Will courting Putin always end in tears?

Putin is good at persuading Western leaders that bad relations with Russia are their fault. They should defend their interests better, but also keep talking to Russia.

For most of the last 20 years, various Western leaders have tried and failed to establish mutually beneficial relations with Russia. Relations were worse when Tony Blair left office in 2007 than when he was the first Western leader to visit then acting President Vladimir Putin in St Petersburg in March 2000. And they are even worse now, as Angela Merkel comes to the end of her time as Chancellor, than when she took power in 2005. European and American leaders have come and gone; the constant factor has been Putin.

Putin is a master of gaslighting. He has persuaded many of his Western colleagues that bad relations are the fault of their predecessors (or of other Western leaders): they enlarged NATO and the EU, interfered in Russia’s neighbourhood (broadly defined), and did not respect Russia’s views on issues such as Western intervention in Libya. He ignores the tensions caused by Russia’s murder of Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006, its invasions of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, and its repeated violations of international arms control treaties.

Putin is a master of gaslighting. He has persuaded many of his Western colleagues that bad relations are the fault of their predecessors (or of other Western leaders) and ignores the tensions caused by Russia’s own actions.

The West is at risk of being taken in by Putin again. This year’s Munich Security Conference (MSC) saw French President Emmanuel Macron arguing that no-one in the West is prepared to be “brutal” and make Russia respect boundaries, so renewed strategic dialogue is the best alternative. And a group of former senior politicians, officials, think-tankers and military officers from Europe, Russia and the US published a 12-point plan for peace in Ukraine on the MSC website, without mentioning that there would have been no conflict there if Russia had not annexed Crimea and invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014.

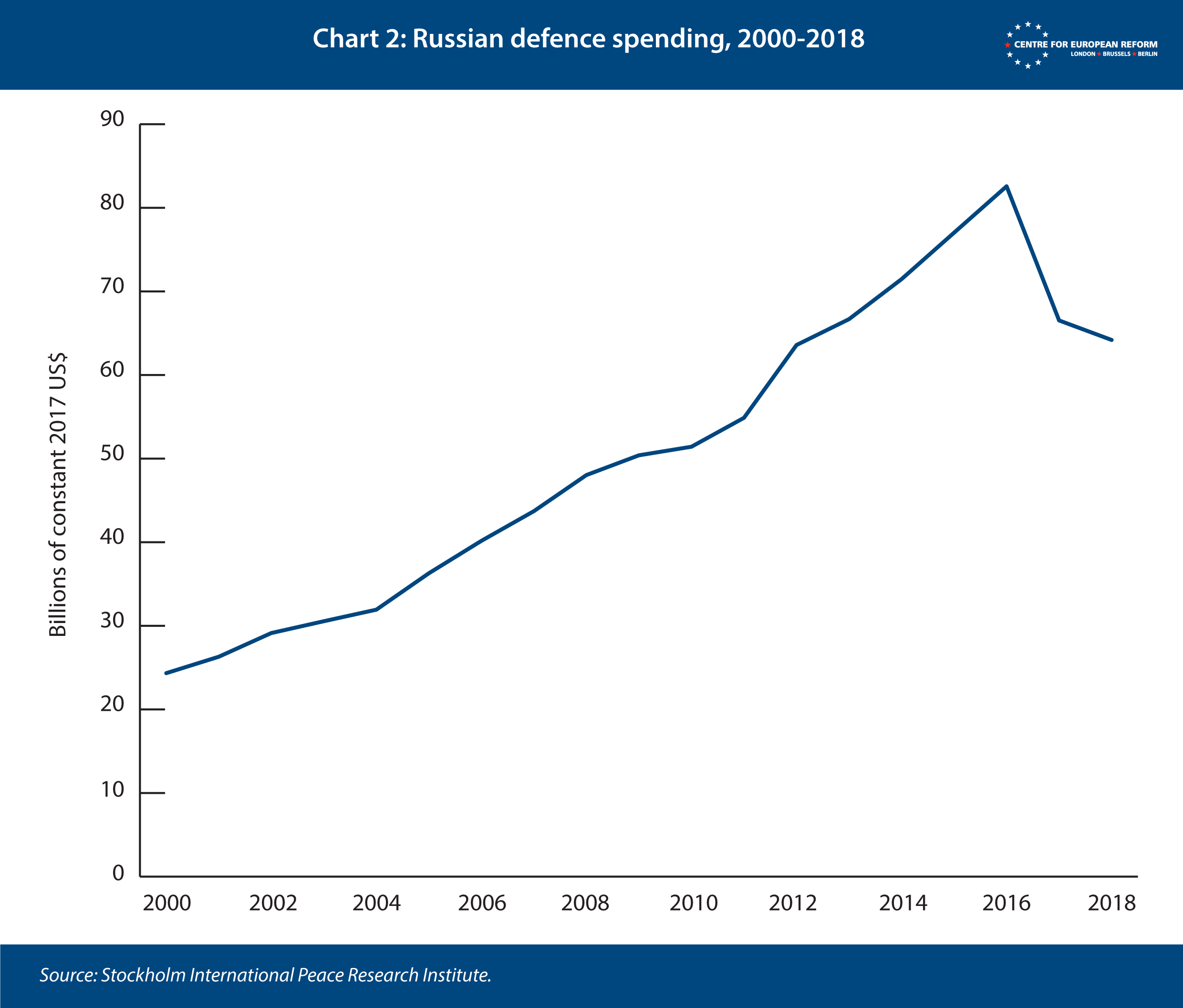

Putin and his allies see Russia as a ‘besieged fortress’ (to use Lenin’s term), surrounded by enemies, and have responded with a twin-track approach. One track is strengthening Russia. In every year but one from 2000-2010, Russian GDP grew by more than 4 per cent; that enabled Putin to launch a major programme of military renewal, following a decade of neglect after the break-up of the Soviet Union. He has justified the increase in Russia’s military power as a response to NATO’s expansion.

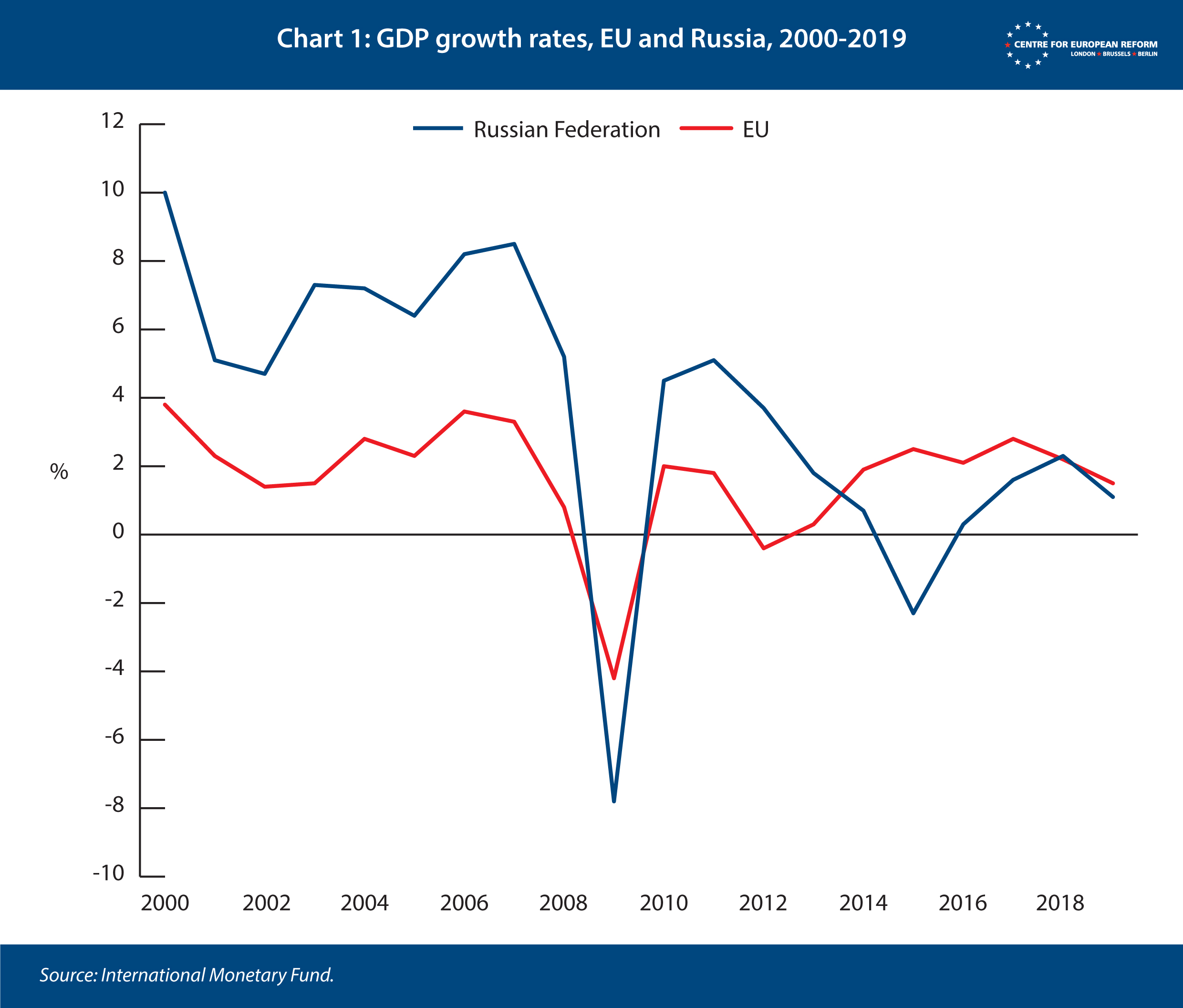

Since the global financial crisis in 2008-2009, however, Russia’s economic performance has deteriorated: GDP growth has been lower than the EU’s in five of the last six years (Chart 1). Russia’s defence budget, which increased every year from 2000 to 2016, is now falling (Chart 2). Meanwhile, NATO defence spending, which fell every year from 2010 to 2015, has begun to increase slightly, largely in reaction to Russia’s intervention in Ukraine.

As economic problems have restricted his ability to strengthen Russia further, Putin’s second track has been to weaken his adversaries. He has had some success in exploiting tensions between and within Western states to undermine EU and NATO unity and the internal coherence of individual states. Putin did not create euroscepticism in the UK, but Russian propaganda channels like RT were always happy to give a platform to pro-Brexit British politicians. While Russia itself ruthlessly suppresses separatism in the North Caucasus, state-controlled Sputnik radio’s Edinburgh studio regularly broadcasts material on Scotland with a pro-independence slant. Russia’s intelligence services did what they could to facilitate Donald Trump’s election as US president in 2016 (and seem to be doing the same for the 2020 election). Within Europe, despite loudly (and falsely) complaining that countries like Ukraine and Latvia are under the influence of neo-Nazis, Russia supports a variety of extreme right-wing organisations, both overtly and covertly.

It is a logical tactic for Putin to seek to divide and weaken those he perceives as Russia’s adversaries. If Western leaders, including Macron, are to avoid helping him, they should follow six principles.

First, know the facts, and challenge Putin and Russian officials and media when they distort them. Putin himself has just said in an interview about Ukraine: “For us to talk about today and tomorrow, we need to know history”. But Western leaders and opinion-formers should not base their policy prescriptions upon Putin’s version of the past. This year, with the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II in May, the Russian authorities have been keen to take credit for the victory (when other former Soviet Republics, notably Belarus and Ukraine, suffered proportionately larger casualties than Russia, and the Soviet Union would have struggled to win without UK and US assistance). But they claim that others are ‘re-writing history’ when they recall the atrocities committed by the Soviet Union in Central and Eastern Europe, both before 1941 and once the Nazis were defeated. Western leaders who celebrate Victory Day in Moscow on May 9th, as Macron and Trump plan to, should not endorse Putin’s mythology. In his interview on Ukraine, Putin suggests that the Ukrainian language exists only because of ‘polonisation’ of the population on Russia’s western border in the Middle Ages, and that Ukrainians and Russians are one people, with the same language, history and culture. The historical narrative is dubious, and Putin’s conclusion is plainly false in the 21st century, when Ukraine is a sovereign state with an increasingly strong national identity; Western leaders should not be afraid to say so. They should also be willing to correct publicly his claims about the nature of events in Ukraine: the war there is not a civil conflict between separatists in the east and a regime in Kyiv set up as a result of a Western-inspired coup, but an interstate conflict between a democratically-elected Ukrainian government and Russia, which would never have started and would not continue without Russia’s unavowed military intervention.

Despite Macron’s doubts, sanctions are a useful tool – Putin would not work so hard to undermine them otherwise.

Second, be ready to respond to Russia’s behaviour when it violates international norms. In the last six years, Russia has annexed Crimea; bombed hospitals in Syria (extensively documented by the open source intelligence website Bellingcat and by The New York Times); assassinated Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Germany and Imran Aliev in France; attempted to murder Sergei Skripal in the UK; and attacked other enemies on foreign soil. The co-ordinated Western reaction to the bungled assassination attempt on Skripal, including the mass expulsion of Russian spies from Western countries and public exposure of those involved, should be a model. Despite Macron’s doubts, sanctions are a useful tool – Putin would not work so hard to undermine them otherwise. There need to be clear conditions for lifting them, however, and the EU needs to find a way to avoid the regular ritual of countries like Italy threatening to veto their renewal – for example, by making sanctions decisions subject to qualified majority voting rather than unanimity. It is tempting to hold back criticism for fear of making relations worse, or to persuade oneself that the West is just as bad. Donald Trump, after an interviewer told him in 2017 “Putin’s a killer”, responded “We’ve got a lot of killers. What, do you think our country’s so innocent?”. But public Western criticism of Soviet behaviour did not prevent the two sides defusing tensions from the 1970s onwards, and opponents of communist regimes were encouraged by the knowledge that the outside world was watching.

Third, never lose sight of Western interests. Putin skilfully gets Western leaders to see his interests as more legitimate than their own. His interlocutors must remind themselves that a democratic, prosperous and well-governed Ukraine is a better neighbour than an impoverished and corrupt client state of Russia; they should not accept his perspective that Russia’s view on the future direction of Ukraine should carry more weight than that of Ukraine’s Western neighbours or even of the Ukrainian people. Putin is also good at manipulating his colleagues into taking policy options that they wrongly think will benefit them. In recent years, he has used dramatic announcements about hypersonic warheads, nuclear-powered cruise missiles and the like to persuade Western politicians that they are being drawn into an arms race that the West cannot win, and that they should therefore engage in discussions of European security architecture on Russian terms. In reality Putin is bluffing: the Russian economy could not sustain full-scale production and deployment of such systems.

Fourth, remain united. The Soviet Union worked hard but unsuccessfully to divide the West during the Cold War; Putin has done better, thanks in large part to mistakes by his Western counterparts. Putin has persuaded Germany to ignore the protests of its neighbours and get Russian gas via the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, making Ukraine – through which the gas currently transits – more vulnerable to Russian energy blackmail. He has seduced some Western leaders, like Trump, or Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, with his strongman image and promotion of ‘traditional values’. With others, such as Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, he has played on their distrust of their other allies. Trump’s regular rhetorical attacks on the EU and NATO have a corrosive effect on Western cohesion; but it does not help when Macron implies that Europe is not a partner of the US but merely “the theatre of a strategic battle between the United States and Russia”. The interests and values of liberal democracies are largely convergent with each other, but mostly at odds with those of the Russian leadership; Western leaders should focus on that fact. It is good that Macron is sending his Russia envoy, former Secretary General of the European External Action Service Pierre Vimont* to talk to EU member-states about his initiative. It would have been better, however, if he had tried to find a measure of agreement about aims and methods before launching his proposals publicly.

Fifth, do not isolate Russia completely. There are plenty of reasons to distrust Putin, to be appalled by things that his regime has done or to reject his world view. It is easy to respond by not talking to the Russian authorities – an apparently cost-free sanction. It is a mistake, however. Talking does not mean agreeing, or making concessions; but it is a chance to ensure that the sides understand each other and know where their red lines are. There is much more risk of unintended escalation when direct contacts between the leaders of Russia and the West and between their military staffs are frozen. Whatever the frustrations and inadequacies of the ‘Normandy format’ meetings between France, Germany, Russia and Ukraine, Macron was right in his Munich interview to say that they should be more frequent. Russia and the West also need to talk about nuclear and conventional arms control, military confidence-building measures, global non-proliferation issues and regional conflicts such as that in Libya – even if they do not reach any rapid agreement.

The West should challenge hostile stereotypes propagated in Russian state media by showing its willingness to work with Russia wherever that is possible.

Sixth, seek out areas of potential co-operation that are not as politically sensitive as frozen conflicts in Eastern Europe or arms control. Climate change and the shift to a low carbon economy are issues that will affect the EU and Russia, albeit in very different ways. Russia is one of the world’s largest producers of hydrocarbons, but it also stands to suffer from the melting of the permafrost in its north, which will turn huge areas into swamps. With the exception of its involvement in Russia-Ukraine talks on the transit of gas to the rest of Europe, the EU’s energy dialogue with Russia has been largely dormant since 2014; it should be revived. Russia and the West are both confronted with the risk that the coronavirus becomes a pandemic; there should be scope for their scientists to work together (and with Chinese experts). Russia and most Western countries face the social problems of low birth-rates and ageing populations, and immigration that is economically essential but unpopular: experts could exchange ideas on how to tackle these issues. In other words, the West should challenge hostile stereotypes propagated in Russian state media by showing its willingness to work with Russia wherever that is possible.

Western leaders should not forget history, ancient or recent, or ignore the reality of Putin’s Russia, but nor should they be its prisoners. The disappointed hopes of their predecessors may be buried all round the Kremlin; but the West’s relations with Russia do not always have to be as bad as they are now. As long as Putin’s guests have read their history books and come with realistic expectations, their visits need not end in tears.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform.

*Full disclosure: Pierre Vimont is a member of the advisory board of the CER.

Add new comment