What a Boris Johnson EU-UK free trade agreement means for business

Johnson's EU-UK free trade agreement would increase friction and costs of trading with the EU. Many businesses would find adapting to a new FTA just as troublesome as if the UK had crashed out without a deal.

Boris Johnson intends to lead the UK out of the EU on January 31st 2020, and to use the subsequent transition period to negotiate a free trade agreement (FTA) with the EU. Yet not enough attention has been given to the practical consequences of his proposal, and the pain it will cause for significant sectors of the British economy. In practice, while an FTA with the EU could lead to the conditional removal of tariffs and quotas, it would still create a lot more trade friction and cost than currently exists. A December 2020 shift to an FTA with the EU would require many British businesses to adjust as much as if the UK were to exit without any future relationship in place. Under the withdrawal agreement Northern Ireland will have supplementary provisions leaving it far more integrated with the EU’s single market and customs union than the rest of the country, so this piece focuses on the EU’s trading relationship with Great Britain.

Johnson has prioritised domestic regulatory flexibility, and the freedom to negotiate new FTAs with countries such as the US, Australia and New Zealand, over economic integration with the EU. This choice rules out closer EU-UK models of integration, such as a partnership built on a customs union, or regulatory integration akin to the EU’s relationship with Switzerland or (even closer) the EEA/EFTA countries. What is left is an FTA. And no matter how ambitious an EU-UK FTA is, there are known limits to how much it can do to liberalise trade.

Trade in goods and agrifood

At its most expansive, an FTA between the EU and UK could remove tariffs and quotas on all goods traded between the two territories. However, fully tariff and quota-free trade will be dependent on the UK complying with EU level playing field demands on state aid, the environment and labour rights that go beyond what the EU would normally ask of an FTA partner. The EU's justification for asking more of the UK than others is that it is a large economy that is very nearby. If the UK refuses to concede to the EU’s demands, the EU will probably refuse to remove tariffs in certain sectors such as fish and agriculture.

Yet even assuming that the FTA does fully remove tariffs and quotas, zero-tariff trade would not automatically apply. In order to qualify for it, exporters would need to prove that their products met the rules of origin criteria of the EU-UK FTA, that is to say that goods entering the EU from the UK were really produced in the UK (and not in China, say). Compliance with these rules comes with complications, paperwork and cost. As a result, few FTAs come close to being fully utilised by exporters, which either fail to qualify for zero-tariff trade, or decide the hassle of qualifying is not worth it.

Additionally, UK value-added will no longer count towards meeting the local-content requirements of existing EU FTAs with countries such as South Africa, Japan, Canada, South Korea and Mexico. For example, for a car to qualify for zero tariffs under the EU’s FTA with South Korea, 55 per cent of its value must have been created in the EU. Post-Brexit, UK-sourced components will no longer be considered as EU-originating and will therefore no longer count towards meeting the 55 per cent threshold. Companies exporting from the EU under the terms of these agreements will need to assess the viability of continuing to source inputs from the UK.

On the customs and administrative side, the political declaration envisages close co-operation between the UK and EU. But the stated ambition is to reduce friction and cost, not to remove it entirely. This means businesses trading between the EU and UK will need to deal with import and export formalities, including customs and security declarations, risk-based inspections, and the payment of tariffs (when goods are not covered by the FTA) and other taxes payable upon import such as VAT and excise duty.

British exports of products of animal origin will need to be accompanied by export health certificates signed by a vet, and enter the EU via a veterinary border inspection post where 100 per cent of shipments will be subject to document and identity checks, and up to 50 per cent subject to further physical inspections. The rate of physical inspection can be reduced, as it has been in previous EU agreements with countries such as New Zealand and Canada, but unless the UK is to integrate itself within the EU’s sanitary and phytosanitary regime (for food and plant hygiene) there is little chance of removing the need for controls entirely.

An FTA is unlikely to allow UK regulators to continue to sign off highly regulated products looking to be placed on the EU market. This will require British producers of new automobiles, pharmaceuticals, medical devices and dangerous chemicals to seek regulatory approval within the EU, as well as the UK.

While British manufacturers will continue to be able to self-certify that low-risk products meet EU standards, their EU-based importer will now be held responsible for placing the products on the EU market (unlike now, where the responsibility lies solely with the British producer). This has implications for legal liability and product-labelling and is a responsibility that some EU buyers are unwilling to take on. However, not all products can be self-certified by the producer. This is one area where an EU-UK FTA could prove far superior to trading under their respective World Trade Organization commitments. As in numerous other EU trade agreements, certifications produced by UK-based notified bodies – organisations responsible for verifying that riskier products have indeed been produced to a given standard – could continue to be recognised by EU authorities, in certain sectors.

Ultimately, an FTA creates a situation whereby trade in final industrial products will be slightly more constrained than now, but they could still be sold competitively in both the UK and EU markets. However the additional friction will make it difficult for the UK to remain intertwined in pan-EU manufacturing supply chains. This will encourage some companies to produce solely in the EU-27, and export the final product to the UK (and potentially vice-versa in specific circumstances). If, following the general election, Johnson’s FTA looks like it will become the final landing zone, the transition period would buy a little more time for companies to restructure their European operations accordingly.

Services and data

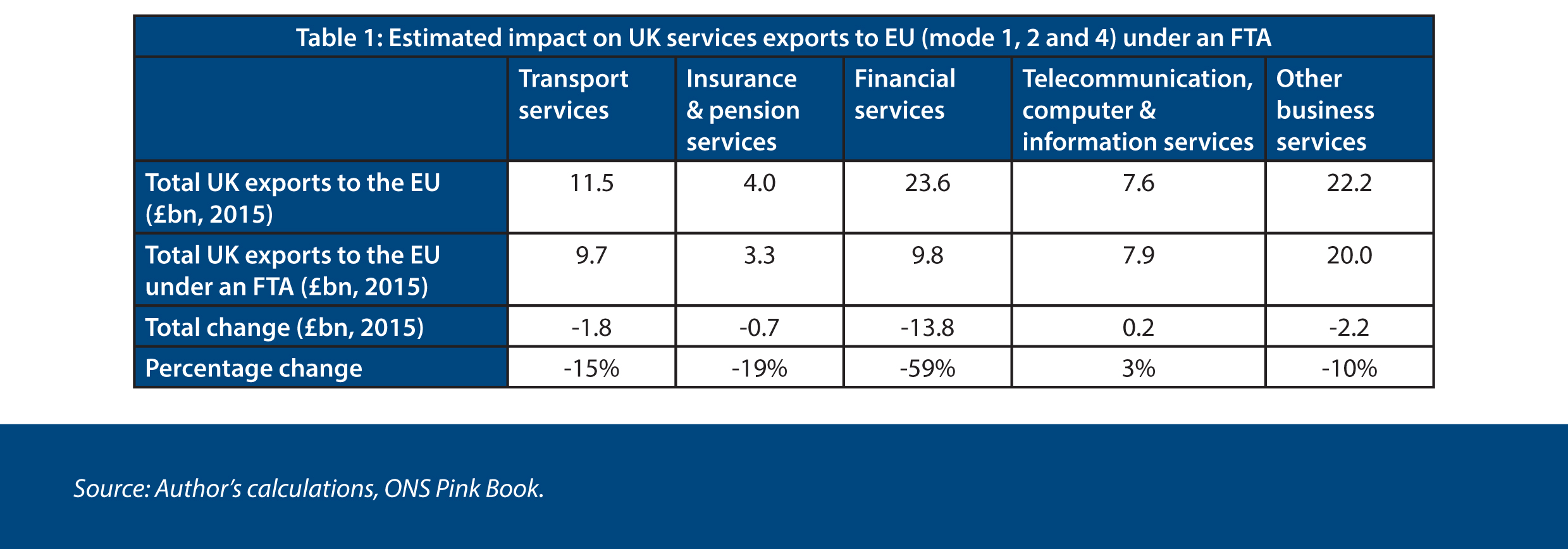

If the UK exits the single market as planned, the opportunities for continued cross-border services trade liberalisation are limited. While the EU will probably continue to make it easy for British services providers to incorporate and set up subsidiaries within the EU, it will become much more difficult to export directly from the UK. The logical consequence of this will be a medium-term shift in investment out of the UK and into the EU-27, as businesses restructure so as to continue servicing their EU-based clients. However, the magnitude of this shift will vary sector-by-sector, and is largely dependent on the type of services and the means by which they are currently supplied (Table 1).

The financial services sector, which will lose the ability to trade freely across all EU member-states (the so-called financial passport), would be the most exposed to new barriers to trade. The impact could be softened, however, if the EU recognised the UK as ‘equivalent’ for regulatory purposes, and if EU regulators took unilateral measures to allow activity to continue in the UK for a period of time, such as allowing EU derivatives contracts to be cleared in London. That would help to avoid triggering potentially systemic shocks. The political declaration commits the EU to finalising its equivalence assessments by the end of 2020. The EU is known for politicising the assessment process, and has explicitly used it as leverage in broader negotiations. In the case of Switzerland, the EU let the equivalence regime allowing EU investment firms to trade on the Swiss stock exchange in the hope of forcing the country to sign a new, unrelated, institutional framework agreement. Nonetheless, technically speaking, the UK should have little problem in meeting the EU’s criteria, at least as long as it avoids the temptation to diverge substantially from EU approaches. As with other EU FTAs, an agreement with the UK would probably include a chapter on financial services, focusing on regulatory dialogue and interaction between EU and UK regulators.

As in the case of the EU–Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, an EU-UK FTA will probably be accompanied by a data adequacy ruling. This would allow businesses to continue to store the personal data of EU citizens within the UK, and is a clear improvement over having no arrangements in place.

There is potential for the EU to move further than it has done in the past on issues such as the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, but doing so will prove tricky. The recognition of non-EU/EEA qualifications is largely done by individual member-states, and it is not in the EU’s gift to offer blanket recognition to a third country. In practice, much as it has done in FTAs with Canada and Japan, the EU will probably agree to facilitate a dialogue between member-state certification bodies and their equivalents in the UK, but little more. This is far inferior to what exists now, whereby UK qualifications are broadly recognised across the EU (with some caveats).

The parameters of Johnson’s proposed EU-UK FTA are predictable, along with the potential impact on trade. However, the political and public debate has still not got to grips with the trade-offs involved. In all likelihood, once the realities of trading under an FTA become apparent, the political pressure to seek a more substantial agreement will grow. Even if EU-UK FTA negotiations are concluded before the end of December 2020, which is a tall order, either an extension of the transition period or a new phased implementation period would be necessary to allow businesses to adapt to the new reality and avoid a day one economic rupture similar in scale to crashing out of the EU with no deal. Leaving the EU does not bring the Brexit debate to a close; it just moves it on to the next phase.

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Anyway , despite asking this question many many times, I cannot ascertain if 'passporting' of this type of financial transaction would be adversely affected, in any circumstances, following BREXIT. Although DWP announcements state that pension will be paid, CONVENIENTLY, DWP does not say that 'passporting' of this type of transaction will continue - and a positive statement needs to be made - in a situation of no trust in anything this slippery government says. eg. on 1 September Amber Rudd said pension increases in EU countries would be uprated until 2023, but in October, the new DWP Czar, Theresa Coffey, said ' only for the lifetime of this parliament. - which , of course has now ended. Given that one needs to start trusting something - what response would you like to make to this enquiry ?

Add new comment