Why the EU's recovery fund should be permanent: Country report - France

COVID-19

France has had one of the highest rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the EU, after three large waves in March and October 2020, and in the spring of 2021. Like most European countries, France provided a ‘chômage partiel’ furlough scheme for workers in businesses that were forced to close or limit operations during the pandemic, in effect socialising the worst of the pandemic’s economic costs.

Due to that sizeable third wave, in April the Banque de France cut its growth forecast for 2021 from 6 per cent to 5 per cent. With the French economy shrinking by 8 per cent in 2020, this means that it is unlikely to recover its pre-pandemic level until mid-2022.1

France’s vaccine rollout has been rapid. Despite the EU’s mis-steps with procurement, and early polls showing fewer than half of French people would take the vaccine, vaccine uptake has steadily improved, especially after the government made vaccine passports mandatory to enter bars and restaurants.2 Nonetheless, the delta variant’s infectiousness means that very high levels of vaccine coverage may be needed to prevent a resurgence of the virus in the winter of 2021-22.

Long-term economic performance

France went into the pandemic with a reasonably balanced current account, and a low public deficit, and it has had little trouble financing the big jump in its deficit as a result of its pandemic-related spending. While it has high productivity levels – similar to northern Europe and the US – France has struggled with low productivity growth since 2008, with GDP per hour worked growing by 0.5 per cent a year on average. Like many advanced economies, some combination of the freeze in the banking system, tight monetary policy, tight fiscal policy, a reduction in the rate of productivity-enhancing innovation, and falling expectations by investors about future demand meant that growth has disappointed.

In the fourth quarter of 2019, France’s unemployment rate was high, at 8.5 per cent, which is a little lower than President Macron believes its ‘structural’ unemployment rate to be.3 France imposes high tax rates on employers, including taxes on value added and higher social contributions once firms have hired a certain number of employees. It has fairly strict worker protections, and relatively generous unemployment benefits. As a result, France has a higher rate of unemployment than many other countries.

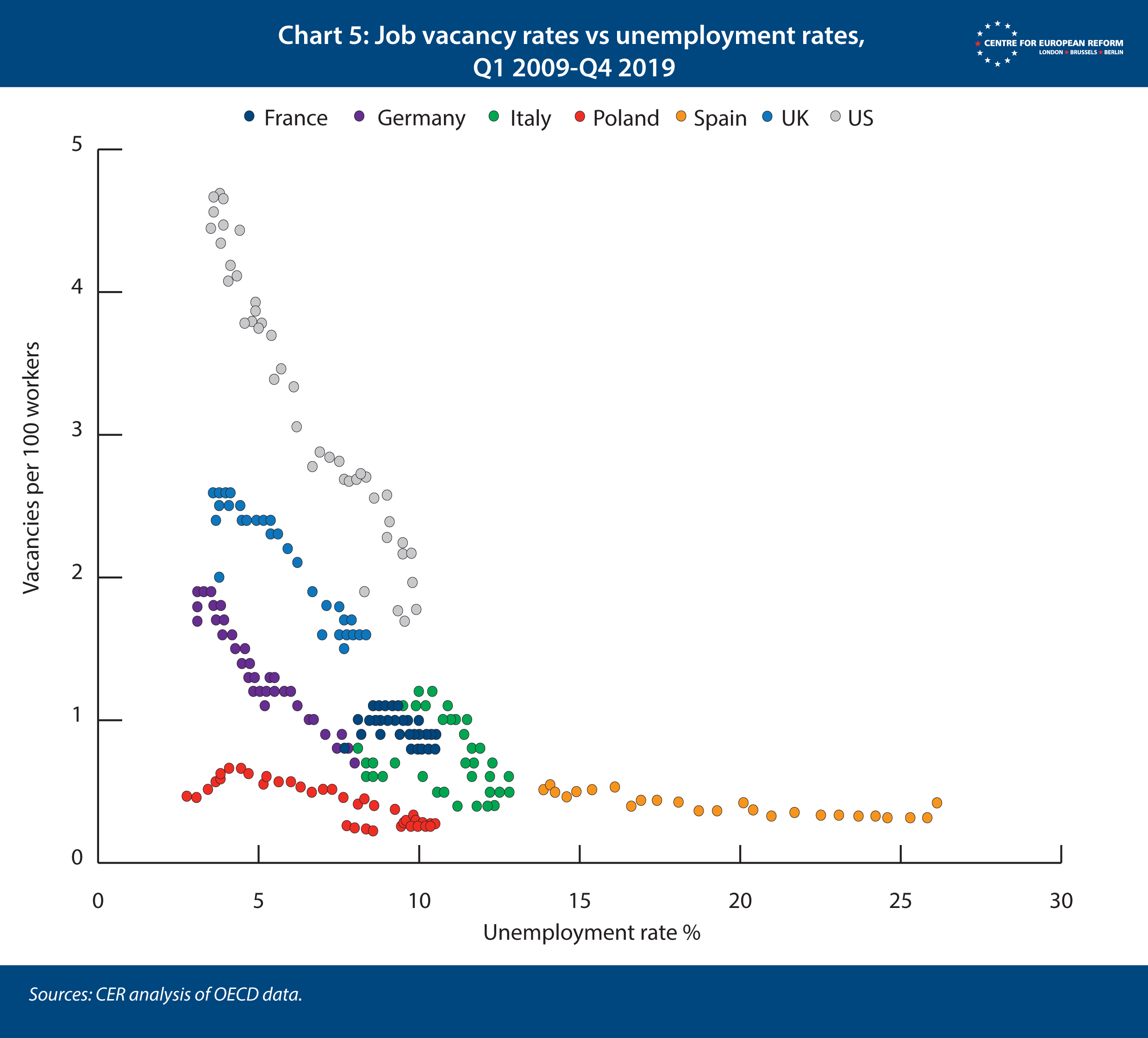

However, it is not yet clear whether France will suffer from a long period of higher-than-usual unemployment as a result of the pandemic. Thanks to its furlough and short-time work scheme, as well as the reopening of the economy after lockdown, in August 2021 unemployment stood at 8 per cent – lower than its pre-pandemic rate (which had been its lowest rate for over a decade). But as the furlough scheme is unwound, France’s relatively static labour market is a source of potential weakness. Over the 2010s, France’s businesses created new jobs more slowly than those in Germany and the UK. Chart 5 plots the vacancy rate (how many jobs are advertised as a share of the total labour force) against the unemployment rate. Germany and the UK create more new jobs, which (in combination with less generous job protections and unemployment insurance) lead to more people working.

This relative lack of dynamism in the labour market meant that France was slower to recover its pre-2008 employment rate than Germany, Poland or the UK: it took until 2017 to do so (Chart 6). With more static labour markets, it takes time for shocks to particular sectors of the economy to lead to workers moving to other roles.

Greenhouse gas emissions

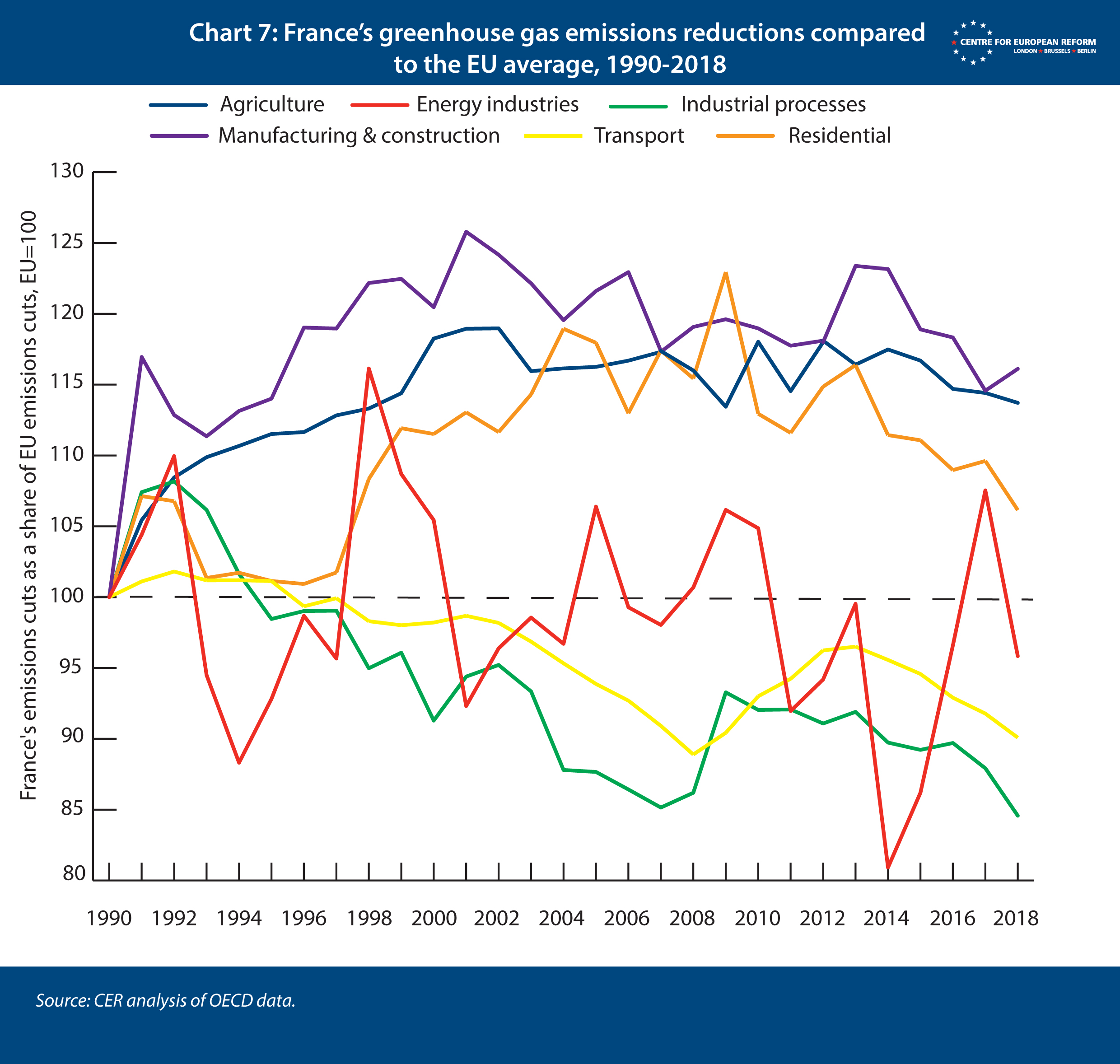

By 2018, France’s overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions had fallen by 18 per cent on 1990 levels, less than the EU average of 26 per cent. But France’s emissions have been comparatively low for decades, with more than 70 per cent of its electricity coming from nuclear. As a result it has fewer less costly ways to reduce emissions, such as closing coal and gas-fired plants. Chart 7 shows how rapidly France has cut emissions from six sectors of the economy compared to the average pace of cuts in the EU (the dotted line on the chart). It has managed to reduce emissions slightly faster than the EU average in transport and industrial processes (such as chemicals, cement, steel and so forth). But it has performed far more poorly in manufacturing, construction, housing and agriculture than the EU average.

The High Council for Climate (HCC), the government’s independent climate watchdog, found that the government had missed its 2015 and 2018 targets for housing, transport and agriculture. These sectors are an important focus of France’s plans for investment in 2021 and 2022, under its France Relance (‘France Relaunch’) programme.

France’s recovery plan

The France Relance plan was published in September 2020. €100 billion will be spent over several years, with €40 billion provided by grants from the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility. In the document, the government pointed out that France’s productivity growth had been poor, so the country needed to improve the use of digital tools by businesses (particularly SMEs), raise the dynamism of the labour market and find better matches between employers and the skills French workers possess. And it argued that faster economic growth was needed to make public finances sustainable, implying that government investment would reduce debt ratios by increasing tax revenues.

The France Relance plan amounts to 4 per cent of GDP, with the spending spread out over several years (although the French government plans to meet all spending commitments by the end of 2022). That is a macroeconomically significant sum, which will appreciably raise France’s growth rate.

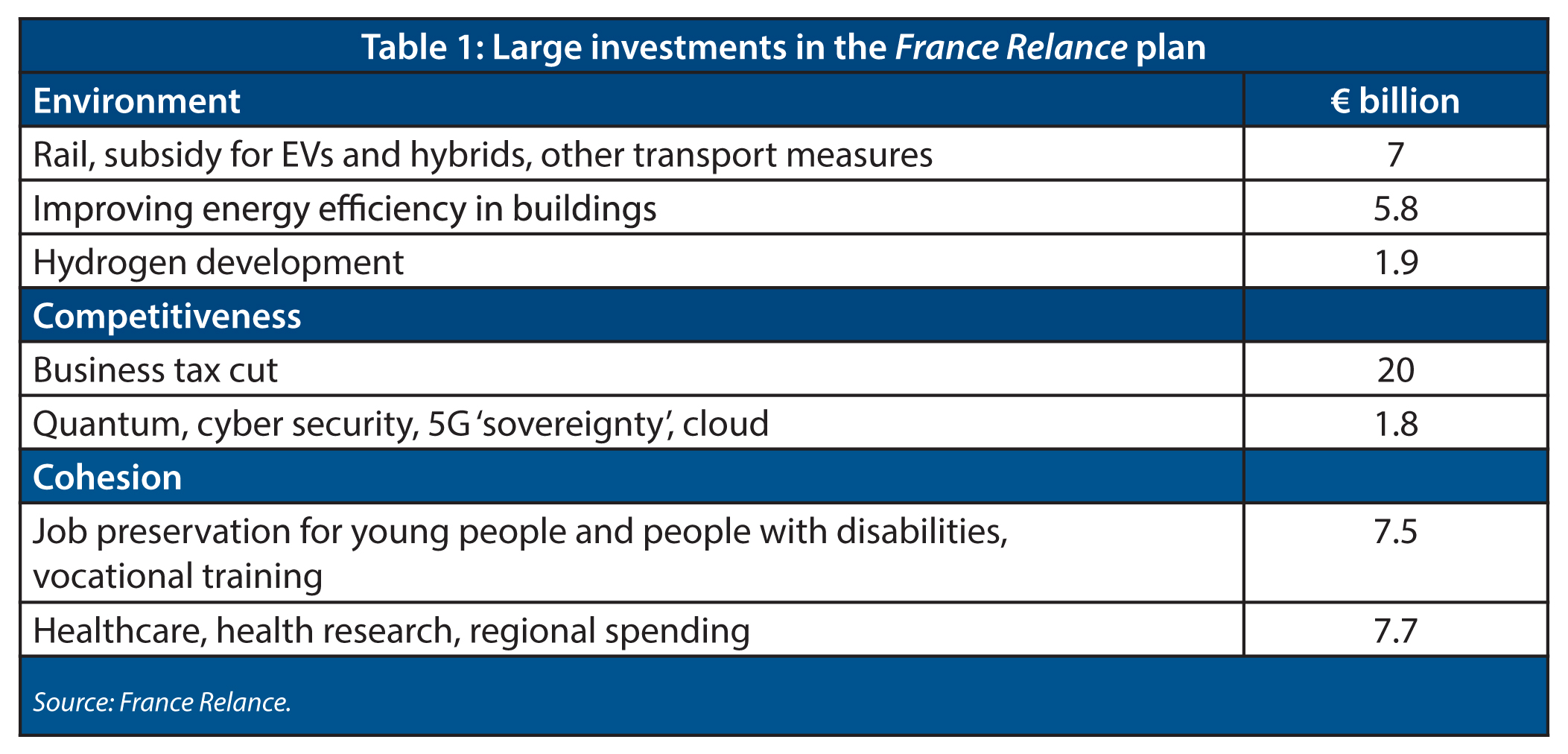

The plan is under three headings: €30 billion will go towards green investment; €34 billion will be spent on reducing taxes on business, on investment in digital technology and skills; and €36 billion will be spent on regional and social cohesion. Some of the larger spending lines are shown in Table 1.

France will spend a little more than Germany on subsidies for electric and hybrid cars – €1.9 billion vs €1.1 billion – and will provide the state railway company, SNCF, with €4.7 billion for maintenance and upgrades. But it is spending far more than Germany on improving the energy efficiency of buildings - €5.8 billion vs €2.5 billion – a sensible policy, because carbon emissions from housing were higher in 2018 than they had been in 1990. That money will largely be spent on subsidies for poorer people to help cover the cost of retrofitting their accommodation, as well as improving energy efficiency in public buildings. France will also introduce tougher energy standards for new buildings in 2021.

France and Germany are leading an EU ‘project of common interest’ on hydrogen, which they hope will provide an alternative fuel for heating and trucks, which may be hard to electrify. But the amount that France is committing is far smaller, at €1.9 billion, than Germany’s €10.5 billion. It is hard to appraise whether Germany’s bet will pay off, but economists largely agree that the most efficient way to develop new climate technology is for governments to impose prices on carbon, or find other ways to restrict emissions, and allow markets to finance new innovations and diffuse them across the economy. While early stage scientific projects, especially at scale, might be so risky for private investors that they are undersupplied by market forces, there is also the risk that hydrogen fails to become a cheap, green fuel, since it needs a lot of electricity to create it..

In its investments in digital technology, the French government is making some risky bets, especially because innovation in this sector is already dominated by US companies. France plans to invest €1.8 billion in quantum computing, cybersecurity, better digital education, 5G ‘sovereignty’, and cloud computing. Most of that money will be awarded competitively to early-stage projects, with the aim of creating jobs in these areas and creating a cadre of skilled tech engineers and entrepreneurs. While US government investment has been important to the development of its tech sector, especially through defence spending, its large venture capital and consumer market and rich, privately funded universities are also important. Europe has also struggled to reduce trade barriers to digital services within the single market, and its universities are largely funded by the taxpayer, not tuition fees and donations.

As part of a range of changes to corporate taxation, including a reduction in the headline rate, France will also cut taxes on investment. France is unusual in that its companies must pay tax on the value of their assets, irrespective of their profit and loss position, which discourages investment. The rate of tax on business rents will be reduced, as will a tax on corporate value-added on companies with a turnover greater than €152,000. This will result in a €20 billion reduction in the tax take from business by the end of 2022. These taxes are highly distortionary, in that they discourage businesses from expanding and renting larger properties. These tax cuts could lead to higher investment across the economy (as long as businesses are convinced that future aggregate demand will be robust).

France plans to spend €7.5 billion on job schemes and vocational education and training, which will largely flow to young people, especially those who are ‘farthest from employment’. It is not yet clear how quickly the labour market will recover, and younger, poorly educated people always suffer most during recessions and their aftermath, as they have the fewest marketable skills.

In sum, the plan makes a good deal of sense, as it focuses on some of France’s more long-standing problems as well as the particular problems thrown up by the pandemic. The plan promotes social cohesion by targeting subsidies for energy efficiency, training and job protection towards poorer people. But the effects of the plan on carbon emissions will be modest: the government, to its credit, has estimated that the plan will reduce emissions on a cumulative basis by 1 per cent by 2030. That is not nothing, but further emissions reduction will require more unpopular policy choices to be made this decade, especially in France’s more problematic sectors: transport, buildings and agriculture.

2: ‘Covid-19: Les français ont de plus en plus confiance dans la vaccination’, Le Monde, May 21st 2021.

3: ‘Macron says French structural unemployment rate of 9 per cent is scandalous’, Bloomberg, February 13th 2018.

Elisabetta Cornago is a research fellow and John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform

November 2021

This paper is published in partnership with the Open Society European Policy Institute.

View press release

Download full publication