The cost of Brexit to June 2019

The UK economy is 2.9 per cent smaller than it would be if the UK had voted to remain in the European Union, according to our latest estimate of the cost of Brexit to the end of the second quarter of 2019. The CER model also shows that the biggest victim of the Brexit vote has been business investment, while the weaker pound has failed to foster the big gains in exports that some Brexiters hoped for.

The basic aim of the CER’s cost of Brexit analysis is simple: to compare official UK data to a model that shows how the economy would have performed if Britain had stayed in the EU. We use data from other advanced economies to create a doppelgänger UK that did not vote to leave. An algorithm chooses – from a group of 22 advanced economies – a selection of those countries whose economic characteristics most closely matched those of the UK in the run-up to the Brexit referendum. The countries the algorithm chose were Germany (32 per cent of the doppelgänger), the US (28 per cent), Australia (17 per cent), Iceland (9 per cent), Greece (6 per cent), Luxembourg and New Zealand (4 per cent each). By comparing the UK’s performance to this construct, we can assess whether – and how – the Brexit referendum has hurt the British economy.

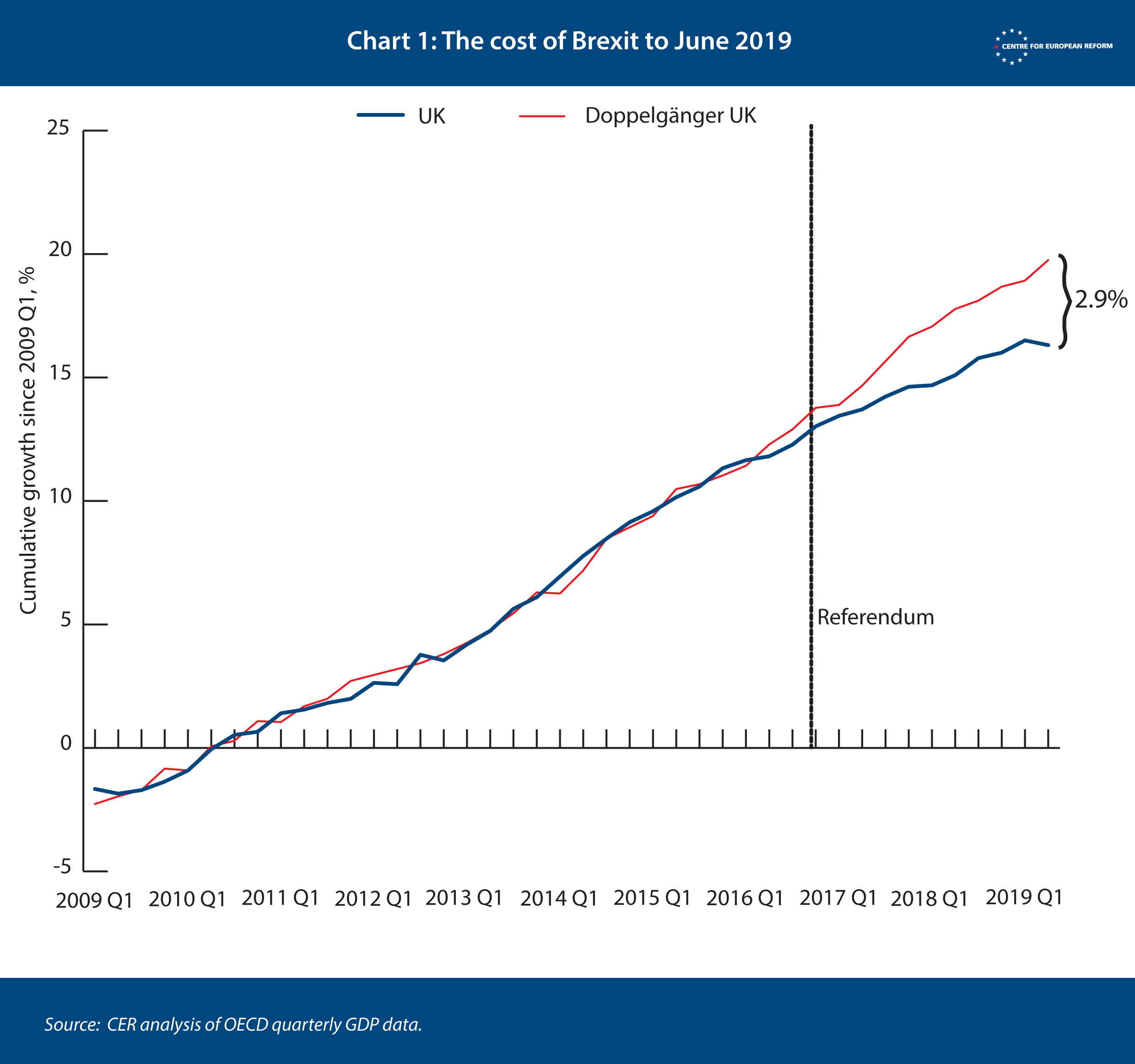

Chart 1 shows the diverging paths of the doppelgänger and the UK’s official economic data since the referendum. The gap opened up in 2017 and early 2018, when growth rates in most advanced economies accelerated. In usual times, the UK would have participated in such a growth spurt. Following that surge of growth outside Britain, the rate of expansion in the UK and the doppelgänger were similar in late 2018 and the first quarter of 2019. But the UK economy shrank in the second quarter of 2019 by 0.2 per cent, while the doppelgänger grew by 0.7 per cent, so the gap widened.

Some caution is required when interpreting these results. Quarterly GDP data is variable, and a weak quarter may be followed by an improvement in the next. In the second quarter of 2019, several OECD countries revised their past GDP data after improving the method behind their estimations (this is the reason why Germany has a higher weight – and the US and Luxembourg, lower – in our analysis this time round). And the degree of error in our model has also been growing over time as the economies of the various countries that form the doppelgänger are affected by factors unrelated to Brexit. One way to see this is shown in Chart 2. The US has been growing more strongly since 2018 than before, partly as a result of tax cuts that have raised the US government deficit. If we remove the US from the modelling exercise, so that it cannot be included in the doppelgänger, our estimate of the cost of Brexit falls to 2.2 per cent. Meanwhile, Germany’s large manufacturing sector has been hit by trade wars, dampening growth: while it did not do as poorly as the UK in the second quarter of 2019, its economy shrank by 0.1 per cent. If we exclude Germany, our estimate of the cost of Brexit rises to 3.4 per cent. Because of this rising degree of error, this will be the last update in the CER series on the cost of Brexit.

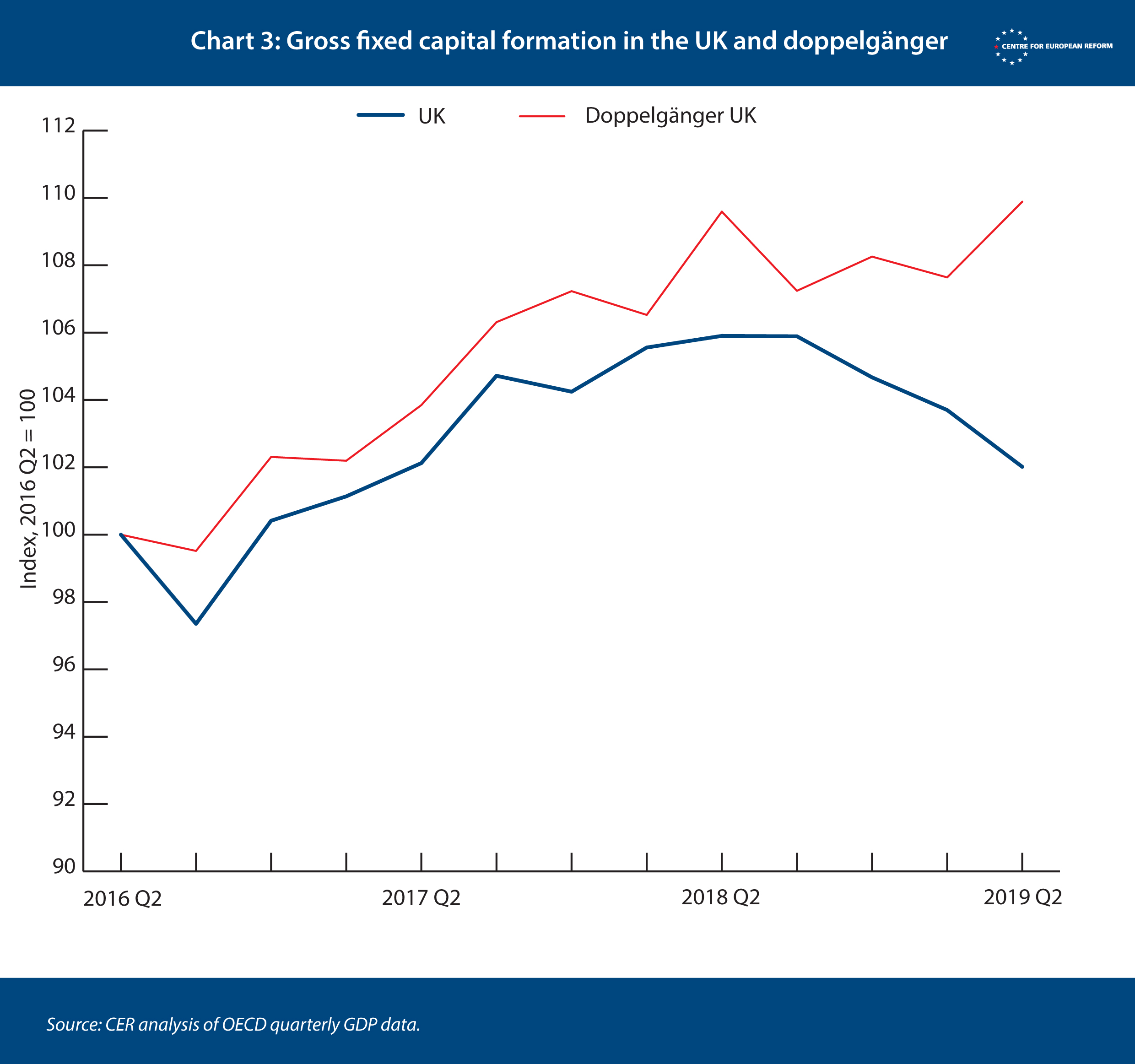

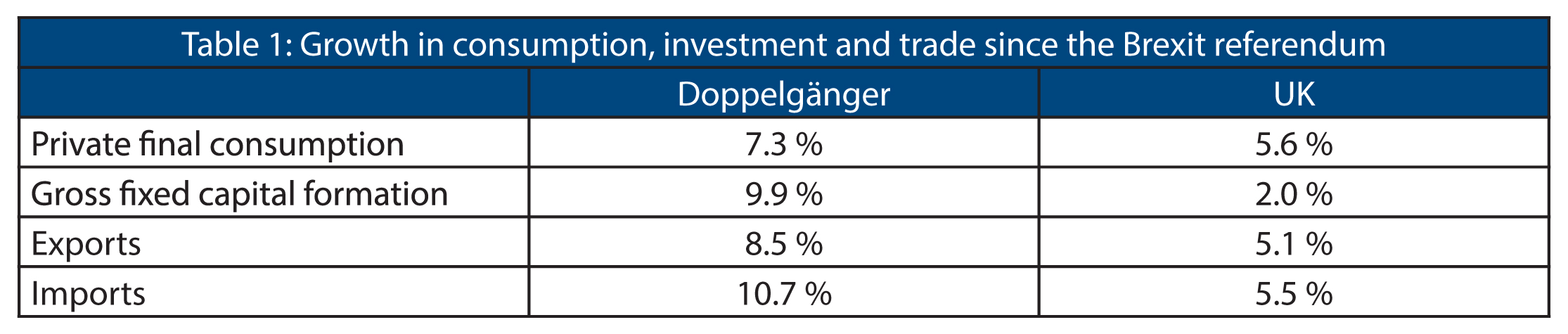

Looking back over the last three years, the biggest victim of the Brexit vote has been investment, which grew considerably less than that of the doppelgänger UK (see Chart 3). Gross fixed capital formation, which is new investment spending by businesses on capital goods, buildings, software and other assets, has risen by 9.9 per cent in the doppelgänger, and by only 2 per cent in the UK. Investment has been falling in the last three quarters in the UK, as businesses have been reducing capacity in the face of uncertainty about future demand for their products from both inside and outside the UK. Investment is an important driver of productivity growth – which has been woeful since the financial crisis in Britain, and which is the key determinant of rising living standards.

Consumption in doppelgänger UK has risen by 7.2 per cent since the second quarter of 2016, while it has only risen by 5.6 per cent in the UK. Consumption held up better than expected after the referendum, partly as a result of a decline in the household savings rate. But British consumers are probably spending less than they would have done if Britain had voted to remain.

And so far, the devaluation of sterling after the referendum has not yet led to trade rebalancing. UK exports grew more quickly than imports between 2016 and mid-2018, but the effect of the fall in sterling evaporated thereafter. And the UK economy has become slightly more closed to trade since the referendum, with both exports and imports lower than our doppelgänger, either because the UK economy has been growing more slowly, or because trade between Britain and the EU has already been hit by supply chains breaking up.

The next two weeks of negotiations in Brussels and political manoeuvrings in the British Parliament will determine whether the UK leaves with no deal, with a deal, or whether Brexit is delayed again. All credible forecasts of the cost of Brexit, if it finally happens, are that there will be a further hit to the UK economy, as barriers to trade, migration and investment are erected with Britain’s largest trade partner. But even before the UK has left the EU, the economic impact of the decision to leave has been large. So far, the main claim made by Brexiters in the referendum campaign – that Britain could regain sovereignty without damaging its economy – has proven to be false.

As usual, readers can find the source dataset here, the STATA code here and the results here.

John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment