Why the EU's recovery fund should be permanent: Country report - Portugal

The impact of the pandemic on Portugal

Deaths have been close to the EU average, at around 1,700 per million.1 Portugal locked down promptly in the first wave of the pandemic, but the country suffered further waves, with the peak of the pandemic coming in early February 2021, with over 200 people dying per day.

However, the vaccine rollout has been good, with over 85 per cent of the population having received at least one dose of the vaccine by early October.2 The infectiousness of the Delta variant means that the country could still be susceptible to another wave, but by early October cases had declined to 500 a day.

The importance of tourism to Portugal’s economy meant that its economy was one of the worst performers in the EU in 2020, shrinking by 7.6 per cent. It shrank a further 3 per cent during the strict lockdown of the first quarter of 2021. As with most other countries, government wage subsidies meant that the unemployment rate did not rise markedly, and a fairly rapid recovery is likely, despite the reduced tourist numbers in the summer of 2021. However, the European Commission forecasts that the country will only reach its pre-pandemic level of output in mid-2022.

Long-term economic performance

Portugal’s economy shrank for two years after the 2010 eurozone crisis. After 2012, growth was weak until it accelerated to around 2.5 per cent a year from 2016 to the end of 2019. Portugal’s centre-left government had relaxed austerity measures when taking office in 2015, and a pick-up in growth in Spain and the rest of Europe boosted exports. The country’s relatively high debt, which peaked at 133 per cent of GDP in 2014, had fallen to 118 per cent in 2019, before the pandemic pushed it back up to 133 per cent in 2020.

There are two main economic risks facing Portugal: one cyclical and one structural. Before the pandemic, Portugal’s services exports, led by travel and tourism, had improved markedly, benefitting from investment in higher-value tourism.3 With luck, tourism revenues will not be permanently lower in the future, as COVID-19 becomes less lethal; but the virus may reduce tourist numbers for several years, which would mean that other sources of export revenue may need to be found.

The second, more structural problem is that Portugal has long-standing weaknesses in skills and gender equality. Portugal has one of the highest shares of less educated workers in the EU – in 2018, 57 per cent of the workforce had low qualifications, compared to the EU average of 20 per cent.4 But the gap is smaller among younger workers – which may suggest that recent investment in education and skills is paying off. Women are over-represented in temporary, part-time and low-skilled jobs, which is why the country has a higher gender pay gap than the EU average. Raising public investment in childcare provision and reducing the very high level of protection for workers with permanent contracts, who are largely men, would help to reduce these disparities.

Greenhouse gas emissions

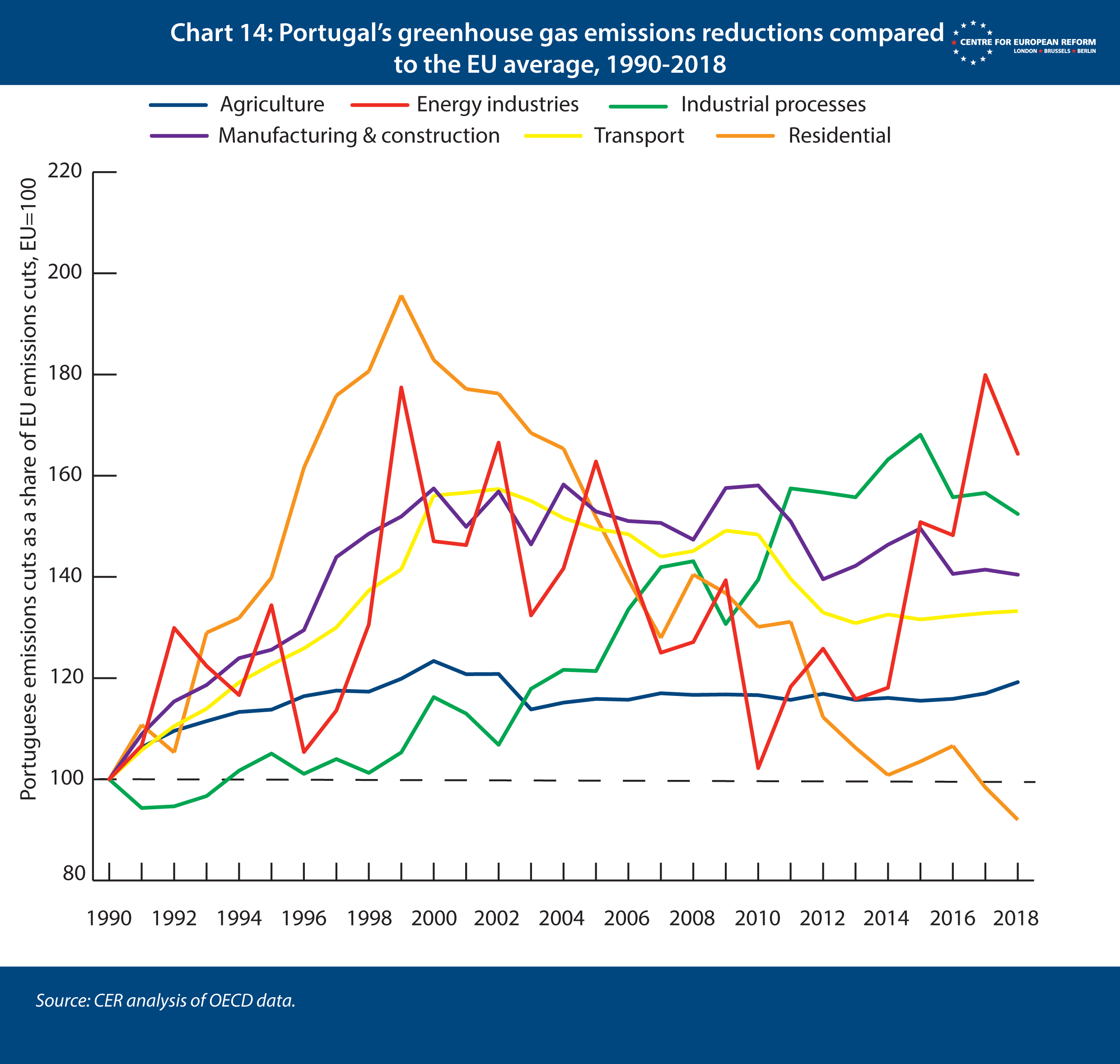

Portugal easily achieved its unambitious 2020 target of a 1 per cent increase in GHG emissions compared to 2005 levels. By 2019 they were down by a fifth. Chart 14 shows Portugal’s emissions cuts in proportion to the EU average (shown as 100 on the chart). In all sectors bar emissions from residential buildings, its cuts to emissions were smaller than the EU average. As one of the poorer countries in Western Europe, that is perhaps not surprising. But Portugal’s GDP in 2014 had fallen back to its 2000 level, thanks to the euro crisis, and had its economic performance been better its emissions performance would have been far worse.

Portugal’s 2030 targets are much tougher – they require a cut in emissions of 45-55 per cent on 2005 levels. This means that Portugal will have to cut emissions by a further 30 per cent on 1990 levels by the end of the decade, with a 17 per cent reduction coming from sectors that are not covered by the ETS, such as transport and buildings. Luckily, Portugal has some of the best conditions for renewables in Europe, being a sunny and windy country, which will help it meet its testing 80 per cent target for renewables’ share in electricity generation, and 47 per cent for final energy demand.5 Portugal also plans a 35 per cent cut in energy consumption on 2005 levels.

Portugal’s recovery plan

Portugal is seeking a total of €16.6 billion from the EU, with almost €14 billion coming in grants and €2.7 billion in loans. The government will decide whether to take up a further €2.3 billion in loans in 2022, if demand for one of the measures it plans to use the loans for – the capitalisation of businesses and support for business R&D – is strong enough. Portugal has set up a national R&D bank, the Banco Português de Fomento, which is taking equity stakes in companies that it deems to have growth potential but that have been battered by the pandemic.

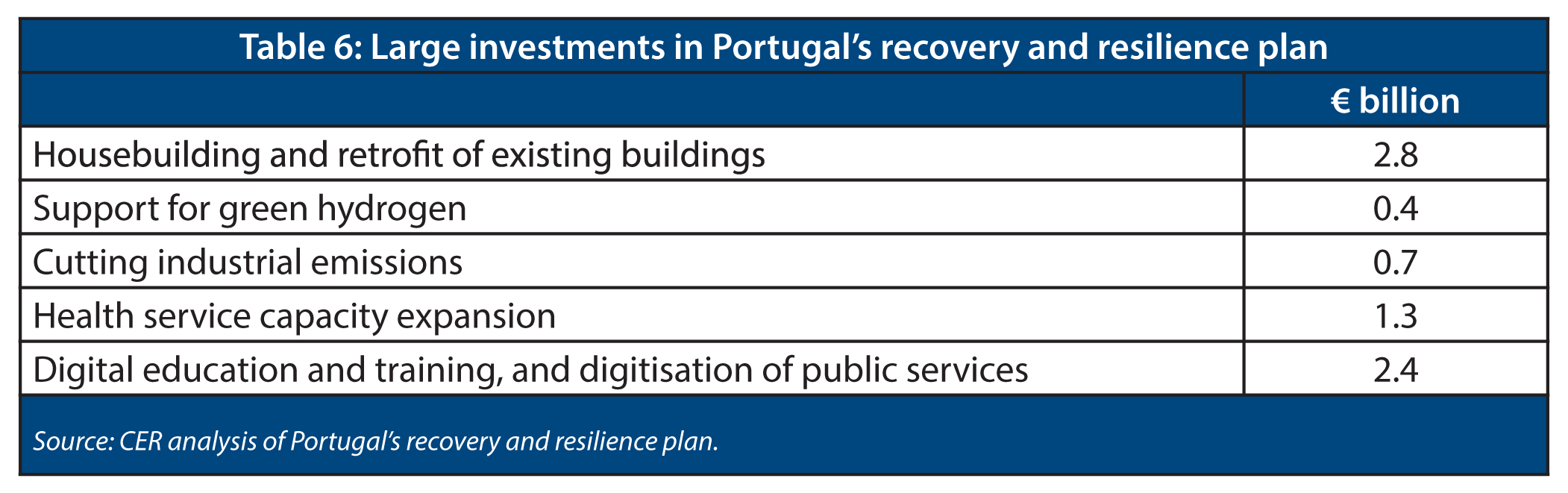

The main elements of the plan are fivefold. First, the government plans to expand the national health service, which had too few hospital beds to cope with the pandemic. It plans to spend €1.3 billion on 6,000 new hospital beds and 34 mobile units providing primary care in rural areas. And it will expand the provision of care services for children, the elderly and disabled people.

Second, Portugal plans to spend €2.8 billion on building projects –better housing for 26,000 households and support for the renovation of public and private buildings (including €610 million to be spent on improving energy efficiency in buildings).

Third, it will spend a further €2.7 billion on climate and environmental policy, including €715 million on decarbonising industry, €370 million on R&D in renewable hydrogen energy (which the country’s abundant renewable resources should help with), and €1 billion on public transport and rail infrastructure.

Fourth, as with many other countries, it will spend a significant sum on digitisation (€2.4 billion) and, sensibly, given its high share of low-skilled jobs, on education and training (€1.3 billion). Some of the digital investments – in improving access to public services, and digitising the records of the national health service, and the provision of justice and tax collection – are similar to other countries. The government will also upgrade science facilities in schools and universities. A large sum – €650 million – will be spent on training in small and medium-sized businesses to improve their use of digital technology.

Fifth, Portugal will seek to reduce barriers to entry into regulated professions and make it easier for firms to hire people on permanent contracts. An equal pay act and other laws will strengthen employment rights for women.

2: ‘Share of people vaccinated against COVID-19’, Our World in Data, October 4th 2021.

3: ‘2019 Article IV consultation, Portugal, ‘, IMF, July 2019.

4: ‘2020 skills forecast: Portugal’, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, 2020.

5: ‘Europe 2020 targets: Statistics and indicators for Portugal’, European Commission, 2020.

Elisabetta Cornago is a research fellow and John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform

November 2021

This paper is published in partnership with the Open Society European Policy Institute.

View press release

Download full publication