The far right’s impact on the EU’s climate agenda

The far right is stronger than ever in the European Parliament. And climate policy has become a testing ground for its influence.

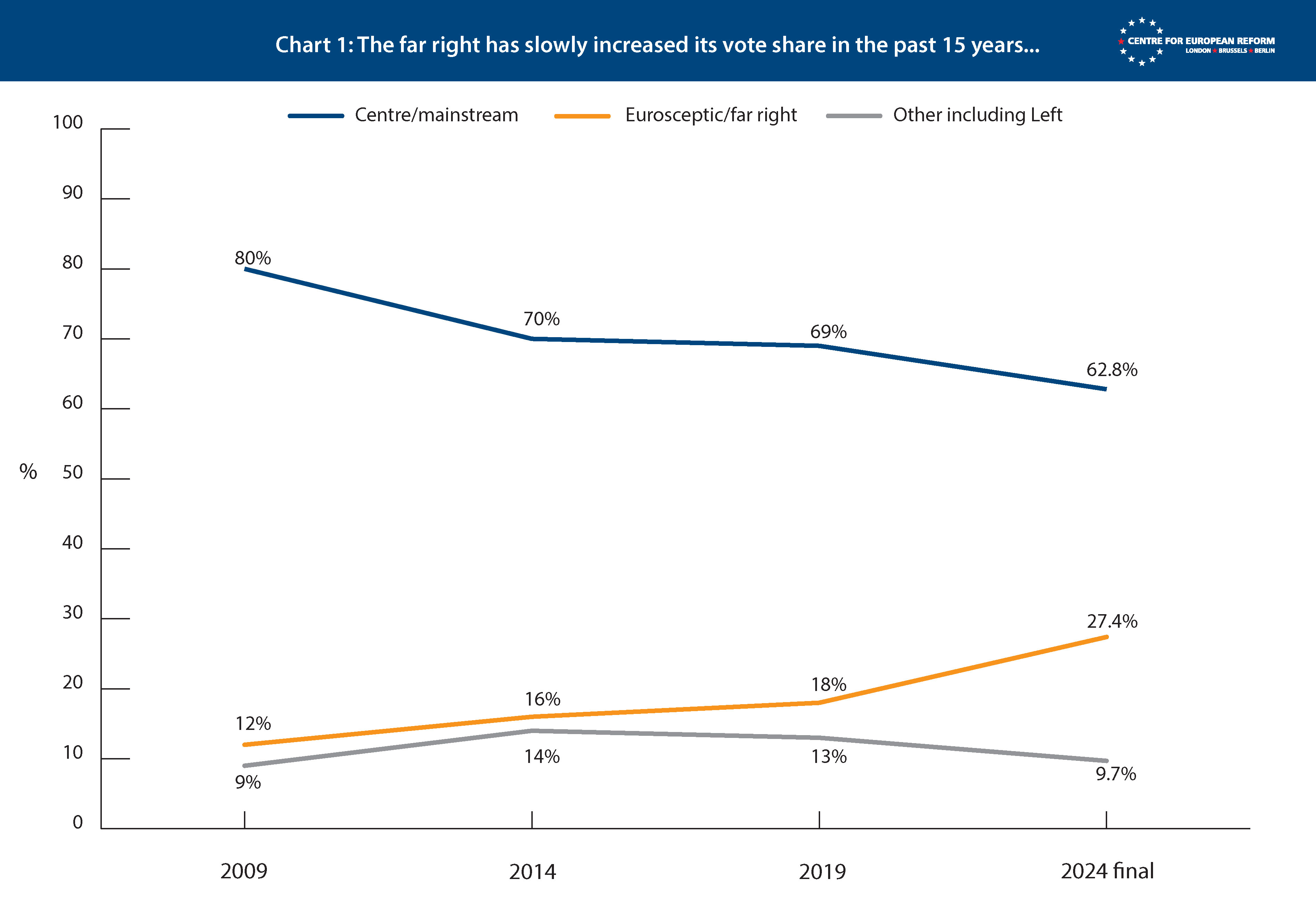

More than a year has passed since the far right made significant gains in the European Parliament (EP). The 2024 EP elections resulted in the highest-ever vote share for the far right: 27 per cent, or 191 seats out of the total 720, are now occupied by MEPs who belong to far-right party groupings.

This shift is both a reflection of the altered political landscape in Europe and a driver of further rearrangement. The fact that more than a quarter of the European Parliament aligns itself with far-right ideas demonstrates how much politics have changed at the member-state level. Radical right parties have topped polls in Europe’s four most populous countries (Germany, France, Italy and the UK); they are in office or support the government in seven (Belgium, Croatia, Finland, Italy, Hungary, Slovakia and Sweden); and have a significant impact on politics in eight more. This means that the far right influences the agenda in 17 countries, or more than half of the EU.

This hard-right shift is also affecting the policies of the centre. Moderate and conservative parties have started moving further right, changing positions on issues such as migration, civil society and climate.

To assess the policy impact of the far right in the new Parliament, this insight focuses on one specific area, the green agenda, because populist and far-right parties have recently benefitted from a political backlash against it at the polls (the so-called greenlash). It looks at both the direct impact, meaning the outcome of votes in the European Parliament, and any indirect impact, that is diluting or delaying existing legislation, hindering the adoption of new policies, or forcing centrist parties to shift away from supporting climate-friendly policies.

Hard numbers: Votes and outcomes in the European Parliament

There are different ways to define the far right and the terminology around it is not always clear-cut. Certain previously extremist parties have ‘moderated’ their rhetoric (such as Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia) and mainstream parties and groupings have moved to the right on several issues (such as the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) on migration). ‘Hard right’ and ‘radical right’ are also used to describe the same group of parties.

This insight uses Cas Mudde’s categorisation and the Populist 3.0 project to classify parties. According to Mudde, ‘far right’ is an umbrella term that includes the extreme right (parties that want to do away with democracy) as well as the radical right (parties that accept democracy but less so the rule of law, separation of powers, or minority rights). Using this classification, 89 per cent of two groupings, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the Patriots for Europe (PfE), and a 100 per cent of the Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) is comprised of far-right national parties. This insight therefore classifies all three groupings as far-right and adds six MEPs currently sitting in the non-attached group (NI), bringing the total number of far-right MEPs in the European Parliament to 197, or 27.4 per cent.

(A ‘stricter’ categorisation, that only includes 89 per cent of the ECR and Patriots, respectively, results in a total of 179 MEPs, or 24.9 per cent of the Parliament.) The three far-right party groupings, however, differ on numerous issues. The ECR is the most moderate; the Patriots – successors of Identity and Democracy (ID) from the previous Parliament and represented by France’s Marine Le Pen and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán – sit further to the right; and the ESN, the smallest grouping featuring Germany’s AfD, is the most hardline.

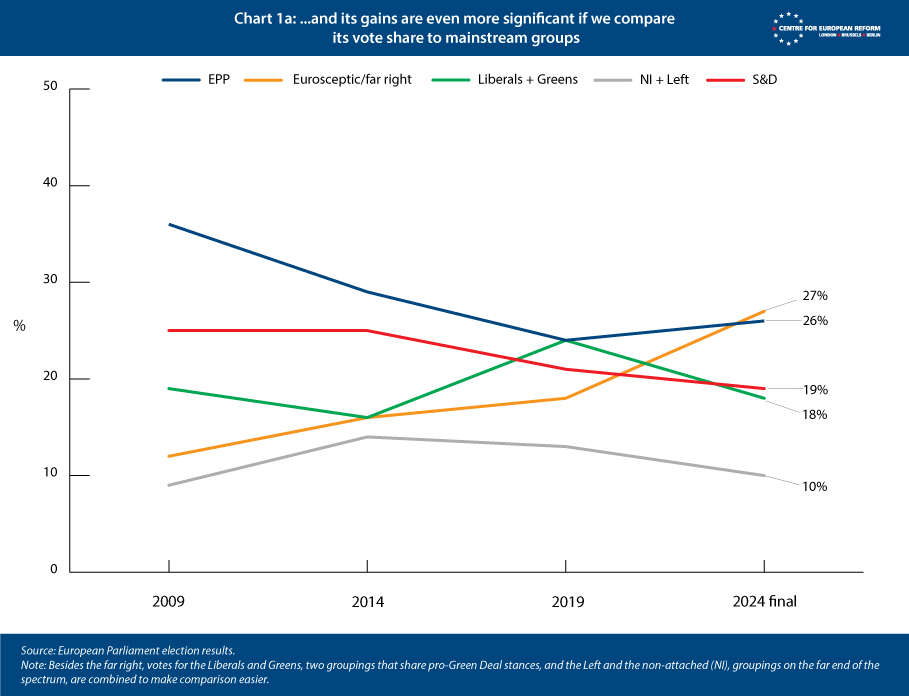

According to the numbers, therefore, the far-right threat is significant. Centrist and mainstream parties still dominate the European Parliament with 529 MEPs out of 720 or 63 per cent of the seats. But this percentage is the lowest ever the mainstream has achieved, and if we add together the seats of all far-right MEPs, they outnumber the two largest parties, the EPP at 26 per cent and the centre-left Socialist and Democrats (S&D) at 19 per cent (see Chart 1).

The far right now holds more than a quarter of the seats in the European Parliament. And its influence may be reshaping climate policies – and voting in the EP.

At the same time, the far right does not vote as a united bloc. Additionally, party discipline tends to be lower among far-right parties than in the mainstream, with MEPs following national interests or that of their domestic political party even when that means deviating from their group in the Parliament. In the previous legislative term, far-right groupings were the least cohesive, with their MEPs voting least uniformly (while the Greens were the most cohesive group). The lack of cohesion limited the far right’s policy impact in recent terms.

Given that the far right controls a much larger number of seats in this term, it has more potential to influence the policy debate, especially if far-right parties vote together. They also have more opportunity for impact with the EPP moving further right on certain issues. The ECR, the Patriots and the ESN have been divided on foreign policy, such as Russia’s war on Ukraine. But they have found alignment on climate policy since they all oppose the Green Deal.

The questions for this legislative term are therefore how united the far right can be, both internally and when it comes to co-operation between the three groupings, and how willing the EPP is to co-operate with it.

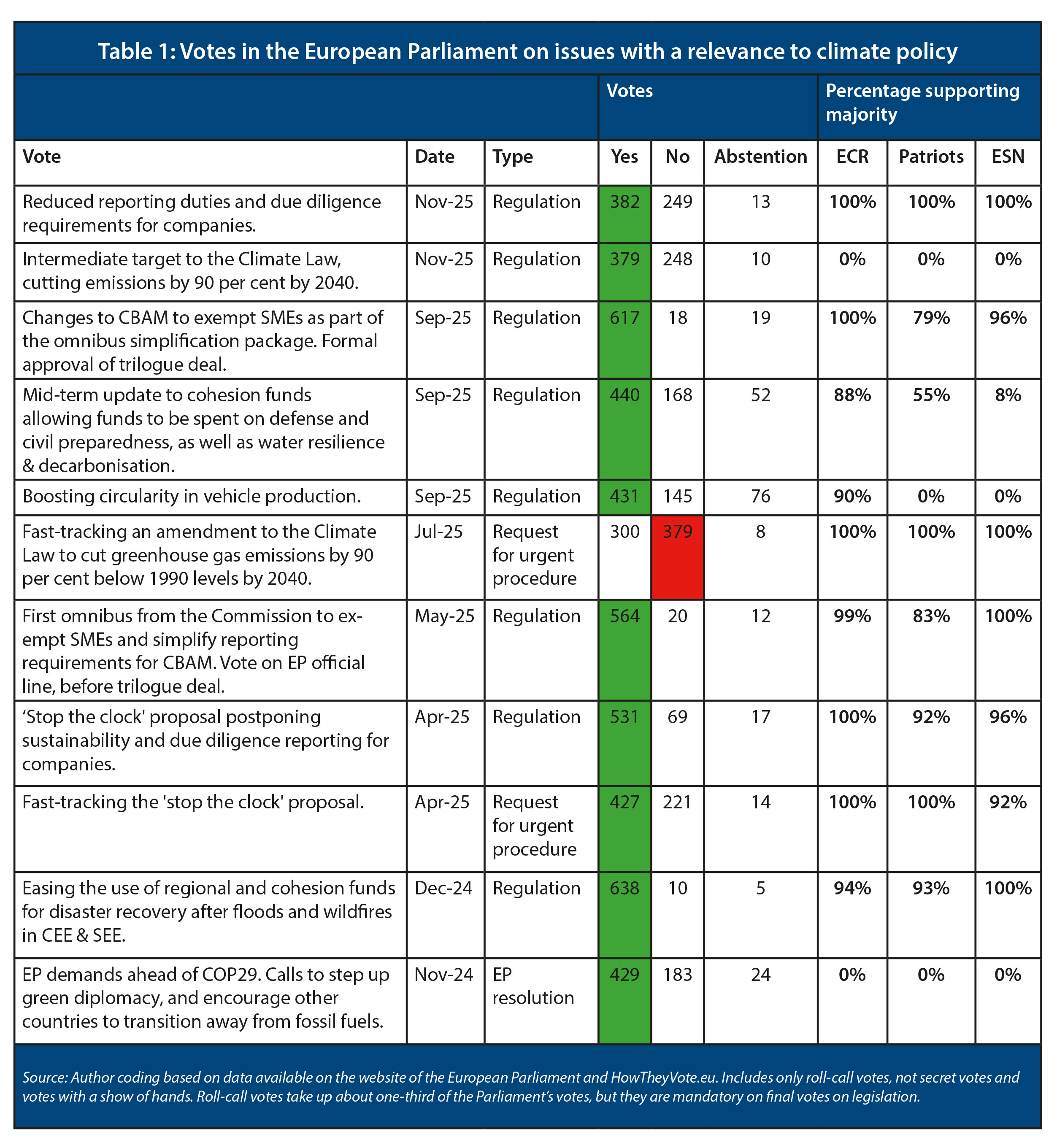

Looking at the votes on issues related to climate, a mixed picture emerges (Table 1). More than a year after the new Parliament started its work, 11 roll-call votes have taken place in plenary: eight of these were on regulations (on simplifying existing rules, setting an intermediate climate target, reallocating cohesion funds, and extending the life cycle of materials and products), one was a European Parliament resolution (on the EU’s position at COP29), and two were requests for urgent procedure (on the climate target and on the Commission’s ‘stop the clock’ proposal delaying sustainability and due diligence reporting requirements).

In most cases, far-right MEPs voted with the majority and there was relatively high cohesion among them. There were only two clear votes against the majority: a 2024 November EP resolution on COP29, which called for stepping up green diplomacy ahead of the Azerbaijan summit; and the 2040 climate target, which pledged to cut emissions by 90 per cent below 1990 levels and which was adopted in November 2025.

In two cases, the far right was divided. In the first case, in September the ECR voted in favour of boosting circularity, or extending the life cycle of materials in vehicle production, while the Patriots and the ESN all voted against it. The second case concerned the reallocation of some cohesion funds to other areas, including to water resilience and decarbonisation. Again, most ECR MEPs supported this, but the ESN almost uniformly opposed the change and the Patriots were divided. It is worth noting that this issue was only partially related to climate policy – the regulation’s main focus was defence and civil preparedness. The Greens, the most climate-friendly group, voted against the resolution, claiming that it served the interests of large defence contractors. Likewise, opposition to this regulation from the Patriots was not closely related to the green agenda – they were complaining that access to funds would be conditional on what they see as an “arbitrary basis” of respect for the rule of law.

The far right has often voted with the majority on climate. This, however, does not mean that it voted in favour of climate-friendly policies – rather the opposite.

Soft methods: Changing the policy discourse

Voting with the majority, however, did not mean that the far right voted in favour of climate-friendly policies – rather the opposite. There were two cases of ‘Venezuela majority’, where the EPP won a vote with the support of the far right. This was a new development; and one of these cases has the potential to significantly alter voting in the Parliament, and on climate policy, in the long run.

While in the previous term, most far-right MEPs remained on the sidelines – sometimes submitting copy-paste amendments and asking for the withdrawal of the EU’s climate laws – that has not been the case in the current term. In fact, the far right has been most active in the preparatory stage – before a vote takes place – achieving tangible, even if more indirect impact.

In July, the Patriots secured the file on the 2040 climate target and put in charge an MEP who had previously called it “utter madness”, recommending the withdrawal of the file as a whole. This was an important victory for the far right because rapporteurs are responsible for steering negotiations inside Parliament and can technically delay work on them. To prevent any delays, the S&D, Renew, and the Greens attempted to fast-track the law in July. But the EPP voted it down, arguing that there was no need for an urgent procedure. Since the vote was about procedure and not content, the EPP could maintain plausible deniability regarding a change in its support for the Green Deal. But the party’s intransigence was nevertheless significant as it made agreement on a climate target ahead of the November COP30 conference difficult.

There was still hope of an early completion when all four mainstream parties agreed on an accelerated timeline during the summer, with the aim of a plenary vote on October 1st. But the deadline came and went without any progress on the file. In the end, the Parliament waited for the Council to first reach an agreement and followed suit only in mid-November, after the start of the COP30 conference. The adopted file supported the original 90 per cent reduction in emissions by 2040 but allowed for flexibility to lessen costs on industry.

The far right in this case failed to derail the proposal, but watering down parts of the law could still endanger the EU’s climate ambitions. And while the target survived, the EPP itself was divided on the compromise, with 63 of its MEPs voting against it – and together with the far right.

The second vote, which focused on sustainability and due diligence reporting, was even more consequential. In this case, the S&D and Renew at first supported the EPP in seeking to ease reporting requirements. In fact, two votes on cutting red tape – exempting SMEs and simplifying reporting requirements under the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), a tariff on carbon-intensive products – had passed with large majorities earlier, in May and September, collecting support from all aisles. This showed that when the simplification agenda leaves previous commitments untouched (the CBAM will still apply to 99 per cent of emissions), it could enjoy broad backing. Large majorities had also supported a pause in the implementation of sustainability and due diligence reporting, the so-called stop the clock proposal.

But when it came to changing the rules of reporting, it transpired that there was no real agreement among the mainstream parties, and the S&D and Renew were amenable to co-operation only because the EPP had threatened to work with the far right. The EPP’s blackmail in the end backfired, leading to a last-minute upset in a secret vote in October, where some S&D MEPs voted against the compromise. They argued that the proposed changes – exempting companies from reporting on their environmental footprint and scrapping mandatory climate transition plans – would gut sustainability and abandon accountability.

This setback prompted the EPP to make good on its threat and, for the first time in the history of the Parliament, pass an important piece of legislation without its mainstream allies – and with the support of the far right. While 33 MEPs from Renew and the S&D also supported the simplification of rules, this new majority is bound to set a precedent for the future. For one, it could be the first step towards slowly diluting or even dismantling the Green Deal. And two, it could herald a new era with much less predictability and with alliances changing issue by issue in the Parliament. What happened on climate could happen on migration and even on the budget, opening the way for the far right to gain even more influence over an increasing number of policy areas.

Conclusion

More than a year in, the far right has had a negative impact on the green agenda and climate policy in the new European Parliament. While the mainstream continues to call the shots, the largest party, the EPP, has become more right-wing and less climate-friendly – thanks to the increased far-right presence. Far-right MEPs have primarily influenced the preparatory stage, slow-walking and diluting two important files. They have also enabled the EPP to promote its own policy priorities, simplification and deregulation, at the expense of the green agenda and transparency. Crucially, by voting with the far right, the EPP has opened the door to a more uncertain and less climate-friendly future.

More than a year in, the far right has had a negative impact on the green agenda and climate policy in the new European Parliament.

Ultimately, does the increased far-right presence in the Parliament matter? Yes and no. Yes, because the Parliament led on progressive policies in previous terms – from human rights to migration and climate – and with the mainstreaming of far-right ideas, this role may well change. But no, because the Parliament is a co-legislator, deciding together with the Commission and the member-states, which limits how much a far-right contingent in Parliament can achieve on its own.

What matters more for the green agenda is what happens within the mainstream and across the member-states. Several governments have concerns about the economic impact of climate policies and are pressuring the Commission for exemptions and tweaks. Indeed, just ahead of the October European Council summit, 19 member-states called for more simplification, opening the way to further changes and the watering down of climate policies.

This means the far right in the Parliament is a threat to the future of the climate agenda. But the bigger issue, both in terms of weakening existing laws and diluting future climate targets, may be the mainstream moving further to the right.

Zselyke Csaky is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment