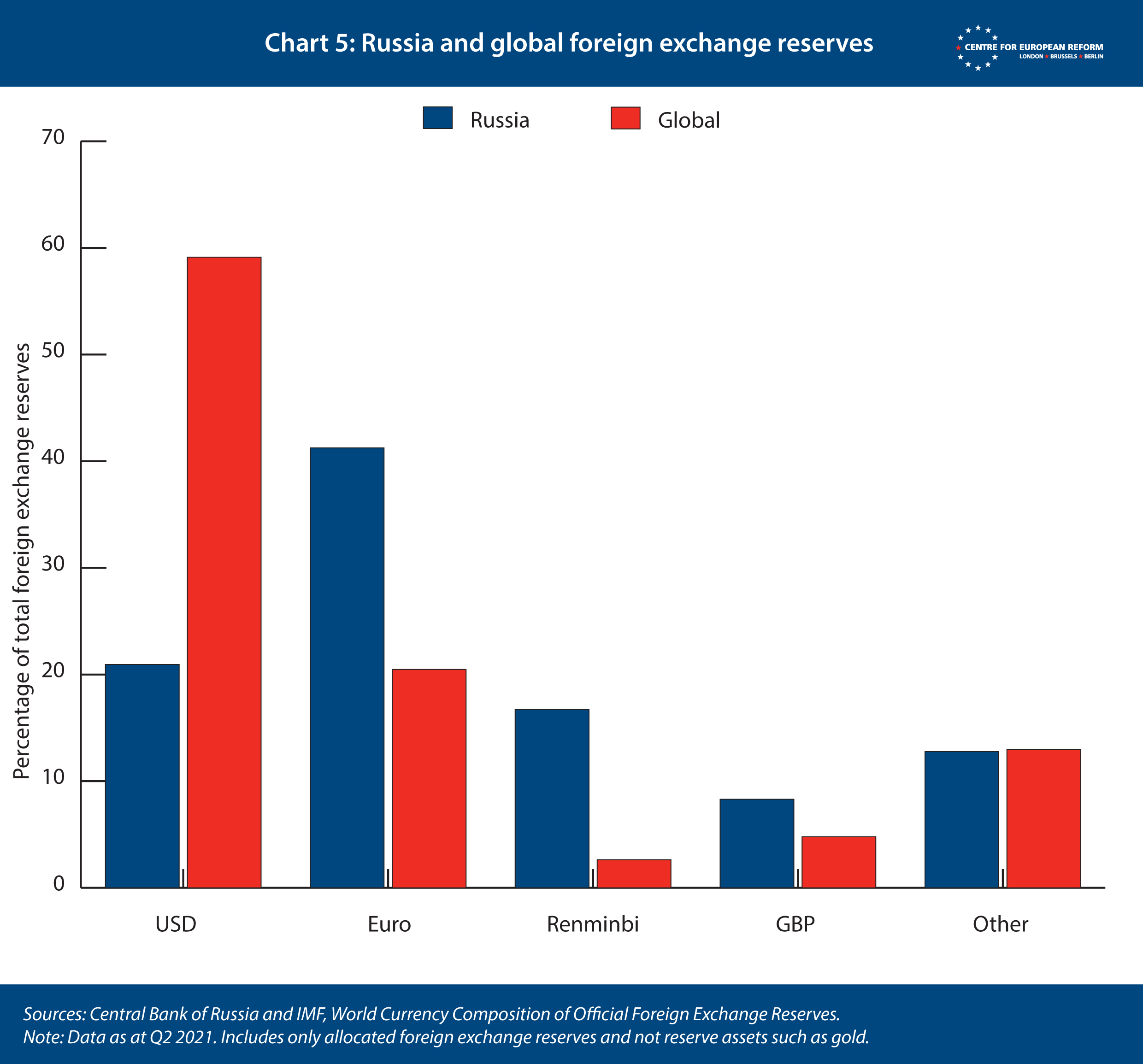

Russia anticipated America’s decision to freeze its central bank’s assets: in recent years it rapidly reduced the proportion of its foreign reserves held in US dollars to far below the global average. As Chart 5 shows, Russia now holds far less of its reserves in US dollars than most countries. Russia has been steadily increasing its reserves of euros, pounds and renminbi in recent years. Russia’s acquisition of euros was not necessarily a miscalculation. Instead, it simply shows that Russia and other countries that want to insulate themselves from Western sanctions have no better options than Western currencies for accruing a ‘war chest’. And this will remain the case, despite many claims to the contrary.

Russia and other countries that want to insulate themselves from Western sanctions have no better options than Western currencies for accruing a ‘war chest’.

First, banks and other firms in many non-Western countries remain reluctant to assist those subject to Western sanctions. Most sizeable economies are economically integrated with the West and will fear being cut off from Western markets. This is no clearer than in China, where the government is loudly condemning Western sanctions but many businesses are complying with them, because their business with the West is worth far more than their business with Russia.

Second, countries wanting to insulate themselves from Western sanctions could of course build up foreign reserves in each other’s currencies. But this is not especially attractive because non-Western currencies are far less liquid and demand for them is shallow, so they may end up being of limited use in a tight spot, when they are most needed.

Third, similar problems apply to Russia’s approximately $130 billion in gold reserves. Since the most active gold markets are in New York and London, sanctions can severely limit Russia’s ability to sell its gold reserves. Selling too much gold too quickly could also lower the market price, since there are far fewer buyers of gold than of US dollar assets. Russia will find selling gold in large quantities particularly difficult since much of its gold reserves are physically in Russia, rather than in larger gold markets where they could be targeted by asset freezes.

Finally, debate is raging about whether Russia could use cryptocurrencies like bitcoin to build or store wealth. Russia is one of the largest miners of bitcoin and the majority of funds earned from cryptocurrency heists ends up in the country. Suspicions that Russia might use cryptocurrencies to circumvent sanctions arose when, in January 2022, Putin canned a ban on cryptocurrencies proposed by the Russian central bank, and instead quickly published proposed regulations to grow the sector in Russia. As a result, the EU and the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control very quickly amended their sanctions regimes to explicitly include cryptocurrencies. Despite disagreements about how easily cryptocurrency usage can be tracked, the main hurdles to Russia using cryptocurrencies to support its economy are simple. Cryptocurrencies are highly volatile, making them a poor store of value; they are extremely expensive to transact with; and they have limited acceptance, so they need to be converted to fiat money to be useful.

Conclusion

Countries like Russia and China have few good options to cut out the West entirely – they may try to do so at the margins, but to cut out the West in any significant way would merely create worse vulnerabilities. For example, if they reduced their foreign reserves held in Western central banks, they would need to rely on assets with a less certain value and which could not be easily liquidated when they are most needed.

The Russian central bank has been able to mitigate the impact of sanctions to some degree. This is mostly because existing sanctions – deliberately or otherwise – continue to allow Russia to use euros and US dollars. It is not because Russia has found ways to cut out Western financial systems.

The West’s sanctions do little to undermine Western predominance in the global financial system. The opposite is true. Russia is desperate to insist that it is, unlike the West, a reliable business partner. But the more Russia politicises its financial systems – for example, by Russia forcing its exporters to sell most of their foreign currency to the central bank, or unilaterally deciding Europeans must pay for gas in roubles – the greater the protection offered by Western currencies will be.

Zach Meyers is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment