In tech, the death of the Brussels effect is greatly exaggerated

The US and post-Brexit Britain want to carve out their own paths to regulating technologies like artificial intelligence. The EU, however, will continue to enjoy the most influence on global technology regulations.

The EU’s ability to project its own market standards across the globe is renowned. The Union may not be a military superpower. But the ‘Brussels effect’, to use the famous phrase coined by Anu Bradford of Columbia University, allows Europe to export its high standards globally. The Brussels effect protects European firms from being undercut by foreign competitors with lower standards. It also means the costs of high standards are passed onto consumers globally – not just those in Europe.

The Brussels effect is especially pronounced in the digital realm. Prompted by new EU ‘common charger’ rules, Apple is ditching its proprietary iPhone connector worldwide. And rather than developing separate processes for the EU, many of the world’s tech firms comply with at least parts of the EU’s landmark data protection law, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), everywhere. The jury is still out on whether other EU digital rules – such as on digital competition, platform accountability and the proposed law on artificial intelligence (AI) – will have global reach, however. In some of these areas, the US and UK are trying to forge their own approaches.

Some commentators already view the EU’s ability to project global norms as moribund. The Economist frequently suggests the EU’s digital laws are too onerous or too protectionist to be adopted worldwide and that Europe has too few tech giants to carry much influence. The Financial Times points to the EU’s shrinking share of the world economy as a sign that other countries may shun Europe’s regulations. If their premonitions come to pass, Europe could suffer dearly. Foreign businesses might delay the roll-out of their innovations in Europe and pass regulatory compliance costs onto European customers. The US and the UK would be freer to forge their own regulatory path.

But these warnings are too pessimistic. Sensible EU rules will perpetuate the Brussels effect – leaving the US and UK with little choice but to live with the EU’s global sway over tech regulations.

Is the EU’s shrinking share of the global economy a problem?

Detractors of the Brussels effect commonly point to the EU’s slow-growing economy and consumer base, and its lack of global tech firms. However, in cross-border trade, regulations are set not by the biggest economies but by the most important importers. The Brussels effect therefore requires that foreign tech firms see Europe as an “unavoidable trading destination”, as Bradford puts it.

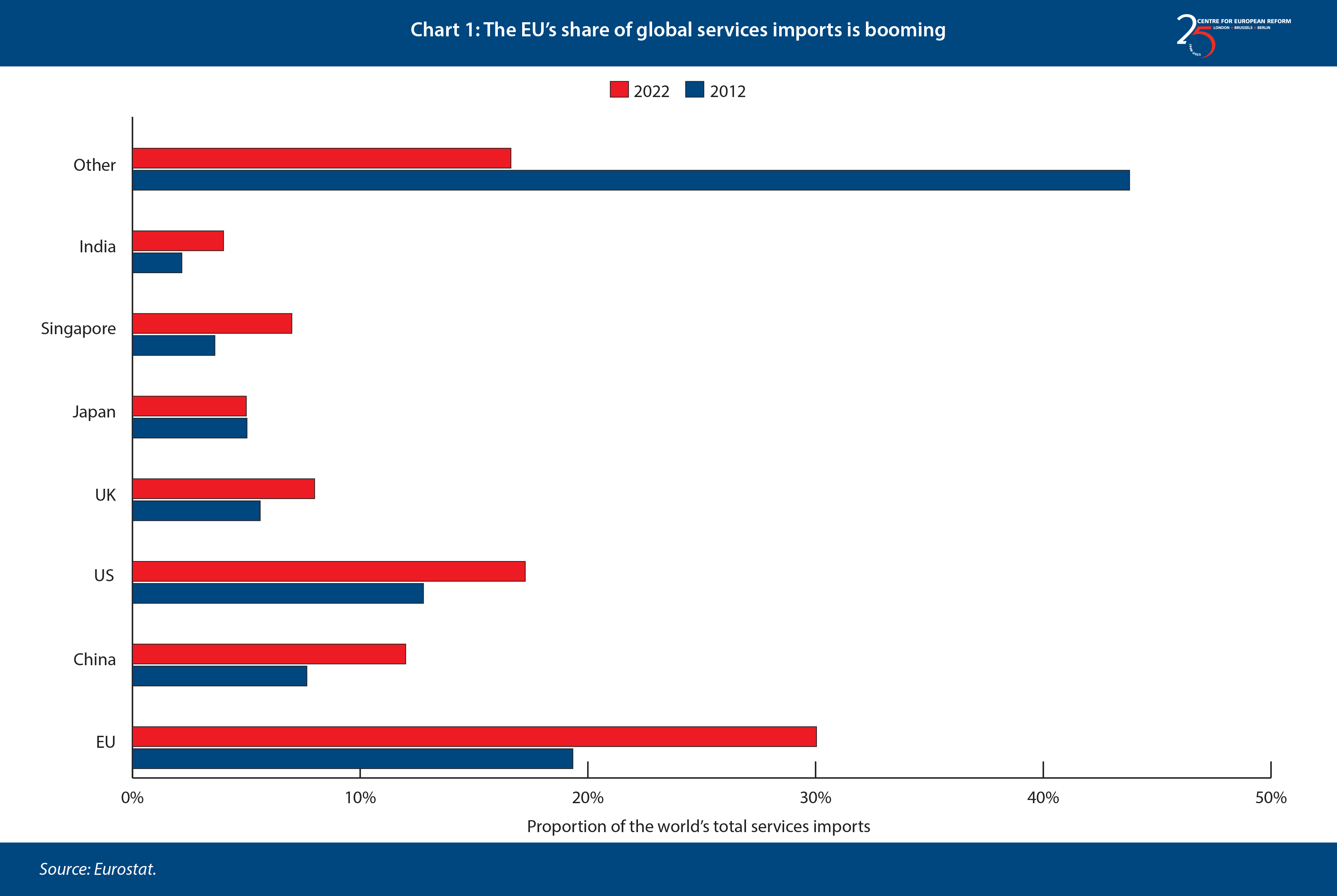

Because the digital economy is dominated by services – and EU digital regulations most commonly target how services are delivered, not how hardware is designed – the EU’s share of services imports is a useful starting point in assessing Europe’s regulatory influence in tech. As Chart 1 shows, Europe was already the world’s largest services importer in 2012, and its lead has only increased: it now attracts about 30 per cent of global service imports.

Recent research from the Jaques Delors Institute suggests the EU’s position as a services importer is particularly strong for digital services. But we can be even more specific when examining many digital regulations, because their biggest impact falls on a relatively small number of US tech firms. Ninety per cent of European data is managed by US firms, for example, and a lot of that business is concentrated in the largest firms such as the biggest cloud computing service providers. Meta and Apple obtain 22 per cent and 24 per cent of their revenue from Europe – second only to the US. Other large US tech firms do not isolate their European revenues in public reporting, but their published figures are consistent with Europe being their most important foreign market. This shows that the European market size will often be sufficient to offset the burden of costly regulatory compliance.

Furthermore, while many see the Brussels effect as being stronger in goods than services, digital service exporters may be more susceptible to the Brussels effect than goods exporters. If they see EU regulations as too onerous, goods producers can try to divert their products to alternative markets. Digital services providers do not have this option. They often have a global presence and it can be nearly costless to accrue new users – so leaving the EU market, or delaying the rollout of new services to Europe, represents a loss of revenue which cannot be mitigated. Tech firms that threaten to leave or to not rollout new services in Europe typically backtrack fairly quickly.

Are parallel services an option?

However, firms have another option to defy the Brussels effect. They may try to run separate parallel processes – complying with European standards only in Europe. This can sometimes be easier for services than for goods. Software can be tweaked to run differently in Europe. Goods manufacturers, on the other hand, have to invest in different physical production processes.

But whether segmentation is realistic depends on the service and the regulatory requirements. Parallel services could undermine the efficiency of running a unified global service, and splitting an existing service into an EU and non-EU variant can be technically complex. Think of social networks, which work by combining different individuals’ personal data – when one person comments on another’s post, both of their data must be linked. This makes it technically complex to isolate Europeans’ data and treat it differently. AI foundation models similarly benefit from more data and human feedback, making EU-only models undesirable.

Of course, in some cases, digital firms have nevertheless adopted EU-only approaches. The cost of compliance may be one reason. But two other factors seem equally important. One is that the EU has sometimes self-sabotaged the Brussels effect, by setting regulatory rules which cannot be applied globally – undermining so-called regulatory interoperability – or which undermine the EU’s role as a global importer. For example:

- National data protection authorities are applying the GDPR in ways that make it more and more difficult to transfer Europeans’ data offshore. This hard-line approach increasingly means global services firms must treat European personal data differently, even if the firm does its best to protect Europeans’ data held outside Europe.

- The EU is pursuing rules which could limit the use of foreign cloud computing services and hinder those services operating seamlessly worldwide.

- Even within the EU, there are risks of inconsistent or even incompatible laws. Member-states are increasingly being allowed to ‘gold-plate’ or ‘supplement’ the EU’s digital laws, for example. These pose the risk of breaking the Brussels effect from within the EU, forcing services to adopt different standards in certain member-states, and undermining the power of the single market.

The other case when digital firms might operate differently in Europe is where European rules deliver little meaningful benefit to consumers. Firms will face reputational risks if they give Europeans better services, but withhold those benefits from consumers elsewhere. But the reputational risk is reversed if EU laws hinder innovations or annoy consumers. Meta has not rolled out its competitor to X/Twitter, Threads, in the EU because upcoming digital competition laws might ban the way it uses data. Nor has Meta rolled out its paid GDPR-compliant version of Facebook and Instagram outside Europe. And while both Microsoft and Google rolled out changes to their products after EU antitrust action – Microsoft produced versions of Windows without Microsoft’s own media player or browser, and Google amended its listings for comparison shopping sites – the companies limited their compliance to the EU. In all these cases, EU regulations prevented the rollout of an innovation, or forced the rollout of changes which few consumers wanted. The EU should be careful to apply its digital competition rules and its Artificial Intelligence Act judiciously – since both risk annoying consumers and making it harder to rollout services consumers value.

Is EU law-making still a gold standard?

The Brussels effect is not just perpetuated by the private sector – foreign governments also model their own laws on EU regulations. Many countries – even, increasingly, the US – see a need for digital regulation in areas like competition, online safety, privacy and AI. They are turning away from what Bradford calls the US’s previous “techno-libertarian” approach.

The main reason why foreign governments adopt EU laws is because they are traditionally considered to be of high quality and tackle widely accepted problems. EU laws are negotiated between countries and institutions with different interests and legal systems. That means they often reflect sensible compromises.

Less-developed countries see the EU’s environmental laws as a form of ‘regulatory imperialism’ designed to disadvantage them. But most EU digital laws are typically based on well-accepted values like competition and fundamental rights. They are not broadly perceived to be attempts to boost particular EU countries’ economic interests.

European industry will not particularly benefit from EU digital competition laws, for example. Instead, the US and Britain have more start-ups which will comply with them in the European market if they become successful. The European Commission’s competition directorate, which will enforce some of these laws, has a reputation for defying attempts to use competition laws to pursue a European industrial strategy. And even laws limiting the use of foreign data and cloud providers – while they have clearly protectionist outcomes – are motivated, at least in part, by a genuine desire to limit the impact of US surveillance and therefore to protect Europeans’ data. But even if law-makers’ objectives are understandable, the perception of EU law-making becoming protectionist matters too. Brussels will need to ensure future regulation leaves the European market open if it wants other countries to keep seeing EU regulations as high-quality.

What does the enduring Brussels effect mean for the EU’s trading partners?

The EU is increasingly reliant on the Brussels effect to square its high regulatory standards with the need to maintain its attractiveness as a place for investment and jobs, and to prevent European consumers facing higher prices than consumers elsewhere. The EU’s regulatory influence in the tech sector should be relatively immune to Europe’s economic challenges, so long as EU regulations focus on benefiting consumers, keeping Europe’s markets open and not forcing firms into EU-specific business practices.

Europe’s propensity to regulate need not come at the cost of economic growth, either. Pro-competition regulations in the UK helped create huge numbers of start-ups. Similarly, stringent environmental regulations in Europe helped the bloc get a head start in green industries. The EU’s lack of big tech firms seems more attributable to the lack of capital ready to make risky investments, and the EU’s slow progress in deepening the single market.

This suggests even large economies like the US need to learn to live with the EU’s global sway and focus instead on influencing Europe’s regulatory approach. The US is trying to shape AI markets – both through the White House blessing US AI firms’ voluntary commitments, and by issuing an executive order setting standards for AI systems procured by the government. These commitments and rules remain weaker than Brussels’, however, and they are less enduring than laws. Donald Trump has already vowed to rip up Biden’s AI order. In the meantime, the primary forum for Washington to engage with the EU on tech regulation, the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC), has lost momentum. After failing to produce headline-grabbing outcomes, and broader EU-US relations facing challenges over a range of economic issues like the ongoing disputes about steel and aluminium, the US postponed the meeting scheduled for this month.

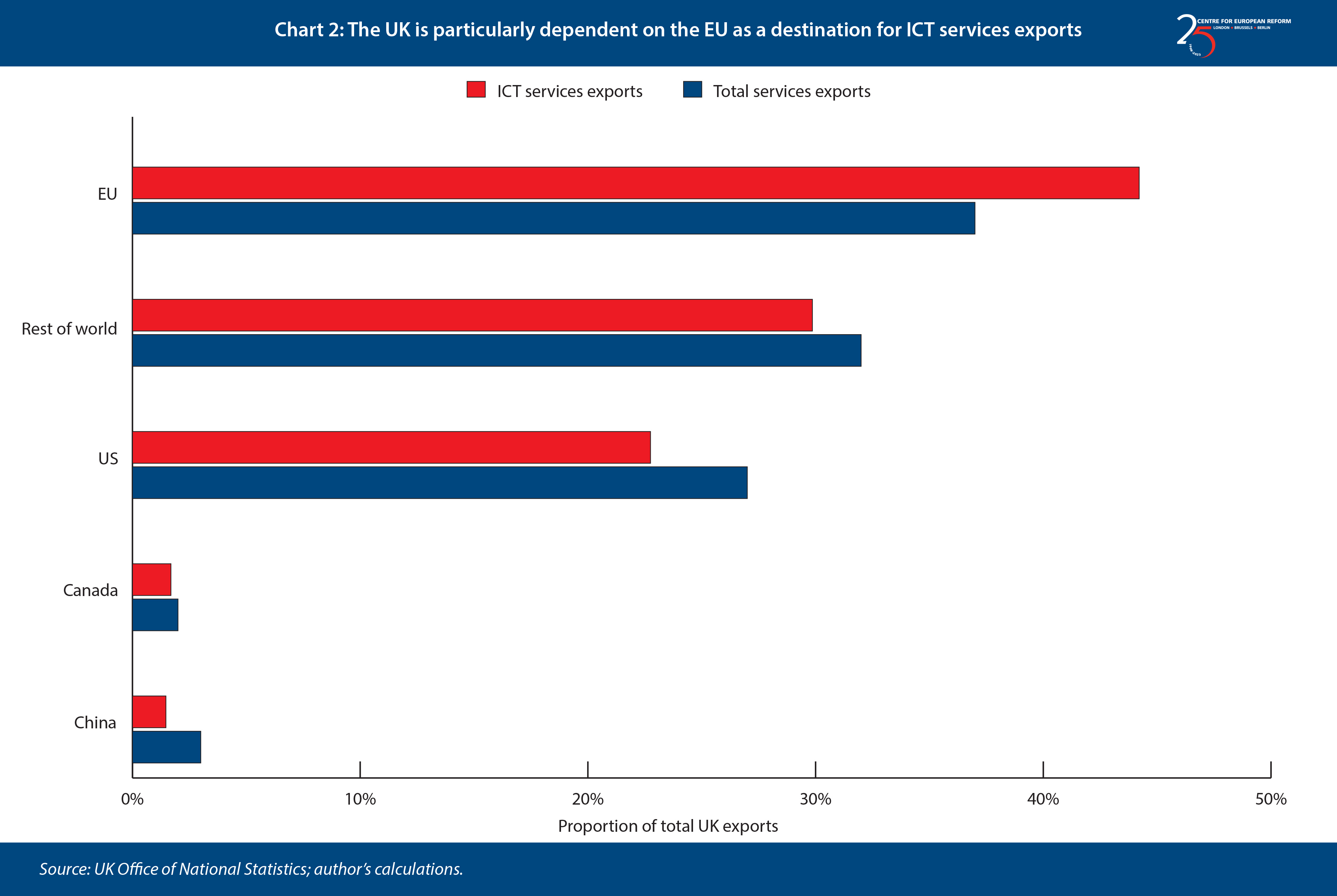

As for the UK, most economists think any ‘Brexit dividends’ will be found in the services sector, where geographic distance to trading partners might be less significant than for trade in goods. The persistence of the Brussels effect in the digital sector, however, raises questions about whether the UK will benefit from lighter-touch tech regulation.

As Chart 2 shows, the EU remains far more important to the UK as a services export destination than any other market, and that dependency is particularly acute for ICT services exports.

That explains why the UK has acted carefully. On the one hand, the government has proudly announced a more agile and lighter-touch approach to tech regulation. Yet the UK has been equally careful to avoid incompatibility with EU rules. The ambitions of its data protection reforms have been curtailed, to avoid putting seamless data transfers with the EU at risk. Its digital competition laws may give the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) more flexibility than the EU’s similar rules – but they allow the CMA to largely replicate the EU’s approach. The CMA emerged bruised from taking a tougher approach than Brussels to Microsoft’s recent acquisition of Activision – which suggests that largely following the EU may seem more sensible.

The UK currently has little formal ability to influence EU digital law-making. While EU-UK relations have improved under Rishi Sunak, the EU remains uninterested in the creation of a UK-EU TTC and the European Commission has been only haphazardly willing to engage with UK regulators. A future Labour government might help unlock closer co-ordination on tech regulation, which would be far more useful to the UK than continuing to trumpet relatively minor regulatory divergences from the EU.

The EU’s enduring ability to set global tech standards leaves the US and the UK with little choice but to accept that their tech firms will have to live with EU rules. Rather than trying to extract opportunities from lighter-touch approaches, the US and UK would be better off engaging with the EU to help moderate its regulatory excesses.

Zach Meyers is assistant director of the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment